This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on…the art and life of the brilliant Sir Henry Raeburn

Become an instant expert on…the art and life of the brilliant Sir Henry Raeburn

18 Jun 2024

Sir Henry Raeburn was the leading Scottish portraitist of his time, with a dazzling aptitude for capturing the character of his sitters. Our expert, Amanda Herries, is curator of a new show of works by the artist. Here she reveals the core facts about his life and portraits, which should, she says, be known far better

Sir Henry Raeburn’s Self-Portrait, c.1815. Image: purchased 1905; National Galleries of Scotland

Sir Henry Raeburn’s Self-Portrait, c.1815. Image: purchased 1905; National Galleries of Scotland

‘He is the last and greatest visual representative of the Scottish Enlightenment’ Historian and critic William Vaughan

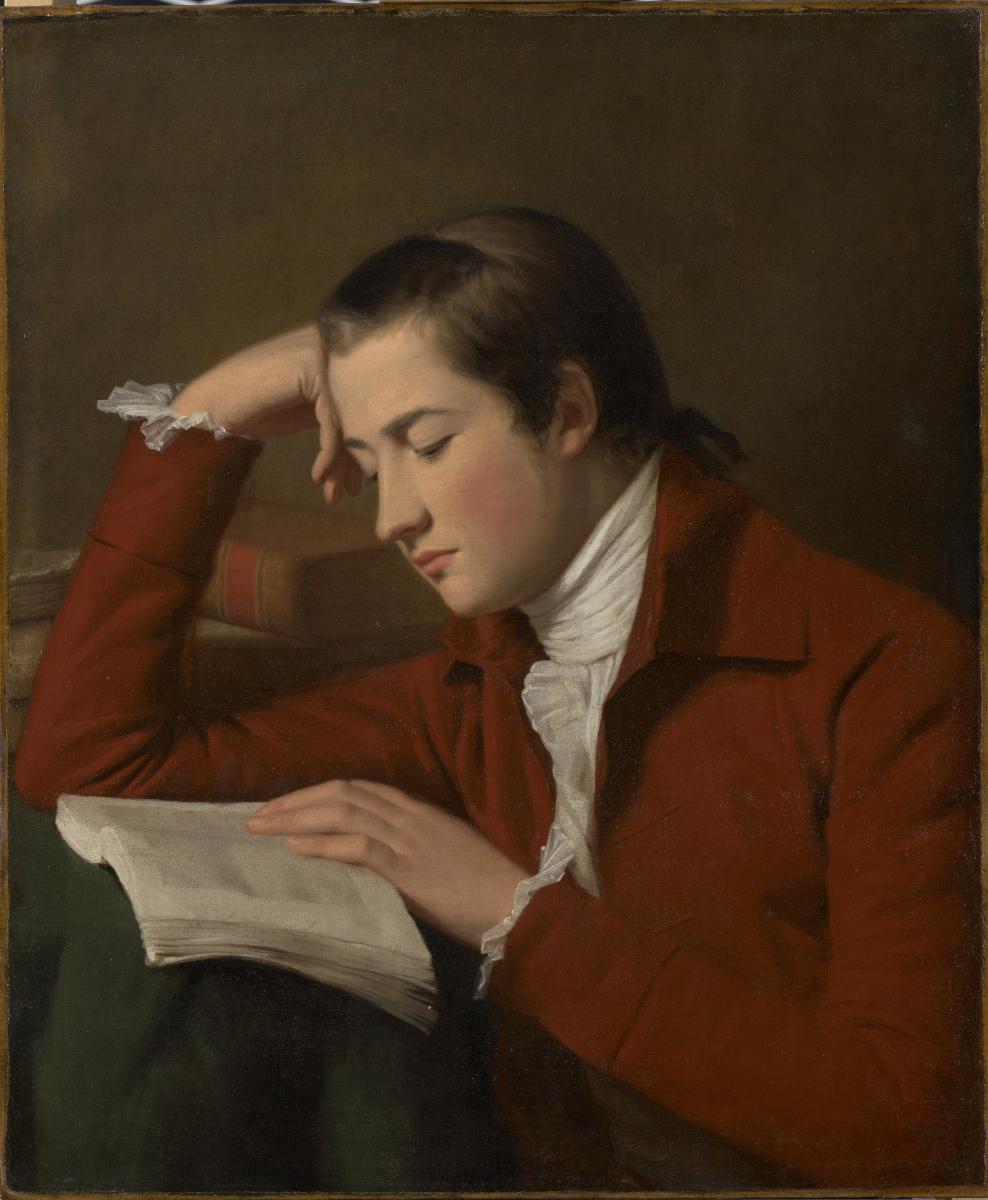

Patrick Moir, 1769–1810, c.1786. Image: purchased by Private Treaty with Art Fund support and funds from the Cowan Smith and Treaty of Union Bequests, 2023; National Galleries of Scotland

Patrick Moir, 1769–1810, c.1786. Image: purchased by Private Treaty with Art Fund support and funds from the Cowan Smith and Treaty of Union Bequests, 2023; National Galleries of Scotland

1. From orphan to painter

The turn of the 18th and 19th centuries is considered a golden age in British art: think of artists such as George Stubbs, John Constable and JMW Turner. The pantheon of portrait painters who also glittered at this time, basking in the admiration of a demanding London society, were many. Among them were Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Lawrence. Lawrence became London’s darling, with bravura full-length portraits being the forerunners of later 19th-century ‘swagger portraits’.

Some 400 miles north of London, in Scotland, another painter of remarkable talent was also at work. This artist, Henry Raeburn, was to easily earn his place among the greatest of British portrait painters.

Surprisingly little is known of this Scotsman, who was born in Edinburgh in 1756 and died there in 1823. Like Lawrence he appears to have been largely self-taught, but unlike Lawrence, who showed an aptitude for drawing from the age of 10, Raeburn’s development – and reputation – as a portrait painter didn’t emerge until his late 20s.

Born the son of a yarn boiler in the then village of Stockbridge, about a mile from the centre of Edinburgh, Raeburn was orphaned early. In 1772, aged 16, he was apprenticed to a jeweller and goldsmith in Edinburgh’s Old Town, and it’s thought he might have had some training in miniature painting. It’s also possible – but this is conjecture – that Raeburn attended classes with well-established artists in Edinburgh.

By 1780 Raeburn’s life had taken another turn. He had married a wealthy widow, Anne Leslie (née Edgar). Some 11 years older, she brought two daughters and property in Stockbridge to the marriage. By 1784 he was describing himself as ‘Portrait Painter in Edinburgh’ (yet almost no evidence of this survives). He travelled to London and then on to Italy – the well-worn artistic path to study the Old Masters.

Raeburn returned to Edinburgh in 1786 with surprisingly original skills and techniques, and significant mastery of portrait painting. We know little of his time in Rome: the tuition he might have had, the artists who could have influenced him, or the work he might have produced. Evidence from two small canvases shows him copying known Italian works.

Only one portrait is known – a remarkably sophisticated study of a young man, Patrick Moir, leaning on one elbow, completely absorbed in the book he is reading, seemingly oblivious to the artist studying him so acutely.

Reverend Robert Walker (1755–1808) Skating on Duddingston Loch, also known as The Skating Minister (1790s). Image: purchased 1949; Scottish National Gallery

Reverend Robert Walker (1755–1808) Skating on Duddingston Loch, also known as The Skating Minister (1790s). Image: purchased 1949; Scottish National Gallery

2. Talent and success

From beginnings of which we have such scant knowledge, Raeburn’s career flourished.

His talent is evident from works of the late 1780s onwards. Over a period of nearly 35 years he honed his craft and developed his techniques, quickly settling into the role of sought-after portrait painter. Remarkably, over 1,000 portraits by Raeburn have been identified, with no evidence that he had student help or any assistance in his studio.

Raeburn seems never to have deviated from portraits. Gainsborough, Reynolds and Lawrence were as prolific, but painted landscapes, or worked in pastel, chalk or pen. With a couple of exceptions from early years there is no example of a sketch or anything other than oils painted by Raeburn. In addition, his paintings are neither signed nor dated, which can present art historians with a challenge.

His output includes hundreds of single portraits at the cheapest portrait-size of canvas then available. There are also dozens of groups, often of children, or parent and child, on larger canvases. He also painted a considerable number of magnificent full-length portraits, usually of a single figure but very occasionally a double portrait. And finally, even though he’s not particularly known as a skilled painter of animals, we know of more than 20 majestic portraits of a man and horse.

There is one startling anomaly – and it is probably Raeburn’s most well-known painting. The Skating Minister now almost buckles under the weight of heavy promotion, merchandising and consequent celebrity. It is unique both in its small size (76 x 63cm) and the way in which its subject, Reverend Robert Walker, is portrayed – completely in profile and almost as silhouette.

John Robison (c.1798) by Sir Henry Raeburn. Image: © University of Edinburgh Art Collection

John Robison (c.1798) by Sir Henry Raeburn. Image: © University of Edinburgh Art Collection

3. How did he do it?

As stated, there is no evidence of sketches or indeed any sort of preparatory work for Raeburn’s portraits.

Several sitters described his way of working as what today would be called sight-size. This is when an artist draws an object exactly as it appears, on a one-to-one scale. In his studio at York Place in Edinburgh, Raeburn set up his easel close to the sitter who would be on a platform, standing or seated in a chair.

Raeburn would study his sitter carefully, walk away backwards to the end of his large studio, still observing, then consider, return, paint immediately and repeat.

He always started with the face, fixing the features in his mind’s eye, using his observational skills to accurately record what he saw physically, and to draw character out of that face.

The results are remarkable.

If possible, take a close look at one of Raeburn’s portraits and examine the range of brushstrokes. See the great precision in the details of the face, the tiniest dot of white to illuminate the eye, the smoothness to the skin. He used a ‘square brush’ technique, much favoured among Impressionists some 50 years later, for elements of clothing, such as cravats, bonnets, coats and dresses.

More often than not Raeburn’s portraits are set against an abstract background. These are sometimes refined but on occasion are created with an almost carelessly shaded palette, or a dark, determined intensity. The Royal Academy of Arts in London, of which Raeburn was made Associate in 1812 and full Member in 1815, disapproved of this technique, feeling he did not ‘finish’ his paintings in proper detail.

Yet Raeburn was all about detail.

He took his task of making a true record of his sitter seriously. He paid close attention to the face and demeanour of his client, with arresting results. He was intrigued by the balance of light and shade falling on a face and experimented with light – often with startling panache – throughout his career. He even designed a complicated shuttering system in his studio to play with the light, and he changed the size of the windows.

Sarah Wadsworth, later Mrs Robert Hartshorn Barber (1797–1873), c.1820. Image: courtesy of Philip Mould & Company, London

Sarah Wadsworth, later Mrs Robert Hartshorn Barber (1797–1873), c.1820. Image: courtesy of Philip Mould & Company, London

4. Who sat to Raeburn and why?

Having your portrait painted was important on all sorts of levels.

Historically, of course, it was the only way to record someone visually in colour. The practice was restricted, largely, to royalty, aristocracy and people (usually men) who had acquired high office or esteem.

As a visible record of someone’s existence, and with a history stretching back centuries, a portrait symbolised power and authority; such paintings were also deliberately decorative, as befitted their subjects. Along with the aristocracy, Raeburn’s clients included the military, judiciary and many of the thinkers, intellectuals and scientists of the Scottish Enlightenment, which coincided with his most prolific years.

By the 18th century portraiture had become a fashionable prerequisite. Increasingly it was one of the most ostentatious symbols of status among those who could afford it. These included the many highly successful middle-class clients who were making their money as Caribbean plantation owners, or who were in some way involved with the dominant and profitable trade in sugar and tobacco out of Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Additionally, Raeburn’s clients often had their wives, daughters and young children painted. These portraits were rarely exhibited in public, although they are a significant part of his output. Traditionally Raeburn’s reputation focuses on his portraits of men, but his paintings of women are, as seen here, just as – if not more – arresting but perhaps not quite as visible to critics.

Raeburn’s women don’t just represent, in vivid fashion, the dramatically changing fashions of the day – they are also works of great sensitivity, knowingness and allure. There is often an exquisite sense of a movement or a glance caught and suspended in these works, captured for ever on canvas.

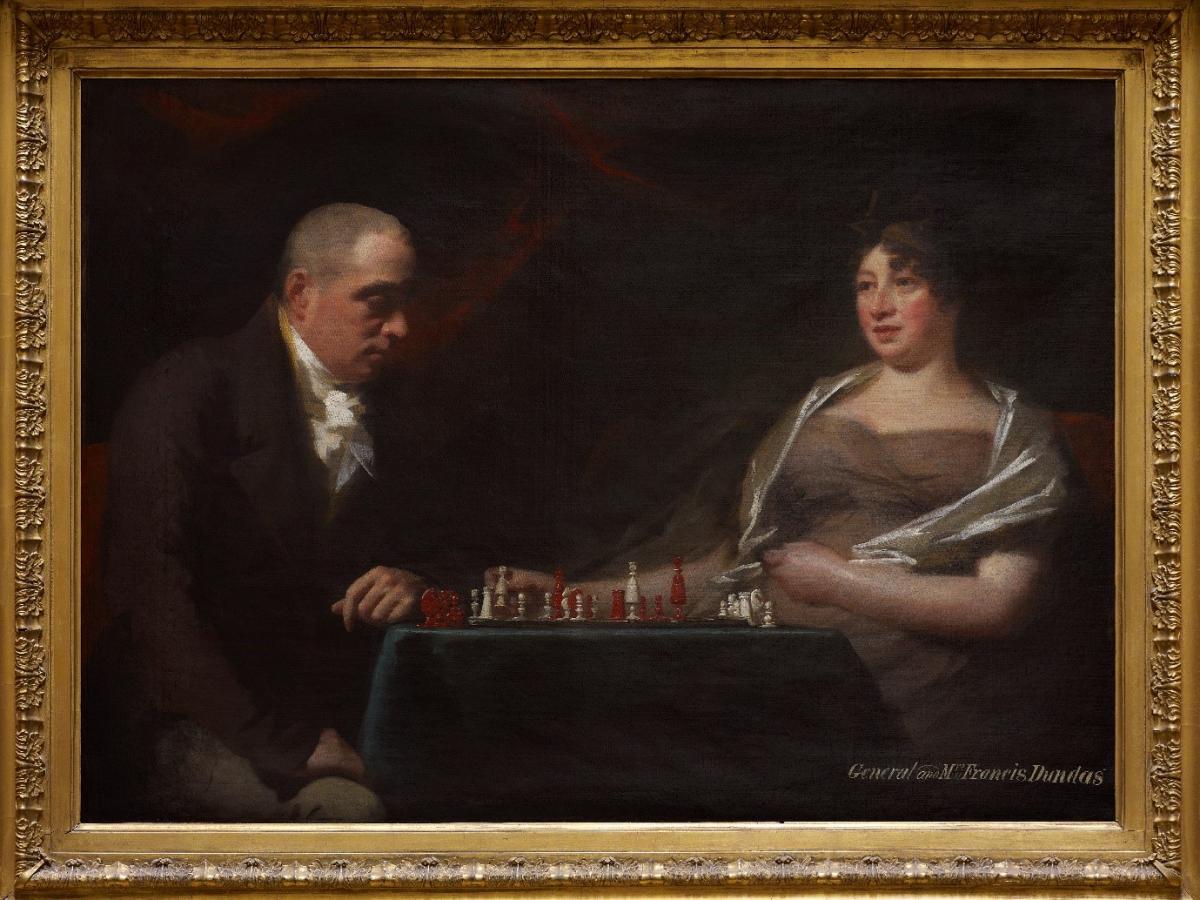

General Francis Dundas and Eliza Cumming, Mrs Francis Dundas, c.1812–15. Image: courtesy of the Arniston House Collection

General Francis Dundas and Eliza Cumming, Mrs Francis Dundas, c.1812–15. Image: courtesy of the Arniston House Collection

5. Fame and legacy

Among the hundreds of paintings of wealthy and aspirational Scottish sitters, Raeburn also painted a handful of radical portraits, focusing on light, shade and those single moments of movement.

This work above, of General Francis Dundas and his wife, Eliza, playing chess, is one of these. She is amused, he downcast. She is caught in the moment of checkmating her husband.

For the viewer this is an opportunity to see not only Raeburn’s skill as a portraitist but his aptitude for presenting the relationship between sitters as well. It also demonstrates his skill in structuring the image to capture a fleeting and intimate moment.

In such paintings Raeburn’s link with today’s photographic portraits is perhaps closest; the contemporary obsession with image and the ‘selfie’ has a direct correlation with Raeburn’s sitters and their desire for visual recognition.

In 1810 Raeburn, now at the height of his powers, was nearly lost to Scotland.

He considered moving to London after his son and son-in-law’s trading company, for which he stood guarantor, plunged him into bankruptcy in 1808. He knew he could almost double his fees in London, but he eventually remained in Edinburgh, painting, copying his own paintings and creating an extraordinary visual record of Scottish society at a seminal period in its history.

In 1822 he was knighted by George IV on his momentous visit to Scotland and was appointed the King’s Limner in Scotland. Less than a year later Raeburn died.

His reputation was enhanced in the decades after his death, culminating in a world-record auction price, in 1911, of any work by any artist. The auction was at Christie’s London, and the painting was his c.1823 portrait of Mrs Robertson Williamson, which went for a memorable price of 22,200 guineas. But fashions change. That painting went on to be sold several times and now languishes, cut down, in the store of the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. Henry Raeburn, Scotland’s foremost portrait painter, creator of such delightful and insightful works, deserves better recognition.

Amanda’s top tips

See

Eye to Eye: Sir Henry Raeburn’s Portraits

Kirkcudbright Galleries, Dumfries and Galloway;

29 June–29 September; entrance free;

Also see Raeburn’s works at:

Scottish National Galleries, Edinburgh

Holding some 30 paintings, the galleries have an impressive new hang of Raeburn’s works, including his Self-Portrait and The Skating Minister; nationalgalleries.org

National Trust for Scotland

You’ll find works by Raeburn at many properties; nts.org.uk/search

ArtUK website

This records some 391 portraits by Raeburn in public collections in the UK. Some are in storage, many are not; artuk.org

Good reads

Henry Raeburn, the Mirror of Scotland, by Amanda Herries. This book accompanies the exhibition; info@friendskg.org.uk

Raeburn – the art of Sir Henry Raeburn, 1756-1823, by Duncan Thomson with contributions from John Dick, David Mackie and Nicholas Phillipson; published by Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, 1997

Henry Raeburn: Context, Reception and Reputation, edited by Viccy Coltman and Stephen Lloyd, Edinburgh University Press, 2012

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

About the Author

Amanda Mason

With a degree in archaeology, Amanda was a curator at the Museum of London for a decade, specialising in the 18th to 20th centuries. She spent eight years in Japan studying East-West connections, and draws on this eclectic background for her lectures, writing and broadcasting. In addition, she has spent three years cataloguing Southern Scotland for the ArtUK project. Among her interests are decorative arts, including jewellery, porcelain and doll’s houses, social history and Oriental and Western cross-cultural and artistic influences. You can read her ‘Instant Expert’ on ‘The Japanese Garden, East and West’ here. Among her talks for The Arts Society are Skin Deep: the beastly art of beauty, Opium: seduction, greed and art, A study of Joan Eardley (a focus on the art of the Scottish artist who died in 1963) and East meets West: the influence of Chinese and Japanese art on European decoration. Look out, too, for her new lecture, The making of an exhibition: rabbits, rabbit holes and Henry Raeburn.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition