This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

PETER THE GREAT AND HIS RADICAL REFORMS

PETER THE GREAT AND HIS RADICAL REFORMS

15 Feb 2022

This year marks the 350th anniversary of the birth of that giant figure in the history of Russia: Peter the Great. Our expert, Rosamund Bartlett, reveals what Peter did for Russian art and culture – and why his approach included a tax on beards

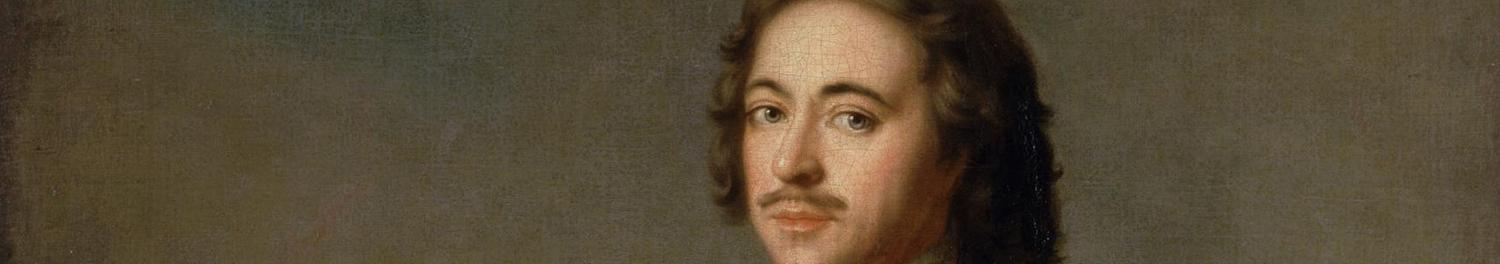

Peter the Great (1672–1725), a portrait attributed to Jean-Marc Nattier

Peter the Great (1672–1725), a portrait attributed to Jean-Marc Nattier

‘All Russia is your statue, transformed by you with skilful craftsmanship’

The leading theologian, writer and philosopher Feofan Prokopovich, writing about Peter the Great in 1726

1. REBEL ROMANOV

Peter the Great was Russia's first revolutionary.

Born in 1672, in a country on the edge of Europe that had experienced two and a half centuries of Mongol domination but neither the Renaissance nor any kind of Reformation, he grew up in a pious world shaped by the strictures of the Orthodox Church.

To its few foreign visitors, late 17th-century Moscow appeared both exotic and barbaric. Noblewomen lived in oriental seclusion. Wandering minstrels with tambourines were outlawed. The one living portrait of Peter's father, Tsar Alexei, only appeared in miniature at the bottom of an icon.

But by the time of his death in 1725, Peter had transformed Russia into a great military power, crowned a commoner as his empress, and succeeded in creating a glittering citadel of European culture in his new capital of St Petersburg. The Church was now subservient to the state, rather than the other way around, and society now allowed men and women of the Russian nobility to mingle at parties.

Peter began to challenge convention upon assuming power in 1689 at the age of 17. After the death of his mother, five years later, he simply stopped observing the Church fasts, turned his back on the ornate Byzantine-inspired rituals of the Russian court in the Kremlin, and scandalously refused to follow the time-honoured Orthodox tradition of growing a beard, so to resemble Jesus Christ.

He was also the first tsar to go to sea, setting sail from the port of Archangel on a Dutch ship. His victory against the Ottomans in 1696 was celebrated with a triumphal procession into Moscow, with pageantry which iconoclastically took its inspiration from imperial Rome.

An engraving of a portrait of Peter the Great by Dutch artist Carel de Moor

An engraving of a portrait of Peter the Great by Dutch artist Carel de Moor

2. PORTRAITS AND POWER

In March 1697, with the aim of fortifying his new alliance with Western powers against the Turks, Peter became the first tsar to travel abroad. While members of his entourage engaged in diplomacy, he studied shipbuilding, his incognito guise as a soldier complicated by the fact that he was nearly seven feet tall.

Instantly entranced with the trappings of European culture and society, Peter bought his first paintings and invited artists to Russia. During his time in Amsterdam he studied etching with Adrian Schoonebeck, and two years later despatched the young Aleksei Zubov from Moscow to become Schoonebeck's apprentice. Later to become Russia's first serious graphic artist, Zubov would engrave important early panoramas of St Petersburg for distribution abroad as advertisements of Russia's achievements.

Peter also became the first tsar to have his portrait painted. In London, when he was not visiting the Greenwich Observatory, attending a Quaker meeting or having rowdy, drunken parties in Deptford, he posed for Sir Godfrey Kneller, who depicted the confident young monarch standing in full armour with an ermine cape around his shoulders. Dozens of head and shoulders miniatures were swiftly produced to serve as calling cards.

In the summer of 1698 Peter was obliged to cut short his ‘Grand Embassy’, stopping only briefly in Vienna before returning home to quell a revolt.

The day after his arrival in Moscow he proceeded personally to shave the beards of his boyars, later imposing a notorious tax on all those who chose to adhere to the old patriarchal ways. Conservative forces loyal to old Muscovy and the Church began denouncing Peter as the Antichrist.

The soaring spire of Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, still one of St Petersburg’s main landmarks

The soaring spire of Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, still one of St Petersburg’s main landmarks

3. PETER'S PARADISE

At the start of the century Peter began his programme of reform in earnest.

He adopted the Julian calendar, so that each year began in January, rather than September.

He decreed that the gentry should exchange their kaftans for Western dress.

Women were shocked at having to uncover their hair, and the Church was scandalised when Peter did not appoint a successor when Patriarch Adrian died in 1700.

Uncompromising in his determination to break with the past and establish Russia as a modern maritime power, he also declared war on Sweden.

By 1703 he had acquired access to the Baltic and founded St Petersburg on the banks of the River Neva as his ‘window on Europe’. Domenico Trezzini was the first of a string of Swiss, Italian, Dutch, German and French architects invited to come and create a city on the inhospitable expanse of flat, empty marshland that Peter had conquered.

The tsar was a practical man of action with apparently little taste for ostentation, as exemplified by the modest dwellings built for him to live in, but from the outset he wanted the city he called his ‘paradise’ to be grand and beautiful, and he summoned gardeners to plant trees and scented shrubs.

It was after Peter's great victory over the Swedes at the Ukrainian city of Poltava in 1709 that the construction of his new city began in earnest. The Lutheran-style Baroque architecture of the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul set the tone for the revolution that followed. Its tall golden spire flouted centuries of onion domes and inaugurated his radically different vision of Russia as a progressive European nation.

Peter involved himself in each new architectural project, and in the planning of the city along rational, symmetrical lines, including the laying of a long, straight central avenue leading from his Admiralty.

Peter’s lavish Peterhof Palace, inspired by his visit to Versailles

Peter’s lavish Peterhof Palace, inspired by his visit to Versailles

4. RUSSIAN PYGMALION

Nine years after its foundation, Peter made St Petersburg his new capital, and he ordered his recalcitrant nobility to move from Moscow en masse.

Henceforth projecting himself as a Western absolutist monarch – with his features embedded in allegorical representations of the Roman god Mars, rather than his patron saints – he now turned his attention to fine arts.

This was a process that intensified after his lengthy second tour abroad in 1716, when he recruited painters and architects to come and work in St Petersburg. Former icon painters and craftsmen were brought to St Petersburg from the Kremlin Armoury to train with them, or were sent to study in Italy and the Netherlands.

In Paris Peter was feted with trips to the Louvre and boat rides down the Seine, while a visit to Versailles made an indelible impression and provided the blueprint for his sumptuous Peterhof Palace on the Gulf of Finland. Its initial architect, Jean-Baptiste Le Blond, left his stamp on its elegant terraced gardens and fountains.

Peter cultivated his image as a Pygmalion figure sculpting Russia – which was to be his Galatea. The Church decried works of art in three dimensions as graven images, but Peter filled his Summer Garden with classical statues, including the famed Tauride Venus, brought from Rome in 1718 after a deal was struck with Pope Clement XI.

Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli produced a bronze bust of Peter, and laid the ground for his son, Francesco, to become the high-profile architect of the Winter Palace. Lingering religious qualms, however, meant that the first public monument in Russia, Etienne Falconet's equestrian statue of Peter, The Bronze Horseman, commissioned by the tsar's self-styled ‘spiritual daughter’ Catherine the Great, was only unveiled in 1782.

A portrait medallion of Peter the Great and his family, by the first Russian painter of portrait miniatures Gregory Musikiiskii c.1716–7

A portrait medallion of Peter the Great and his family, by the first Russian painter of portrait miniatures Gregory Musikiiskii c.1716–7

5. LEARNING THE ART OF DECORUM

Although Peter had forced his nobility to dress like Europeans and relocate to St Petersburg, he felt they still needed instruction on how to behave in society.

In 1717 he ordered the publication of a compendium of European rules of comportment, which contained such helpful injunctions as: ‘don’t gorge like a pig; don’t clean your teeth with a knife; don’t hold bread to your chest while cutting it’.

The book was reprinted multiple times, which itself was something unprecedented: Dutch, Swedish and German artisans had helped establish mills in Russia, so paper no longer needed to be imported at great cost. A total of 500 books were printed before Peter became tsar, most of them ecclesiastical, compared to 1,200 during the 36 years of his reign, three-quarters of them secular.

The latter deployed the modern typeface created to accommodate the deluge of new Latinate words reflecting the expansion of Russia's horizons, from ‘arkhitektura’ to ‘balet’, ‘kravat’ to ‘vino’. Similarly, Peter called his country's first museum the Kunstkamera or ‘Art Chamber’ (from the German ‘Kunstkammer’), as there simply was no word for such a place in Russian.

In 1718 Peter issued a Decree on Assemblies (from the French ‘assemblée’), which set out rules for elite social gatherings and brought women into the public gaze for the first time. Dignitaries were obliged to host at least one assembly a year, and provide dancing, music and card-playing, as well as refreshments.

Peter's drastic westernisation programme changed the course of Russian history and laid the foundation for secular culture to flourish. His reforms did not extend to the enserfed peasantry, however, which inevitably led to a crisis of identity among the educated class. A heated debate over the issue of Russia's true destiny resonated across all the arts over the course of the 19th century, particularly in the great searching novels of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. That debate remains unresolved today.

ROSAMUND'S TOP TIPS

Follow in Peter’s footsteps

When restrictions allow, the best place to start exploring is St Petersburg. There you can visit the wooden Cabin of Peter the Great, where the tsar first lived when the city was founded; his modest Summer Palace on the Fontanka River; and the relatively unknown Winter Palace of Peter the Great, which forms part of The Hermitage Museum. On a summer's day, travel by hydrofoil to visit the palace and gardens at Peterhof outside the city.

Not so far to travel is Zaandam, north of Amsterdam, where you can step inside the Czaar Peterhuisje, the tiny 17th-century Tsar Peter House, where Peter stayed during his Grand Embassy in 1697.

Even closer to home, one can trace Peter the Great's steps in London by consulting Dr Sarah J Young's helpful web page: ‘Russians in London: Peter the Great’.

Good reads

Peter the Great: A Biography – the definitive account by the distinguished British historian of Russia Lindsey Hughes; Yale University Press, 2002

The Revolution of Peter the Great – a useful, condensed version of three volumes surveying Peter's reform of Russian culture and society, by James Cracraft; Harvard University Press, 2003

A Concise History of Russia – a work that places Peter's reign in succinct perspective, by Paul Bushkovitch; Cambridge University Press, 2011

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT EMAIL...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

Show me another Instant Expert story

Images: Paul Delaroche's portrait of Peter the Great © Bridgeman Images; Peter the Great monument, Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Peterhof Palace © Shutterstock; Gregory Musikiiskii's portrait medallion © Wikimedia Commons.

About the Author

Rosamund Bartlett

Rosamund Bartlett is a cultural historian of Russia with a doctorate from Oxford, who combines expertise in art, music and literature. She has lectured worldwide, contributed to Proms events and opera broadcasts on the BBC, and written for many of Britain’s top cultural institutions. A biographer of Chekhov and Tolstoy, she has also translated their works, including Anna Karenina for Oxford World's Classics. For further details, see: rosamundbartlett.com. Among her lectures are Russia's Window On Europe: the Architecture of St Petersburg, The Romanovs: the Public and Private Lives of Russian Royalty, and Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition