This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on...Oscar Wilde in theatreland

Become an instant expert on...Oscar Wilde in theatreland

14 Nov 2023

Theatre is ‘the greatest of all art forms, the most immediate way in which a human being can share with another the sense of what it is to be a human being’, said Oscar Wilde. Our expert, Simon Whitehouse, reveals the impact the dramatist, writer and wit had on London’s West End

Oscar Wilde photographed by celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony during his lecture tour of America in 1882. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Oscar Wilde photographed by celebrity photographer Napoleon Sarony during his lecture tour of America in 1882. Image: Wikimedia Commons

‘The truth is rarely pure and never simple’

Oscar Wilde

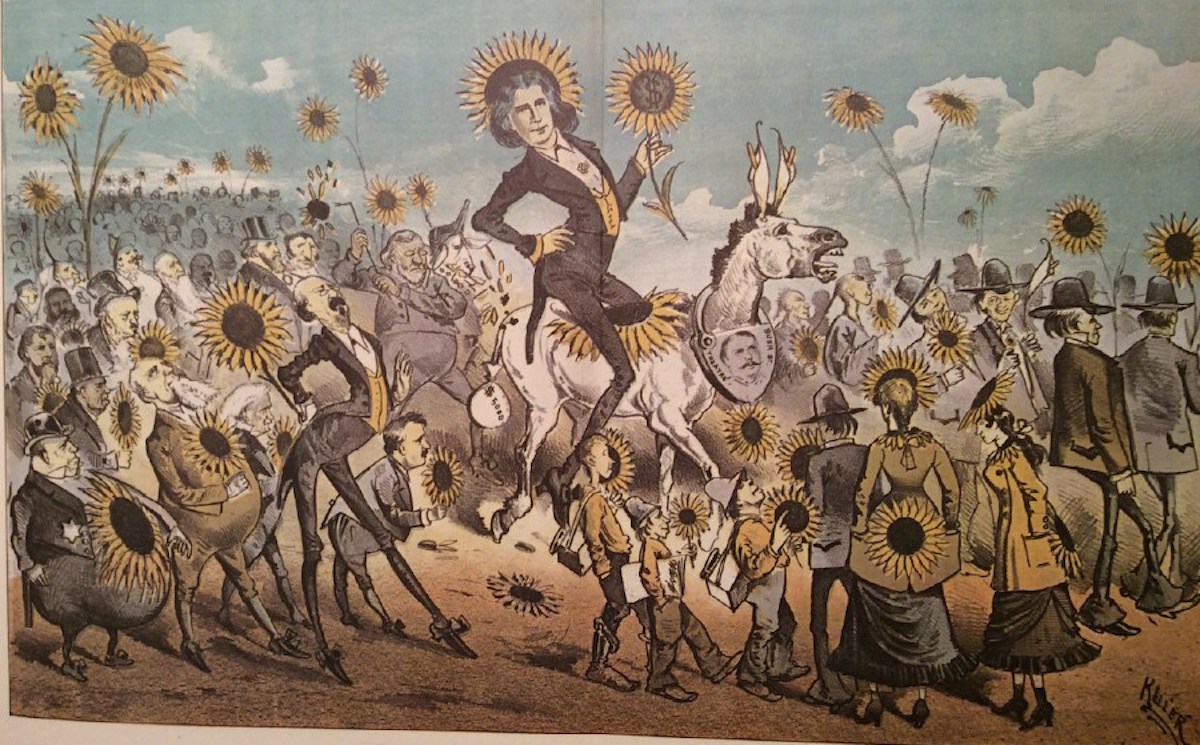

A cartoon from The Wasp, depicting Wilde’s 1882 visit to San Francisco: the sunflower was an emblem of the Aesthetic Movement, which he championed. Image: Wikimedia Commons

A cartoon from The Wasp, depicting Wilde’s 1882 visit to San Francisco: the sunflower was an emblem of the Aesthetic Movement, which he championed. Image: Wikimedia Commons

1. The importance of being Oscar

They say there’s no such thing as an overnight success.

Long before Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) enjoyed theatrical notoriety, he was already a celebrity, famous for the extraordinary way he spoke and dressed. Known as the ‘Apostle of Aestheticism’ he promoted beauty and the idea that all should ‘love art for its own sake and then all things that you need will be added to you’.

So well known was Wilde that he was the inspiration for the principal character of Bunthorne in Gilbert and Sullivan’s operetta Patience, a satire on the Aesthetic Movement. So, in essence, Wilde’s first foray into theatre was as the butt of a joke.

He wrote his first play Vera; or, the Nihilists in 1880; it was a piece about suicidal Russian assassins (and about as much fun as it sounds). It was intended to be premiered in London that same year but was in fact staged first in 1883 at the Union Square Theatre in New York. It closed after a week and is rarely revived.

He then wrote The Duchess of Padua. This also flopped.

Next, Wilde turned his hand to Salome, written for the French actress Sarah Bernhardt. The strict censorship laws of the day, however, led to it being banned by the Lord Chamberlain, because the portrayal of Bible stories and characters on stage was seen as blasphemous.

In the light of all this, having tried his hand at tragedy, Wilde decided to turn to comedy.

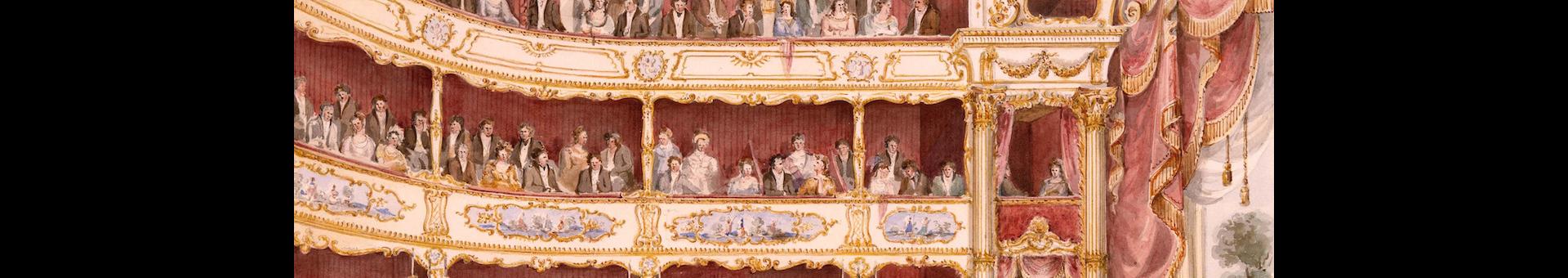

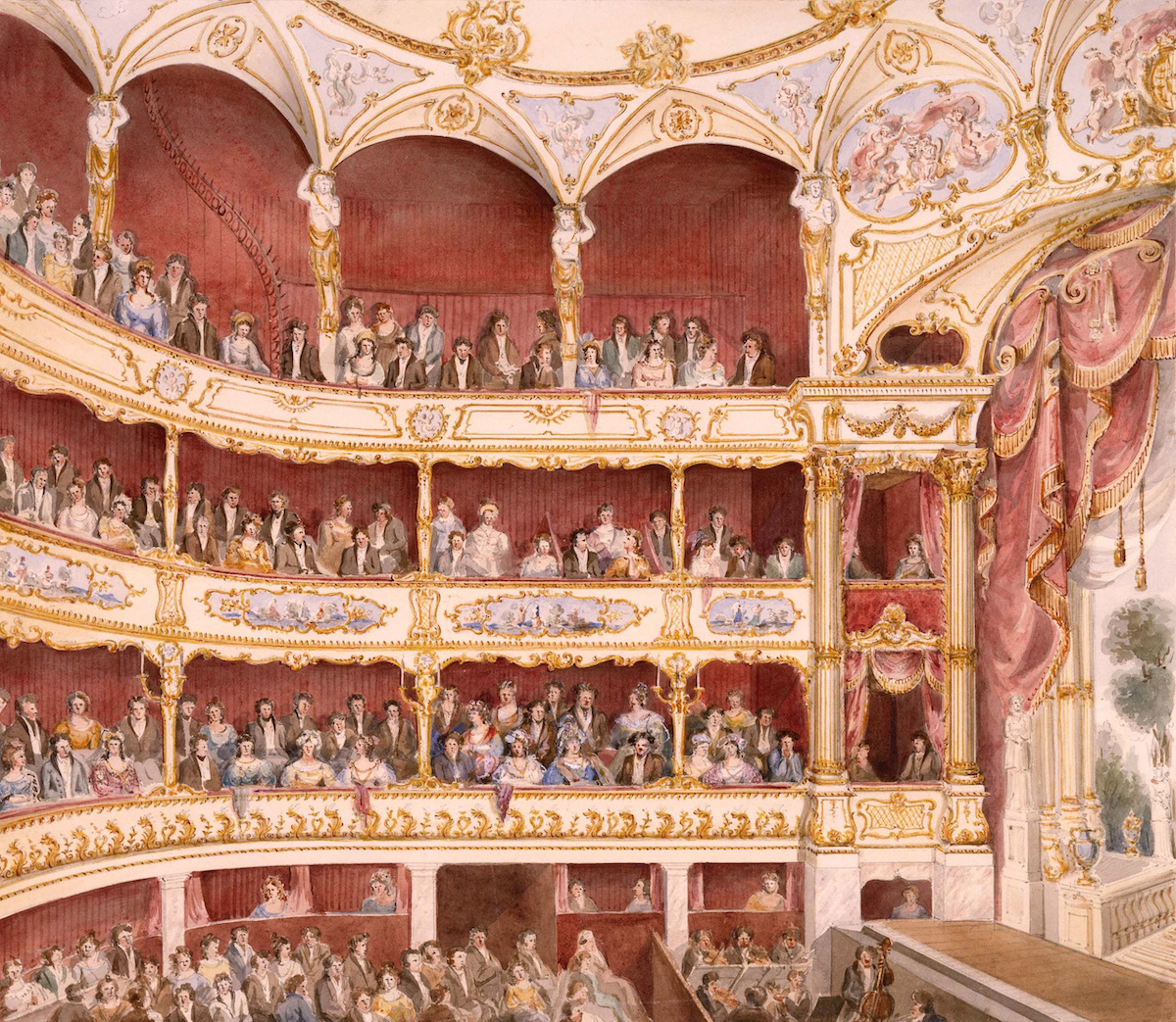

A view of the interior of St James’s Theatre, where Lady Windermere’s Fan was first staged in 1891. This 1835 painting was by John Gregory Crace. Image: Wikipedia

A view of the interior of St James’s Theatre, where Lady Windermere’s Fan was first staged in 1891. This 1835 painting was by John Gregory Crace. Image: Wikipedia

2. Early successes

In the ‘Naughty Nineties’, West End theatres were dominated by actor-managers; it was to two such men that Wilde owed his theatrical success.

The first was the shrewd George Alexander, who persuaded Wilde to write a play for the elegant St James’s Theatre in the fashionable neighbourhood of St James’s. Alexander had taken a gamble by taking the theatre over in 1890. Prior to that, it had not been a particularly successful venue. It had been built in 1835, but in the wrong place (theatre is about location, location, location). St James’s was in too quiet an area, just slightly too distant from other West End stages.

Despite this, Alexander ushered in a golden age for St James’s by introducing the ‘St James play’. These were witty, sophisticated, elegant social comedies, reflecting the world of the audience, with scenes set in fashionable drawing rooms, dinner parties and country house weekends.

In 1891 he persuaded Wilde to write just such a play. By October of that year Lady Windermere’s Fan was complete – the story of a woman who thinks her husband is having an affair with an older woman, who (spoiler alert) turns out to be her own mother, who had abandoned her some 20 years before. This became a common theme in Wilde’s plays, where one or more characters is hiding a shameful secret.

The poster for the opening night (held in the British Library today) gives a glimpse of the theatre-going experience in the 1890s. The statement, ‘This theatre is lighted by electricity’ reminds us electric light was a recent and exciting innovation; only a decade earlier the Savoy Theatre had been the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity.

The play premiered on 20 February 1892 and Alexander starred as Lord Windermere. The production was received warmly and calls for ‘Author!’ saw Wilde appearing on stage and making a wonderfully ironic, egotistical speech. The play ran for 192 performances and, although Alexander had offered Oscar £1,000 in advance, he had opted to take a percentage of the box office instead (a shrewd move), and so netted £7,000 (about £800,000 today) in the first year alone.

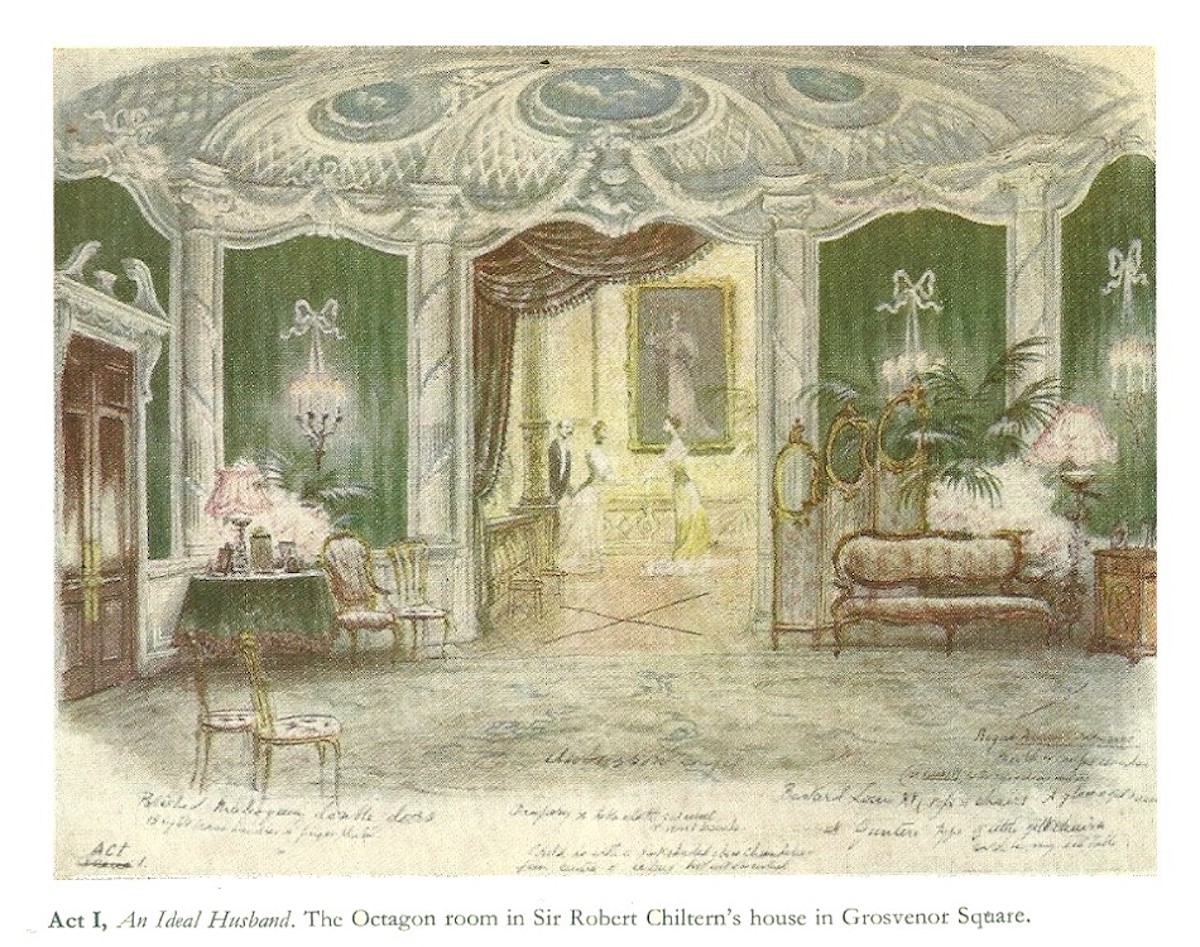

A Rex Whistler stage design for the wartime revival of An Ideal Husband at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket / The Masque – Designs for the Theatre by Rex Whistler. Image: Wikimedia Commons

A Rex Whistler stage design for the wartime revival of An Ideal Husband at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket / The Masque – Designs for the Theatre by Rex Whistler. Image: Wikimedia Commons

3. To the Theatre Royal, Haymarket

In 1892 Wilde was approached to write a new play by another titan of the theatre, the wonderfully named Herbert Beerbohm Tree, for his company at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket.

Entitled A Woman of No Importance, it was another satire on English upper-class morality and double standards. The play centred around Lord Illingworth (played by Tree), a powerful flirt who employs a young man as his secretary. It turns out the man is his son by a woman he seduced 20 years prior, but refused to marry, leaving her to bring the child up alone (you can sense a theme here…).

Incidentally, Tree did so well from these plays that he was able to build a new theatre across the road from the Haymarket – Her (now His) Majesty’s Theatre.

The play ran from April to August 1893; the audience liked it, but the critics were lukewarm. It is seen today as the weakest of the Wilde plays written in the 1890s.

Hot on the heels of this, he wrote another play for the Haymarket called An Ideal Husband. This was a more serious offering, revolving around political corruption, in which a cabinet minister is blackmailed by his wife’s old school friend for having sold a cabinet secret and making a fortune as a result.

Actors Allan Aynesworth, Evelyn Millard, Irene Vanbrugh and George Alexander in the 1895 premier of The Importance of Being Earnest. Image: Wikipedia Commons

Actors Allan Aynesworth, Evelyn Millard, Irene Vanbrugh and George Alexander in the 1895 premier of The Importance of Being Earnest. Image: Wikipedia Commons

4. Triumph and catastrophe

In 1895 George Alexander summoned Wilde to write a second play for the St James’s Theatre – The Importance of Being Earnest. Alexander (who once again starred in the production) forced Wilde to cut his original four acts to three to accommodate the ‘curtain raiser’: a traditionally short, one-act play that preceded the main production.

Described by Wilde as a ‘trivial comedy for serious people’, The Importance of Being Earnest was a perfectly plotted farce (full of misunderstandings) involving two young men: Ernest (whose real name is Jack) and Algernon. The two lead double lives (mirroring Wilde’s own ‘double life’). Very few people in the audience would have realised that ‘being Earnest’ was a euphemism for being queer, which had been illegal since 1885.

In the play’s most famous scene, Wilde gives us one of the most extraordinary characters in English drama: Lady Bracknell. She’s the original ‘Hyacinth Bucket’, or should we say ‘Bouquet’, who interrogates Ernest to assess his suitability for marriage to her daughter Gwendolen. In doing so the shallow, hypocritical nature of Victorian high society is placed in the spotlight. Allan Aynesworth, who played Algernon, recalled: ‘In my fifty-three years of acting, I never remember a greater triumph than [that] first night.’

It turned out to be Wilde’s last play.

Within weeks his name was removed from the posters, and the play closed after 87 performances, as he found himself starring in the most sensational criminal trial of the century.

Found guilty of multiple counts of gross indecency, Wilde was declared bankrupt, incarcerated for two years, then forced to flee to Paris. He died on 30 November 1900 aged 46, believing he was hated and despised, and that his works would be forgotten.

Well, as Algy says to Ernest, ‘The truth is rarely pure and never simple.’

Simon pictured with artist Maggi Hambling’s sculpture A Conversation with Oscar Wilde in London

Simon pictured with artist Maggi Hambling’s sculpture A Conversation with Oscar Wilde in London

5. The aftermath

While Wilde was in exile, George Alexander secured the rights for both Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Importance of Being Earnest. In 1909 he successfully revived the latter at St James’s Theatre, where it ran for 316 performances. This key decision assured the play’s future life and legacy into the 20th century and beyond.

To his great credit, Alexander restored Wilde’s name to the programme and bequeathed the rights to Wilde’s sons as a legacy.

There have been over 300 stage productions since the original and it is (with perhaps the exception of Hamlet) the most produced, quoted and studied play in the English language.

During World War II John Gielgud directed a production of Lady Windermere’s Fan to lift wartime spirits. It remains the most successful production of any Wilde play ever, with a run of nearly two years.

Sadly, St James's Theatre did not survive; it was pulled down in the late 1950s. Happily, John Nash’s 1820 Theatre Royal Haymarket still welcomes audiences today.

On Valentine’s Day 1995, a stained-glass window honouring Wilde was unveiled in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, exactly 100 years to the day of the premiere of The Importance of Being Earnest.

In the heart of London’s theatreland you can also find a sculpture by Maggi Hambling entitled A Conversation with Oscar Wilde (1998). Fashioned in the form of a sarcophagus with Wilde laughing and smoking, it is inscribed with a quotation from Lady Windermere’s Fan: 'We are all in the gutter but some of us are looking at the stars.’

Wilde certainly sprinkled stardust across theatreland, and although we find ourselves more than a century on from his heyday, his talent and genius shine ever brighter.

Simon’s top tips:

Get together with a group of like-minded friends and read the plays out loud to remind yourself of Wilde’s gift.

Watch Stephen Fry’s brilliant portrayal of Oscar Wilde in the 1997 film Wilde.

For a deep dive into Wilde’s life listen to or read the magisterial biography Oscar: A Life by Matthew Sturgis (2018).

Read Rupert Everett’s brilliant memoir of his attempt to make a film of the last years of Oscar’s life, To the End of the World: Travels With Oscar Wilde (2020).

Join the Oscar Wilde Society (see oscarwildesociety.co.uk)

Walk in the footsteps of Oscar Wilde on a Wilde walk with me around the West End to visit some of the locations and explore the stories featured in this ‘Instant Expert’.

Our expert’s story

Simon Whitehouse is a (recovering) actor, lecturer and presenter, and Alexander Technique and voice teacher; he is also an award-winning London Blue Badge guide. He regularly guides for The Arts Society groups in addition to his lecture offerings. He has worked as a guide and lecturer in-house at Shakespeare’s Globe, the Royal Opera House, the BBC and the National Gallery. He is on the faculty of Ithaca College and also lectures for the Blue Badge guide training course on the performing arts and English literature modules. Simon’s specialisms and passions are theatre, literature, fashion and art history. Among his talks for The Arts Society are (on Wilde): Wilde about Oscar: famous for being famous (and infamous); (on Wilde’s plays): A Haaaand-baaaag? The importance of being Oscar – and Earnest; and (on Wilde’s downfall): The Trials of Oscar Wilde. These talks can be combined as a Study Day. Other lectures include Artistic and Literary Chelsea, The world’s greatest paintings: 200 years of the National Gallery and Punch, Pineapples and Pygmalion: a short history of Covent Garden.

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition