This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Drawn to the light

Drawn to the light

17 Jan 2022

A winter’s evening walk brings glimpses of a motif that, for artists, conjures homecomings, hauntings, nostalgia and desire. Peter Davidson explores the enduring fascination of the lighted window.

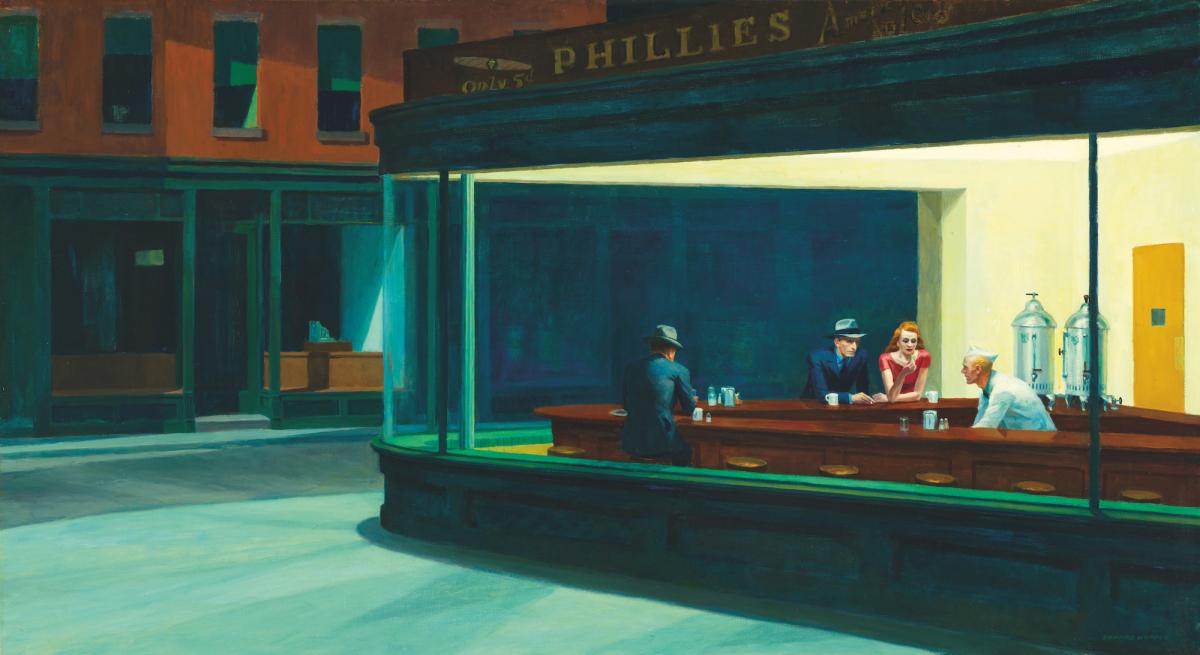

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942. © Art Institute of Chicago/ Friends of American Art Collection/ Bridgeman Images

It is evening now and I should walk home. This sentence opens a world of evening strolls and lighted windows seen and remembered. A walk past city windows is an imaginative journey through constellations of unknowable lives. Such walks bring recollections of artworks in all media; works that use the potent motif of the lighted window.

Innumerable examples of visual art focus on the window lit from within, particularly from the early 19th century to the present; and there are multiple literary treatments of the theme in the same period. In music, serenades imply a figure in a dark street, addressing the beloved at a lighted window.

This finds memorable form in Joseph Losey’s 1979 film of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, where the Don serenades Donna Elvira’s maid. This scene was filmed below a wing of the Villa Valmarana in Vicenza, so the artist Tiepolo’s beautifully sparse chinoiserie decoration is visible inside the frame of the window, lit from within.

Atkinson Grimshaw, Under the Moonbeams, 1887. Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images; Anton Prock

Lighted windows convey moods and meanings. In Victorian England, for the poet Matthew Arnold or the painter Atkinson Grimshaw, they can express the melancholy of the long 19th century. They conjure gaslight or lamplight glimmering on rain- wet cobbles, where a lonely, belated figure looks up at the lighted windows of gritstone suburban mansions, or a chapel in misted dusk. Late arrival, changed places, exclusion from present comfort and the lost happiness of the past are all here.

This tradition might be said to cumulate in the beauty, power, nostalgia and desire expressed by Alan Hollinghurst’s novel The Sparsholt Affair, as it moves through 20th-century history, tracing the fortunes of the handsome athlete first glimpsed in its pages in ‘that brief time between sunset and the blackout’ through a window in wartime Oxford.

‘THE LIGHTED WINDOW CAN REPRESENT THE SECURITY OF HOME,

A PROMISE OF DOMESTIC HAPPINESS, TOWARDS WHICH THE TRAVELLER HASTENS’

The glowing window in a quiet street or an isolated villa is also associated with the supernatural. The unexpected glimpse of a painted room or ceiling from the past can feel like a kind of haunting. Lamplight moving in an empty dwelling has become a cliché of ghostly tales. From the mysterious to the romantic, the potential of the lighted window is first explored in detail by Romantic painters working in Dresden in the early 19th century, particularly Caspar David Friedrich. In the UK, an intensely potent British image continuing the theme of moon and window light is found in Humphrey Repton’s delightful drawing of his proposed Gothic bower for a mansion on the shore of the Menai Strait, with the mountains of Wales rising beyond the water.

Interior of a Tyrolean church

The motif of the lighted window, indeed the work of art as lighted window, is seen in those optical devices – transparencies and backlit glass paintings – that painters have delighted in since the 18th century. These fascinated artists such as Thomas Gainsborough and Friedrich. The tradition continues today in temporary sacred theatres of Baroque elaboration, erected in Tyrolean churches at Easter, with effects of backlighting, varnished or pricked-through transparencies, and lights seen behind globes of coloured glass.

There is a fascination, too, associated with the lighted windows of great cities, particularly in the fictions of detection and adventure, which shape imaginations of the modern metropolis. Think of the canon of Sherlock Holmes stories and that of Father Brown. The approach of the London evening also brings forth a kind of lonely poetry, first observed in the fin-de-siècle nocturnes of James Whistler.

‘THE CHEMIST’S SHOP, WITH ITS BACKLIT FLAGONS OF COLOURED WATERS, HAS SOMETHING OF THE FLEETING SADNESS OF A DESERTED FAIRGROUND’

In turn, London windows, and the lives behind them, are perfectly observed by Virginia Woolf in her 1925 novel Mrs Dalloway, which concludes with one of the most beautifully realised evening glimpses through a London window in all fiction:

‘...it was also windows lit up, a piano, a gramophone sounding; a sense of pleasure-making hidden, but now and again emerging when, through the uncurtained window, the window left open, one saw parties sitting over tables, young people slowly circling, conversations between men and women, maids idly looking out... Absorbing, mysterious, of infinite richness, this life.’

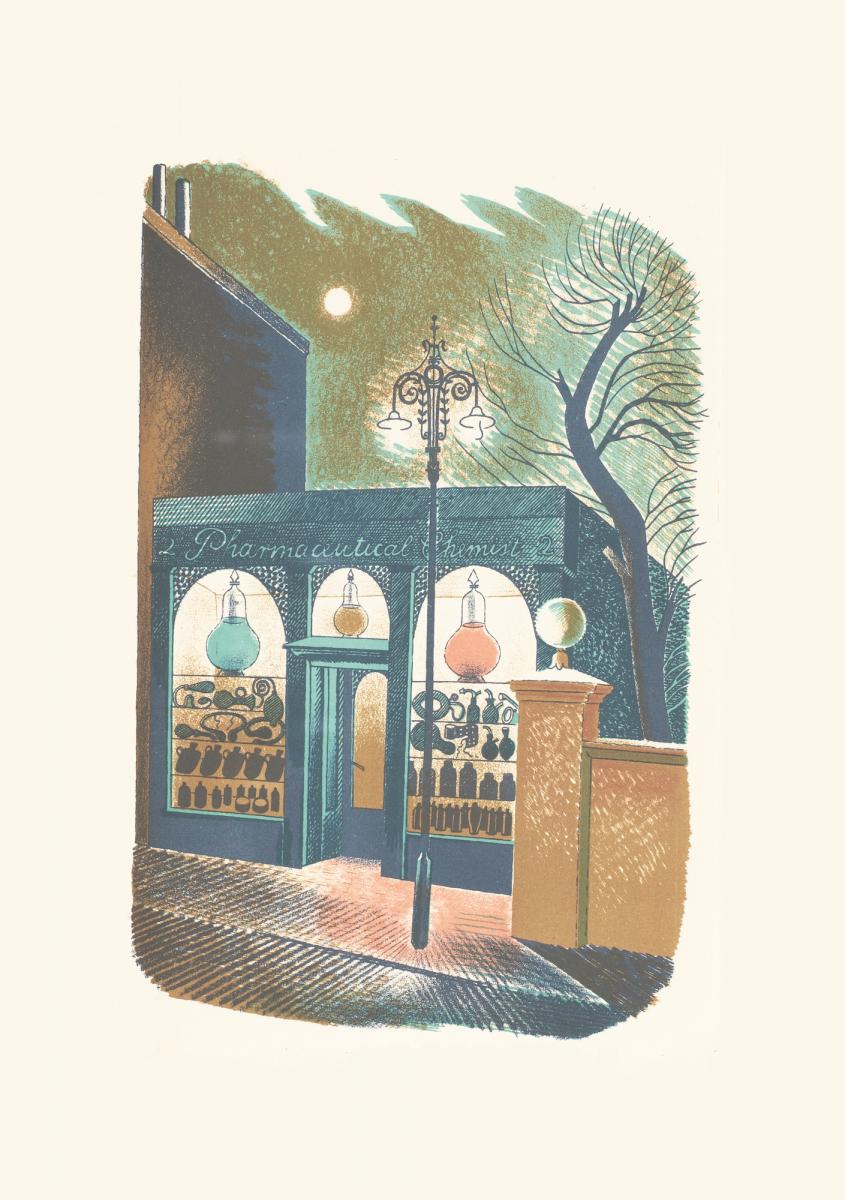

Eric Ravilious, chemist’s shop from High Street, 1938. Bodleian Libraries

Thirteen years later, in 1938, Eric Ravilious published his coloured lithographs of lighted shops and pubs in the book High Street. The work has a haunting quality, showing shops at night in deserted streets with an element of quiet strangeness. His chemist’s shop, with its backlit flagons of coloured waters, has something of the fleeting sadness of a deserted fairground, with wintery trees and moonlit sky showing above its roof. Yet the lighted window can also represent warmth, the security of home, a promise of domestic happiness towards which the traveller hastens at nightfall.

One of the most distinguished artists in this mode is Samuel Palmer. His gouache The Lonely Tower (also rendered in etching) occupies layered times and places. It is at once 19th-century England and Virgil’s pastoral Italy, with its star-surrounded, lighted tower window high above the gentle landscape.

Richard Bergh, The Fortress of Varberg, 1894. © Erik Cornelius/ National Museum 2008

The image of yellow, welcoming light in the vast blue dark of winter, such as that seen in Richard Bergh’s 1894 The Fortress of Varberg, is also a motif of Scandinavian romantic painting. The sheer scale of the northern landscape is emphasised by the sparse lights of the dwellings scattered across hills and islands. Much the same applies to the exquisite urban and rural nocturnes of 20th-century Japanese woodblock prints. In a very different mood, lit windows in darkness became a defining motif of American art in the years after World War II, and remain so in the work of contemporary American photographers, such as the makers of sad and disquieted photographic nocturnes, Todd Hido and Gregory Crewdson.

These artists of the lonely night hours are the heirs of Edward Hopper, whose paintings derive much of their power from the skilled placing of the imagined spectator as someone out too late, themselves transient and ill at ease. There is so much for the walker at evening to see and remember. A world is opened by that sentence: it is evening now and I should walk home.

FIND OUT MORE

The Lighted Window: Evening Walks Remembered by Peter Davidson

Published by Bodleian Library Publishing; bodleianshop.co.uk

This feature first appeared in the winter 2021 edition of The Arts Society Magazine, available exclusively to Members and Supporters

About the Author

Peter Davidson

Peter Davidson is Senior Research Fellow of Campion Hall, University of Oxford. His previous books include The Idea of North (2005) and The Last of the Light (2015).

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition