This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on early Hollywood’s sparkle

Become an instant expert on early Hollywood’s sparkle

24 Nov 2020

In Hollywood’s early years, stars like Rudolph Valentino and Greta Garbo may have been the public face of the movies, but it was the people who worked behind the cameras who really made the magic happen. They turned hat-check girls, waitresses, cowboys and cab drivers into silver screen icons. Our expert, Geri Parlby, reveals their stories.

Hollywood glamour. The poster for The Barkleys of Broadway

Hollywood glamour. The poster for The Barkleys of Broadway

In Hollywood’s early years, stars like Rudolph Valentino and Greta Garbo may have been the public face of the movies, but it was the people who worked behind the cameras who really made the magic happen. They turned hat-check girls, waitresses, cowboys and cab drivers into silver screen icons. Our expert, Geri Parlby, reveals their stories

1. The Sexual Etiquette Coach

One of Hollywood’s most unusual coaches was the English romantic novelist and script writer Elinor Glyn, sexual etiquette style guru to the stars. Her romantic novels were the early-20th-century version of Fifty Shades of Grey. They often featured voluptuous ladies reclining on tiger skins, giving rise to the ditty:

Would you like to sin / with Elinor Glyn / on a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer / to err with her /on some other fur?

One of Glyn’s most able pupils was the Italian-born heart-throb Rudolph Valentino. She taught him to kiss the open palm of his leading lady’s hand in the 1922 film adaptation of her book Beyond the Rocks. Apparently that one kiss caused women in movie theatres across the world to swoon. Strangely, Valentino was playing an English lord in the film, which was a departure from his usual role of Latin lover.

Having a Latin lover as male lead in a film was a guaranteed box office draw in the 1920s. There was even a set type of characteristics for such a leading man. He had to be handsome, with dark hair and a Mediterranean complexion. He had to have an air of mystery, a penetrating stare, a tendency to dramatic outbursts of passion and a fearless attitude to life.

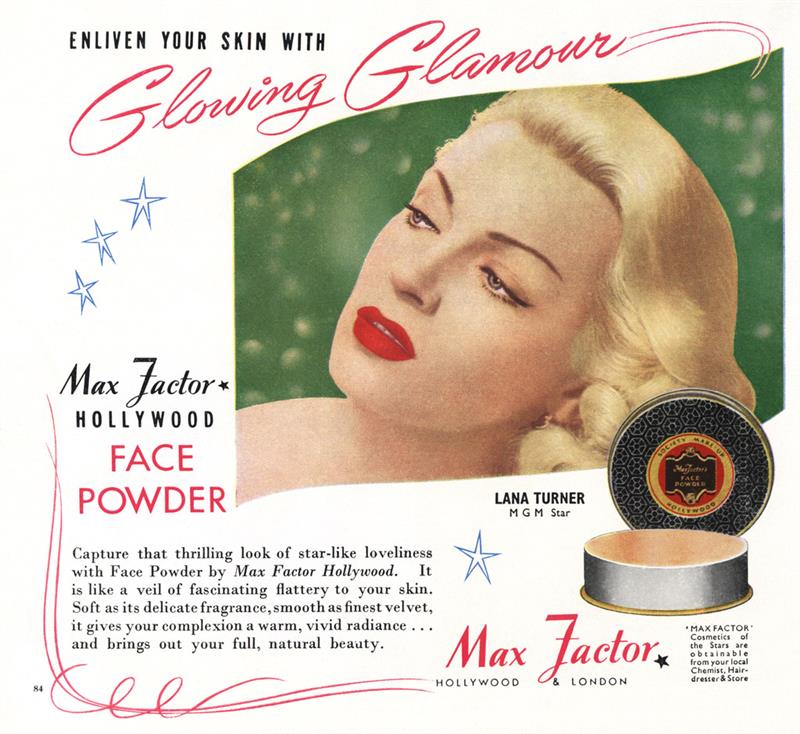

A poster for Max Factor make-up featuring Lana Turner

A poster for Max Factor make-up featuring Lana Turner

2. The Man Behind The Make Up

The only way Valentino was able to take on the role of the English lord was thanks to some skilful skin-lightening make-up, courtesy of a beautician and wigmaker called Maksymilian Faktorowicz. Born in 1872 in Lodz, Russia (now part of Poland), Faktorowicz would go on to become better known as Max Factor. He invented the word ‘make-up’ in 1920, and his work within Hollywood was core to creating the glamorous look the movie moguls were after.

Early silent movie actors and actresses had not only to deal with arc lighting, which caused severe conjunctivitis due to unshielded ultraviolet light, but also with the exposure that black and white orthochromatic film brought. It magnified the slightest imperfection and turned skin colour unnaturally dark on screen. The only way to combat this effect was to pile on thick white greasepaint and powder.

In response, Max Factor developed a new product called ‘Flexible Greasepaint’. This was the first make-up made specifically for motion pictures, and it was the first natural-looking cosmetic to be used in film production.

With the advent of talkies in the late 1920s, radical changes occurred in both the filming process and film make-up. Those arc lights were now too noisy for sound stages, so they were replaced with tungsten lights, which did not splutter and hiss and didn’t cause eye problems. But these lights were less bright, which made it necessary to change to a new type of black and white film called panchromatic, which would be sensitive to the softer tungsten lighting.

To cope with the softer lighting Max Factor introduced ‘Pancro’ make-up. This line of neutral-coloured greasepaints, powders, rouges, liners and pencils reflected the correct amount of light for the sensitive new film, and was not affected by the heat of tungsten lights. Later, in 1935, he created one of his greatest accomplishments, ‘Pan-Cake Make-up’, which was to be used with the new Technicolor film. Without any correcting cosmetics, actors’ faces appeared either red or blue, due to the nature of Technicolor. Pan-Cake restored the actor’s natural colour and allowed for well-defined facial features when viewed on screen.

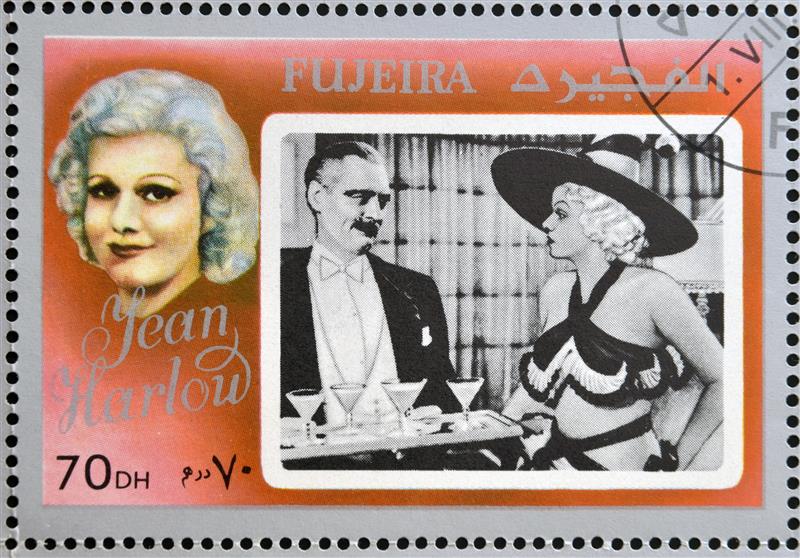

Such was Jean Harlow's fame, she even appeared on postage stamps (issued in Fujeira, c.1972)

Such was Jean Harlow's fame, she even appeared on postage stamps (issued in Fujeira, c.1972)

3. The Masters of Perfection

Max Factor’s make-up was just one element that helped actress Jean Harlow become a public idol. Another was her transformation from shy ash blonde to platinum bombshell – a hair colour achieved by bleaching with a weekly application of peroxide, ammonia, Clorox bleach and Lux soap flakes.

George Hurrell was the photographer who captured Jean Harlow’s allure and he was a master of Hollywood glamour photography. This he achieved not just by clever lighting, but also with artful retouching. Hurrell worked with a professional retoucher named James Sharp, who would spend six hours at a stretch using a pencil to smooth out the skin, remove spots and freckles and erase wrinkles. Sharp used a retoucher machine, which backlit and vibrated the original negative, allowing him to physically smooth out the film using the pencil.

4. The Dazzling Designer

In the 1930s historical movies became a favourite in Hollywood. Marie Antoinette, starring Norma Shearer and Tyrone Power, was made in 1938 by MGM and was one of the most expensive films of the era, with extravagant costumes and opulent sets.

The man responsible for the look was costume designer Gilbert Adrian. He scoured books on the period and based some of Shearer’s costumes on surviving portraits of Marie Antoinette, especially those by her favourite artist, Élisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, along with other artists of the period.

By the time he worked on the film, Adrian had already built his reputation as the leading designer in Hollywood. Copying his designs had become big business for fashion retailers, much to the delight of the film companies, who were able to promote their movies on the high street.

Adrian’s designs for Greta Garbo were especially popular and were regularly recreated by fashion houses. For the film Romance he designed a little velvet hat trimmed with ostrich feathers, to be worn tilted, becomingly, over one eye. It was based on a 19th-century riding hat, and named after the French empress Eugénie. This ‘Empress Eugénie’ hat became a fashion sensation after Garbo wore it with such panache.

Joan Crawford with glitzy jewellery, glinting in the camera lights

Joan Crawford with glitzy jewellery, glinting in the camera lights

5. The Jeweller To The Stars

Eugene Joseff was the man responsible for creating 90% of all the extraordinary costume jewellery in the movies of the golden era.

Jewellery had always been a problem for the wardrobe department. As the studio lights reflected so harshly off silver, gold and precious stones, it made them almost impossible to wear. Joseff had previously worked in a metal art foundry and he developed a matte metal finish for his jewellery, which he called ‘Russian Gold’. This minimised the glare from the studio lights. He also made it light to wear, even when the pieces appeared to be chunky and heavy.

He was able to recreate everything from royal treasures to contemporary designs for sumptuous earrings, necklaces and bracelets. But his forte was creating historically accurate pieces for period films such as The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex with Bette Davis.

Joseff became the premier costume jeweller in Hollywood, designing, manufacturing and rather cleverly renting, rather than selling, jewellery to movie studios, under the brand name Joseff of Hollywood. In the 1930s and 1940s, he was not only supplying most of the jewellery worn in films, but was also running a successful retail outlet in Hollywood, so people could buy copies of the same pieces they had seen worn by the stars.

His jewellery is now collectable. A pair of rhinestone earrings worn by Norma Shearer in Marie Antoinette sold a few years ago for $4,000; and an auction in 2017 saw prices for similar pieces of movie jewellery selling for as much as $90,000.

Geri's Top Tips

Books to read

For great behind-the-scenes stories in Hollywood, see these colourful books:

Max Factor’s Hollywood: Glamour, Movies, Make-up by Fred E Basten; Los Angeles: General Publishing Group.

Jewelry of the Stars: Creations from Joseff of Hollywood by Joanne Dubbs Ball; Pennsylvania, Schiffer Publishing

Hollywood Costume, edited by Deborah Nadoolman Landis; V&A Publishing

George Hurrell's Hollywood by Mark A Vieira; Running Press

Fabulous photos

If you love viewing the wonderful imagery of the stars of early Hollywood, but want to do so economically, here is a tip: in the 1970s and 1980s publishers competed to publish the ‘story’ of each Hollywood studio. Each volume was crammed with film stills. You can still buy them online, but do look in charity shops, where you can often pick up a second-hand copy for a song.

Discover film on the small screen

Documentaries about early Hollywood and some of the early movies themselves often appear on TV, but do also take a look at the BFI’s website, where you can rent documentaries and classic movies.

Where to see the real thing

The Hollywood Museum in the United States is the official museum of Hollywood and has the most extensive collection of memorabilia in the world. It’s housed in the original Max Factor building on Hollywood Boulevard.

The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum is home to one of the largest collections of material related to the moving image in Britain. You’ll find it at Exeter University.

The V&A Museum has over 3,500 stage costumes and accessories including film memorabilia.

The Cinema Museum in London houses a unique collection of artefacts, memorabilia and equipment that preserves the history and grandeur of cinema from the 1890s to the present day.

During this period of Covid-19, please check opening times when planning to visit.

Our Experts Story

Geri Parlby is a lecturer and writer. She started in journalism in the 1970s, before joining United International Pictures as head of press, working on films from Universal, Paramount, MGM and United Artists Studios. She retrained as an art historian in 2001, after studying at the Courtauld Institute. Among her lectures for The Arts Society are Magic Lanterns to Metro Goldwyn Mayer: the birth of the Silver Screen and the art that surrounded it and From Garbo to Garland: the magical art of Hollywood.

If You Enjoyed This Instant Expert Feature...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

About the Author

Geri Parlby

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition