This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Wartime Evacuation of London's Precious Artworks

Become an Instant Expert on the Wartime Evacuation of London's Precious Artworks

9 Nov 2021

World War II curators were prepared to go to extraordinary lengths to hide (in unlikely sites) the UK’s dazzling art collection. Our expert, Caroline Shenton, takes up the tale

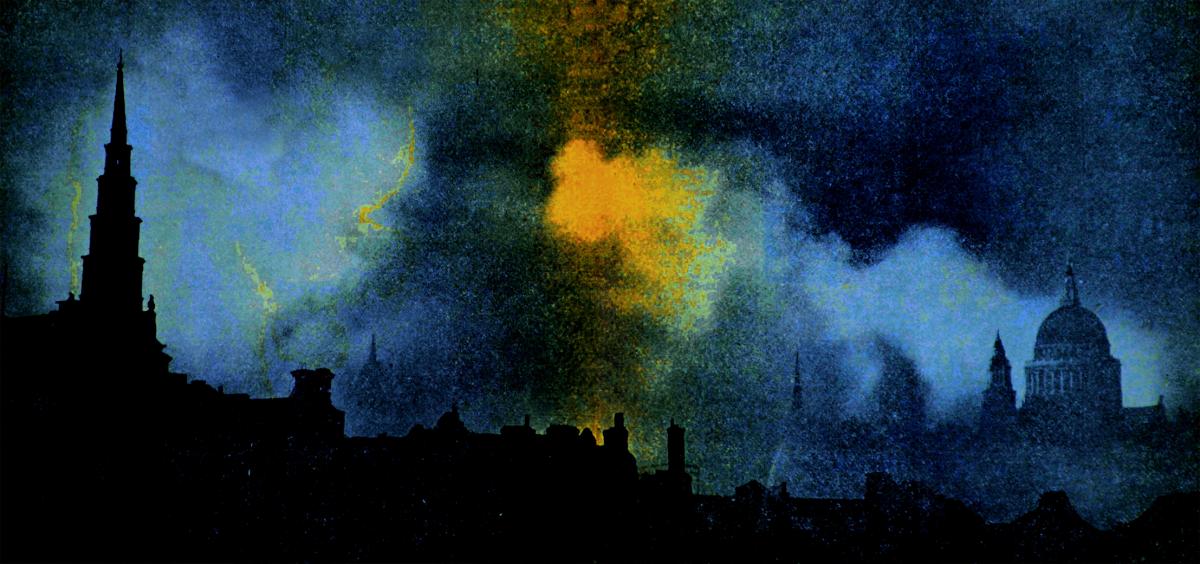

The London Blitz, a hand-coloured photograph from 1940

The London Blitz, a hand-coloured photograph from 1940

‘Hide them in caves and cellars, but not one picture shall leave this island… None must go. We are going to beat them’

Winston Churchill, May 1940

Guernica on display in Paris in 1937, before travelling to London

Guernica on display in Paris in 1937, before travelling to London

1. THE GATHERING STORM

From 1933, curators of London’s national museums and galleries watched events unfolding in Germany with increasing anxiety.

World War I still cast a shadow over a generation of curators who had served on the Western Front. Their fears were initially focused on the possibility of the capital being hit by air raids involving poison gas, such as had been deployed in the trenches. As time went on, however, it became clear that other perils would face London’s collections if the Nazis succeeded in invading Britain.

So-called ‘degenerate’ Modern art was certain to be confiscated and destroyed. Jewish-owned masterpieces would be seized and added to Goering’s bloated art collection, or auctioned off in Switzerland to fill the coffers back in Berlin. Jewish and German émigré staff working in London’s cultural institutions and listed in the Gestapo’s Black Book would be arrested on sight. Some objects might even be used for propaganda purposes to shore up the racial ideology of the National Socialist Party (such as occurred, later in the war, to the Bayeux Tapestry in Normandy, reclassified as a Viking ‘Aryan’ artefact).

The bombing of the Prado in Madrid in 1936 during the Spanish Civil War and the arrival of Picasso’s Guernica on tour in Britain on 30 September 1938 (coincidentally the same day that the Munich Agreement was signed) seared into the minds of all those charged with protecting London’s collections the likely outcome of the approaching catastrophe.

The V&A Museum’s van and horse and cart being loaded with treasure

The V&A Museum’s van and horse and cart being loaded with treasure

2. MONUMENTS MEN... AND WOMEN

Action had to be taken.

Establishment figures like John Forsdyke at the British Museum, Kenneth Clark at the National Gallery, James Mann at the Wallace Collection and other directors of major museums and galleries were in overall charge of their institutions’ arrangements, in liaison with Whitehall departments.

The hands-on work was done by a small army of curators, conservators and warders under their command, tasked with getting thousands of their precious charges out of the city.

It was a moment in our history when a remarkable coalition of mild-mannered civil servants, eccentric professionals and metropolitan aesthetes became the front line in the heritage war against Hitler. These people were often those who had never quite fitted into peacetime society: they were square pegs in round holes. Figures of fun or even targets of suspicion at work, and often uncomfortable in their surroundings, they now stepped out of the shadows.

One example was Ian Rawlins, a deeply introverted but brilliant physicist who was paid a retainer by the National Gallery to run its conservation laboratory. His obsession with railway timetables proved vital in formulating the gallery’s escape plans.

Elsewhere, female curators, who had only been permitted to take up professional roles in the previous 10 or 15 years, were able to prove themselves when their male counterparts were called up or transferred to secret duties. For instance, at the Victoria and Albert Museum, academic spinster Muriel Clayton, recruited in 1926 as one of its first professional female curators, found herself in charge of the museum’s evacuation to Montacute House in Somerset.

Tunnelled away: a helmet from the Sutton Hoo collection

Tunnelled away: a helmet from the Sutton Hoo collection

3. SECRET PLACES

A few museum collections, particularly those of sculpture, remained in London, some sandbagged in place if they were just too heavy to move.

London Underground tunnels were pressed into service to shelter not just people, but also antiquities. The Parthenon (Elgin) Marbles were hidden in the depths of Aldwych Tube station, as was the Sutton Hoo treasure, acquired by the British Museum only days before war broke out.

For the majority of the capital’s most precious heritage, however, hiding places across England and Wales were found, stretching from the Home Counties to all points north and west of London – even as far as the Welsh coast.

The Office of Works had the power to requisition property for war purposes (including private houses with over four bedrooms), and by the late 1930s, working with the galleries and museums, it had created a secret list of possible refuges for collections.

Some country house owners, sensing what might happen, offered up their homes in advance in the hope that providing space for paintings and decorative art would prevent schools or squaddies being billeted on them instead. ‘After all,’ pleaded one stately home owner near Peterborough, threatened with having to accommodate a boarding school for young ladies, ‘we do know that girls can be produced at any time by the processes of nature; but Old Masters are quite irreplaceable.’

Aristocratic and gentry owners got more than they bargained for, finding themselves pushed out of their comfortable sitting rooms and libraries to make way for the new arrivals. Tensions were rife between warders and servants. And heating bills rocketed as they struggled to maintain stable conditions for their troublesome guests in their manor houses and castles.

Curious places to conceal: Manod Mawr in Snowdonia

Curious places to conceal: Manod Mawr in Snowdonia

4. UNDERGROUND RESISTANCE

While initial plans assumed that, once in their safe houses, collections would stay put for as long as necessary, with the fall of France in May 1940 views changed.

Luftwaffe attacks were being launched from northern France; it became clear that collections stored above ground near major targets such as Liverpool, Birmingham and Bristol were as vulnerable to bombing as if they had remained in London.

As the Blitz pummelled their buildings back in the capital, some national institutions began to plan for a second move, which would provide further protection for their evacuated collections in the countryside.

The most famous of these was that of the National Gallery which, following intense planning by Ian Rawlins, was moved into specially constructed, environmentally controlled brick sheds inside a slate mine in Manod Mawr in Snowdonia. Over the course of five weeks in the summer of 1941, some 2,000 paintings scattered across six safe houses in Wales and Gloucestershire were moved by rail to Blaenau Ffestiniog, then transported by van up a windswept four-mile mountain track to their new home.

Another major underground store was established in a former mushroom farm at Westwood Quarry, near Avoncliff in the Mendips. In 1942 it took on some of the collections of the British Museum, National Portrait Gallery and V&A, in another wave of urgent moves. When journalists tried to uncover the exact locations of these secret stores, the locals stubbornly kept quiet about their priceless neighbours.

Safe and on view: works of art at Tate Britain today

Safe and on view: works of art at Tate Britain today

5. FINEST HOUR

Most collections returned to London between D-Day and VE Day, but some of the British Museum’s collection remained in the London Underground well into the late 1940s. By that time alarm about the Soviet Union and potential nuclear war brought the issue of subterranean storage once more into the minds of London’s museum and gallery directors.

Happily this never needed to be invoked.

Post-World War II all the collections returned to a changed world. They had escaped the fate of works that remained behind in London. Many of the buildings they left, however, had been badly damaged through the Blitz and V2 attacks – the Tate Gallery (today Tate Britain), the Imperial War Museum and the British Museum being the worst affected; they were only fully restored again in the 1960s.

But there were benefits too.

Conservation science took an enormous leap forward through what National Gallery and British Museum conservators had managed to establish with controlled environmental conditions in their underground storage. Today’s international standards for heritage storage – much refined – are based on the conditions for organic material that were established during the war.

A number of the curators and conservators involved received knighthoods or other civilian honours for their efforts. The story of this ‘other’ evacuation is a reminder that even the most unlikely people have a part to play in wartime. To paraphrase Milton: they also serve, who only store and wait.

CAROLINE'S TOP TIPS

Visit

A large number of country houses across England and Wales were used to house national collections. Some are open to the public today but rarely make mention of their wartime guests. Among them are:

Boughton House, Northamptonshire, where the British Museum stored hundreds of crates of antiquities in the Great Hall and Egyptian Hall, leaving behind rust marks on the marble floors.

Hellens Manor, Herefordshire, where the Tate Gallery stored about a third of its collections under the watchful eye of the formidable Lady Helena Gleichen.

Penrhyn Castle, Gwynedd, where the National Gallery stored its colossal Van Dyck Equestrian Portrait of Charles I in the garage (former stables) block, and other paintings in the dining room.

View

The V&A was badly damaged in the Blitz. Walk down the side of the building to see the pockmarked stonework, which has become the museum’s war memorial.

Read

My latest book National Treasures: Saving the Nation’s Art in World War II (John Murray, 2021) will be published on 11 November. In it, I tell the extraordinary and sometimes hilarious story of how the band of heroic curators and eccentric custodians from London’s major galleries, museums, archives and libraries saved the capital’s collections during World War II.

About the Author

Caroline Shenton

Arts Society Lecturer Dr Caroline Shenton is an archivist, historian and former director of the Parliamentary Archives. Educated at St Andrews, Oxford and UCL, her first popular history book, The Day Parliament Burned Down, was shortlisted for a number of prizes and won top prize at the inaugural Political Book Awards in 2013. Its sequel, Mr Barry’s War, was a book of the year for BBC History Magazine and The Daily Telegraph. Among Caroline’s lectures for The Arts Society are those on both the old and new Houses of Parliament, as well as Votes for Women! Art of the Suffragettes and Packing Up the Nation: Saving London’s Museums and Galleries in World War II(the topic of this Instant Expert).

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition