This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on...the art and design of the Olympic Games

Become an instant expert on...the art and design of the Olympic Games

16 Jul 2024

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition

The Runners by Robert Delaunay, 1926. Image: © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

‘Citius, Altius, Fortius – Communiter (Faster, Higher, Stronger – Together)’

The Olympic motto

The Olympic rings on display at the London Olympics, 2012. Image: Simon Inglis

1. Who created the famed five rings?

Born in Paris in 1863, Baron Pierre de Coubertin is best remembered for one thing in particular. He masterminded the revival of the ancient Olympic Games, starting at Athens in 1896. As the son of an artist, Coubertin also recognised the importance of visual identity for his revived games. As a result, in 1913 he adapted the two-ringed logo of the French sporting organisation he led to form the famous five-ring Olympic emblem we know today.

Brilliantly simple and as recognisable as any of the world’s leading commercial logos, the interlocking rings represent the five continents considered at the time to be inhabited. Coubertin’s choice of colours were those found most commonly on national flags. Since making its debut at the Antwerp Games in 1920, the five-ring symbol has featured on countless posters, merchandise, coins and postage stamps; today any such exposure is strictly monitored by the Lausanne-based International Olympic Committee (IOC).

In 1963 a curious story about the famous rings emerged.

Two American authors, writing about the Olympics, stated that the symbol originated in ancient Greece. They claimed to have seen an example engraved on a stone in the stadium at Delphi. This statement set off one of many false trails to have muddled Olympic history. It was later revealed that the stone in question had in fact been a film prop, made for the set of a scene in director Leni Riefenstahl’s famous, or infamous, propaganda film Olympia, about the 1936 Olympics.

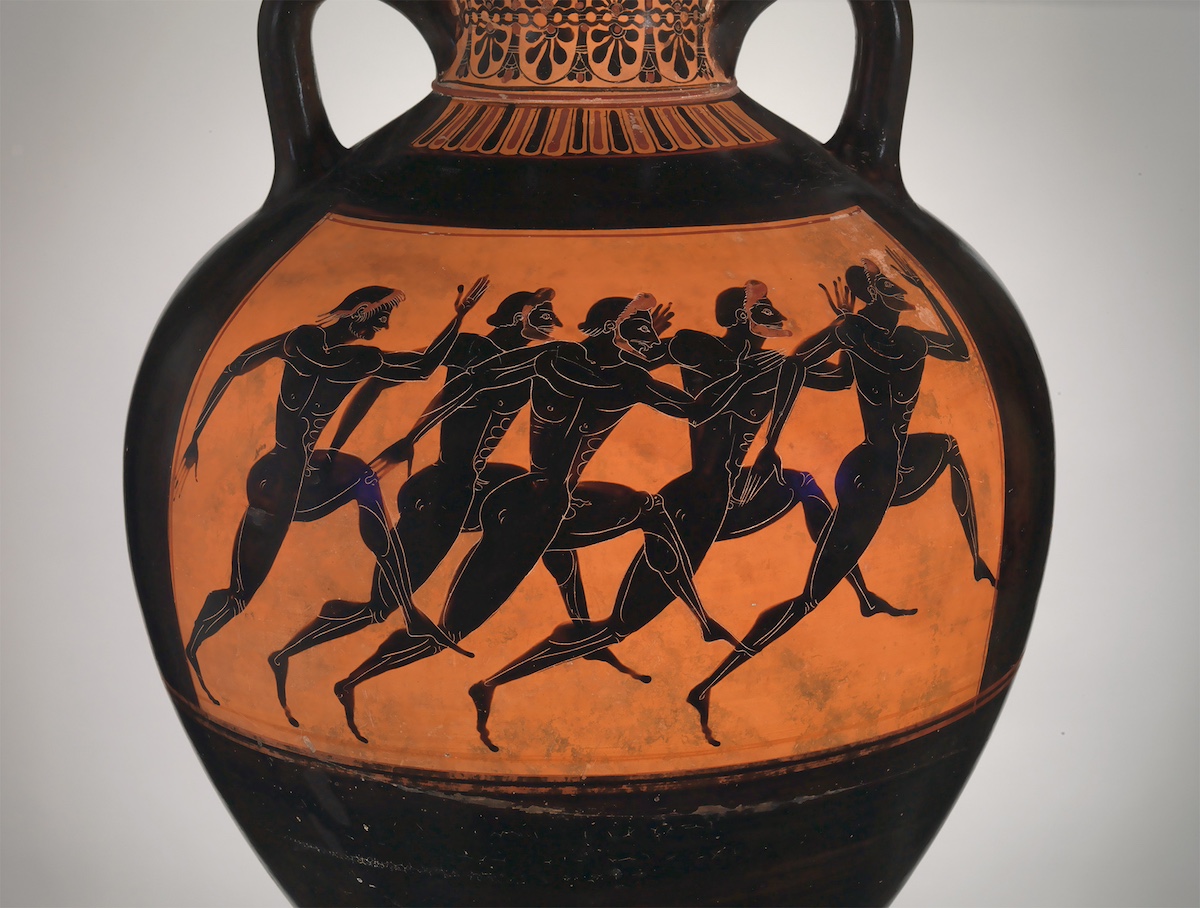

The Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora, attributed to the Euphiletos Painter. Image: The Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art); Rogers Fund, 1914

The Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora, attributed to the Euphiletos Painter. Image: The Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art); Rogers Fund, 1914

2. Naked ambition

The amphora above proves just how closely – and how long – artists have followed the Games.

It dates to the Panathenaic Games of c.530 BC. It also nudges us to note how, as athletes’ sportswear becomes ever more skimpy and body-hugging, we should consider that at major games in ancient Greece the participants, all male, would have been naked.

This amphora is attributed to the painter Euphiletos, who was using a black-figure technique found commonly on pottery of the period. The figures also reveal just how, kit and footwear apart, the physiques of sprinters and their running styles have changed little since.

Other elements of the Games also draw strongly on the past. At Olympia the track was approximately 192m long, a measurement known in ancient Greek as a stade. It is from this measurement that we get stadion (in Greek) and stadium (in Latin). Similarly the word gymnasium derives from the Greek gymnos, meaning naked or bare.

With all that flesh on display – at least until more chaste Roman tastes prevailed – women were not only banned from spectating but, if caught, threatened with being thrown off the rocky heights that overlooked Olympia. Yet, as recorded by the writer and traveller Pausanias, at other times and in other locations, such as Sparta, women actually competed in their own athletic contests.

Coubertin opposed the participation of women in the modern Games. He considered their inclusion, from 1900 onwards, to have been ‘impractical, uninteresting, ungainly’ and even ‘improper’. It was not until 1928 that female athletes were admitted to Olympic track and field events. This situation was even worse in the corridors of power, where membership of the IOC remained exclusively male until 1981.

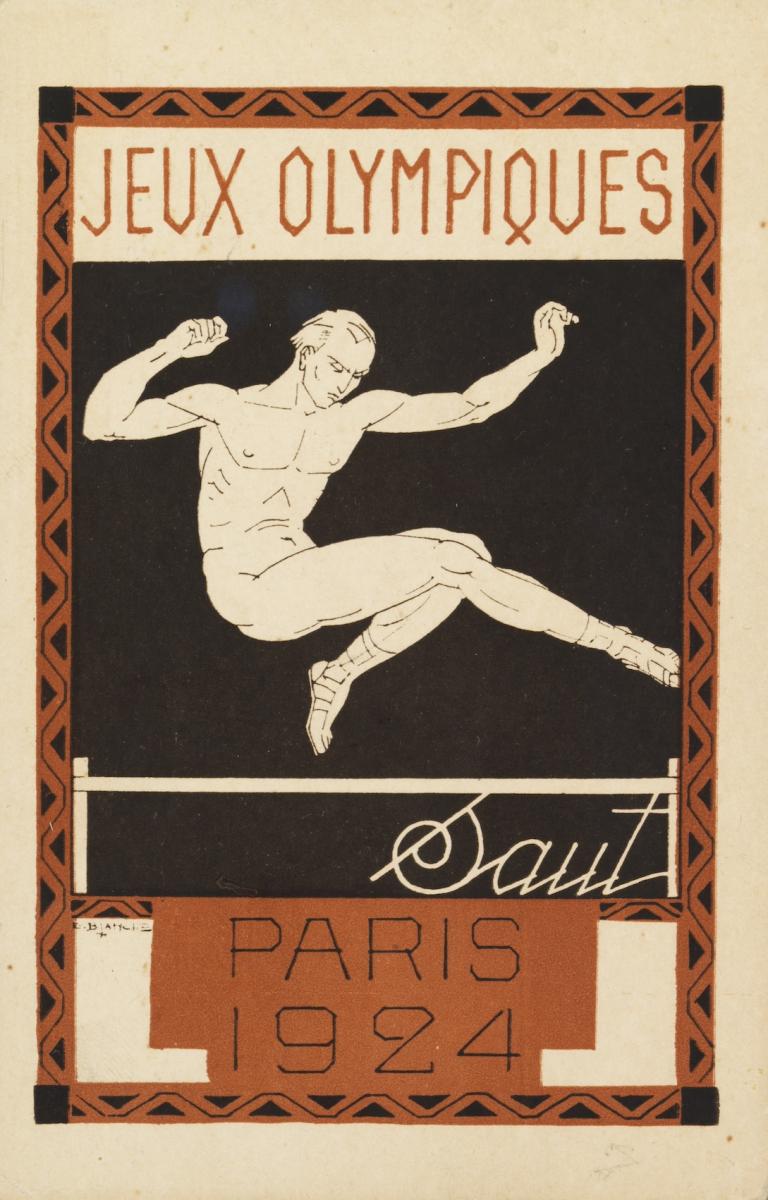

One of a set of eight postcards by E Blanche, printed by Henri Francois, showing a high jumper, 1924. Image: © Collections Musée National du Sport, France

One of a set of eight postcards by E Blanche, printed by Henri Francois, showing a high jumper, 1924. Image: © Collections Musée National du Sport, France

3. Competitive art

Art and, more recently, graphic design have played a defining role in the presentation and identity of each modern Olympics. And at one point art and design were even part of the competition.

From the 1912 games in Stockholm until London’s so-called ‘Austerity Olympics’ in 1948, there were Olympic competitions in five artistic disciplines: painting, sculpture, architecture, literature and music.

Each entry had to have been inspired by sport. Sadly, few winning entries appear to have earned much attention. The idea, so full of potential, was eventually dropped due to lack of interest and the fear that, at a time when amateurism was still fundamental to the Olympic ethos – as it would remain at least nominally until 1992 – professional artists might prevail.

Official Olympic posters and illustrative material, conversely, offered professional artists a unique platform – a situation that continues today.

London’s poster in 1948 was the work of the painter and illustrator Walter Herz. The 1968 Olympic Stadium in Mexico City featured a large mosaic by Diego Rivera. The dissident artist Ai Weiwei, despite his anti-government stance, was a consultant to the architects of Beijing's extraordinary ‘Bird’s Nest’ stadium, built for the 2008 Summer Olympics. Four years later Thomas Heatherwick designed the distinctive Olympic torches and cauldron for the London Games.

In a wider context, all Olympic hosts are now required to organise a Cultural Olympiad; as a result hundreds of cultural events will be happening across Paris this summer. Among the offerings are a giant tapestry on display at the beautiful Hôtel de la Marine on the Place de la Concorde; a Vogue fashion show at the Place Vendôme; and of course frequent appearances by France’s favourite historical figure, Asterix the Gaul.

This year’s medals for Paris 2024. Image: Thomas Deschamps, courtesy Olympics Paris 2024

This year’s medals for Paris 2024. Image: Thomas Deschamps, courtesy Olympics Paris 2024

4. Resting on their laurels

At the four leading ‘Sacred Games’ of ancient Greece, held over a four-year cycle (or Olympiad) at Delphi, Nemea, Corinth and Olympia, victors were crowned with garlands or wreaths, and there were no prizes for coming second.

At Nemea these crowns were formed using wild celery. At Olympia wild olive (kotinos) was preferred. Such crowns had no monetary worth although more lavish gifts, such as amphorae filled with highly valued olive oil, were often awarded at other, lesser games.

The modern practice of conferring medals appears to have originated in Britain where, at an early revival of the Olympics staged at Much Wenlock in Shropshire – an event that inspired Coubertin to embark on his campaign to initiate a full international revival – medals started to appear in the 1860s.

Yet it was not until the third modern Olympics, held in St Louis, Missouri in 1904, that the now standard issue of gold, silver and bronze came into being.

Until 1920 the gold medal was indeed made of gold. Since then winners medals have been predominantly silver, with a few grams of gold added as gilt, while bronze medals have typically been fashioned from copper. Every host city designs its own medals, using strict parameters laid down by the IOC. Like all previous hosts, Paris has retained the tradition of depicting the Greek goddess of victory, Nike, bearing an olive wreath and a palm frond, to symbolise peace.

In addition, each of the 5,084 medals to have been struck carry an extra, unique touch: a hexagonal piece of iron sourced from the original Eiffel Tower, set in a sunburst pattern typical of the work of Maison Chaumet, the first jewellers ever to have been entrusted with the design of Olympic medals. In another nod to French history, the Paralympic medals bear the date written in braille, which, like the modern Games themselves, was the brainchild of a Frenchman.

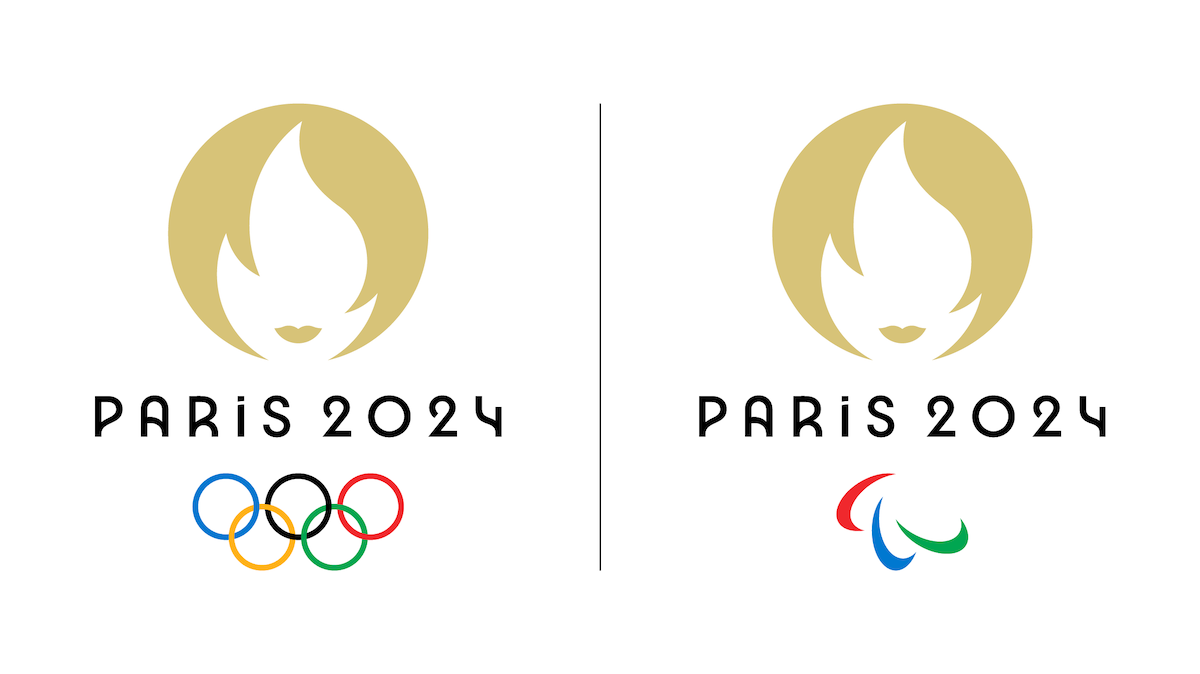

Paris 2024’s double emblem. Image: Courtesy Olympic Paris 2024

Paris 2024’s double emblem. Image: Courtesy Olympic Paris 2024

5. Winning designs

From stamps to stadiums, medals to merchandise, every four years designers crave a spot in the Olympic limelight. Do you recall Stella McCartney’s flag-inspired kit designs for the 2012 Team GB? Or, also from 2012, the controversy over the design agency Wolff Olins’ logo for the London Games, with its juxtaposition of five jagged, interlocking shapes? This time round there should be no such quibbling. As the official blurb puts it, the Paris 2024 emblem, formed by the overlay of three distinct and iconic symbols, ‘combines images with playful audacity’ while remaining ‘quintessentially French’.

In the background lies a round gold medal, pierced by the outline of the Olympic flame (a flame which, incidentally, only entered the Olympic canon during the 1936 games in Berlin). On their own these two images might not have much visual impact, but this being France the designers have cleverly, one might say mischievously, added the slightly upturned lips of a woman. Naturally the woman is Marianne, the national personification of La République since the French Revolution, whose likeness is found in town halls, and on stamps, coins, posters and propaganda material across France.

As an aside, the 2024 Paris mascots have a similar provenance, being based on the Phrygian (or liberty) cap popularly worn by French revolutionaries and often by Marianne herself.

A little bit radical, a little seductive, but overall decidedly cool, the golden visage of this Games’ double emblem sits above the words ‘Paris 2024’. And to bring matters full circle, those words are set in a specially designed Neo Deco font, itself an homage to the Art Deco style that came into being around the time of the last Paris Olympics in 1924.

Simon’s top tips

Great reads

Among countless books on the Olympic Games, The Ancient Olympics by Nigel Spivey offers a highly readable account of what it was really like at Olympia, with its stench of sacrificial meat and inadequate latrines.

Martin Polley’s The British Olympics: Britain’s Olympic Heritage 1612–2012 reveals how important the British were in reviving the Games between 1616 and 1896.

For a more contemporary critical appraisal, The Games: A Global History of the Olympics by David Goldblatt focuses on the many controversies, geopolitical, cultural and social, that have shaped the Olympic movement in the last century.

Visit

If visiting any part of France this year, check out local events forming part of the Cultural Olympiad under the banner Terre de Jeux 2024.

Among those events the Louvre is staging the exhibition Olympism: Modern Invention, Ancient Legacy until 16 September; louvre.fr. At the Centre Pompidou you can take an interactive tour of the modern and contemporary art in the collection, while exploring the links between art and sport. Find more information on the tour, entitled When All is at Stake and on until 10 August at centrepompidou.fr

In the UK from 19 July–3 November the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge has its show Paris 1924: Sport, Art and the Body, which explores how the Modernist culture of Paris shaped the future of sport and the Olympic Games as we know them today; fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Find out more

The International Olympic Committee’s official website, olympics.com, features a range of material, including, in its ‘Museum’ section, examples of stunning Olympic posters going back to 1896. Search within the site for ‘Olympic Art Posters’.

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

About the Author

Simon Inglis

has been an Accredited Lecturer with The Arts Society since 2017, a role he took on after editing the Played in Britain series for English Heritage for 15 years. His main area of interest is the heritage of sport and recreation. For Paris 2024 Simon is offering a lecture on the art and design of the Olympics entitled The Athletic Aesthetic. Other talks include Great Lengths, on the art and architecture of swimming, Making a Stand: sporting architecture, list it or lose it? and A Load of Old Balls, a lecture on how balls encapsulate design, technology and human ingenuity. His book Football Grounds of Britain was described in The Guardian as the best sports book of the 20th century, while The Daily Telegraph has called Simon ‘a national treasure who must be encouraged at all costs’

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition