This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the World of Icons

Become an Instant Expert on the World of Icons

8 Nov 2021

The term ‘icon’ comes from the Greek ‘eikon’, meaning ‘image’. These objects of veneration come with a rich history, with the earliest surviving examples dating to the 6th or 7th century. Our expert, Helen McIldowie-Jenkins, unpicks the tale of the origins and making of this particularly singular art form

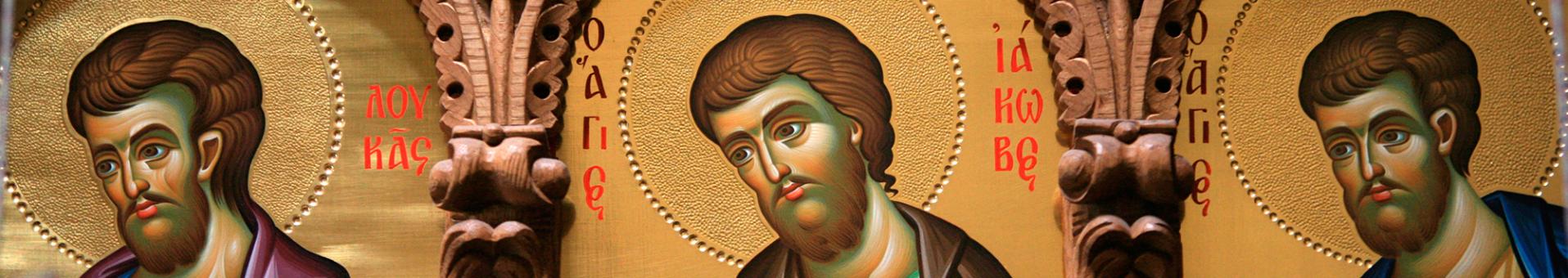

Icons at Agiou Pavlou monastery, Mount Athos in Greece

Icons at Agiou Pavlou monastery, Mount Athos in Greece

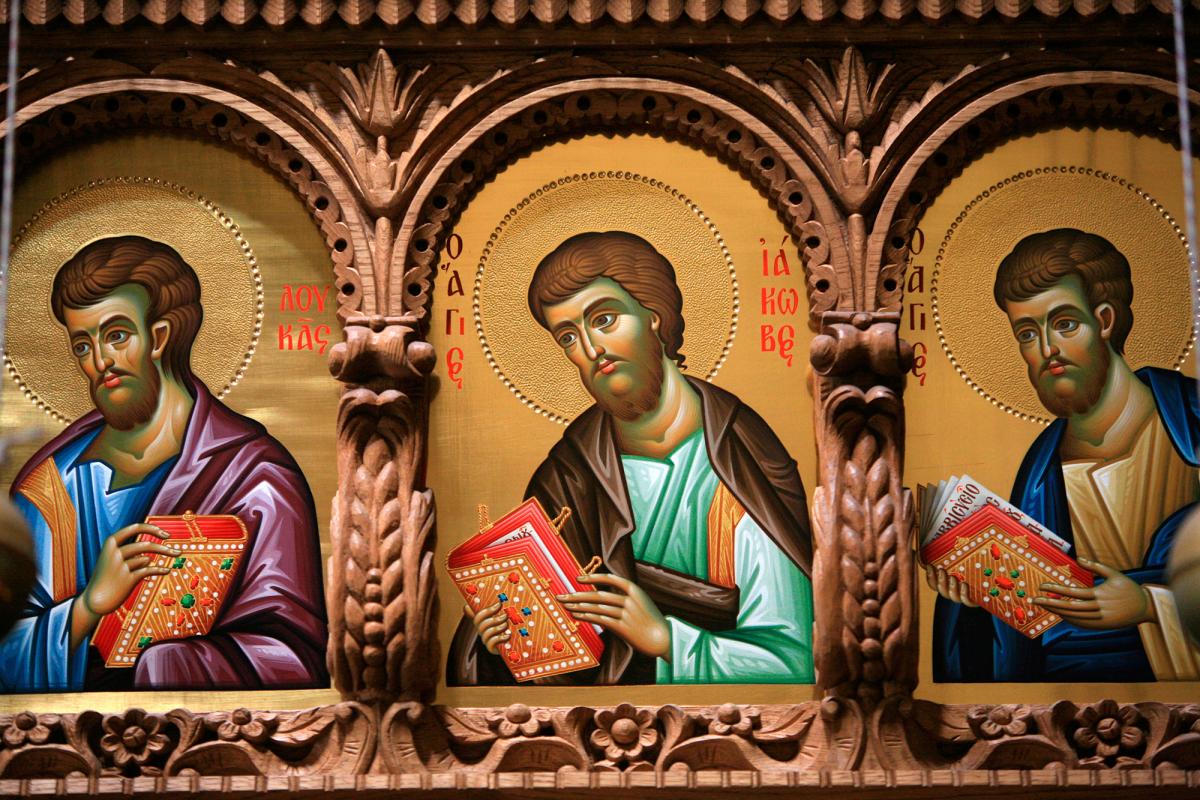

Detail of the Lamenting Virgin, The Crucifixion, from the 13th century

Detail of the Lamenting Virgin, The Crucifixion, from the 13th century

1. PIGMENTS OF THE IMAGINATION

First, a little introduction to our subject. Praying with icons is integral to an Orthodox Christian’s life. It is assumed that icons are ‘painted with prayer’ and, given their function to glorify God, faith and piety are expected of an iconographer.

Before commencing work, modern icon painters may use a variant of a prayer derived from a post-Byzantine painting manual by Dionysius of Fourna (c.1730–34), which petitions God for enlightenment, grace and wisdom to ‘direct’ their work.

Exactly how ancient iconographers approached their work is unknown, but coming from the silence-loving Hesychast tradition, silent, interior prayer was – and still is – the ideal. For this reason, the mantra-like ‘Jesus Prayer’ from the Russian contemplative tradition has become attached to icon painting. In practice, those engrossed in the act of painting are deep in right-brain activity and so would struggle to continually recite any set prayers.

One of the elements taking their focus will be that of colour.

The symbolic use of colour in Eastern Orthodox icons is not unique. What differs is the use of gold and certain pigments for phenomenological and symbolic effect, to reflect and radiate transfiguring ‘uncreated’ light – hence the use of gilded backgrounds, haloes and surface patterns.

The radiant power of vermilion red perfectly conveys concepts of divine energy and life. The garments of Christ – in dynamic red and luminous mystical blue – represent his human and divine natures. The same duo of costly colours denotes the fiery red cherubim and heavenly blue seraphim. Pure white, although luminous, is reserved mainly for the robes of the transfigured and resurrected Christ.

Generalised guidelines for the colour schemes for saints’ garments were listed in 16th- to 17th-century Russian icon pattern books (podlinniki). For example, the Stroganov and Bolshakov podlinniki state (without explaining why) that Mary Magdalene’s cloak should be in a pale green (praselen) and her under-tunic, ochre (vokhra).

The Mother of God is invariably depicted wearing a deep-red robe, a colour symbolising her human participation in the incarnation, but exceptions can be found, especially in her role as the ‘Seat of Wisdom’ or the ‘Lamenting Virgin’, where she wears blue robes to emphasise her divine status.

Detail of The Burning Bush, an icon of the 17th century, the Volga region

Detail of The Burning Bush, an icon of the 17th century, the Volga region

2. SEEING STARS

There are hundreds of variants of ‘Mother of God’ icons, each developed from an ancient archetype – with a specific scriptural, liturgical meaning – overlaid with apocryphal, local and historic narratives.

The main categories are the ‘Enthroned Virgin’ (with Christ Emmanuel on her lap), which was inherited from late Roman imagery, and the formal Byzantine ‘She Who Shows the Way’, the classic ‘Mother and Child’ image.

From this developed the more intimate ‘Virgin of Tenderness’ model, distinguished by the close embrace of mother and child, their faces touching. The visionary ‘Virgin of the Sign’ image shows her with arms raised in prayer, often bearing an antique-style roundel of the Christ child she will conceive. When depicted standing to the left of Christ, her head inclined and hands extended, she is the ‘Virgin of Intercession’.

All these images show three small stars on the head and shoulders of the Virgin’s robe (certain poses restrict this to two stars). This star rating symbolises Mary’s ‘Perpetual Virginity’ before, during and after the birth of Christ, according to apocryphal tradition.

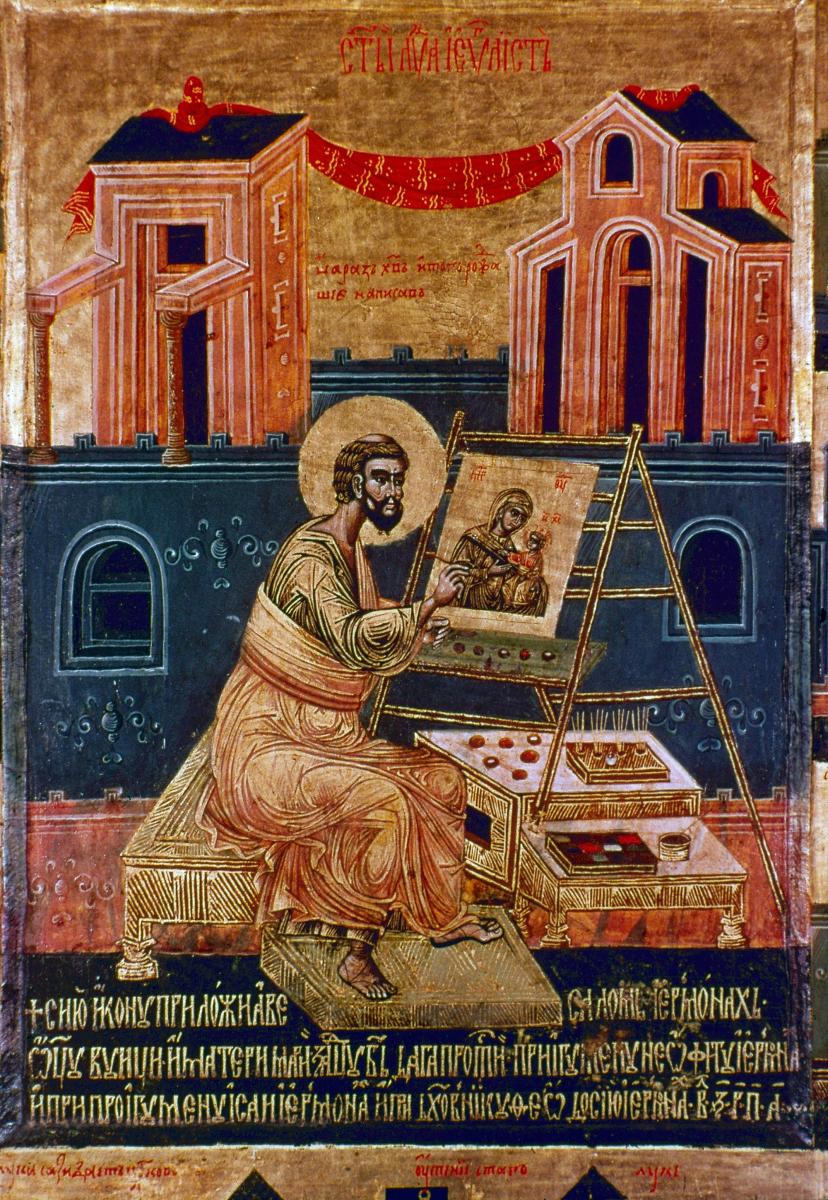

Because the Virgin remains intact, Orthodoxy likens her to the Burning Bush of the Old Testament, another ‘unburnt’ container of God. This analogy is fabulously symbolised in Russian icons of ‘The Virgin of the Burning Bush’, where in the midst of a red and green mandala-like star of ‘fire’ and ‘bush’, she presides over the angels of the Apocalypse, prophets, evangelists and the angelic powers who govern the natural world.

Detail of Christ in Majesty, from the second half of the 16th century, from the Byzantine Museum, Zante

Detail of Christ in Majesty, from the second half of the 16th century, from the Byzantine Museum, Zante

3. INSCRIPTIONS: IT'S ALL GREEK TO ME

The icon is a formulaic image with standardised inscriptions, which are usually abbreviated and should be regarded as more of a doctrinal statement than a name tag.

A depiction of Christ will be accompanied with two pairs of Greek letters, ‘IC XC', placed either side of his halo – an abbreviation for ‘Jesus Christ Saviour’. Similarly, the halo of the ‘Mother of God’ will be bracketed with ‘ΜΡ ӨΥ’, the title determined at the Council of Ephesus in AD 431, to affirm her divine status. It also translates as ‘Bearer of God’. Irrespective of their place and time of origin, icons of Christ and the Virgin will always bear these Greek labels – a continuation of 1,500 years of tradition.

The halo of Christ has a distinctive cruciform motif: the three visible parts may contain three Greek letters, an abbreviation of ‘The One’, The Being’, ‘He Who Is’ from Revelation (1:8), and the title of God from the Book of Exodus (3:14).

The order of these letters can be useful for distinguishing between similar Russian and Greek icons of ‘Christ Pantocrator’ (Pantocrator meaning ‘almighty’ or ‘all-powerful’). The Saviour’s Russian halo reads clockwise as: ‘Ѡοн’ (omega, omicron, nu), whereas Greek haloes read differently: ‘οѠн’ (omicron, omega, nu), if the letters are shown at all.

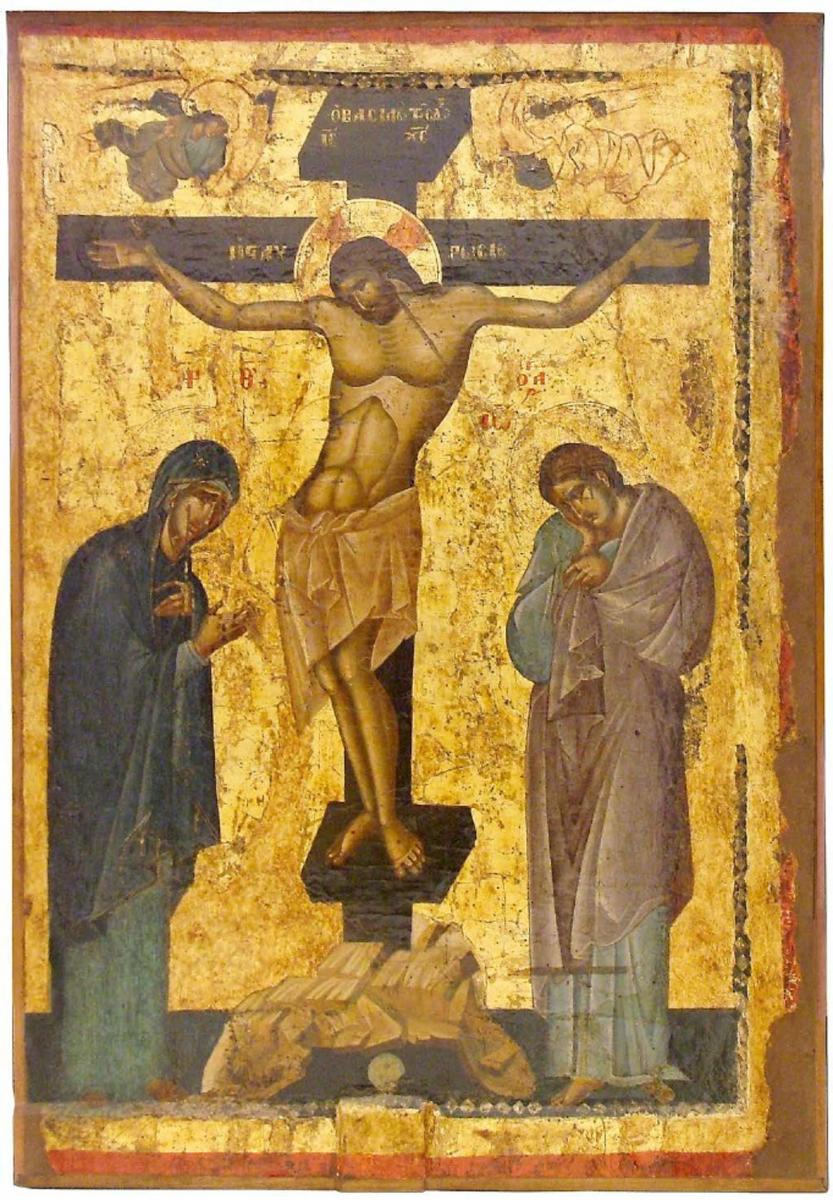

Detail, Saint Luke, painted by Master Apsalon Vujicic, 1672–73, Monastery of Moraca

Detail, Saint Luke, painted by Master Apsalon Vujicic, 1672–73, Monastery of Moraca

4. ICONS AND 'WRITING'

A Byzantine dispute worthy of Monty Python exists as to whether icons are ‘written’ or ‘painted’.

Certain groups of English speakers have introduced the phrase ‘icon writing’, which is often innocently echoed by those newly beguiled by the subject who, sensing a distinction between icons and secular art, assume it requires idiosyncratic language.

The phrase is not generally used by professional, long-established iconographers and scholars in the field. They talk instead about ‘icon painting’.

While both groups regard the icon as analogous to written scripture, the problem stems from an over-literal translation of Russian and Greek verbs. Both of these languages use one verb for ‘write’ and ‘paint’, while in English we have two verbs. In old Greek, graphein could mean either, depending on context. In modern Greek, graphos translates as ‘to write’, while zōgraphisō, used idiomatically, means ‘to create with paint’. It is the same in old and modern Russian with pisat and zjivopis. Presumably, St Luke as both evangelist and proto-iconographer did both.

While it is obvious that most icons are painted, they are also carved, cast, embroidered, engraved, printed and even baked. The monks of Mount Athos, Greece create wheat cake ‘icons’ by pressing an icon pattern into the cake and filling in the design with coloured sugars.

![]() Our Lady of Lewisham, painted in 2015 by our expert, Helen McIIdowie-Jenkins

Our Lady of Lewisham, painted in 2015 by our expert, Helen McIIdowie-Jenkins

5. ICON PAINTING – A MALE PRESERVE?

Historically, icon painting was the domain of male practitioners. They were either ordained or devout laymen sanctioned by a priest or, from the 19th century, production-line workers in commercial workshops.

Today, the majority of those painting icons are female, with many women teaching and researching in the field. In the UK, icon painting courses will have 75% to 90% female participation or more.

Although icon painting integrates many art practices once considered ‘feminine’ – namely respectable, small-scale subject matter, drawing, linear detail, pattern and painstaking ‘craft’ processes – the current popularity of icon painting among women may be due to the fact that it offers a new and meaningful form of female devotional practice, wellbeing and spirituality.

Irrespective of gender, the classic egg tempera (not ‘tempura’) method is a demanding, nuanced and deceptively difficult painting technique. Ten to 15 or more pigments might be used in an average icon, all of which behave differently (in a gritty, opaque, transparent, ‘floaty’ or greasy manner) when mixed with the egg yolk and water binder.

Icons are symbolically painted ‘dark to light’ using a variety of techniques. These include petit lac, glazing, scumbling, dry-brushing, cross-hatching, delineation, miniaturist detail and signwriting. Mixtures of three to five pigments are common, particularly for the requisite dark flesh underpainting (usually a dirty olive shade). The ‘non-personal’ parts are painted first (robes and background elements), followed by the ‘personal parts’ (the face, hair and hands).

The exquisite end results are a continuation of this, one of the most enduring art forms in the history of art.

HELEN'S TOP TIPS

See

An ideal place to see icons in their proper context is at your local Orthodox church, although many icons may be reproductions. Here are a few sites:

- Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Dormition, Ennismore Gardens, London

- The Serbian Orthodox Church of the Holy Prince Lazar, Birmingham

- The Holy Patriarchal and Stavropegic Monastery of St John the Baptist (Greek Orthodox) Tolleshunt Knights, Essex

- The Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St Luke, Glasgow

- The Orthodox Church of Archangel Michael and Holy Piran (Pan Orthodox) Ponsanooth, Cornwall

- Russian Orthodox Parish of the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God and the Greek Orthodox Church of St Nicholas, Cardiff

Icon collections

- The British Museum, the V&A and the Temple Gallery in London

- Some London auction houses hold summer and winter sales of Russian paintings and works of art, which include icons. Public viewing is possible for a few days prior to the auction with informative online catalogues published about a month before

- Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery has an interesting collection of icons from a bequest

- St Seraphim’s Trust, Little Walsingham, Norfolk – a pilgrim chapel and icon museum is housed in the former railway station and features icons in the Russian tradition by the lay brothers from 1966 to 2010, who were among the first contemporary iconographers in the UK

Good reads

Online

- Icons and their Interpretation is an ever-growing anthology of fascinating articles on all aspects of icons and iconography

- A medieval sourcebook: In Defence of Icons, c.730, for those interested in the theological distinction between veneration and worship from St John of Damascus writing in the 8th century

In print

- Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Guide to Imagery by Alfredo Tradigo, Getty, 2006

- Festival Icons for the Christian Year by John Baggley, Mowbray, 2000

- Icons by Robin Cormack, British Museum Press, 2007: the museum’s notable collection of icons is not always on display, but Professor Cormack, a leading art historian of Byzantine art, introduces the history of icons, their function, meaning and making with reference to examples from the collection

- Icons: Divine Beauty by Richard Temple, Saqi, 2004

- The Icon: Truth and Fables by Irina Gorbunova-Lomax, China Orthodox Press Publishing Company, 2018

About the Author

Helen McIldowie-Jenkins

Helen is a graduate of the Courtauld Institute of Art, specialising in trecento panel-painting, Russian and Byzantine icons and iconography. Helen has worked at London’s Russian Art Auction House (MacDougall Arts) and in museums and adult education. She is currently working on a major icon commission for a London church and writing a book on icon painting. Among her lectures for The Arts Society are From Cradle to Cave: The Iconography of the Nativity in Late Medieval Italian Art, Strange Virgins and Quirky Saints: Intriguing and Unusual Icons, Finding Francis: A Visual Pilgrimage through the Art of Assisi and Madonnas and Miracles: The Golden Age of Sienese Painting, 1250-1350.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition