This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Influence of Britain's Seaside on Modern British Art

Become an Instant Expert on the Influence of Britain's Seaside on Modern British Art

20 Jul 2021

In the first half of the 20th century, the artists spearheading British modern art looked to the coast for inspiration. The curator of a new exhibition on this subject, James Russell, reveals the results

Epidauros II, by Barbara Hepworth, above the sea at St Ives, Cornwall

‘I have gained very great inspiration from Cornish land- and sea-scape, the horizontal line of the sea and the quality of light and colour which reminds me of the Mediterranean light and colour which so excites one's sense of form…’

Barbara Hepworth, quoted in The Studio, 1946

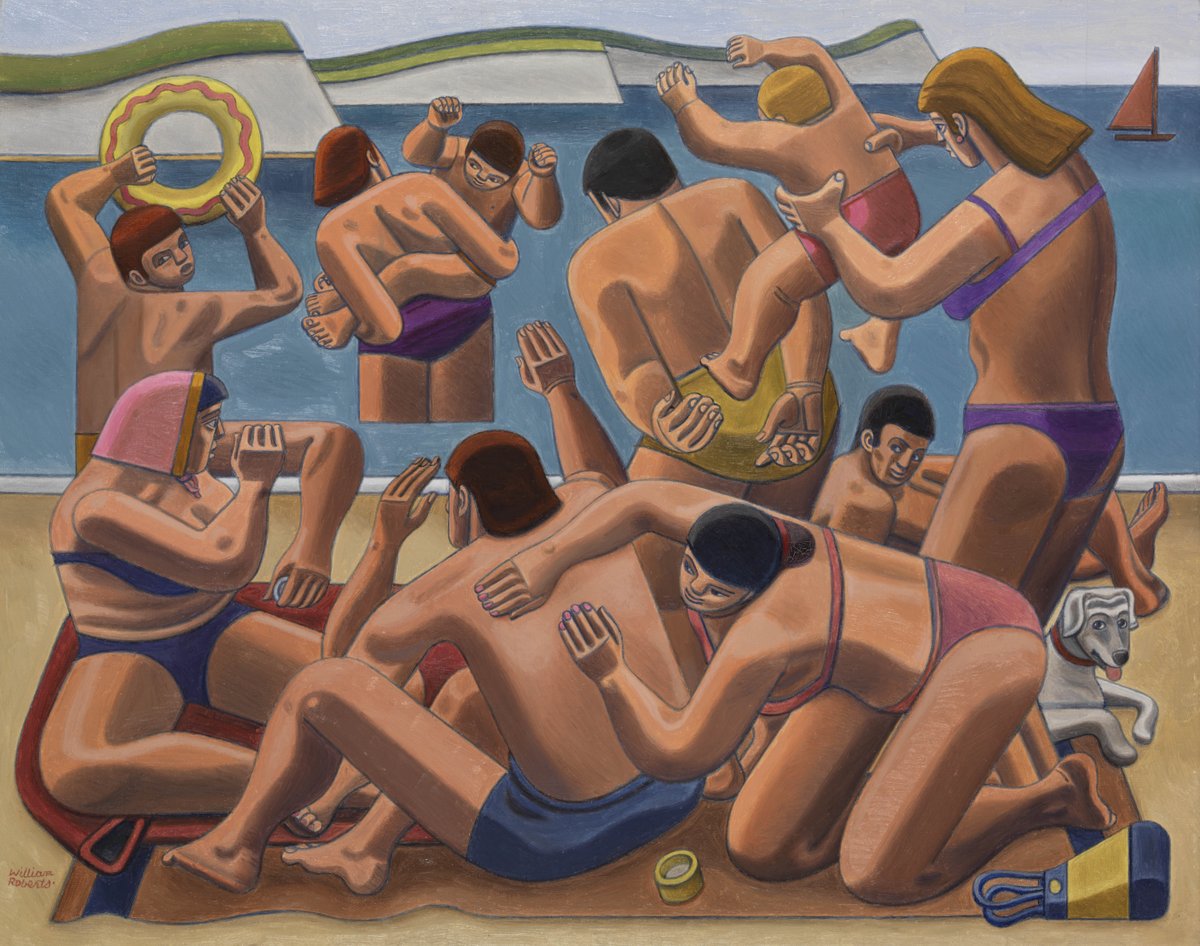

The Seaside, c.1966, by William Roberts

1. CELEBRATING THE SEASIDE

Seaside Modern: Art and Life on the Beach is an exhibition that celebrates the artists who established the British beach as a key site for British modern art. The exhibition looks at the achievements of the painters, sculptors, photographers and printmakers, not to mention the designers, whose sun-drenched posters lured holidaymakers to resorts around the country.

The end of World War I heralded a new age of leisure and brought fresh freedoms. Having been segregated during the 19th century, women and men could now enjoy the beach together. As scientists discovered the beneficial effects of sunlight – in combatting tuberculosis and metabolising vitamin D – a suntan became the height of fashion. Meanwhile, progressive government legislation ensured that by the end of the 1930s everyone was entitled to a precious week’s paid holiday.

Towards the end of a long career, William Roberts (1895–1980) painted a group of day trippers on the beach, choreographing their gestures to create a kind of monumental dance. Roberts had a distinctive and not particularly flattering approach to painting figures, but in The Seaside (above) his warm feelings for an ordinary scene come through in the hands either rubbing on sunscreen, or cupped ready to receive a child’s feet. At the same time every limb is perfectly placed, creating a composition that is as elegant in its way as a frieze on a Greek temple.

The Cruise, painted by Mary Adshead in 1934

2. A NEW WORLD OF LEISURE

It’s worth comparing the intimately connected group shown in The Seaside with the one depicted by Mary Adshead (1904–95) in The Cruise. A successful mural painter who deserves greater recognition as a fine artist, Adshead joined a cruise in the early 1930s and evidently studied her fellow passengers with care.

The result is a painting that captures both the physical awkwardness of life on the breezy deck and the complex dynamics of the group. There is agitation everywhere: in the bent head of the steward with his precariously balanced tea tray; in the glances passing between the passengers and, most of all, in the anguished expression of the man on the left, struggling with his patterned rug.

This interest in the human spectacle of holidaymaking was part of a wider fascination for the ever-changing region at the border of land and sea.

John Constable (1776–1837) was one of the first artists to focus on the beach as a subject in its own right. He blazed a trail that was followed by others, once oil paint became available in easily portable tubes. By the 1860s Parisian artists were abandoning their studios to work en plein air in Brittany, making the most of coastal sunshine and the local colour provided by working fishermen and women in traditional dress.

By the 1880s, forward-looking British painters were doing the same thing in Cornwall. As the 20th century got under way and the beach evolved from workplace to holiday destination, the process was observed by Laura Knight (1877–1970), LS Lowry (1887–1976) and other artists inspired by this new world of leisure.

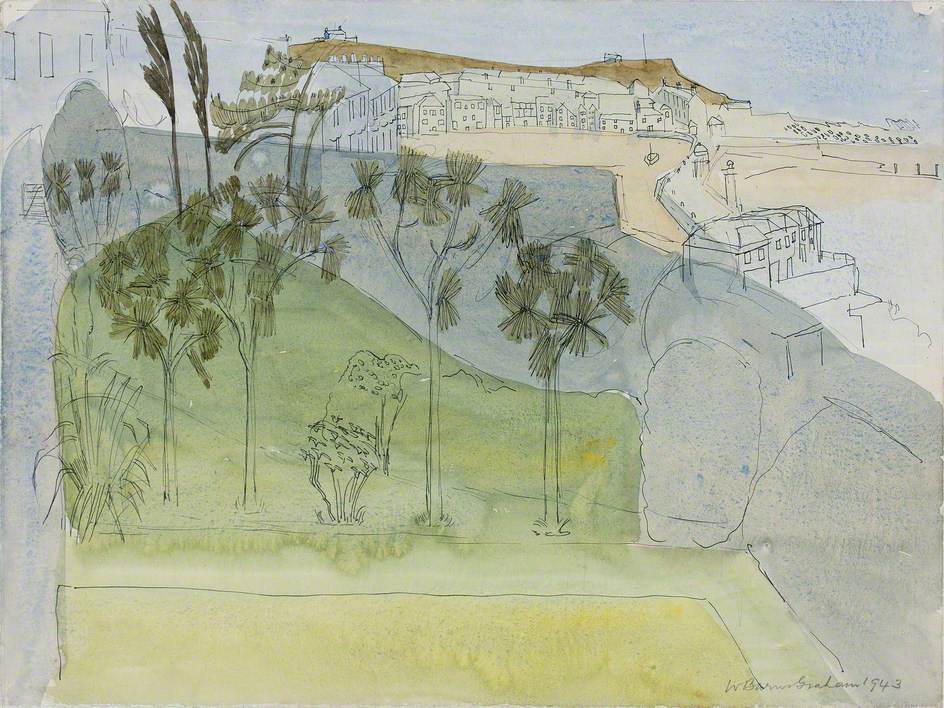

Untitled (View of St Ives), 1943, in pen and ink and watercolour, by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham

3. MODERN ARTISTS ON THE BEACH

Artists didn't just observe holidaymakers, of course – they occasionally went on holiday themselves. In the early 1930s Barbara Hepworth (1903–75) invited friends, including fellow sculptor Henry Moore (1898–1986) and painter Ben Nicholson (1894–1982), for working holidays on the beach at Happisburgh in Norfolk.

Hepworth and Moore studied the effects of erosion on rocks and pebbles, using their findings as they learned how to carve holes through stone.

Meanwhile Hepworth and Nicholson embarked on a love affair that was as passionately aesthetic as it was romantic. By the end of the decade they were husband and wife, parents of triplets and Britain’s most celebrated champions of modern Abstract art.

When they moved to St Ives in Cornwall at the outbreak of World War II their fame attracted other modern artists. These included Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (1912–2004), a Scottish painter whose wartime drawings of St Ives have a marvellous delicacy and precision. In her vision the old fishing port is transformed into a modern resort, complete with palm trees.

Rye Harbour, a watercolour and pencil work by Eric Ravilious, 1938

4. INTO THE LIGHT

For Eric Ravilious (1903–42), clear light and cloudless skies were the main attractions of the coast. In preparation for an exhibition in 1939, he made good use of fine weather to paint watercolours at Tollesbury in Essex and Aldeburgh in Suffolk, where he rose at dawn to draw bathing machines on the beach.

Travelling on to Rye Harbour in Sussex he found himself in a small but thriving colony of artists. As he sat, drawing board on knee, squinting into the sun, a woman introduced herself as the owner of a school for watercolour students. He accepted her invitation to visit her studio for a glass of sherry, although he never fully established whether she knew who he was – or hoped he might become a pupil.

Also staying nearby was Edward Le Bas (1904–66), a painter and collector. When Ravilious showed Le Bas the unfinished Rye Harbour he insisted on buying it there and then; all these years later it is not hard to see why.

This watercolour could be a monument to an age that revered sunlight. We see the bright summer sun reflected on the burnished surface of the water and on the drying mud, and then our gaze is led away down the channel towards the distant sea. Faintly discernible in the heat haze is the distinctive Rye Lighthouse.

Eileen Agar’s Photograph of a beached tree, 1936

5. STRANGE SHORES

During the 1930s the rise of Surrealism encouraged artists to seek in the external world the kind of subjects that reflected the interior world of dreams and imagination. The beach proved a fertile hunting ground.

Paul Nash (1889–1946) and Eileen Agar (1899–1991) met by chance in 1935, in the Dorset seaside town of Swanage. Imaginative and unconventional, both were fascinated by the flotsam left on the beach by the retreating tide, and particularly by objects that resembled creatures or monsters.

Born in Argentina to British parents, Agar had an international outlook and an unusual visual imagination that found its expression most often in collages and constructions. She took the photograph shown here in France, the summer after her sojourn in Swanage. Stripped of its bark, the beached tree protrudes from the sand like the skeleton of some exotic creature.

The outbreak of World War II saw Britain’s beaches transformed into a Surrealist vision of concrete blocks, pillboxes and barbed wire. But after five lost summers the invasion defences were cleared away and the day trippers returned.

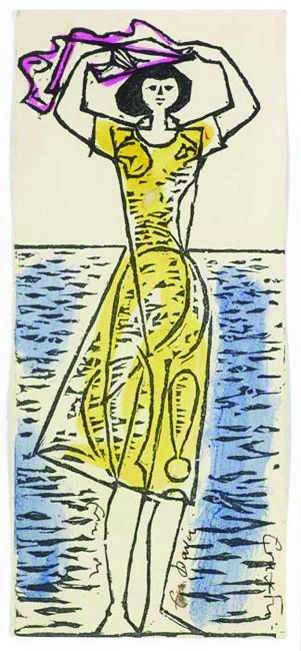

They did so with a vengeance, but by the 1950s there were hints of what lay ahead. When John Craxton (1922–2009) began visiting Greece he was something of a pioneer, but his linocut of a young woman at the water’s edge captures the warmth and brightness that would, over the next 20 years, entice more and more people away from Britain’s beaches towards the sun-soaked sands of the Mediterranean coast.

John Craxton’s 1957 linocut, Girl with Scarf by the Sea

JAMES'S TOP TIPS

VISIT

Seaside Modern: Art and Life on the Beach is at Hastings Contemporary until 31 October. It features paintings, sculpture, works on paper, posters and photographs by Eric Ravilious, Paul Nash, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore and a host of other artists, both the well known and those worthy of discovery. Book your ticket before you visit.

READ

The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated 60-page catalogue. The essay explores the lives and work of the artists featured in the exhibition, teasing out relationships and showing how the British coast, and particularly our beaches, inspired the 20th century’s most exciting artists.

EXPLORE

The Coastal Culture Trail. If you’re feeling energetic it’s 18 miles from Towner Eastbourne to Hastings Contemporary – a route that takes in the De La Warr Pavilion (Bexhill-on-Sea) on the way. Other travel methods are available – see here for details.

About the Author

James Russell

James Russell is an art historian who enjoys finding new ways of looking at 20th-century British art and design. He curated the 2015 exhibition Ravilious at Dulwich Picture Gallery and the 2019 exhibition Reflection: British Art in an Age of Change at Ferens Art Gallery, Hull. James studied history at Pembroke College, Cambridge. A leading authority on the work of Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden, he has written more than a dozen books on these and other artists, with The Lost Watercolours of Edward Bawden being a 2016 Sunday Times Book of the Year. His lectures for The Arts Society include Seaside Modern: Art and Life on the Beach, Eric Ravilious: Life and Work and Edward Seago: From the Circus to Sandringham.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition