This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

How to become an instant expert on... Tutankhamun, the boy Pharaoh behind the tomb

How to become an instant expert on... Tutankhamun, the boy Pharaoh behind the tomb

20 Sep 2022

This year marks a milestone in the history of Egyptology: the centenary of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb. The world was agog for its discovery and treasures, but the young king himself remains an enigma. Our expert, Lucia Gahlin, examines his story

A coloured version of a photograph of Howard Carter examining Tutankhamun’s mummy-shaped coffin

‘The mystery of his life still eludes us… the shadows move but the dark is never quite dispersed’

Archaeologist Howard Carter, who with his team discovered the tomb in 1922

A detail from Tutankhamun’s throne, with the pharaoh and his wife shown beneath the rays of Akhenaten’s one god, Aten

A detail from Tutankhamun’s throne, with the pharaoh and his wife shown beneath the rays of Akhenaten’s one god, Aten

1. WHAT'S IN A NAME?

We all know the name ‘Tutankhamun’, but the tale of the boy king, dead at just 20, remains a mystery.

His fame comes not from his short reign (c.1336–27 BC), nor the extent to which his rule was taken up with restoring order and orthodoxy, following his heretical and revolutionary father, Akhenaten’s, time on the throne. More, Tutankhamun is a household name because his has been the only pharaoh’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings to be discovered virtually intact.

We say ‘virtually’ because the tomb had been robbed at least twice before its discovery by archaeologist Howard Carter and his team in 1922 – and those robberies seemingly happened months after burial. Still, when Carter and his team excavated they found, in the archaeologist’s words, ‘Wonderful things’, including the iconic solid gold funerary mask.

These are wondrous treasures, but what do we know of the king they were buried with?

We know him as Tutankhamun, but he was in fact named Tutankhaten (‘living image of Aten’) at birth, and was called that until a couple of years into his reign. This name can still be seen on a cartouche on the elaborately gilded and inlaid throne found in his tomb.

Names were significant in ancient Egypt. When this prince was born, he was called after the one god worshipped in his father’s reign. Worshipping one god was unheard of before Akhenaten. He was a pharaoh who went against convention, making changes to the art and ideology of Egyptian kingship. He was the only ruler in 3,000 or so years of pharaonic Egyptian history to change the traditional polytheistic religion (belief in more than one god), to a form of monotheism, the worship of the sun god Aten.

A clue that there was a return to royal, religious and artistic ‘normality’ during Tutankhamun’s reign is that his name was changed to one that celebrated Amun, one of many gods, instead of his father’s sole deity, Aten.

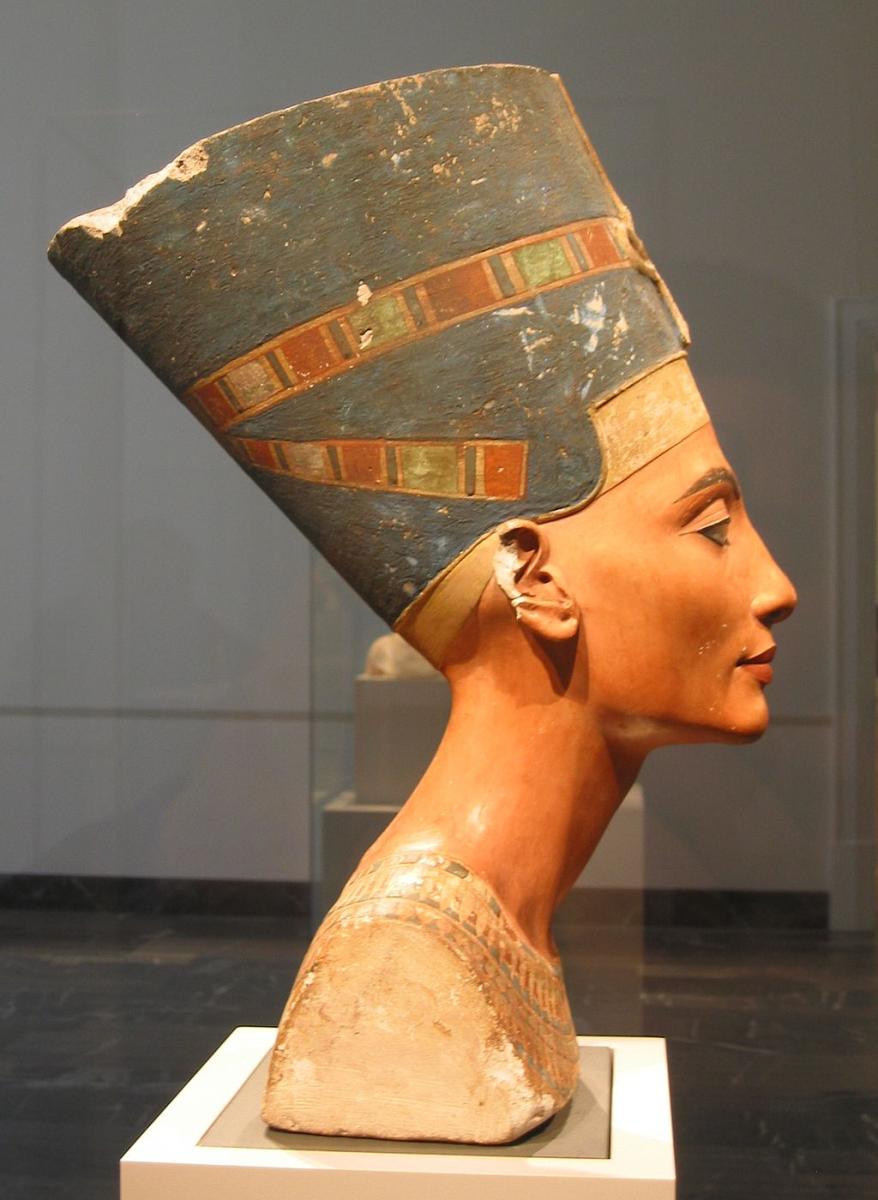

This painted limestone and plaster bust of Nefertiti was discovered in 1912 in a sculptor’s workshop at Amarna; it is now in the Neues Museum, Berlin

This painted limestone and plaster bust of Nefertiti was discovered in 1912 in a sculptor’s workshop at Amarna; it is now in the Neues Museum, Berlin

2. FEMALE INFLUENCES

Tutankhamun was surrounded by strong women with whom he had spent his early years.

We may not be certain who his mother was (she was perhaps one of his father’s multiple wives, Kiya), but his beautiful stepmother, Nefertiti, was clearly an influential figure. Considered by many to have been ancient Egypt’s most famous queen, she may have co-ruled alongside her husband Akhenaten at the end of his reign, and possibly acted as co-regent to her young stepson at the start of his.

Tutankhamun’s wife, Ankhesenamun, appears with him on the back panel of his inlaid gilded wooden throne (as seen in point 1), as well as on inlaid boxes and gilded shrines, all found in his tomb. The fact she is shown alongside her husband, and to the same scale, in the art of this period indicates her significance and is peculiar to this period of ancient Egyptian art. Royal iconography always expresses the royal ideology, and the importance of the role of the queen is being emphasised. Ankhesenamun was a daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and so is likely to have been one of Tutankhamun’s half sisters. However, when we explore this period of Egyptian history we find nothing is certain, as the sources can be interpreted in a variety of ways and there are gaps in the record. It is even possible, for example, that Tutankhamun was a son of Nefertiti.

Curiously we can be more certain of a lesser figure in Tutankhamun’s life – his wet nurse. Her name was Maia and her decorated tomb at Saqqara has only been open to visitors since 2015. On it she is depicted in carved relief with her pet dog by her side and Tutankhamun on her lap. In ancient Egypt only a tiny minority were granted the privilege of a decorated tomb, and there are very few belonging to non-royal women. Noblewomen were usually buried in tombs with their husbands, and it is the men who feature on the walls of these tombs. We can only conjecture that Maia must have been considered a figure of some importance.

The Abydos king list in Seti I’s temple at Abydos; those pharaohs, including Tutankhamun, who were thought not to have ruled in accordance with the ancient Egyptian concept of maat (all that was right and proper) were omitted

The Abydos king list in Seti I’s temple at Abydos; those pharaohs, including Tutankhamun, who were thought not to have ruled in accordance with the ancient Egyptian concept of maat (all that was right and proper) were omitted

3. ANCIENT CANCEL CULTURE

Although Tutankhamun may be the name that springs to mind when we think of ancient Egypt, it appears he was no more than a puppet king. There were powerful people making the major decisions during his reign.

His chief adviser was Ay, a nobleman who held sway during Akhenaten’s reign, and then ruled Egypt on the death of the boy king. This was an unexpected outcome, as it appears that Tutankhamun’s designated heir, should he die without a son, was in fact his military commander, Horemheb, who became pharaoh on the death of Ay.

Horemheb was behind the decision to write Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Ay out of history, and he had their names excised from the monuments of Egypt. We know that decision was based on Akhenaten’s changes to art and religion, which were believed to have flown in the face of the ancient Egyptian concept of maat (order – all that was right and proper). The decision was taken to forget him, his son and their loyal adviser. Today, for example, if you visit the temple of Seti I at Abydos, you will find a list of pharaohs, going back to the first ruler of Egypt, carved on the temple wall; the names of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun and Ay are not there. Recent history had been whitewashed. Tutankhamun was deleted from the records – and collective conscience – within 50 years of his death, because of his father’s revolutionary innovations.

So the pharaoh whose name is known best to us today, is a pharaoh whose name the ancient Egyptians chose to forget.

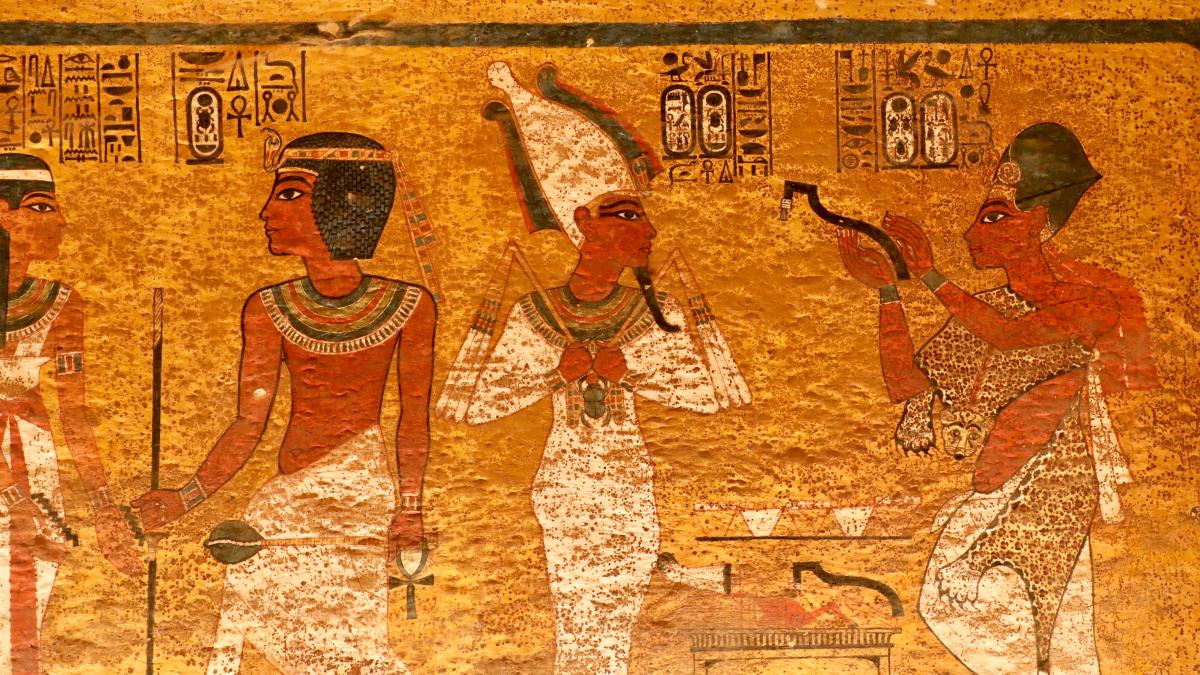

The performance of the ritual known as ‘Opening of the Mouth’ painted on the wall of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber

The performance of the ritual known as ‘Opening of the Mouth’ painted on the wall of Tutankhamun’s burial chamber

4. A SUSPICIOUS TOMB SWAP?

Visually, Tutankhamun’s tomb smacks of intrigue.

Its design is not typical of a pharaoh’s tomb but rather that of a noble personage. A clear parallel can be seen in the tomb of Tutankhamun’s non-royal grandparents, Yuya and Thuya, in the Valley of the Kings, which, despite its modern name, was also a cemetery for privileged courtiers.

The plot thickens when we consider Ay’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

It is located close to that of Tutankhamun’s grandfather, Amenhotep III, and cut to the design of his father Akhenaten’s tomb at Amarna. It seems likely that Ay’s royal tomb was begun for Tutankhamun, and that the tomb the young pharaoh was placed in was likely intended for Ay, as a nobleman.

Could such a tomb switch have taken place?

As pharaoh, having claimed the throne on Tutankhamun’s death, Ay would have been in a position to make such a decision. The usual 70 days between death and burial in ancient Egypt would have been long enough to paint the walls of a small burial chamber for the boy king. The art on these walls is unusual. This is the only tomb of a pharaoh to have a depiction of his funeral painted on the wall. Ay’s audacity is written large in the form of a painting of him performing the ‘Opening of the Mouth’ ceremony on the mummified body of the deceased pharaoh. This was a ritual to reignite the life force and restore the senses of the deceased, so that he was reanimated for the eternal pharaonic afterlife. By presenting himself in this role Ay was legitimising his claim to the throne.

A hot topic of debate in Egyptology today is whether Tutankhamun’s solid gold, inlaid funerary mask is a reworked hand-me-down

A hot topic of debate in Egyptology today is whether Tutankhamun’s solid gold, inlaid funerary mask is a reworked hand-me-down

5. ANCIENT RECYCLING

In addition to what appears to have been the upcycling of a tomb for Tutankhamun, it now appears that a number of treasures interred with the boy king had been recycled.

Recent analysis suggests that pieces, including some of the best known, were likely reused and sometimes reinscribed or reworked for this burial. Could Tutankhamun’s iconic funerary mask, for example, have been originally intended for Nefertiti? It’s just possible.

This tomb was packed with funerary paraphernalia as well as magnificent furniture and other items of daily life clearly brought from the palace. The huge number of objects, in slight disarray, crammed into the four small rooms of this tomb give the impression that a decision had been taken following the death of Tutankhamun to offload anything accessible, whether funerary or domestic, that was in any way associated with this royal family.

For example, the famous statue of Anubis was wrapped in a linen shawl inscribed with the name of Akhenaten, and a paint palette found between the paws of Anubis was inscribed for Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s eldest daughter, Meritaten. The ‘Amarna royal family’ had clearly fallen from grace owing to Akhenaten’s extreme changes to state religion, art and kingship ideology, all of which underpinned ancient Egyptian society and belief.

All the treasures found in Tutankhamun's tomb will soon go on display at Cairo’s new Grand Egyptian Museum. But 100 years on from the discovery of his tomb the mystery of his life still eludes us.

LUCIA'S TOP TIPS

Places to go

Soon it will be possible to visit the entire collection of 5,000 treasures from Tutankhamun’s tomb, when they go on display together for the first time. This will be at the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo, planned to open in November 2022. Pick a tour to Egypt that also includes the Valley of the Kings, Saqqara, Amarna and Abydos.

Closer to home, museums in the UK house fine collections of Egyptian antiquities relating to Tutankhamun and his family, particularly the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford and the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London. The Petrie Museum will have a centennial exhibition on Tutankhamun’s childhood called Tutankhamun the Boy: Growing Up in Ancient Egypt. Check for confirmed dates on the museum’s website.

And do visit the special display Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford, open until February 2023. This fascinating exhibition will show some of the archival material (including photographs) from the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Explore online

The Griffith Institute in Oxford houses the archive for the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, which includes Harry Burton’s photographs and Howard Carter’s drawings. It is entirely online and called Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation.

Find out more about the mysteries of Tutankhamun’s life and burial by listening to these podcasts by a host of eminent Egyptologists.

A good read

So much has been written about the tomb, its discovery and treasures; one excellent book is The Unknown Tutankhamun by Marianne Eaton-Krauss (2015), published by Bloomsbury.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT EMAIL...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story

Images: Howard Carter and sarcophagus © Giancarlo Costa/Bridgeman Images; Tutankhamun’s throne, Nefertiti head and funerary mask from WikiCommons; Abydos king list from Flickr; Tutankhamun’s burial chamber © Shutterstock.

About the Author

Lucia Gahlin

Lucia is an Egyptologist. She has been an Arts Society Lecturer for 10 years and has taught for a number of UK universities including London, Bristol and Exeter. She leads tours to Egypt (including for Andante Travels) and gives guided tours of museums with Egyptian collections. She has worked at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London, and at the archaeological site of Amarna in Egypt. She has authored many books including Egypt: Gods, Myths and Religion. Lucia’s lectures for The Arts Society include ‘Wonderful Things!’ Tutankhamun’s tomb and treasures, The mythologising of a pharaoh: Akhenaten, deformed or divine? and Nefertiti: images of Ancient Egypt’s most intriguing queen.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition