This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Prints that once fuelled Fake News

Become an Instant Expert on the Prints that once fuelled Fake News

26 Oct 2021

There’s nothing new about sham news – or outrageous hoaxes. In the 18th century, satirical prints helped spread such stories, duping thousands. Our expert, Ian Keable, looks at some colourful examples

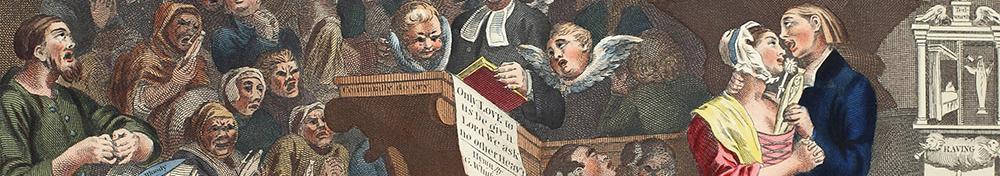

Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism, a print originally by William Hogarth, here re-engraved and hand-coloured by Thomas Cook

Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism, a print originally by William Hogarth, here re-engraved and hand-coloured by Thomas Cook

‘...a mixture of humorous and sublime satire…which would alone immortalise his unequalled talents’

- Horace Walpole, art historian, man of letters and politician, on William Hogarth’s Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism

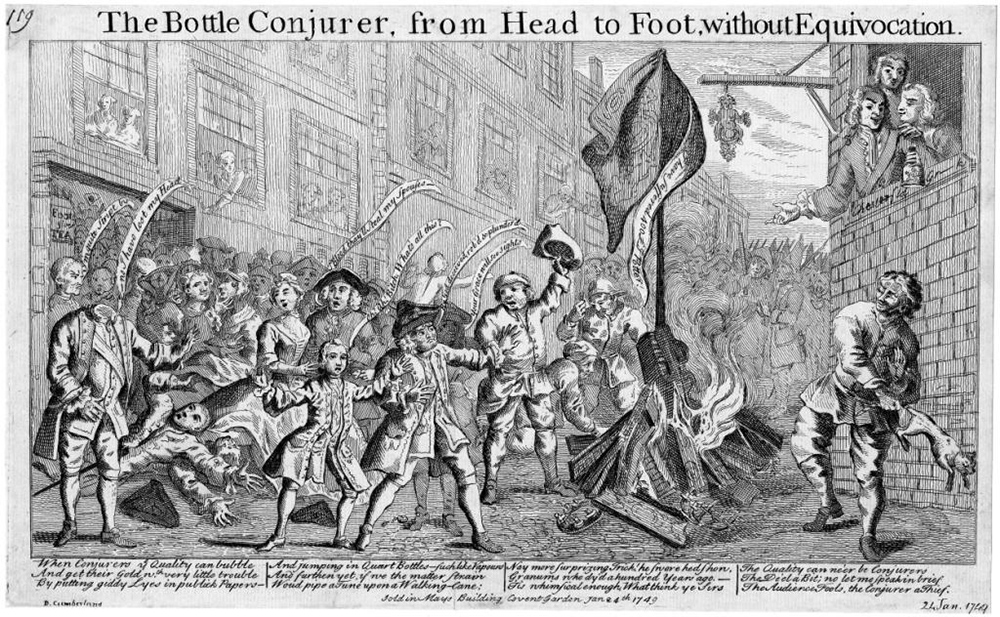

Very Slippy Weather by James Gillray

1. THE RISE OF HOAXES AND POLITICAL ART

Hoaxes and satirical prints had been in existence long before the 18th century, but both came of age in this period.

Prior to 1700, information about individual hoaxes is scant. What we know about them is dependent on perhaps a single newspaper article or pamphlet.

This all changes with the exponential growth in the distribution and readership of newspapers in the Georgian era. Alongside these came the monthly journals – The Gentleman’s Magazine being the most famous – but knowledge of hoaxes was not confined to these sources. In addition, there were pamphlets (a mix of the polemical and humorous), theatrical recreations on stage and even Old Bailey court transcripts.

And, of course, there were satirical prints.

Above we see James Gillray’s Very Slippy Weather (1808). Famous for his etched political and social satires, here Gillray shows a man who has slipped outside Humphrey’s printing establishment at 27 St James’s Street in London. Somehow he manages to keep the thermometer he is holding upright, while those peering at the caricatures in the window remain oblivious to his plight.

A skilled art form, satirical prints such as this emerged in the 18th century due to a split in power between the monarchy and cabinet government. Before then, with a sole dictator (the reigning monarch), the production of anything satirical connected to the existing regime was likely to lead to imprisonment, or worse.

The man who received the brunt of early satirical imagery was the first prime minister, Robert Walpole, who came to power in 1721. As the most prominent UK politician for over 20 years, he was inevitably the target for those dissatisfied with his party’s policies. By coincidence, in the same decade, the man who would become known as the greatest satirical artist of all, William Hogarth, appeared on the scene.

Cunicularii or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation, 1726, by William Hogarth

2. CATCHING HOGARTH'S EYE

The most famous hoax of the 18th century was that of Mary Toft of Godalming, who claimed, in 1726, that she was giving birth to rabbits.

The young Hogarth could not resist.

In response, he produced Cunicularii or The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation, which shows Mary surrounded by male attendants and her sister-in-law, while giving birth to rabbits, which are seen scattered on the floor. Some are merrily scampering around – whereas others, which is what happened in reality, had (apparently) emerged from Mary in pieces.

The title The Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation is a wry reference to the predominantly male midwives who were taken in by Mary and her ruse. (As an aside, Mary’s stated reason for this hoax was to make money, but it was exposed before she achieved this aim.)

Towards the end of his life, in 1762, Hogarth reprised the image of Mary and her rabbits in one of his most brilliant engravings, Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism (see the first image, at the top). This purported to show that those who practised religious ‘enthusiasm’, in particular the Methodists, shared similar characteristics to those who were taken in by hoaxes. Within the print he included reference to some of these.

Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism was produced in the same year that ‘The Cock Lane Ghost’ made her appearance. This famous hoax involved a ‘spirit’ who claimed, communicating by rapping or knocking, that she had been poisoned by her lover.

In Hogarth’s print of this story he depicts the ghost with a mallet in her hand.

He shows the wild-eyed congregation clutching this effigy of the ghost grasping a mallet, rather than the usual effigy of the Virgin Mary. Mary Toft, along with the 17th-century ‘Drummer of Tedworth’ (an apparent poltergeist, said to have caused havoc in a home), are incorporated into the image too, as other examples of widespread hoaxes.

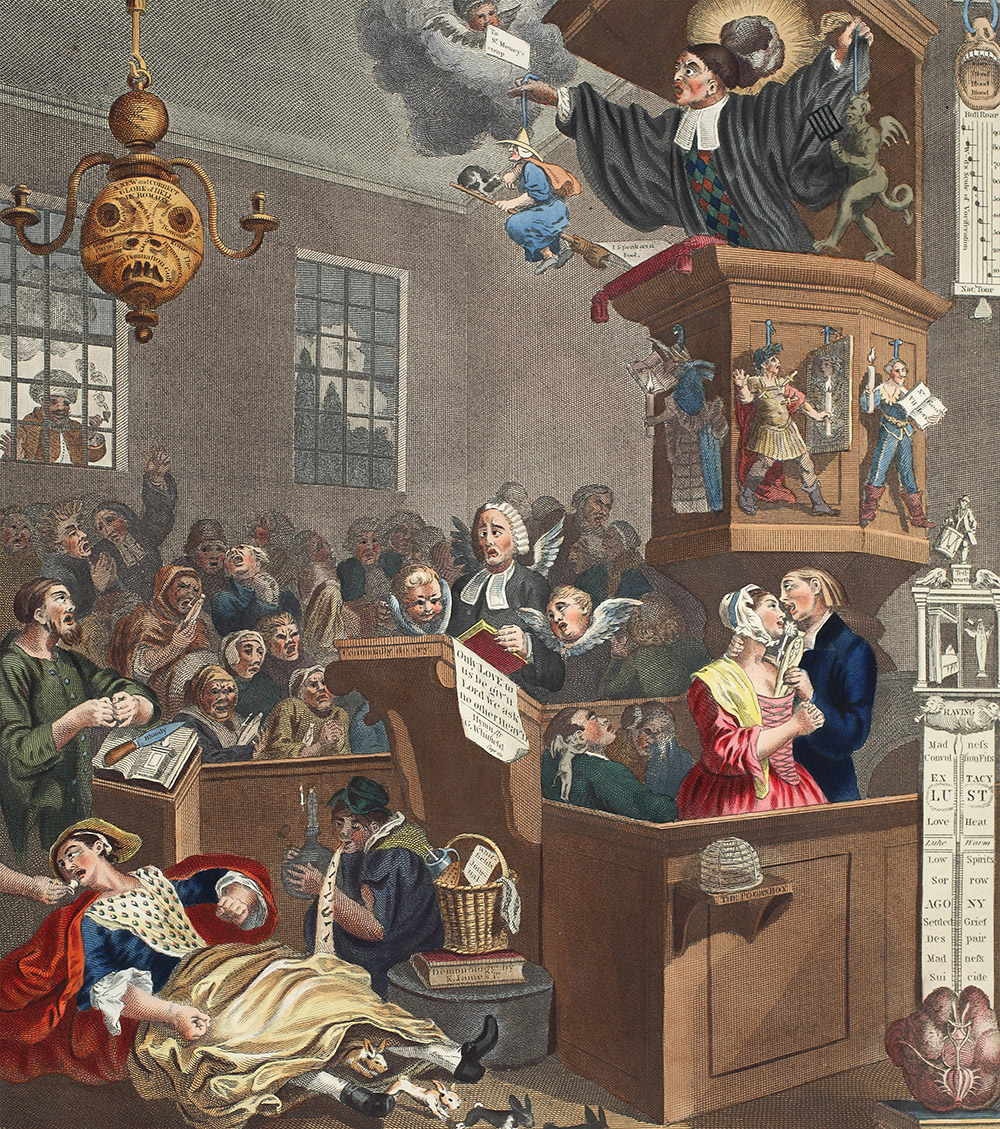

A print that appeared eight days after ‘The Bottle Conjurer’ hoax

A print that appeared eight days after ‘The Bottle Conjurer’ hoax

3. LINKS TO THE PRESS

Today we think of Hogarth’s work, and that of his successors, including Gillray and George Cruikshank, as powerful art. But at the time these artists were considered to be jobbing journalists. They would read the papers, listen to gossip in coffee houses and take what they heard and read to incorporate topical and humorous detail into their work.

Take the story of ‘The Bottle Conjurer’ hoax of 1749.

First came the advertisement: that a man would climb inside a bottle on the stage of the New Theatre in the Haymarket.

The crowds turned up in their hundreds to see this miracle, but unfortunately the performer did not.

A riot broke out as the audience realised they had been duped. The inside of the theatre was destroyed and much of the interior, including the seating, stage and scenery, was taken outside and burnt on a huge bonfire.

A satirical print was produced by an unknown artist, which showed not just the melee outside the theatre but details that had clearly been gleaned from newspaper reports. For instance, that the curtain of the theatre was hoisted as a flag on a pole at the centre of the flames; and that troops from a nearby garrison arrived too late to dispel the mob, so all they could do was warm their hands on the fire.

Another detail in the image alluded to the contemporary story of the Duke of Cumberland – infamous today for his part in the massacre of the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden some three years earlier – whose sword had been stolen. He had advertised in the papers for its return, offering a reward of 30 guineas. Featured here, on the left, is a headless man with an empty scabbard – a double reference to the duke’s loss of both temper and weapon.

The gypsy Mary Squires, who satirical artists chose to show as a witch

The gypsy Mary Squires, who satirical artists chose to show as a witch

4. SPINNING PROPAGANDA

It will come as no surprise to learn that hoaxes of this period were skewered by some to emphasise prejudicial views. In turn, satirical prints based on the hoaxes fed those prejudices.

Take, for example, the strange story of the maidservant Elizabeth Canning. In 1753 she went missing. When she reappeared, some four weeks later, she claimed she had been kidnapped by two men, then locked in the loft of a house by a gypsy called Mary Squires.

This story coincided with a prevalent antagonism towards gypsies, which was linked with anti-Semitism. Mary Squires, it seems, was considered unattractive; she had a hunchback and a prodigious lower lip. It was easy for the cartoonist to depict her as a witch and thereby link her to nefarious and underhand activities. As a result, for many she became a symbol of hate, reinforcing a dislike of gypsies.

Throughout the 18th century in Britain there was also a xenophobic attitude towards the French, not entirely surprising given the number of wars fought between the two countries.

Any opportunity to depict the French as duplicitous, cunning and untrustworthy was seized upon.

In 1784 Chevalier de Moret, a pioneering aeronaut, spectacularly failed to fly in a hot-air balloon. Many spectators had paid to witness his flight. In response, one print shows a sinister French man pointing towards the skies, to where a wide-eyed gentleman is staring. With his other hand, the Gallic figure is picking the man’s pockets. Yet another example, the image is suggesting, of the evil French hoaxing the gullible English.

In retrospect the depiction is rather ironic, given that de Moret was Swiss by birth.

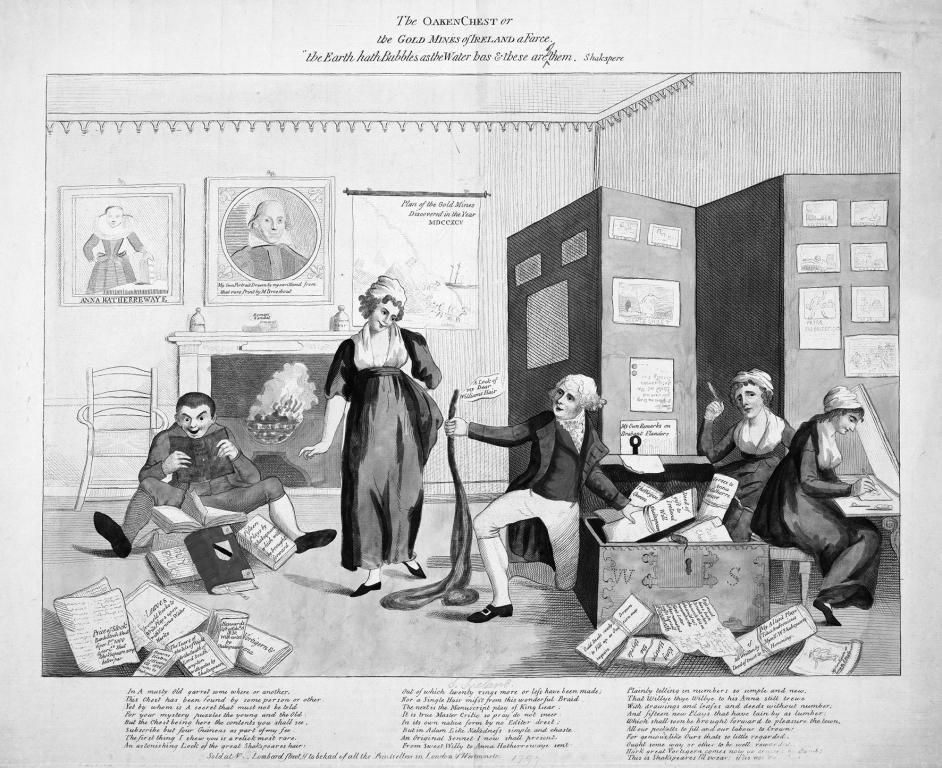

The Ireland family, as shown by artist John Nixon

5. INTERPRETING THE PAST

The value of satirical prints in helping us understand society of the time should not be underestimated. We can learn as much about the 18th-century populace’s attitude towards Napoleon, for example, by looking at how he was shown in cartoons, as we can by reading history books. When it comes to hoaxes, we can see through the eyes of the satirist how their contemporaries were interpreting the story.

An example comes with one of the most famous literary hoaxes of the 18th century.

This was perpetuated by William-Henry Ireland, who forged Shakespearean papers and writings, culminating in the supposed discovery of a previously unknown new play by the Bard, called Vortigern, based on the 5th-century king of the Britons.

The play was even staged for one night at the Drury Lane Theatre in April 1796.

William-Henry handed over all his forgeries to his father, Samuel, who was a Shakespearean obsessive. Two questions that arise are whether Samuel was aware of the fraud, and whether William-Henry acted alone. My own belief is that Samuel was genuinely taken in by his son (who eventually confessed to the hoax); and it is now known that William-Henry did indeed produce everything himself.

Satirical prints of the time, however, reveal this was not the prevailing view.

Gillray engraved a print of Samuel Ireland called Notorious Characters. No. 1, inferring that Samuel was party to the whole affair.

Samuel seriously contemplated suing Gillray for libel.

Another print, The Oaken Chest (above, or The gold mines of Ireland, a farce) shows the Ireland family (including Samuel’s wife and daughters) churning out the Shakespearean ephemera. William-Henry himself is shown as a dim-witted youth, quite incapable of producing anything approaching the quality of the Bard’s writings.

This was an image typical of its genre: a satirical print, imaginatively produced in response to a prominent hoax, providing a piece of cultural commentary, complete with the lampooning of stereotypical characters. It shows us that satirical prints, the digital memes of their day, can shed more light than many a written word on wild, 18th-century hoaxes.

IAN'S TOP TIPS

See

The best place to see satirical prints is in the comfort of your home, where they can be viewed in high resolution, enabling you to zoom in on the specific details. The two best sources, where the image can be downloaded to your device, are the Department of Prints and Drawings in The British Museum and the British Cartoon Prints in the Library of Congress.

Good reads

There are many books on 18th-century satirical prints, but I especially recommend the lavishly illustrated City of Laughter: Sex and Satire in Eighteenth-Century London by Vic Gatrell, 2006.

For more on the hoaxes mentioned here, see:

The Imposteress Rabbit Breeder by Karen Harvey, 2020

The Cock Lane Ghost: Murder, Sex and Haunting in Dr Johnson’s London by Paul Chambers, 2006

The Canning Enigma by John Treherne, 1989

The Boy Who Would be Shakespeare: A Tale of Forgery and Folly by Doug Stewart, 2010

My own book, The Century of Deception: The Birth of the Hoax in Eighteenth-Century England, 2021 (published by Westbourne Press) covers 10 hoaxes. It includes the four above, together with the Bottle Conjurer and Chevalier de Moret. The remaining four, two of which were carried out by Jonathan Swift and Benjamin Franklin, are not depicted in any existing satirical prints. For more on the book, see here.

About the Author

Ian Keable

Ian Keable studied philosophy, politics and economics at the University of Oxford, qualified as a chartered accountant and then became a professional magician. He is a member of The Magic Circle with gold star, has won awards for comedy magic and performed on television. He has also written and presented radio programmes for the BBC. He divides his time between performing magic, giving talks and researching and writing. One of his previous books is Charles Dickens Magician: Conjuring in Life, Letters and Literature (2014). Among his Arts Society talks, apart from one with the same title as his book, are The Art of Trickery: how magicians are seen in paintings, prints and cartoons, James Gillray: first political cartoonist and The History of Cartoons: from William Hogarth to Private Eye.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition