This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

In the ring with Francis Bacon

In the ring with Francis Bacon

27 Feb 2022

Curator Sarah Lea explains the story behind the making of Francis Bacon’s Study for Bullfight, No.1

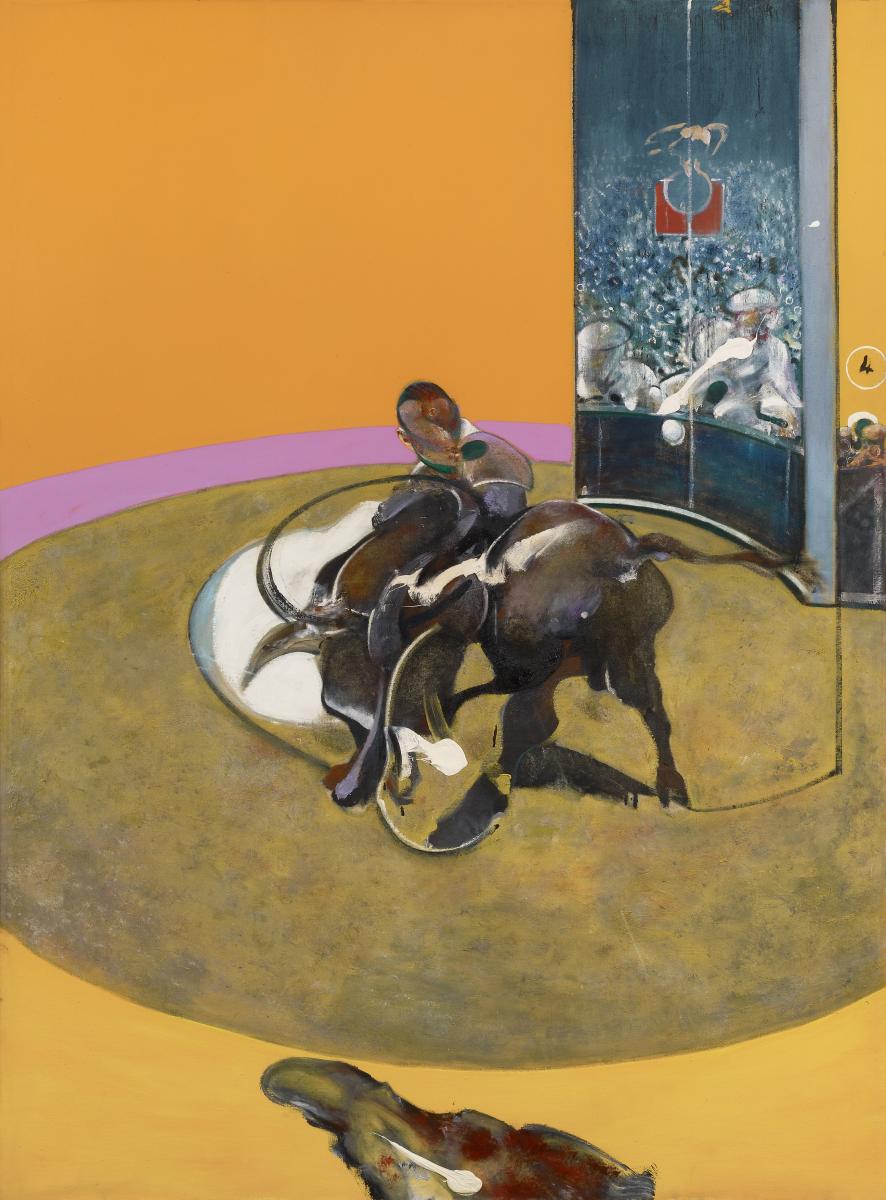

Francis Bacon, Study for Bullfight No. 1, 1969. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2021. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd

Francis Bacon (1909–92) was captivated by animals. Over his career he painted chimpanzees, elephants, owls, dogs, bulls and hybrid creatures inspired by stories from Ancient Greece and Egypt. He believed that the uninhibited behaviour of animals revealed primal drives and fears shared by humans. In his paintings he sought to pierce the veneer of civilisation to reveal raw and fundamental truths.

His 1969 oil on canvas, Study for Bullfight, No.1, is a tour de force, exploring the human instincts for power, danger, excitement and survival. Bacon’s three bullfight paintings are exhibited together for the first time at the Royal Academy of Arts in a new show.

1. TRIO OF ART

Three versions of this painting exist today, perhaps reflecting the three tercios, or stages, of the bullfight. If Bacon initially planned them as a triptych (a favoured format for his later works), he left it incomplete. The panels were dispersed during his lifetime and he destroyed a fourth version, possibly a new attempt at a central panel – an act he often undertook for works he was dissatisfied with.

2. MAN, BEAST AND MOVEMENT

The bullfight pits man against beast, yet the swirling mass of intersecting curves challenges the distinction between human and animal. When making this work, Bacon drew upon memories and adapted photographs that captured the dance-like motion of the bullfight in blurs, seen in the painting as gestural sweeps of rich brown, ochre, purple and black.

3. PROVOCATIVE NATURE

‘Bullfighting,’ Bacon once said, ‘is like boxing – a marvellous aperitif to sex.’ His provocative humour admits close links between violence, voyeurism and eroticism. He relished a febrile atmosphere and found it illogical that people who condemned the cruelty of bullfighting might still wear furs and feathers, or eat meat. The form in the foreground might be a bloodstain, a shadow or even a cut of meat.

4. ONLOOKING CROWD

A crucial element of this work is the faceless crowd that witnesses the drama of the bullfight, and mirrors our position as viewers of the painting. A red banner with the hint of an eagle recalls the imagery of both Nazi propaganda and the Roman Empire, raising disturbing questions about the complex relationships between spectacle, terror and power, and the capacity of the individual to become lost in herd mentality.

5. ‘CALCULATED RECKLESSNESS’

Lucien Freud’s summary, above, of Bacon’s approach to life also describes the risks Bacon took when painting. Here, white paint has been flung at great velocity at the canvas. This ‘accidental’ effect enhances the dynamism of the composition, but belies its precisely calibrated, artificial structure. The bull is vast compared to the circular arena, which is more the scale of an ordinary room, while the crowd appears in a strange, curved segment that is part screen, part window.

SEE

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Royal Academy of Arts, London; until 17 April

royalacademy.org.uk

SUBSCRIBE

This feature first appeared in the Spring 2022 edition of The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to Members and Supporters

About the Author

Sarah Lea

Sarah Lea is an art historian and co-curator of Francis Bacon: Man and Beast

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition