This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the History of the World in Five Symbols

Become an Instant Expert on the History of the World in Five Symbols

16 Aug 2021

Unlocking the hidden meanings of cultural symbols sheds new light on ideas that have driven history. Our expert, Matthew Wilson, explores the tales behind five great examples

Fountains at Villa d’Este in Italy: but when is a fountain not just a fountain, but a symbol of potent – and political – meaning? Read on…

Equestrian Portrait of Elisabeth de France, wife of Philip IV of Spain (c.1635), by Diego Velázquez

1. THE COVETABLE PEARL

In Suetonius’s De vita Caesarum (AD 121) the historian provided an interesting explanation of why the Romans invaded Britain – it was the lure of the barbarian country’s rivers, which were rumoured to be full of pearls.

The same bait, apparently, hooked the Spanish into funding Christopher Columbus’s quest for westward passage to the Indies. The pattern is the same further back in history: as far ago as the 6th millennium BC, the enormous value of pearls led to transnational trade networks that linked fishing sites with inland settlements.

It is not often that we consider aesthetic objects as the motivation for life-or-death adventures into the unknown, or for costly wars to subdue foreign lands. But that is the role pearls have often played. The trace of their powerful grasp over the human spirit is captured in art, in images of the wealthy, powerful or glamorous.

For example, the pearl around the Queen of Spain’s neck in Diego Velázquez’s 1635 portrait (seen here) was known as ‘La Peregrina’. It was found in the Gulf of Panama in the late 16th century. As the largest pearl then discovered, it was the centrepiece of the Spanish crown jewels and featured in countless court portraits by artists, including Rubens and Juan Pantoja de la Cruz.

After being owned by Napoleon III and James Hamilton, Duke of Abercorn, it ended up in the possession of Elizabeth Taylor in 1969.

Aside from denoting power and imperial reach, pearls have also functioned in art as a symbol of ultimate beauty in their association with Venus, and the divine purity of the Virgin Mary. They are the luxury item that lured humanity to the ends of the earth and allowed them to see the perfection of heaven.

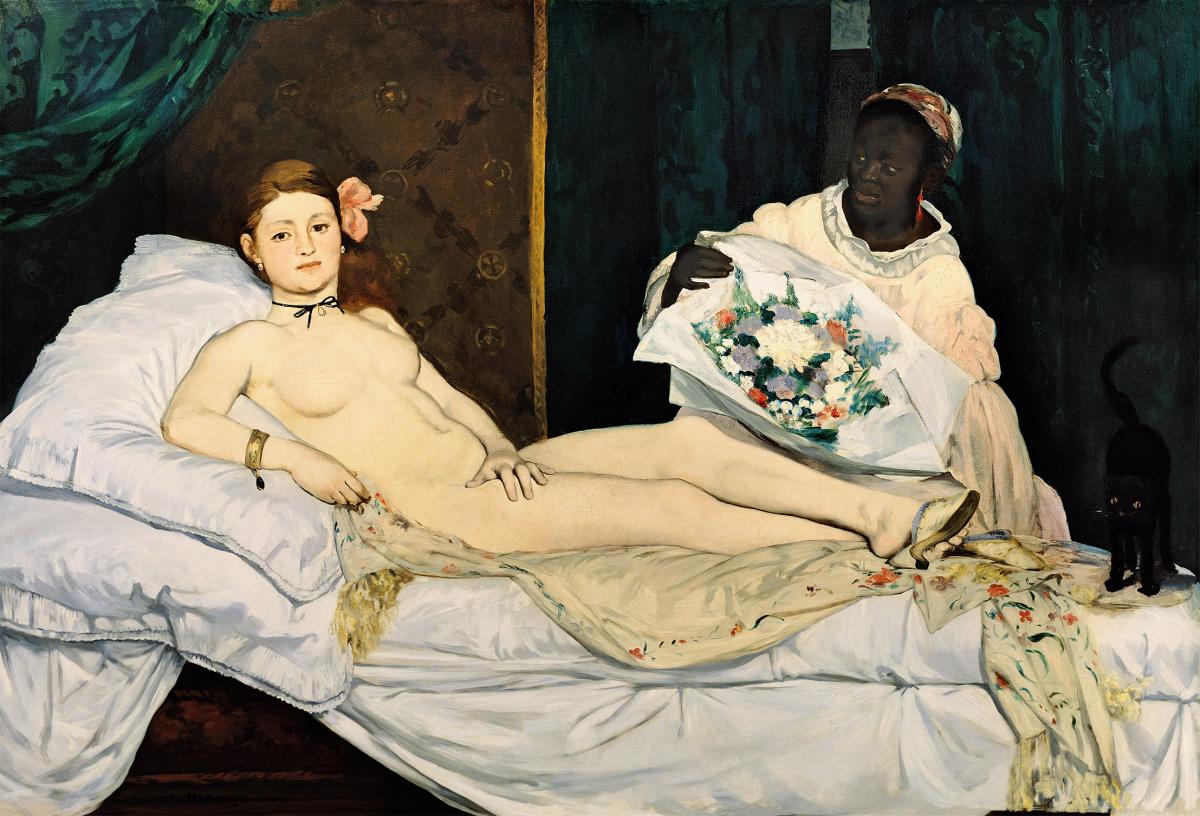

Spot the arched black cat in Édouard Manet’s Olympia

2. ENIGMATIC CATS

Why is the black cat in artworks, such as this in Manet’s Olympia (1863), often seen by art historians to be a symbol of degeneracy and sin? The answer opens a window onto the evolution of religion, and the history of women within them.

Cats connoted femininity and illustriousness in ancient Egypt. Bastet was an Egyptian cat goddess, and her status is recorded in many elegant feline statuettes that were created in her honour, some of which were decorated with valuable accessories, such as earrings.

But cats would fare less favourably in Christian Europe.

Medieval bestiaries (books that compiled knowledge of animals and their symbolism, often accompanied by images) described cats as lecherous. A papal bull issued by Pope Gregory IX in 1233 dealt their reputation an even more fateful blow. It called for the abolition of diabolical cults that were rumoured to have sprung up in Europe, some of which involved cat worship. It was all unpleasantly reminiscent of Norse mythology, where the goddess Freya travelled around in a chariot drawn by a team of cats, not to mention Bastet’s benighted rites in ancient Egypt. Added to this, the Bible never mentioned domesticated cats, giving Pope Gregory strong liturgical backing for associating them with evil.

The unpalatable cults reported in 1233 fed into folklore about witches and their feline companions. Bastet, the feminine deity of auspicious cats, was dead, and the demonic witches of Europe would hitherto cast black moggies as common symbols of (normally female) wickedness.

The Fountain of Neptune, Villa d’Este, Tivoli, Italy

3. FOUNTAINS AND POWER

Symbolising a source of pure, drinkable water, fountains have been linked in the Abrahamic religions with spiritual vitality and God’s beneficence.

You will find decorative fountains in almost every major city in the world. It’s the inheritance of a tradition that saw them as political statements: by commissioning fountains, rulers demonstrated their own sense of generosity, while simultaneously suggesting a God-like ability to control nature. Cities cannot exist without predictable water supplies, and the quantity and the design of fountains symbolises engineering skills and economic prosperity.

The Minoans of the Greek Cycladic islands (c.3000–1100 BC) were among the first civilisations to create high-pressure water fountains. But it was to be the Romans who were the first true masters of hydrotechnology. By the time of the fall of the western Roman Empire, in the 5th century AD, the city of Rome had 1,352 public fountains, fed by aqueducts conveying water into the city from far-distant mountain springs.

The end of the western Roman Empire brought with it the fading of knowledge about hydraulic engineering and, in turn, the dilapidation of the aqueduct system. As such, fountains would not appear again in Italian cities until the 13th century, when ancient engineering knowledge was rediscovered.

Later, the design of civic fountains became ever more dramatic and elaborate, often incorporating a cast of classical gods or allegories to ennoble the ensemble. The bombastic fountains decorating the gardens of the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, Italy (1550) became the inspiration for many subsequent garden fountains in stately homes across Europe, symbolising humanity’s capacity for marshalling water, the pure elixir of life, through technology.

A gold five guinea piece of 1686

4. THE ELEPHANT AND CASTLE

Beneath the head of King James II on this 1686 five guinea coin is a curious emblem: an elephant with a castle.

The reason why it appears in this context takes us on a history of global trade and empire, spanning nearly two millennia.

The symbol started its life at a specific battle in 326 BC. When Alexander the Great fought the armies of King Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes in the Punjab region of India, the Macedonian was astounded to see battle elephants carrying howdahs full of troops in the ranks of his foe.

After the conflict, coins were struck showing this outlandish weapon of war. It stuck in the iconography of European design, handed down as a signifier of exotic and mighty far-distant kingdoms.

One iteration was in the signage of companies such as the City of London’s Worshipful Company of Cutlers, whose members used elephant ivory in the handles of tableware they made.

The reason it was used on British guinea coins is similar: the Royal Africa Company, founded in 1660, had been awarded a monopoly to trade and exploit natural resources on the west coast of Africa, particularly gold and ivory. As such, the guineas made from the company's African gold were demarcated by the elephant and castle symbol.

In this context it declares the aspirations of an emerging British Empire to conquer enemies at the edges of the known world, like Alexander the Great, and dispossess them of their most lucrative natural commodities for trade.

A Vanitas Still Life with a Skull, a Book and Roses (c.1630) by Jan Davidsz de Heem

5. SKULLS AND SURPRISES

Skulls have long appeared in art. In early Christian artworks they were occasionally depicted at the base of the cross, because the site of Christ’s burial, Golgotha, was, in St Mark’s Gospel, ‘the place of the skull’.

The skull as a symbol of death had its heyday in art in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in ‘vanitas’ paintings – a genre that underscored the futility of worldly possessions and reminded viewers of the inevitability of death. Skulls flooded artistic iconography during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Why was this? Was it connected with particularly apocalyptic events of the period, like the Black Death, or the Hundred Years War?

Curiously, it’s possible the reason may not have been in response to an escalation in death, but in wealth. With the development of capitalism in Europe came a new social group – the middle class – who were newly prosperous and keen purchasers of luxury goods. The guilt associated with this affluence and its seeming incompatibility with Christian values led the wealthy to seek out and possess symbols of humility.

The skull served the purpose brilliantly, especially in the wealthy, capitalist Dutch Republic, where vanitas paintings were created and avidly consumed.

In time skulls began to feature increasingly in art all over Europe, including in Catholic countries, where they appeared beside Mary Magdalene, St Jerome, St Ignatius Loyola and other death-contemplating saints.

So although the skull may seem like a timeless symbol, it actually owes its popularity to new economic conditions: the rise of capitalism.

MATTHEW'S TOP TIPS

See

There are so many great paintings to recommend. I have limited myself to just four gems that you can see in the UK:

Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533) at The National Gallery, London – to admire a cornucopia of cryptic visual symbols, including its famous anamorphic skull.

Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I (1514), one of three large prints, demonstrates possibly the most famous application of symbols in a work of art – its meanings are still hotly debated. See it at the Scottish National Gallery, The British Museum, London and elsewhere.

William Holman Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd (1851) at Manchester Art Gallery: a great example to see to learn how the Pre-Raphaelites used symbols to enrich moral tales.

Max Ernst’s Men Shall Know Nothing of This (1923) at Tate Modern, London shows how Surrealism twisted ancient alchemical symbols to powerful effect.

Read

You can read about a selection of symbols and their hidden meanings in my books Symbols in Art (2020) and The Hidden Language of Symbols, forthcoming 2022 (both published by Thames & Hudson).

Brief overviews of many cross-cultural symbols can be found in the excellent Hall’s Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art, 1994 (John Murray).

A classic text on understanding cultures through their symbols is Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance, 1939 (Oxford University Press) by Erwin Panofsky.

A very different aspect of symbols is dealt with in the influential Man and his Symbols, 1964 (Aldus Books) conceived and edited by Carl Jung.

About the Author

Matthew Wilson

Matthew Wilson studied history of art at The Courtauld Institute and has been a teacher of the subject in secondary schools in the UK for over a decade. As a freelance writer he has also written for numerous publications, including the BBC, Aesthetica magazine and Smarthistory – the world’s most-used art historical resource. His latest book is Symbols in Art (Thames & Hudson, 2020) and he is currently working on The Hidden Language of Symbols, also on the subject of iconography, due for publication in 2022. Among his talks for The Arts Society are The artists who outwitted the Nazis, Caravaggio: violence and veneration in the 17th century and Europe and Japan: an artistic love story.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition