This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on our historic canals

Become an Instant Expert on our historic canals

27 May 2021

Britain’s historic canal network is a giant web, extending more than 2,000 miles across England, Wales and Scotland. Most of our canals are now more than 220 years old, and each one exhibits the ingenuity and flair of the pioneering engineers who created them. They were a revolutionary transport network that created trade and helped fire the Industrial Revolution. Today only the National Trust and the Church of England have more listed buildings and structures than our inland waterways. Arts Society Lecturer Roger Butler takes us on a tour

Traditionally decorated narrowboats featuring the bright folk art of the canals

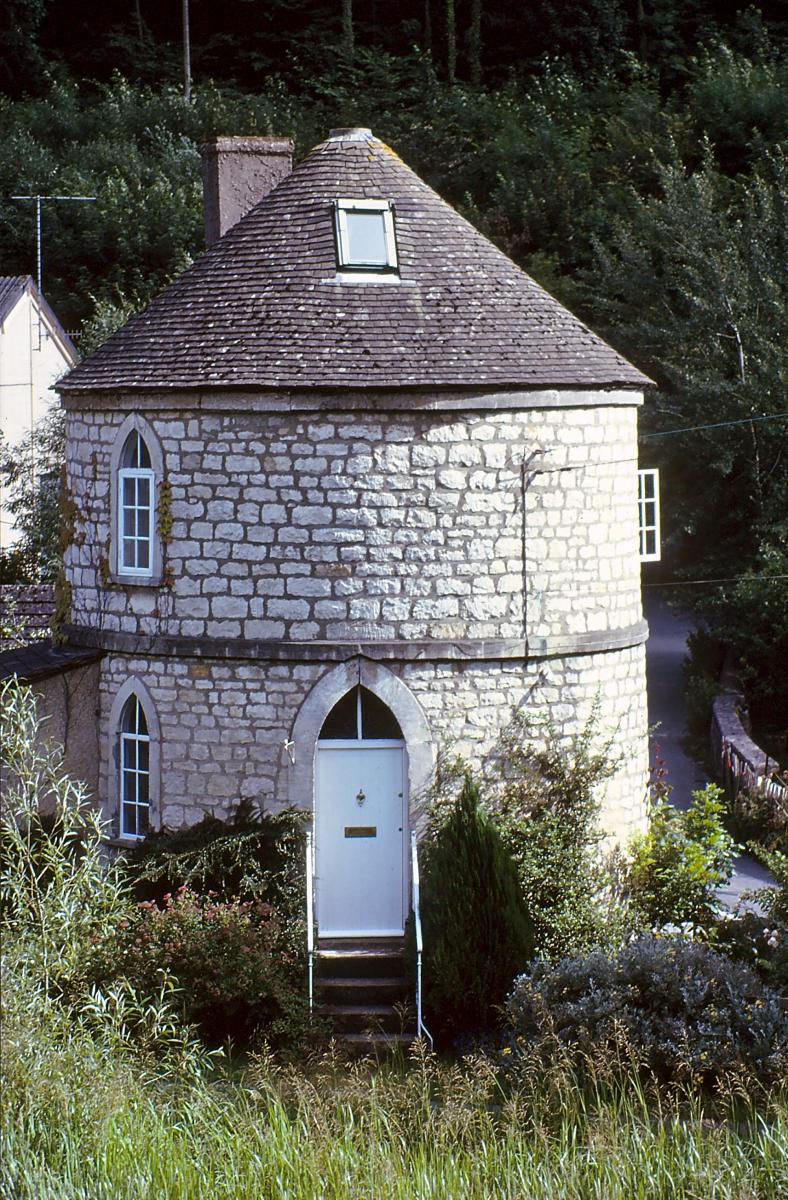

An unusual canal cottage by the old Thames & Severn Canal at Chalford in Gloucestershire

An unusual canal cottage by the old Thames & Severn Canal at Chalford in Gloucestershire

1. VIEWS AND PAGODAS

A huge variety of buildings once served our network of canals, and many of these are still striking landmarks. Examples include warehouses, cottages, offices, toll houses, stables and maintenance yards. Most were designed with form and function in mind, and many canals retain their own distinctive vernacular.

The buildings were designed to impress. Our canal system was the motorway network of its time, and the gaunt warehouses that rise sheer from the water were once the equivalent of bustling motorway service stations. On the Leeds and Liverpool Canal their timber canopies sail over the water like Chinese pagodas. In Bath, the Georgian offices of the Kennet and Avon Canal were built on top of a tunnel; and a manager’s house near Birmingham had sweeping bays that gave unfettered views across an important junction.

The quaint barrel-roofed cottages on the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal are found nowhere else. Simple bridge-keepers’ houses on the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal were decorated with classical porticos, while fairytale circular cottages by the Thames and Severn Canal are thought to be derived from the wool-drying kilns that once peppered the nearby hillsides.

Humble buildings are interesting too. The former canal yard at Hartshill, near Nuneaton, includes stables, a dry dock, a blacksmith’s shop and an elaborate clock tower – all set behind a high monastic wall that protectively curves towards the adjacent humpbacked bridge.

This eye-catching bridge spans the start of the Grand Union Canal at Little Venice in London

This eye-catching bridge spans the start of the Grand Union Canal at Little Venice in London

2. HEROIC ENGINEERING

The construction of the canals used cutting-edge engineering, but it was Leonardo da Vinci who originally sketched out the basic principles of the workings of our locks. While a consultant engineer in service to the Duke of Milan, he had been behind the construction of six canal locks, inventing a new, efficient gate system that required less manpower than the one before. This system was adopted worldwide.

The first canals hugged the contours of the land and meandered wildly through the countryside, but later engineers, such as Thomas Telford, used deep cuttings and tall embankments to forge more direct routes.

The achievements were extraordinary, with lock flights that rise like packs of dominoes, and aqueducts that soar with the grace of a trapeze artist. The locks at Bingley in West Yorkshire literally crash up the hillside, and the famous Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, near Llangollen, crosses the valley of the River Dee on 18 slender 126-foot masonry piers.

Sir Walter Scott called it the most impressive work of art he had ever seen.

Deep tunnels, where men ‘legged’ their boats through the dripping darkness, were sometimes more than two miles long. They burrowed under the Pennines, across the Cotswold watershed and beneath the Black Country. In some places inclined planes carried boats up and downhill and, in Cornwall, remarkable underground waterwheels powered the lifts on the Bude Canal.

Bridges take all shapes and sizes. There are small brick and stone arches, cast-iron spans with fine Gothic decoration, and chunky timber lift-bridges that could have been designed by Andy Goldsworthy. The snake-like turnover bridges on the Macclesfield Canal are almost works of art, but their clever spiralling horse ramps were simply a response to a towpath that moved from one side of the canal to another. Today, the interplay of light and shade is a photographer’s dream.

Cramped but colourful: a historic narrowboat

Cramped but colourful: a historic narrowboat

3. ON BOARD THE BOATS

Canals generated trade and the price of coal tumbled once boats were able to take it to market. Josiah Wedgwood invested in the Trent and Mersey Canal because he knew this would be the safest way to carry his pottery out of Stoke-on-Trent.

The first cargo-carrying narrowboats were made from oak and elm and were pulled by a horse led by a crew member. Their dimensions were limited by the size of the locks – a maximum length of 70 feet – and the depth of the water, and they were fitted with distinctive curved tillers.

The cramped cabins at the rear meant the bulk of each vessel could carry goods such as timber, slate, wheat and grain. Each dark cabin made the most of the limited space and included the essential stove and fold-out beds. Old sketches show attention was given to decoration with gleaming brasses and ornamental plates. They also show young children squeezed around their mother’s knee.

A wide range of boats developed to suit the needs of different waterways and some companies, such as Fellows, Morton & Clayton, operated famous fleets. Packet boat services carried passengers, luggage and parcels, and the equivalent of a commuter service once linked Paisley with Glasgow. Iron and steel boats appeared in the 19th century, and horses were then gradually replaced by steam power and, later, diesel engines.

Roses and Castles decorative canal ware – these cans were originally used to store

fresh water on the roof of the boats

4. DISTINCTIVE ARTS AND CRAFTS

The brightly coloured folk art of the canals, often known as Roses and Castles, is instantly recognisable, but its origins are lost in the mists of the 18th century. The first written reference to this unique work appeared in 1858, so it can therefore be regarded as a relatively new form of decoration.

Suggested origins have included links to Romany culture, ideas gained from the pottery industry and even artwork in distant Turkey and Bangladesh.

The roses seem rather English – although some are more like dahlias and chrysanthemums – but the romantic castles have a Bavarian twist, with tall turrets rising next to mountain lakes. Some think the extravagant red, yellow and green paintwork, which includes diamonds and six-petalled compass patterns, once helped the boaters offset the daily grind of muddy towpaths, hungry horses and limited personal effects.

Cabin doors, water cans and the sides of boats were embellished with gaudy paintwork, and even wash basins and stools would be carefully decorated. Ornate lettering was used to signify the boat’s name, owner or fleet, and this tradition, along with interpretations of Roses and Castles, continues today.

Other arts and crafts included decorative ropes and fenders, homely brown teapots, beautiful crochet and delicate lacework. Examples can be seen in canal museums, where displays of traditional artwork are also on display.

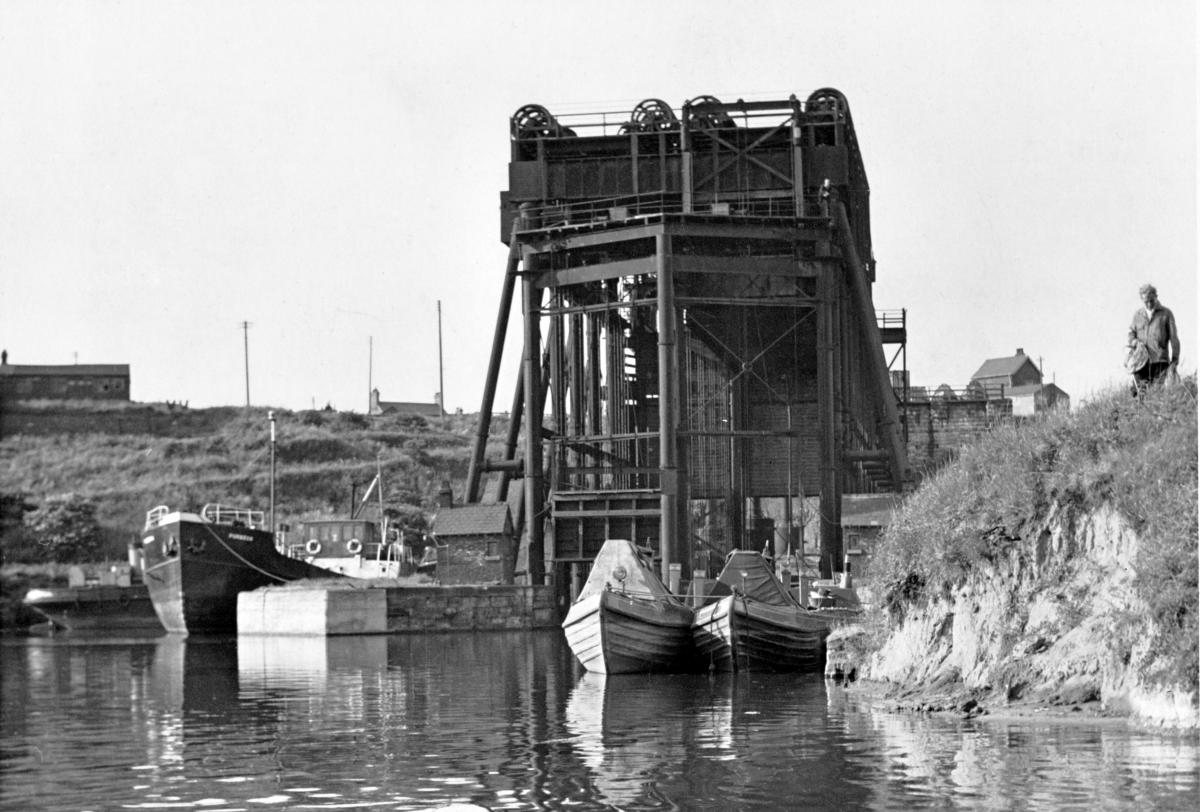

An archive image of the Anderton Boat Lift near Northwich in Cheshire

An archive image of the Anderton Boat Lift near Northwich in Cheshire

5. QUIRKY LANDMARKS

A range of unusual and unexpected structures developed alongside the canals. Some are now features of national importance, but others are almost lost among towpath hedgerows.

Pumping stations with tall chimneys pushed water from river to canal; lighthouses shaped as chess pieces guided boats towards the sea locks in Scotland; hefty carved signposts pointed a watery way to Birmingham; and tiny bothies were wet-weather hidey-holes for the men who maintained the waterways.

No two structures were the same and many were the result of local circumstances and inspired creativity.

The extraordinary Anderton Lift, near Northwich, was built to connect the Trent and Mersey Canal with the River Weaver and looks like a prehistoric spider. It was brought back to life in 2001. At Foxton in Leicestershire, a flight of 10 locks runs next to the remains of a steam-powered incline that once thumped and echoed over the surrounding countryside. And, in complete contrast, a series of World War II pillboxes are dotted alongside the Kennet and Avon Canal – these were built on the north bank because Churchill saw the waterway as a potential line of defence.

Mooring bollards might only be a foot high but, like so much of the canal environment, they have an endearing sculptural quality. Painted black and white to match the lock gates, some look like toadstools or old milk bottles; others resemble ice-cream cones or even pints of Guinness.

ROGER'S TOP TIPS

Explore a local canal

Most people in England and Wales live within five miles of a canal, and your local towpath will be a gateway to a wealth of built and natural heritage. Towpaths are easily accessible and they always lead to interesting places, often providing unexpected views. You could plan a walk that includes a canal-side pub or café, which hopefully will be open (do check beforehand) – dip into canalrivertrust.org.uk for ideas.

Visit a museum

Several museums tell the story of our inland waterways. These include the London Canal Museum near King’s Cross, the National Waterways Museum at Ellesmere Port in Cheshire, the National Waterways Museum in the heart of Gloucester Docks and the Canal Museum at Stoke Bruerne in Northamptonshire. They often host temporary exhibitions.

Take a boat trip

This is a great way to appreciate canal heritage and there are plenty of places where you can take to the water. You could cruise along the Regent’s Canal through the hidden heart of London, or have an on-board venture into the great tunnel next to the Black Country Museum. For a true heritage experience, seek out a horse-drawn canal trip – where the vessel is pulled by a horse, just as it was in past times.

Enjoy an icon

There are eye-catching places to discover, but some are truly iconic and deserve a full day out. For example, the daring Pontcysyllte Aqueduct near Llangollen is a World Heritage Site; the impressive Hatton Locks flight at Warwick is known as the ‘Stairway to Heaven’; and the amazing contemporary Falkirk Wheel in central Scotland is the world’s only rotating boat lift.

Pick up a good book

Narrow Boat by LTC Rolt was first published in 1944 and has remained in print ever since. It describes a four-month canal journey and sparked a revival of interest in our waterways. Titles that specifically look at architectural heritage include Canals by Nigel Crowe and Britain’s Canals by Anthony Burton and Derek Pratt – the latter was published last year. Look at canalbookshop.co.uk for comprehensive listings.

Tap into a useful website

The canal junction website is a good place to discover how to plan a canal holiday.

About the Author

Roger Butler

Roger Butler is a lecturer, writer and photographer with a particular interest in canal heritage. He trained as a geographer and landscape architect and worked as strategic planning manager for British Waterways, where he was responsible for canal restoration projects and environmental improvements across Britain. Roger is a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, a licentiate of The Royal Photographic Society and a chartered member of the Landscape Institute. He writes for a number of magazines and regularly contributes to countryside, canal and heritage titles. His lectures for The Arts Society include Canal History and Heritage, The Hidden World of Canal Architecture and Birmingham – more canals than Venice!

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition