This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on Rupert Bear

Become an instant expert on Rupert Bear

12 Nov 2020

It's 100 years since Rupert, one of the best-loved children's stories, first appeared in the Daily Express. We asked our expert, Howard Smith, for the bear facts

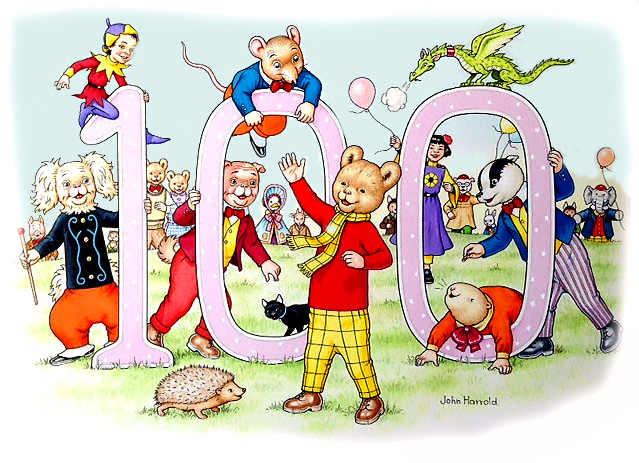

Illustration by John Harrold, the third official Rupert Bear artist

‘I am always so glad to know that my little readers like Rupert and his adventures. With much love and kisses and thank you again for your nice letter…’

From a letter by Rupert’s original illustrator, Mary Toutel, to a young fan, 1926

Mary Caldwell

Mary Caldwell

1. IT TOOK TWO TO CREATE RUPERT BEAR

Mary (née Caldwell) Tourtel (1874–1948) is credited with creating Rupert, but my recent research has found that this is not entirely the case. It appears it was her husband, Herbert Tourtel (1874–1931), who created Rupert, and Mary made the illustrations.

Mary was born in 1874; her father was a stained-glass artist at Canterbury Cathedral. She was a shy child, artistic and with a gift for drawing. Her oldest brother, Edmund, became one of the finest animal artists in South Africa, illustrating a well-known work at the time, James Percy FitzPatrick’s Jock of the Bushveld. He trained at Thomas Sidney Cooper’s School of Art in Canterbury. Cooper (RA) was a celebrated sheep and cattle painter.

Mary followed Edmund to Cooper’s school and developed into another exceptional animal illustrator. Cooper insisted all his students went to the local abattoir to study muscle structure which explains why Mary became a vegetarian.

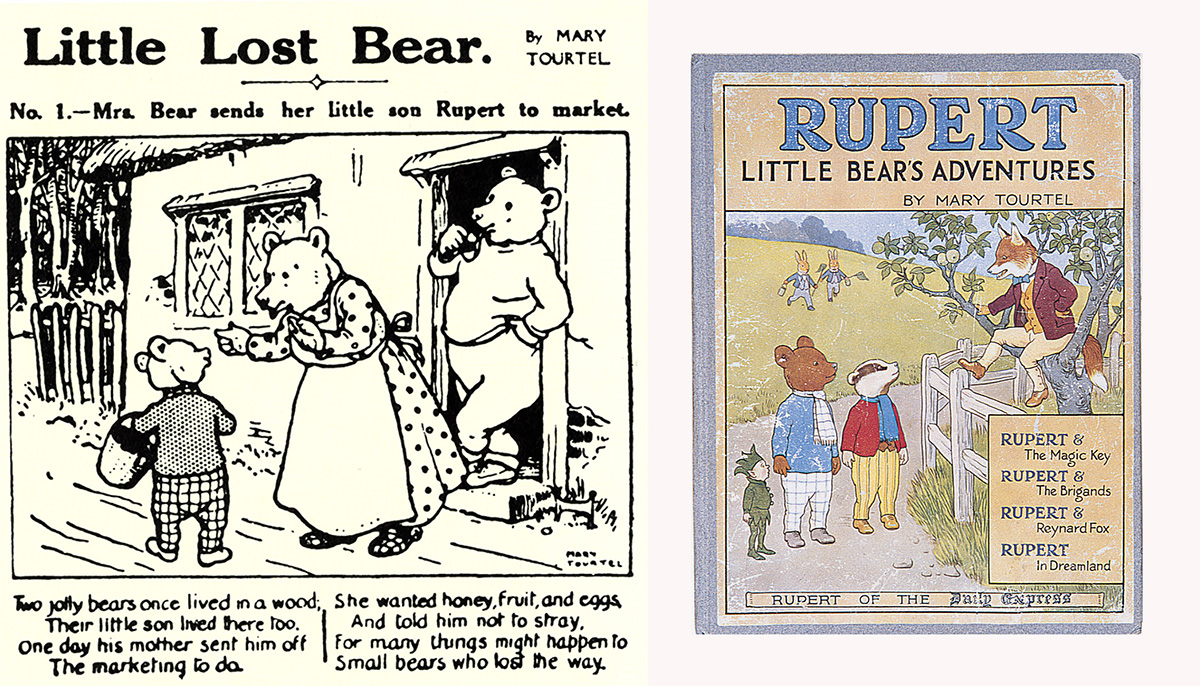

The first Daily Express 'frame' and the "Rupert Little Bears Adventures" – in which Mary coloured Rupert in a blue jersey. Later, Rupert swapped clothes with Bill Badger adopting the distinctive red jersey and yellow check trousers.

The first Daily Express 'frame' and the "Rupert Little Bears Adventures" – in which Mary coloured Rupert in a blue jersey. Later, Rupert swapped clothes with Bill Badger adopting the distinctive red jersey and yellow check trousers.

2. THE TALE OF HERBERT TOURTEL

Herbert Bird Tourtel was born in the same year as Mary, in St Peter Port, Guernsey, the son of a struggling tailor. He gained a scholarship to the Elizabeth College and then went to work in his father’s shop, which he found dull. Instead, obsessed with the Romantic poets, he spent his time writing poetry. He persuaded a local printer to publish his epic poem The Coming of Ragnarök, which led to him gaining recognition as a minor British poet.

Herbert was also fascinated with mythology, the cautionary tales of the Brothers Grimm and, especially, the folklore of Guernsey. His uncle, the Reverend Robert Henry Tourtel, who had helped him to get his scholarship to Elizabeth College, also arranged a scholarship for him to go to Trinity College, Cambridge, to read Divinity. He lasted the course but did not take the exams (he didn't want to become a vicar). Instead he tried to get his portfolio of poems published in London and was told he should get them illustrated. Without any money to do so, he went to the Royal College of Art, where he asked for a student to illustrate them as a ‘free of charge’ project. That’s where he met Mary, who had won a place there from Canterbury.

Herbert went on to get a job as a reporter with the new Daily Express in 1900. With a good salary under his belt he proposed and promptly married Mary, who freelanced for the next 10 years, while Herbert was promoted to night editor and acting editor during the Great War.

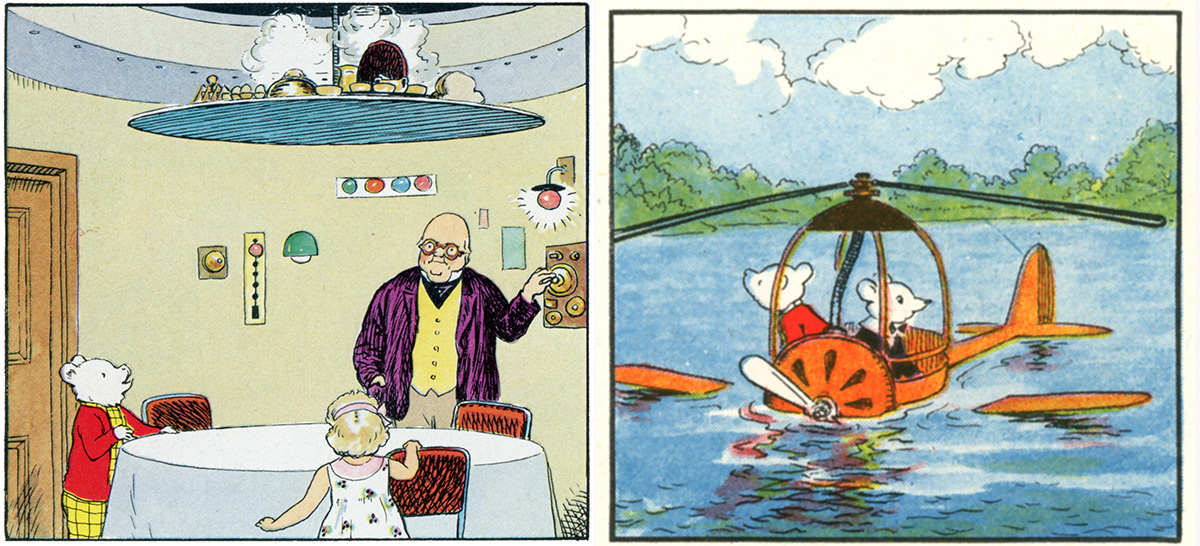

Ahead of his time: Bestall featured scientific inventions before they had actually first appeared

Ahead of his time: Bestall featured scientific inventions before they had actually first appeared

3. A BACKDROP OF BEARS AND CIRCULATION WARS

In 1920 Lord Beaverbrook was concerned by the success of rival paper the Daily Mail. It had three times the circulation of his Daily Express. He instructed Herbert to find out why and come up with a solution.

One of the Daily Mail successes was its popular anthropomorphic mouse story, Teddy Tail, which had run since 1915. By 1919 the Daily Mirror had Pip, Squeak and Wilfred. Musing on this, Herbert looked to the current popularity of bears. Dancing bears from Eastern Europe featured in some 169 travelling fairs active at the time. In Germany Margarete Steiff, a seamstress, had begun to make her famous bears; and in the US, Theodore Roosevelt dropped the moose as his campaign mascot for a bear – the so-called Teddy Bear.

As a result, Herbert recommended a bear story for the Daily Express to Beaverbrook and offered his wife's services to illustrate it (he hadn't asked her). So it was that Mary, at the age of 46, drew her first frame on the 8th November 1920. Herbert wrote and conceived the stories naming the little bear Rupert, after the poet Rupert Brooke.

Herbert’s input on the project was kept secret – he wanted Mary to get the fee. This is why Rupert is always credited as ‘by Mary Tourtel’. Herbert died in 1931 from tuberculosis, so Mary continued both writing and illustrating the strip. Rupert was by then established with generations of children and adults alike – a creation entirely the result of a circulation war.

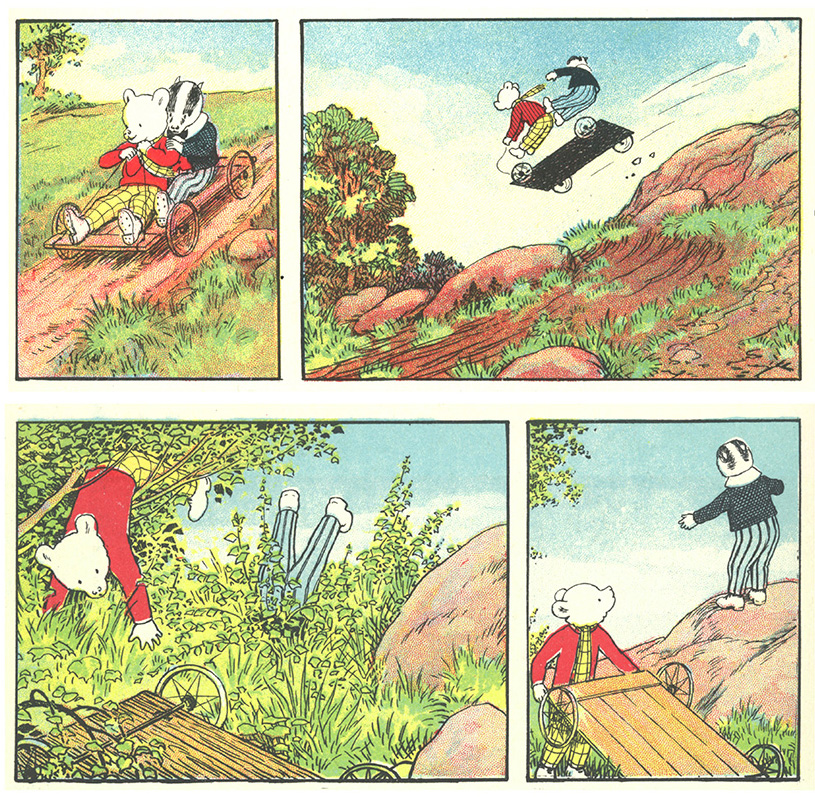

It’s a cliffhanger: Rupert and Bill Badger sail over a ridge (top frame) and readers wouldn’t discover if they’d landed safely until the next day (bottom frame)

It’s a cliffhanger: Rupert and Bill Badger sail over a ridge (top frame) and readers wouldn’t discover if they’d landed safely until the next day (bottom frame)

4. ENTER ALFRED BESTALL

Alfred Edmeades Bestall (1892–1986) took over as the second official Rupert artist – and writer – in 1935, when Mary resigned through ill health. He was trained at the Central School of Art in London as an illustrator and a painter in oil, watercolour, line and wash.

He made significant changes to the strip, with three-dimensional illustrations and more facial expression, and set the stories in a 1930s time warp. He also wrote the stories for adults, with adult themes (see Rupert and the Mare’s Nest and Rupert and the Gooseberry Fool). He brought in humour, so parents enjoyed both reading the stories and seeing their child’s reaction to the storylines.

In time more ‘friends’ for Rupert were created to extend the storylines. Each day Bestall created, with two, or sometimes three, frames, a continuation of the previous day’s story, with the last frame being a cliffhanger for the next day. He introduced scientific inventions years before they became reality, such as fixed-wing helicopters. He also continued with Herbert’s passion for Rupert to be flying off to adventures.

Such was the popularity of the stories that, from 1935, they started to be reprinted and professionally coloured in the annuals that many of us are familiar with today.

5. THE SECRETS OF RUPERT'S SUCCESS

The initial Rupert stories were full of death, witchcraft, elves, ogres and goblins – all of which children loved. Then there was Herbert’s satisfying ‘formula’ for the structure of each story: Rupert leaves home, has an adventure and returns safely home – not forgetting those cliffhangers woven in to the close of certain frames, to keep readers coming back for the next day’s instalment. This became the form for most children’s stories. In the 1920s, William, of the famous Just William stories by Richmal Crompton, left home, had an outrageous adventure with the Outlaws and returned home. By the 1940s, Enid Blyton’s Famous Five left home, went on a Kirrin Island adventure and, yes, you guessed it, came home.

Then there is the hugely successful element of anthropomorphism. Great stories like The Wind in The Willows (1908) and Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), and characters like Mickey Mouse (1928) and Paddington (1958), were all anthropomorphic, and people were drawn to this. It’s considered possible that all these had their genesis in the hugely popular Louis Wain drawings of large-eyed cats in the late Victorian era.

All the Rupert stories were creative, with elements of fantasy, mythology and science. They became part of Christmas, with the 1950 Rupert Annual selling 1.6 million copies (with possibly 1.6 million oranges to go with them in the festive pillowcase).

HOWARD'S TOP TIPS

The work of children’s book illustrators often features less prominently than that of one-off artists. Yet a trove of their work can be found easily – and for very little expense – in books in charity shops. Rupert annuals are worth discovering to marvel at the ingenuity, visual puns and graphics in telling stories over 50 frames (or ‘days’ in a newspaper).

Mary Tourtel also created superbly illustrated animal books. I recommend looking at her A Horse Book, published by Grant Richards in 1901, for its remarkable illustrations of working horses.

Alfred Bestall illustrated AA Milne and Enid Blyton books, as well as contributing to Punch for many years. There are several biographies covering his large range of work.

If you’d like to know more about Rupert, there is a society called The Followers of Rupert.

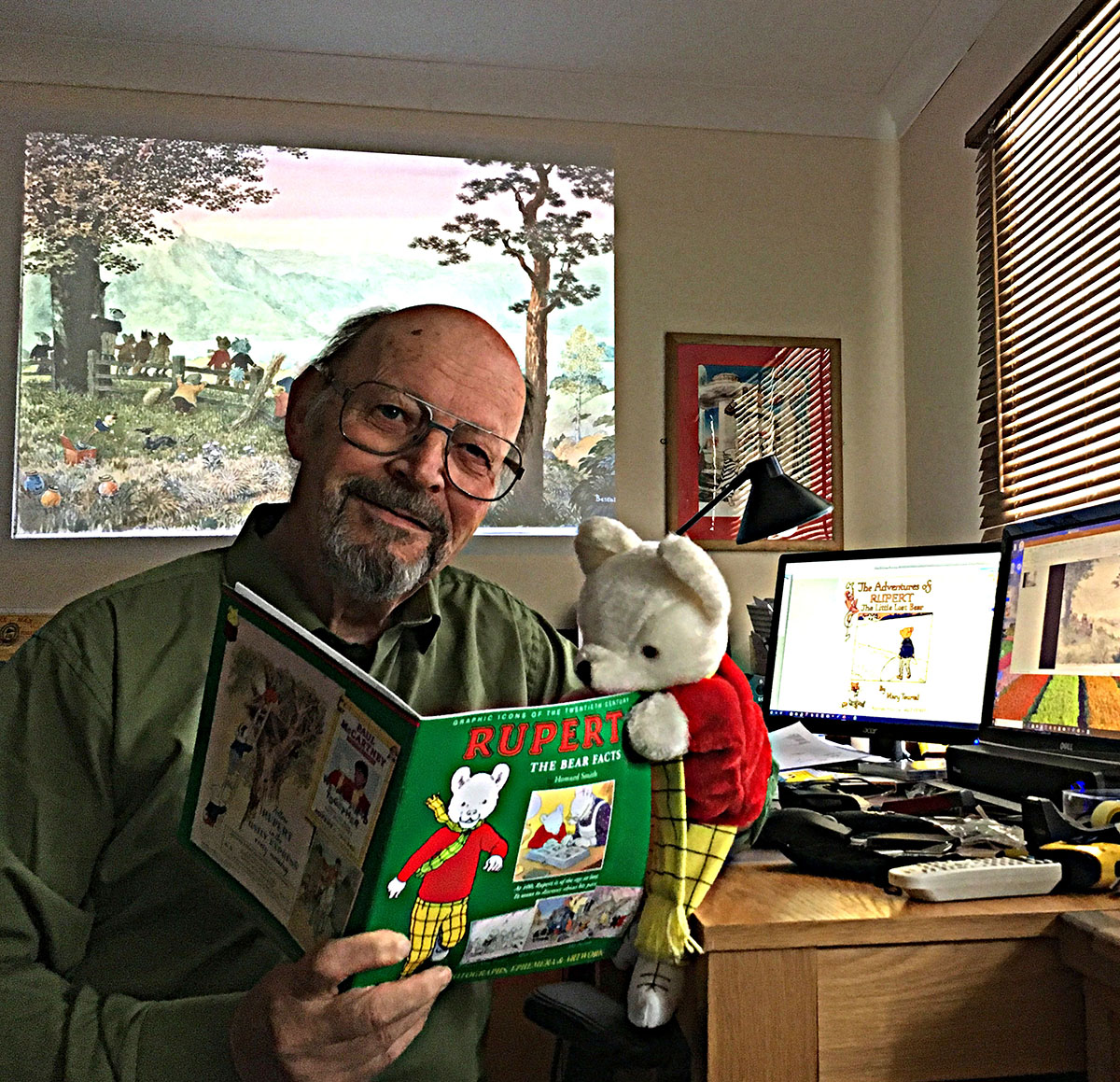

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

With an MA from Trinity College, Dublin, Howard’s early career in graphic design was spent at national and international advertising agencies, before he set up his own design studio and printworks 40 years ago. He has featured on radio and television, has published art and social history books, and has curated exhibitions. Among his lectures for The Arts Society in his series of 'Graphic Icons of the Twentieth Century' are: The GPO Film Unit, Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler’s Filmmaker and Rupert, the anthropomorphic bear. Find out more from his showreel link.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT FEATURE...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

Show me another Instant Expert story

About the Author

Howard Smith

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition