This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on Angels in the Arts

Become an Instant Expert on Angels in the Arts

13 Dec 2021

From the earliest painters to William Blake and on to Antony Gormley, artists have always been fascinated by angels – but are these celestial beings messengers or missiles? Our expert, Caroline Holmes, examines the evidence

An angelic fresco by Antonio Palomino in the Monasterio de la Cartuja

‛The Angel that presided o'er my birth / Said, "Little creature, form'd of Joy and Mirth, / "Go love without the help of any Thing on Earth."’

William Blake, poet, painter and printmaker (1757–1827)

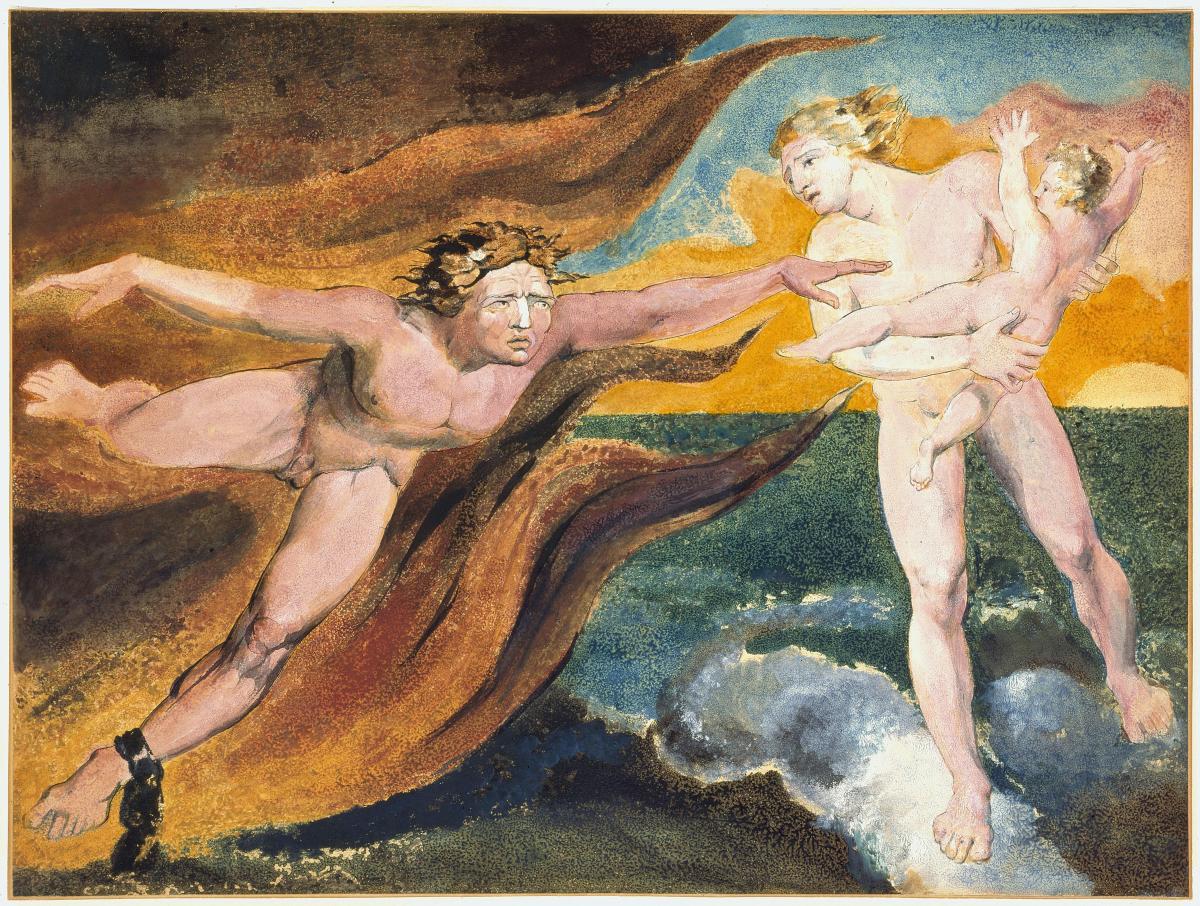

William Blake’s The Good and Evil Angels Struggling for Possession of a Child

1. FOUR WINGS OR TWO?

In the history of art, what forms do angels take?

They appear in all three of the Abrahamic faiths, associated with light, ardour and purity, and are shown, in their simplest form, as a child’s head with wings.

According to traditional Christian angelology, there is a ninefold celestial hierarchy. It is topped by the six-winged seraphim, the ‘fiery ones’, filled with burning love above God’s throne. Two wings were used to fly, two to cover their faces and two their feet – gloriously represented in action as frescos on Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia.

Cherubim are of the second order, with two pairs of wings and occasionally four faces: a lion to represent wild animals, an ox for domestic animals, a human for humanity and an eagle for birds. More importantly, cherubim are especially associated with love.

The word 'angel' stems from the Greek 'άγγελος' or 'aggelos' – messenger – but make no mistake, to be a divine messenger requires more than being decorative.

William Blake’s tiny poem, quoted above, is in stark contrast to his The Good and Evil Angels Struggling for Possession of a Child, which explores whether active evil is better than passive good. The dark Gothic appearance of the evil angel embodies late 18th-century notions of wickedness, while the symbolism of virtue is manifest in the light whiteness of the good angel. Look a little closer: would you want your child in the hands of someone strong but dubious, or a benign dreamer likely to drop him or her?

Going back to the dawn of time, who was first, the angels or man? For Marc Chagall (1877–1985) angels came first. In his Bible series, begun in 1958, he walks the tightrope between the sacred and the profane, athletically balancing his Russian Jewish roots and post-Holocaust Christian surroundings in a kaleidoscope of action-packed colour. Underlining the fact that, for him, angels were present from the very beginning, his The Creation of Man depicts an angel gently holding the newly formed Adam.

Fra Angelico’s The Annunciation

2. CONVEYING MESSAGES

Artists have used angels in many forms to convey a range of pure and complex celestial symbols to their audience.

Take The Annunciation by Fra Angelico (c.1395–1455), which is housed at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid.

Within the work, beyond Mary’s temple, we see an angel herding Adam and Eve out of the Garden of Eden, while a divine beam carries the dove representing the Holy Spirit across the canvas. Intricately patterned wings support the serene Archangel Gabriel as Mary receives the message of her Immaculate Conception and future motherhood of the Son of God.

More powerful messaging comes from Jean Cocteau (1889–1963), who conceived a series of Old and New Testament mosaics for the new Notre Dame de Jerusalem church above Fréjus in 1962 (which were not actually implemented until 1992). His The Annunciation encapsulates messages of power and awe. With dazzling blue wings made from broken Murano glass, the mighty Archangel Gabriel towers over Mary, whose red robe echoes the colours of Fra Angelico’s work of the same title, but not its dreamy sentiment. The extraordinary message – of Christianity’s genesis in the form of Jesus – is delivered directly into Mary’s head and mind; her right hand on Gabriel’s knee both completes the circle and for me suggests a surrogate, or perhaps surreal, womb.

The Fountain of the Fallen Angel in Retiro Park, Madrid

The Fountain of the Fallen Angel in Retiro Park, Madrid

3. THE FIGHT AGAINST EVIL

To meet the four original archangels (and other angels) read Milton’s Paradise Lost, published in 1667.The scenery described takes you on a headlong journey of damnation and redemption. Lucifer, brother of the sword-bearing Archangel Michael, was the light bearer given charge of heavenly worship and praise to God, until he became the first fallen angel and transposed to become Satan.

In the words of Milton’s Canto 1:

'Him the Almighty Power / Hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky, / With hideous ruin and combustion, down / To bottomless perdition…'

This drama is hauntingly evoked in the carved face convulsed by fear created by sculptor Ricardo Bellver (1845–1924) in his The Fountain of the Fallen Angel in Madrid. The pedestal for this, designed by architect Francisco Jareño (1818–92), has alarming devils gripping fish, lizards and snakes.

Returning to Paradise Lost, Milton provided contrast to such darkness. He describes how Gabriel counters the ‘dreams of evil’ whispered by Satan into Eve’s ear as she lies with Adam on their nuptial bed. Gabriel despatches two cherubim, Ithuriel and Zephon, to the scene. This scene was evocatively used by Blake when he illustrated Paradise Lost in 1808, featuring love-quenched Adam and Eve and nearby Satan, ‘squat like a toad’, watched by these powerful cherubim. A touch of Ithuriel’s spear destroys Satan’s disguise.

Angel of Peace, The Boer War (South African) Memorial in Cardiff

4. ANGELS OF PEACE

In seeking angels of a more peaceful but powerful variety, we can head to Cardiff, for a particularly forceful example: Angel of Peace, the Boer War (South African) Memorial, sculpted by Albert Toft (1862–1949).

Described as an idealist, Toft countered that to become an idealist you must necessarily first be a realist. Topped by an angel of peace, his sculpture is dedicated ‘To the memory of the Welshmen who fell in South Africa, 1899–1902’.

The angel’s sculpted wings control her flight as her feet touch down. Her message of peace is stressed by the fact that in her hand she holds not an olive branch but a tree with roots ready to be planted to mark better future times.

Another sculptor to use angels to express peace was the Expressionist Ernst Barlach (1870–1938). He focused on faces and hands, the bodies detached from earth and time. After World War I Barlach became a pacifist and, on Whit Sunday 1927, his bronze Hovering or Floating Angel (Der Schwebende) was placed at Güstrow Cathedral in Germany, as a memorial to the war.

Within a year Nazism had declared his angel ‘degenerate art’. It was removed in a silent ceremony and melted down; fortuitously, a secret plaster cast had been taken.

After World War II a new angel was made and hung in Cologne Cathedral as a memorial to both wars; later, a second was placed back at Güstrow. In December 1981 Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and German Democratic Republic Chairman Erich Honecker met under Barlach’s angel and the Bishop of Mecklenburg talked of a shared past. Schmidt hoped it represented a shared future.

Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North

5. AN ANGEL FOR THE NORTH

When asked why he created an angel for his famous 1998 sculpture for Gateshead – the Angel of the North – Antony Gormley replied: ‘The only response I can give is that no one has ever seen one and we need to keep imagining them. The angel has three functions: firstly, a historic one to remind us that below this site coal miners worked in the dark for 200 years; secondly, to grasp hold of the future, expressing our transition from the industrial to the information age, and lastly to be a focus for our hopes and fears.’

Angel of the North, standing at 65ft with a wingspan of 175ft, is reputedly the world’s largest angel sculpture. Commissioned by Gateshead Council, there are 3,153 individual steel pieces in the body and two wings. It represents the catalyst for the regeneration of Gateshead Quays, Gateshead Millennium Bridge, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art and Sage Gateshead. It is also said to be one of the most viewed pieces of art in the world, seen, says Gateshead Council, by more than one person every second. That amounts to 33 million people a year.

CAROLINE'S TOP TIPS

Head to East Anglia

Many East Anglian churches share the Byzantium tradition of carved angels gracing their roofs, as in St Mary Magdalene, Sandringham. Carved, painted and gilded, these angels evoke Luke’s account of the angel’s appearance to the shepherds: ‘Be not afraid … And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude.’ Think of the royal family on Christmas Day in this church; one pew end has the Angel Gabriel and Mary, the other an angel comforting Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane.

The Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid

This is where you will see Fra Angelico’s The Annunciation.

Tate Britain

The gallery holds a number of William Blake’s works. For more, see here.

Look closely

If any of your Christmas cards this year show an angel, try to read the message the angel is conveying – love, beauty, light or protection. You’ll see faces of power, gentleness, serenity and mischievousness, and wings of artistic complexity. Angels are shown as acrobatic, physical or ethereal. The list is endless.

A good read

There are multiple books to read on angels, but an excellent short introduction to their presence in the history of art comes with A Closer Look: Angels by Erika Langmuir, published by The National Gallery.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT FEATURE...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

Show me another Instant Expert story

Images: Antonio Palomino's fresco © Shutterstock; The Good and Evil Angels Struggling for Possession of a Child © Alamy/PP9RGG; The Annunciation © Alamy/CTONKP; The Fountain of the Fallen Angel © Shutterstock; Angel of Peace photograph © Caroline Holmes; Angel of the North © Shutterstock.

About the Author

Caroline Holmes

Caroline is a garden historian who speaks internationally, live and online, weaving art, landscape and literature to create a detailed picture of her subjects. She can be seen on Viking TV speaking about Monet’s garden at Giverny. She is an academic tutor and course director for the University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education and the author of 12 books. For more on her work, see horti-history.com. Among her lectures for The Arts Society are Messenger or Missile? Angels – glad tidings, doom, gloom or perdition? A symphony in blue – the artist, the couturier, Atlas – the most fabulous mountaine of all Africke, Monet at Giverny and Impressionists in their Gardens – living light and colour.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition