This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on...Oleksandr Bohomazov, the ‘lost’ Futurist artist of Ukraine

Become an instant expert on...Oleksandr Bohomazov, the ‘lost’ Futurist artist of Ukraine

21 May 2024

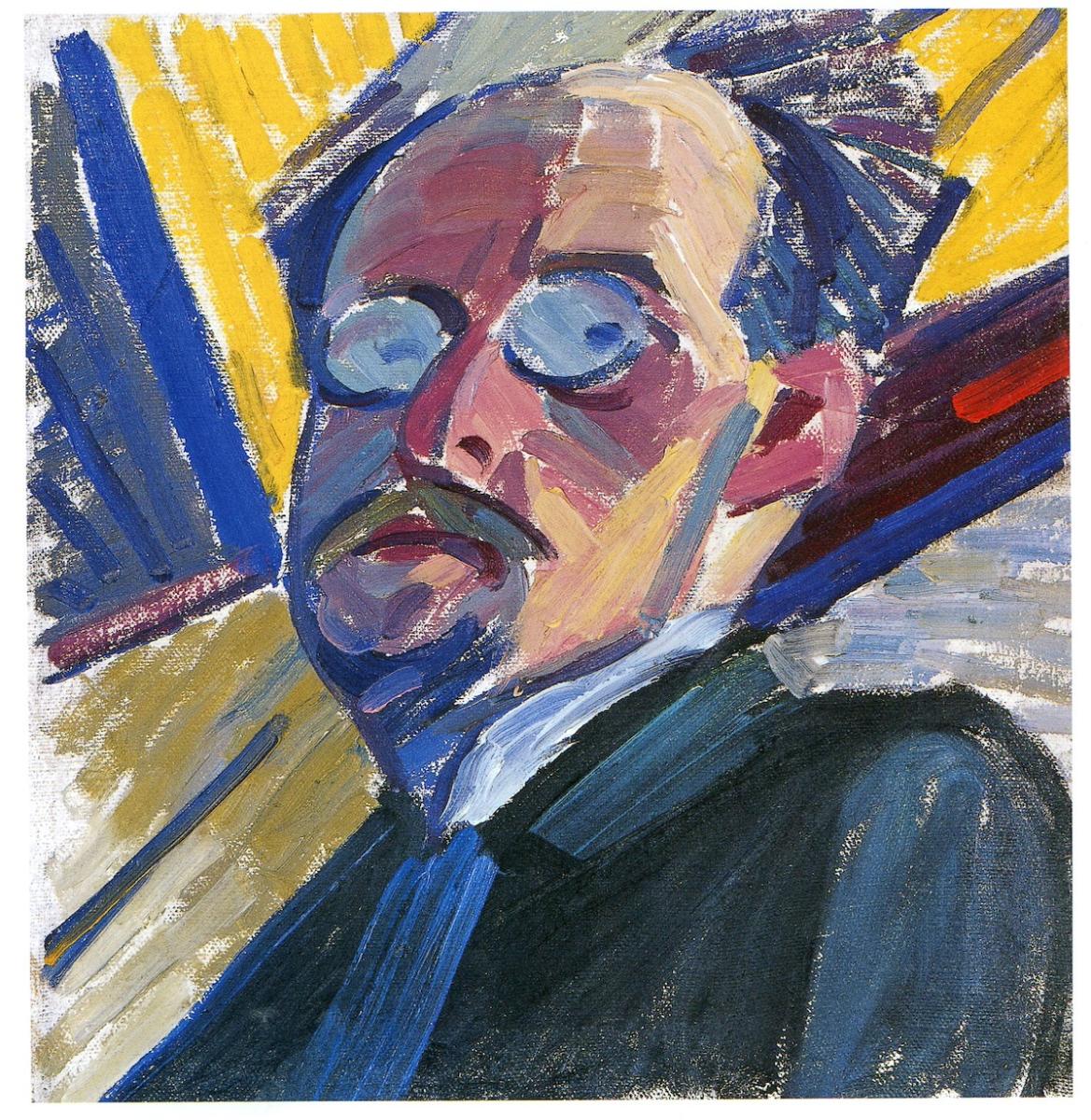

Oleksandr Bohomazov was a pioneer of early 20th-century Ukrainian avant-garde. Yet despite his standing in the arts his name, until recent times, has been lost in history. Our expert, James Butterwick, explores the story of his art, life and powerful relationship with the woman who unlocked his creativity and saved his legacy

Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880-1930) Self Portrait 1914-15 / Image: James Butterwick Collection, London

1. A search for love

Oleksandr Bohomazov’s beginning in life was not easy and his troubles were to deeply impact his life as an artist.

He was born in 1880 near Sumy in East Ukraine into a house at odds with conservative Orthodox tradition. His mother walked out on the family when he was an infant. Bohomazov’s daughter, Yaroslavla, later recalled: ‘she fell in love with someone else and abandoned my grandfather with two children. He banned any mention of her name.’ Bohomazov was himself to write: ‘as for father, we kept our distance from him. We feared him. We were strangers.’

The child, lacking in affection, became fragile and introspective, constantly seeking the love he had not been given. He set out on a career in art without the support of his father. In doing so, in 1908, he met a fellow student at the Academy of Arts in Kyiv – the bohemian Wanda Monastyrska. He fell for her, hook, line and sinker.

‘I love everything about her’, he wrote, ‘how fine and tender she is. I will always love her. She has filled my soul. My art has retreated, a woman has come and closed it from my eyes… my art is in the woman – in this beautiful particle of the world.’ The two were interdependent: Bohomazov’s art and his creativity as an artist could only, it seems, be fulfilled if this woman returned his feelings.

Bohomazov’s Wanda in front of a New Year Tree, (detail) 1911-12 / Image: James Butterwick Collection, London

Bohomazov’s Wanda in front of a New Year Tree, (detail) 1911-12 / Image: James Butterwick Collection, London

2. Rejection and relent

His love was not returned. The rejection was tortuous.

Wanda, unlike Bohomazov, was from a warm and loving family and found the gangly, maladroit artist odd, even eccentric. Clearly, though, she gave him permission to paint her and to correspond.

Early representations show a Wanda distant from the artist; the eyes never connect and she is an abstract. Bohomazov would ‘surprise’ her by hiding behind trees at the Academy, feigning surprise at her appearance and then walking her home. His letters to her are poetic, while a drawing from a trip to Finland in 1911 is dedicated to her. ‘(Lake) Saima made a noise and, listening to her melodies, I thought of you’, reads the touching inscription.

Fortunately for Bohomazov, by the new year of 1911–1912, Wanda began to thaw. Her new year portrait (above) shows her engaging with the artist for the first time, but in a reserved fashion. Her gaze is turned, she is interacting, but her eyes, her suspicious glance, betrays her. This was to change, radically.

Caucasus, undulating landscape, 1915-16 by Oleksandr Bohomazov, which will be on show this June at the Royal Academy of Arts, London / Image: Collection of Michael and Ellen Ringier, Zurich

Caucasus, undulating landscape, 1915-16 by Oleksandr Bohomazov, which will be on show this June at the Royal Academy of Arts, London / Image: Collection of Michael and Ellen Ringier, Zurich

3. Creativity unleashed

‘Wanda told me how she spent five years working him out and analysing him. Then she got used to him and fell in love with him. Forever.’ This was art historian Professor Dmytro Horbachov, a specialist on the Ukrainian avant-garde, writing later. In 1965 he had rediscovered Bohomazov’s work, through meeting Wanda, who was living in the same tiny flat overlooking the Academy of the Arts that she had occupied since before World War I.

But to return to earlier years, by 1913 Bohomazov’s ardent pursuit of Wanda had born fruit; the pair were married in August in Boyarka, outside Kyiv. In their wedding portrait they look reserved, distant from one another. Yet, as Bohomazov wrote, ‘the mystery of spiritual marriage has been made by the twinkling stars in their depths. Fate has tied the knot of my existence to this subtle, exquisite, good, sensible girl’.

This seismic event set off an ‘explosion of creativity’ within him. It set him on a new path, unencumbered by emotional anguish, to a new language of Futurism, the equal of his European contemporaries, whose work he never saw.

Before the outbreak of war, in August 1914, Bohomazov finished his theoretical treatise Painting and Elements – a revolutionary insight into the psychology facing both artist and individual. Today this sits in the Central State Archive-Museum of Literature and Art of Ukraine in Kyiv. Dedicated to Wanda, ‘his faithful, lifelong companion’, the paper has yet to be analysed in detail, but has been described by the few who have read it as ground-breaking. Its theories pre-date some of those espoused by both the avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich, and the pioneer of abstraction in western art, Wassily Kandinsky.

Despite his artistic progress Bohomazov continued to be permanently impecunious so, in 1915, he travelled to South Caucasus to take up a teaching post at a local school. There, he was inspired by the landscape.

‘The mountains are like a giant funnel, where grandiose volumes have twisted crashed and collided’, he wrote the following year, as he embarked on a brief period of creativity quite unique in the western art canon. ‘Painting is like a fine surgical operation where everything is based on precise judgement and knowledge’, he continued later, while pouring his considerable energies into a series of landscapes.

The dynamics of nature fascinated the artist who, in the artistic language of Italian Futurists Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni created canvasses that combined violent movement with vibrant colour inspired by Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), whose work he had seen in Moscow in 1906.

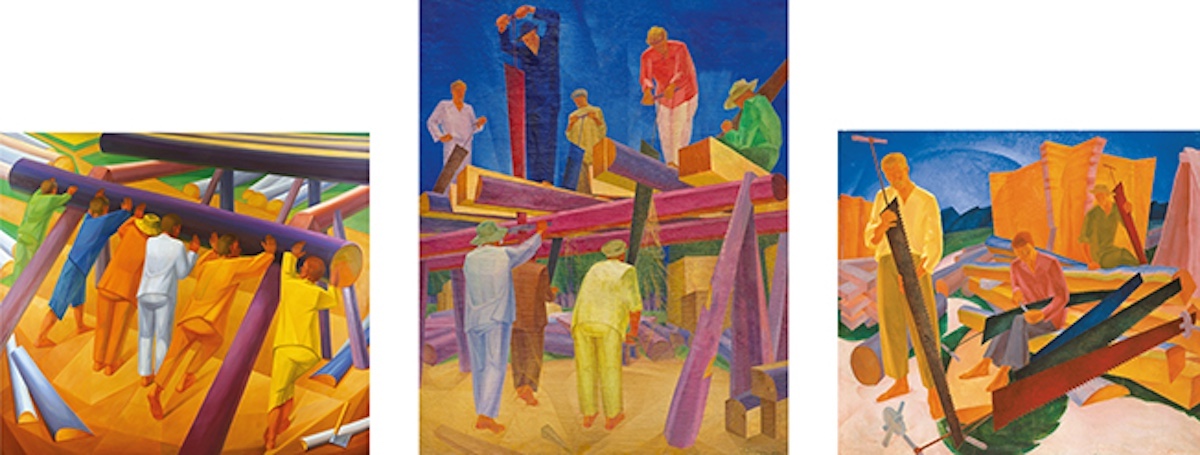

Bohomazov’s triptych, with reconstructed left panel, Rolling the Logs, 1926-1929 / Image: James Butterwick Collection, London and the National Art Museum of Ukraine

Bohomazov’s triptych, with reconstructed left panel, Rolling the Logs, 1926-1929 / Image: James Butterwick Collection, London and the National Art Museum of Ukraine

4. Revolution, illness and a triptych

In late 1916 Bohomazov returned to Kyiv. There he was overtaken by the events of the 1917 revolution and personal tragedy.

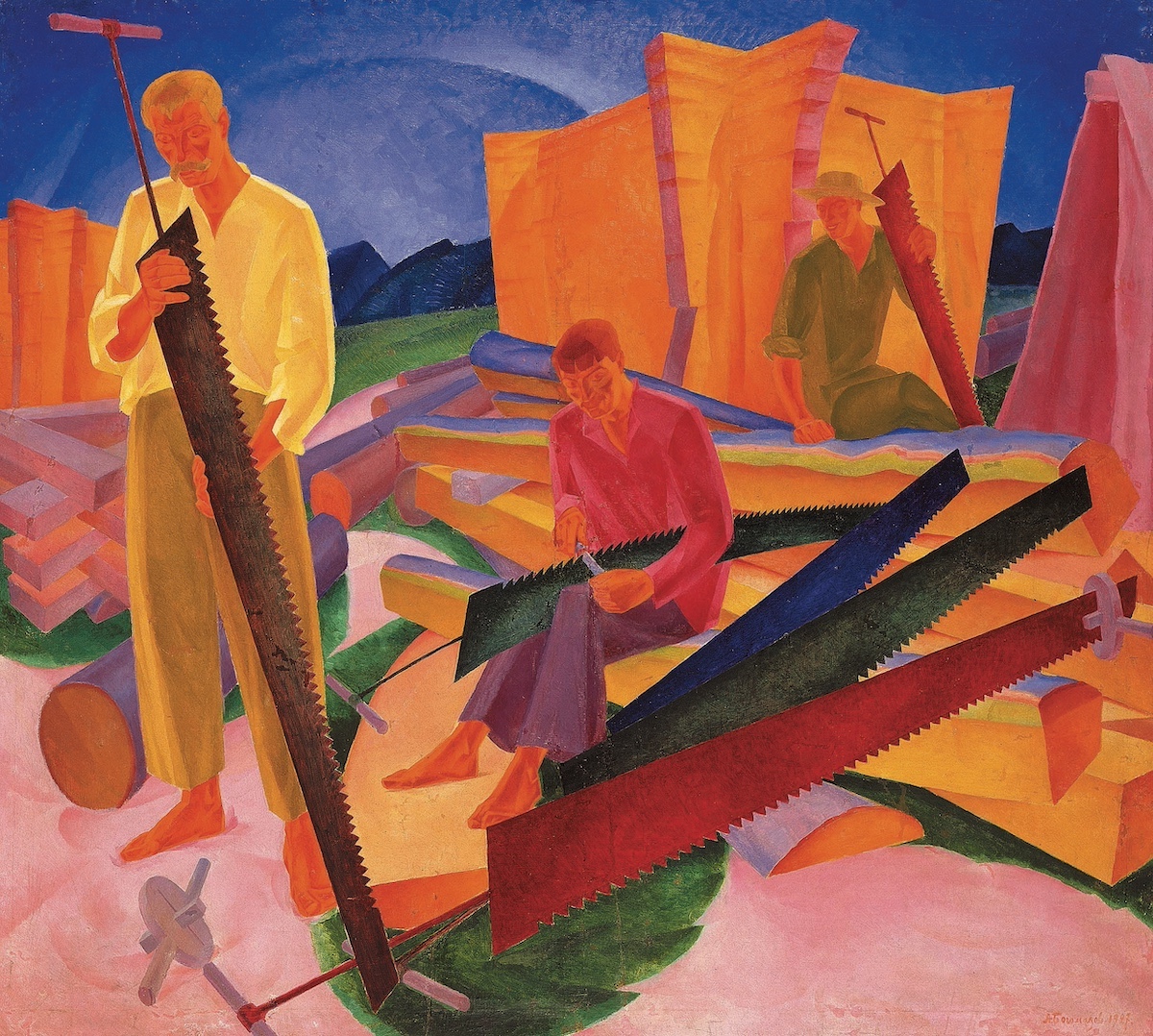

Hiding out in the city of Boyarka (some 20 km from Kyiv) from the civil war raging in Ukraine he contracted tuberculosis in 1920. The disease left him acutely aware of the imminence of his death and, after an eight-year period of inactivity from 1917, he embarked on a triptych that, he hoped, would be his artistic legacy.

Sadly this monumental work was to be interrupted by illness and financial and personal hardship; it was never completed. Bohomazov succumbed to tuberculosis on June 7th, 1930, aged 50.

The work for this project, consisting of over 300 studies, was only understood to be a triptych by art historian Elena Kashuba in 2014.

The right-hand section, Sharpening the Saws, always formed part of the permanent display at the National Art Museum of Ukraine. The central section, The Work of Sawyers, lay forgotten in the reserve collection and fell into disrepair. A four-year restoration project began in 2015 and the painting was returned to its original state. The left-hand section, Rolling the Logs, was never begun. Studies remain, however, and in 2019 the James Butterwick Gallery commissioned a life-size replica, now held in a private home.

A detail of Bohomazov’s triptych, Sharpening the Saws, 1927, to be seen in the exhibition In the eye of the Storm, Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s (details in the ‘top tips’ section below) / Image: National Art Museum of Ukraine

A detail of Bohomazov’s triptych, Sharpening the Saws, 1927, to be seen in the exhibition In the eye of the Storm, Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s (details in the ‘top tips’ section below) / Image: National Art Museum of Ukraine

5. A legacy saved

The tragedy of Bohomazov did not end with his death, as Soviet repression put paid to a nascent revival of Ukrainian culture. Such subversive and individualistic art as that of Bohomazov could only be regarded with suspicion by the new regime, and so Wanda hid her husband’s work in a large trunk.

Then, in World War II, when German troops under Hitler’s rule marched into Kyiv in 1941, the frail Wanda (who was under five-foot tall) pushed the trunk on a wheelbarrow to hide it 15 km away, with relatives in Svyatoshino. She returned in 1944 when the city was liberated, to complete the trip in the other direction. This indomitable woman was responsible for saving the entire legacy of her husband. She outlived him by over 50 years, enough to see the first exhibition devoted to his works in the city in 1966.

When Ukraine declared independence in 1991, the first exhibition staged by the National Art Museum of Ukraine was a comprehensive retrospective of work by this pivotal figure in the history of the country’s art. Today his works are held in private and public collections, including at MOMA in New York and the Kröller Müller Museum, Netherlands. I first came across his art at the Barbican Art Gallery in 1988 at an exhibition of Russian art from Soviet private collections. I was blown away by the quality of his work; he was an artist who did not suffer from comparisons with his contemporaries Kazimir Malevich, Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky. I have spent a large part of my career in the art world bringing Bohomazov’s story to a western audience. His is a shining light in the story of Ukrainian art. He was one of the most influential experimentalists of that country’s avant-garde, and it’s heartening to see his art now receive the recognition it deserves.

James’s top tips

See

Visit the Belvedere Museum in Vienna where a ground-breaking exhibition, In the eye of the Storm, Modernism in Ukraine 1900-1930s, is showing until 2 June, 2024. The exhibition features eight works by Oleksandr Bohomazov.

The same exhibition (a smaller version) will be at the Royal Academy of Arts, London from 29 June – 13 October 2024.

Read

There is no comprehensive book on the artist to date, but there are exhibition catalogues. Four of these are on my website at jamesbutterwick.com (specifically see jamesbutterwick.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Alexander-Bogomazov-TEFAF-2016.pdf ). This features in-depth interviews with family members, Professor Dmytro Horbachov and articles on the importance of Bohomazov.

You may notice different spellings of the artists’ name and surname. At the request of Ukrainian colleagues, these were changed from ‘Alexander Bogomazov’ to reflect his true origins.

Take a view

When viewing the artist’s work it’s helpful to know that he never, unlike the majority of his contemporaries, travelled outside the borders of the Russian, or Soviet, empires. He left Kyiv only three times to go to Moscow, Finland, then part of Russia, and the Caucasus.

James Butterwick at ‘Radio Culture’, Kyiv

James Butterwick at ‘Radio Culture’, Kyiv

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

About the Author

James Butterwick

is a leading expert on Russian and Ukrainian art. He has curated four exhibitions of works by Oleksandr Bohomazov, as well as exhibitions devoted to Ukrainian Futurism. His own private gallery, James Butterwick Gallery in London, specialises in Russian, Ukrainian and European works. His current talks for The Arts Society include Oleksandr Bohomazov, 1880-1930: the lost Futurist of Ukraine and The dark side of the boom: the mass faking of the Soviet avant garde highlighted in a recent BBC4 TV documentary The Zaks Affair.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition