This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on Great British Piers

Become an Instant Expert on Great British Piers

7 Jul 2021

The British coastline was once dotted with 100 piers; today a little over half survive. But those survivors still rule the waves, says our expert, Jackie Marsh-Hobbs, and are a powerful reminder of the ingenuity of the figures who built them

The West Pier at Brighton, c.1880

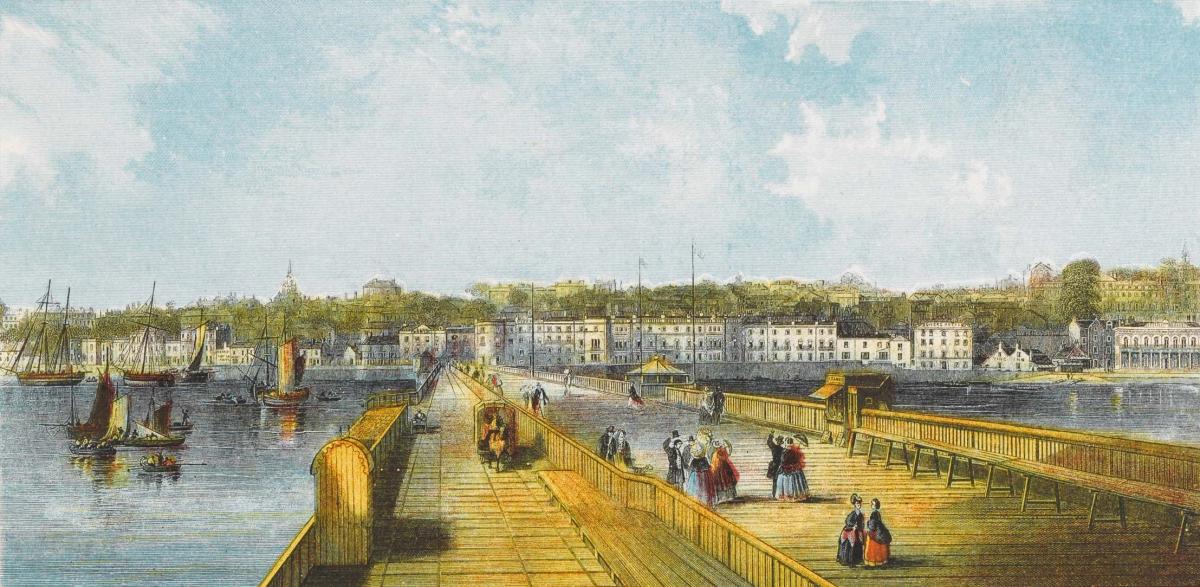

Ryde on the Isle of Wight, seen from its pier in the 1850s

1. FROM THE BEGINNING...

On 26 July 1814, the first pleasure pier opened at Ryde on the Isle of Wight.

At 1,740 feet (530 metres) long, the new wooden structure was built to be used as a landing stage – or a place to promenade, for the price of two old pennies. There was a toll of threepence for people arriving or embarking on the pier, and an extra shilling if they came by four-wheeled carriage. The cost for landing or exporting livestock ranged from sixpence for a bull or a cow, down to a penny for a sheep.

In the 1820s the development of piers evolved, with two elegant suspension piers opened, both designed by engineer Captain Samuel Brown. The first was the Trinity Chain Pier, at Leith in Edinburgh (1821), followed by the Chain Pier at Brighton (1823), which both Turner and Constable committed to canvas.

Over the next decade six more wooden piers were built at Southend, Southampton, Gravesend, Herne Bay, Walton-on-the-Naze and Deal.

Building a pier was a huge undertaking. A company had to be set up, investors found, shares sold for the money needed and, critically, an engineer with the right experience employed. It also required an Act of Parliament and local permission to build on the foreshore and out to sea.

The hope was that the building – a true feat of engineering – would not be hindered by storm damage or other delays. Consequently, more piers were planned than ever came to fruition.

Among the many benefits for the up-and-coming seaside resorts that got a pier was the fact that paddle steamers could now bring more visitors to their sites, with the knock-on upturn in their economy.

Looking out from the balcony of the 1893 pavilion on Clacton-on-Sea’s pier, with its ornate ironwork

2. IRON PIERS AND ORNAMENTATION

The building of railways – and the 1844 reduction of fares – enabled even more people to visit the seaside. In addition, engineers who worked on the railways – such as Eugenius Birch, who designed the first iron pier in Margate in 1855 – had an impact, bringing their expertise to pier building. Big changes happened with the building of that pier at Margate. Instead of wooden piles, Birch used iron screw ones, which had been patented and invented by the remarkable blind Irish engineer Alexander Mitchell.

Iron pier construction entailed pounding piles or screwing those iron screw piles into the seabed, their robustness bringing stability. Cross-tie bracing connected the piles, which helped stability yet more, while allowing the waves to move through the underneath of the pier. Lattice girders also connected the piles, making a strong platform where the joists could be fixed to support the decking. Hardwood was used for the latter, with a small gap between the planks to let the rain drain through, and to allow for movement in the structure.

The piers were also structures of beauty. Cast iron was versatile as a decorative medium, offering fine detailing in all kinds of styles, and was used on railings, seating and lighting. Ornate details on toll houses, seat shelters, bandstands and kiosks were added to embellish existing or new piers. The combination of cast iron, wood and glass was also used in larger pier buildings. Engineers favoured foundries and contractors that they had worked with before, like Laidlaw & Sons from Glasgow, Head Wrightson of Stockton, and Mayoh and Haley from Manchester, who built Weston-Super-Mare Grand, Morecambe West End and Penarth piers.

The Art Deco pier at Penarth in Wales

3. STYLE AND ENTERTAINMENT

With more holidaymakers visiting the coast and demand for attractions rising, the 1860s and 1870s were the most productive in pier building. The British seaside pier truly arrived in all its splendour, with magnificent palaces and pavilions emphasising that they were places to delight.

Seaside Orientalism inspired buildings such as the large pavilion on Morecambe’s Central Pier. Bournemouth Pier’s original entrance building welcomed visitors with its ornate Gothic-style clock tower. Still standing is the 1935 Moderne Southern Pavilion on Worthing Pier, and the sleek Art Deco pavilion on Penarth’s pier.

In such stylish settings, entertainment on piers had a special element, or edge, to it. The early bands played in the open air with the sound of the waves beneath. And today there is the continued, added drama of reaching a theatre at the head of a pier via a bracing walk, and hearing the wind, rain and sea during a show. Old posters, newspaper cuttings and records show some theatres had performances throughout the year.

Music hall stars like Marie Lloyd and George Robey, touring Pierrots and concert parties all appeared. The 1920s and 1930s brought comedians Arthur Askey and the sister duo Elsie and Doris Waters. Many who went on to become household names learnt the ropes of their profession working pier theatres, among them Bruce Forsyth, Barbara Windsor, Morecambe and Wise, Ken Dodd and Cannon and Ball. Past performers on Hastings Pier alone include Georgie Fame, Dusty Springfield, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Pink Floyd and Cilla Black.

Today, only five piers still have working theatres: Blackpool North, Worthing, Weymouth, the Britannia at Great Yarmouth and Cromer Pier.

The long-gone Victoria Pier, Folkestone, pictured in its heyday in the 19th century

4. DISAPPEARING HERITAGE

It is evident in railway posters, guidebooks, brochures and publicity films that seaside resorts regarded their piers as vital attractions. But times moved on and these special landmarks, inevitably, felt the impact of change.

In 1940 many of our piers on the east and south coast were breached to stop them being used as landing stages in wartime. The Navy used Southend, Folkestone and Cowes Victoria on the Isle of Wight, while Minehead’s pier was removed to give a line of fire for gun placements.

Years of neglect meant major work was needed before the closed piers could be reopened after the war. Some piers become shorter, while others simply did not survive at all.

Through the late 1940s and into the 1960s summer holidays had meant the seaside. Harking back to wakes weeks (when factories closed to enable workers a holiday) and day excursions, people still headed to coastal holiday camps and caravans. But increased air travel and cheaper holidays abroad took visitors away from British resorts. Fewer tourists made it difficult to maintain attractions, including piers.

As unique structures built in the sea, piers have to be maintained to give them a chance of standing up to the constant hazards of storm, fire or damage by boats. In 1978, Margate, Hunstanton and Morecambe’s West End Pier were lost, while New Brighton Pier had been demolished the year before.

With alarm raised for the future of our piers, the National Piers Society was founded the following year, with Sir John Betjeman as its first honorary president. Its aims were and are ‘to promote and sustain interest in the preservation, building and continued enjoyment of seaside piers’.

Clevedon Pier on a misty morning

5. CELEBRATING THE SURVIVORS

The expense of maintaining a pier, with enough money coming in to make it viable, is a challenge, even for the more successful piers. As seasonal businesses, bad weather is an enemy. The Covid-19 pandemic has also, as with all arts and culture venues, had a huge impact. It is difficult for our piers to recoup losses. Ownership belongs, in the main, to private businesses. This is closely followed by councils and a few trusts, such as the Swanage Pier Trust, which relies on volunteers, donations and fundraising. In addition to a café and shop, and a small toll for visitors, fishing and boat travellers, it costs approximately £200,000 a year to keep this delightful pier going.

The piers that survive continue to hold a special place in the hearts of the public – and the National Piers Society works hard to champion them.

As voted by its members, Pier of the Year 2021 is Clevedon, of which Sir John Betjeman said in his speech at the 1980 public inquiry on its fate: ‘It recalls a painting by Turner, or an etching by Whistler or Sickert, or even a Japanese print… without its pier Clevedon would be a diamond with a flaw.’ In second place comes Llandudno, with Cromer Pier coming in third.

Every one of our surviving 61 piers is special, from the longest pier in the world – Southend, at 1.34 miles – to the shortest, Burnham-on-Sea at 37 metres, to the last pier to be built, in 1957, at Deal. It was done so as a replacement for the World War II-damaged pier.

Today, as in the past, our piers offer colourful experiences.

You can take a trip on Waverley, the last seagoing paddle steamer in the world, which offers cruises from over 50 ports and piers in several parts of the UK. You might choose to take a train ride on Southend, Ryde and Hythe piers. At Southwold you can visit Tim Hunkin’s quirky Under the Pier Show of inventive machines, or at Bournemouth you can zip wire from the head of the pier to the beach. At Clacton-on-Sea and Blackpool’s Central and South piers there’s the whirl of the funfair.

If it’s a connection with nature that you seek, then what can be better than viewing the murmurations around Aberystwyth’s pier?

There are so many exciting piers to explore, each one utterly unique, and all with breathtaking views out to sea.

Brighton’s West Pier 1866 kiosk, rescued from the pier in the 1990s; once restored it will return to the seafront as an education centre

JACKIE'S TOP TIPS

Find out more

The National Piers Society has information on all of our surviving and lost piers and sells books on the subject.

Discover more about the Waverley paddle steamer, which, like many cultural attractions, has been affected by the impact of the pandemic.

Visit Southend Pier Museum on the land end of the pier.

Books to read

The Architecture of British Seaside Piers by Fred Gray (The Crowood Press, 2020)

British Seaside Piers by Anthony Wills and Tim Phillips (English Heritage, 2014)

Martin Easdown is an expert on piers and has authored and co-authored books on piers in different areas of Britain including Piers of Wales, Piers of Sussex, Piers of Kent and Piers of Hampshire & the Isle of Wight (Amberley Publishing, The History Press, Tempus Publishing Limited and Amberley Publishing respectively)

British Seaside Piers by Chris Mawson and Richard Riding (Hersham, 2008), with vintage aerial photographs of piers

See

Pierdom by Simon Roberts: beautiful photographs of piers taken from 2011–14

About the Author

Jackie Marsh-Hobbs

Jackie Marsh-Hobbs has been an Arts Society Accredited Lecturer since 2004. For 21 years she has worked as a guide and in education at the Royal Pavilion and Brighton Museum. Her love of piers stems from her childhood; her parents worked on the West Pier, where, as a young man, her father ran the fishing and tackle shop. She was brought up with stories of the West Pier being an exciting place to work. Among her lectures for The Arts Society are A Passion for Piers, The British Seaside Holiday and The Art of Sea Bathing.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition