This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on Frida Kahlo

Become an Instant Expert on Frida Kahlo

1 Oct 2021

Enigmatic and brilliant, the artist Frida Kahlo presented physically as a living artwork, while describing herself as ‘the great concealer’. Our expert, Fiona Rose, reveals five things you should know about the real Kahlo.

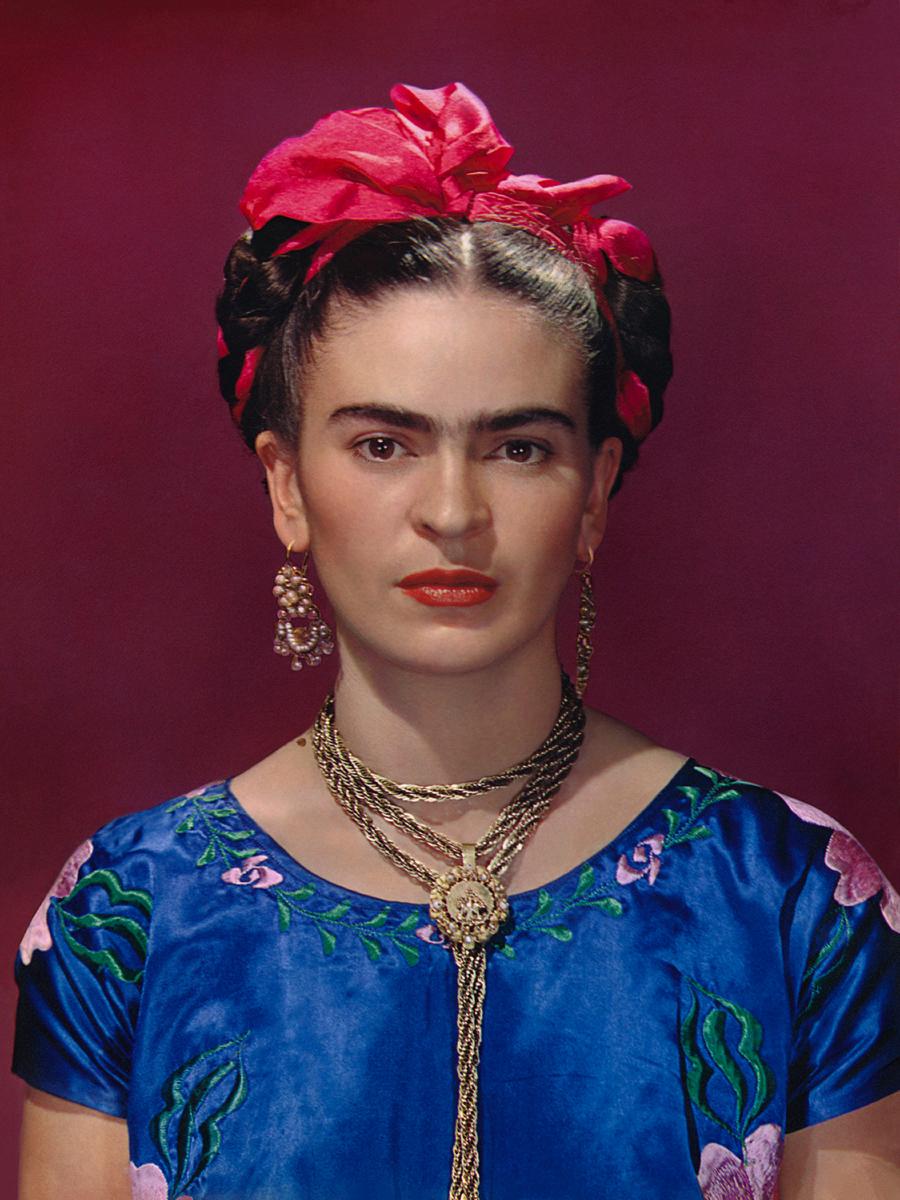

Nickolas Muray’s photographic portrait, Frida Kahlo in blue blouse, 1939

1. IDENTITY AND SKILL

Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón – better known as Frida Kahlo – was born on 6 July 1907 at La Casa Azul (the Blue House) in Coyoacán, Mexico City.

Her father, Guillermo, was from Germany and was an artist – a photographer by profession. Kahlo’s mother, Matilde, was from the Oaxaca region of Mexico.

Kahlo identified with her mother’s indigenous roots, changing the Germanic spelling of her name by losing the ‘e’ and altering the date of her birth to 1910, to coincide with the start of the Mexican Revolution.

‘THEY THOUGHT I WAS A SURREALIST, BUT I WASN'T. I NEVER PAINTED DREAMS. I PAINTED MY OWN REALITY’

– Frida Kahlo, Time magazine, 27 April 1953

Guillermo taught his teenage daughter how to use a camera and develop and retouch photographs. Kahlo also attended drawing classes given by a friend of her father. But she had no early inclination to pursue art as a career; indeed she wanted to become a doctor. She’d had first-hand experience of ill health from a young age. Some researchers believe she was born with spina bifida, a condition that affects the development of the spinal column. We do know that she contracted polio aged six, which left her right leg thinner and shorter than her left.

Then an accident, in September 1925, changed Kahlo’s life forever.

Travelling home from school, her bus collided with a tram. A steel handrail literally skewered her body through the lower abdomen. She suffered horrific injuries, including spinal and pelvic breaks and a crushed foot; her doctors did not think she would live, but they underestimated her extraordinary capacity for endurance and her will to survive.

Kahlo then had the first of over 30 operations, which brought only temporary relief from pain. From her recovery bed she started to paint, using her father’s brushes and oils. A mirror was affixed to the underside of her bed’s canopy. She became her own model, beginning the self-portraits that were to dominate her work.

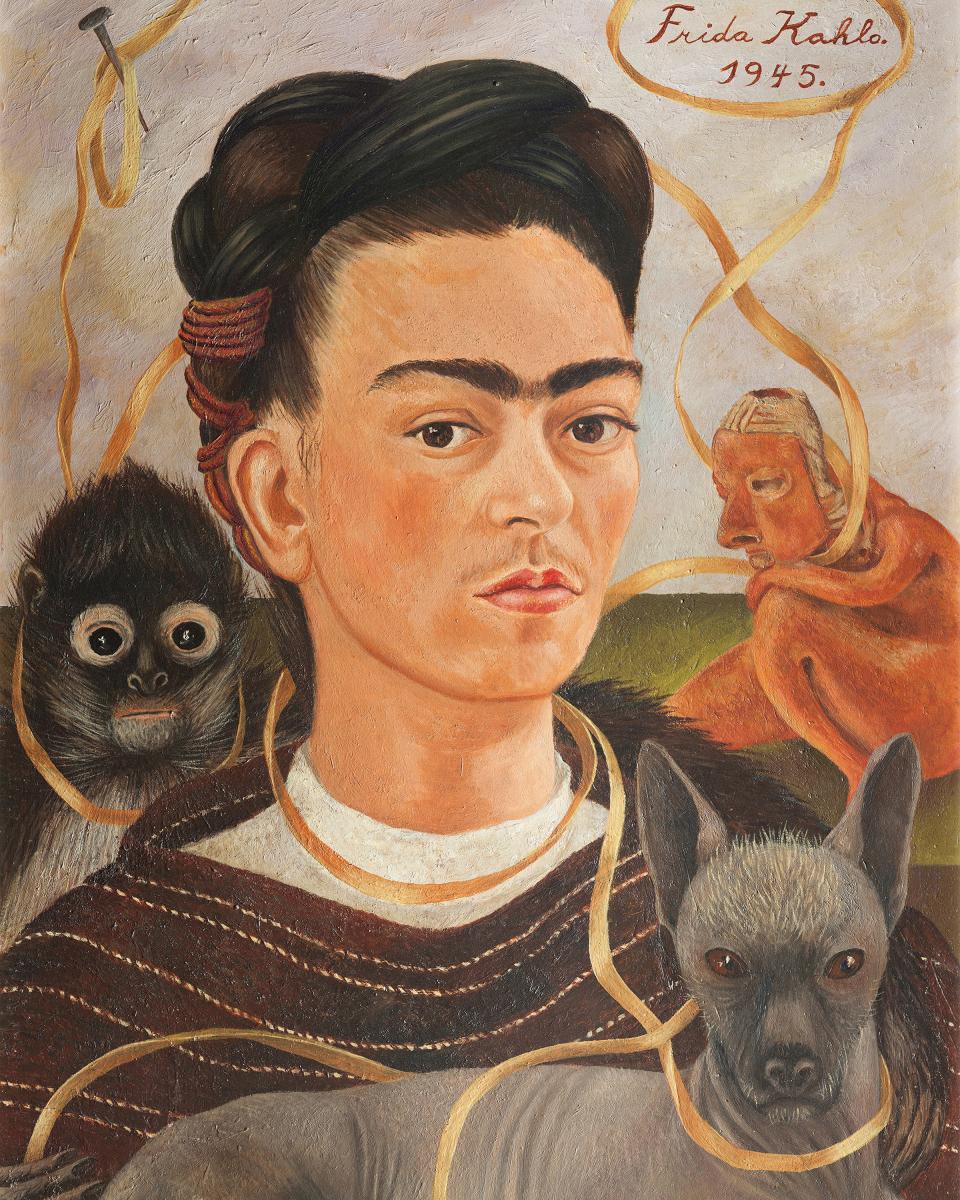

Self-Portrait with Small Monkey, oil on masonite, painted in 1945

2. 'I AM THE SUBJECT I KNOW BEST'

Kahlo emerged from her recovery bed determined to pursue a life of art.

She began mixing with an intellectual and artistic crowd. She joined the Mexican Communist Party and met her future husband, the artist and mural painter Diego Rivera. Outwardly they appeared an odd couple: Rivera was 20 years older and 200lb heavier than Kahlo, with a reputation as a womaniser.

Self-portraits became a dominant theme in her work: of around 200 paintings and drawings, 55 are self-portraits. There was a practical – as well as artistic – reason behind this. Kahlo’s precarious health resulted in long periods of confinement and isolation. Thus, she became her own model, explaining: ‘I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best.'

Her self-portraits allowed her to explore her identity and they became a form of self-expression. Kahlo called herself ‘the great concealer’ and in her works she adopts the same stoic mask-like gaze, her feelings alluding the viewer.

To express her emotions she used symbols, which, when decoded, offer insight into her world. Self-Portrait with Small Monkey makes reference to her indigenismo politics, with the meandering ribbon representing the cyclical connection between humans and the natural world. Kahlo's affinity with her native roots is emphasised by the presence of her hairless Mexican pet dog, the pre-Columbian artefact, and her clothing and hairstyle, which are reminiscent of Tehuantepec, a municipality of Mexico with a matriarchal society.

Kahlo’s oil on metal Henry Ford Hospital, painted in 1932

3. THE IMPORTANCE OF RETABLO

Kahlo’s life wasn’t just focused on painting. She and Rivera were also passionate collectors of pre-Columbian artefacts and Mexican folk art.

Within their collection were 2,000 retablos – small paintings that flourished in popularity during the 19th and early 20th century in rural Mexico. Literally meaning ‘behind the altar’, retablos give thanks for a miraculous cure or divine intervention. Painted on tin, not by trained artists but by faithful believers, many feature the sick individual in bed, with the saint responsible for the healing looking down upon them from the heavens.

By their nature, retablos were not strictly realistic depictions of an event, but more an illustration of how the artist felt about what had taken place. Kahlo was not only a collector of retablos, but also an inspired exponent of this art form.

While in Detroit in 1932, where Rivera was working on murals for the Detroit Institute of Arts, Kahlo had a partial miscarriage, requiring her to have an abortion in the Henry Ford Hospital. Afterwards, she painted the traumatic incident. The work has many features of retablo; it was one of her first paintings on tin and, at only 12x15in, it is small.

We see Kahlo lying bleeding, naked and vulnerable on an enormous hospital bed. She holds artery-like ribbons with objects tied to the ends; the male foetus is the much-desired son she has lost, the snail represents the agonising slowness of the miscarriage and the anatomical model her damaged pelvis, making it impossible for her to have a child. Kahlo’s loneliness and helplessness are emphasised by the vast barren plain in the background.

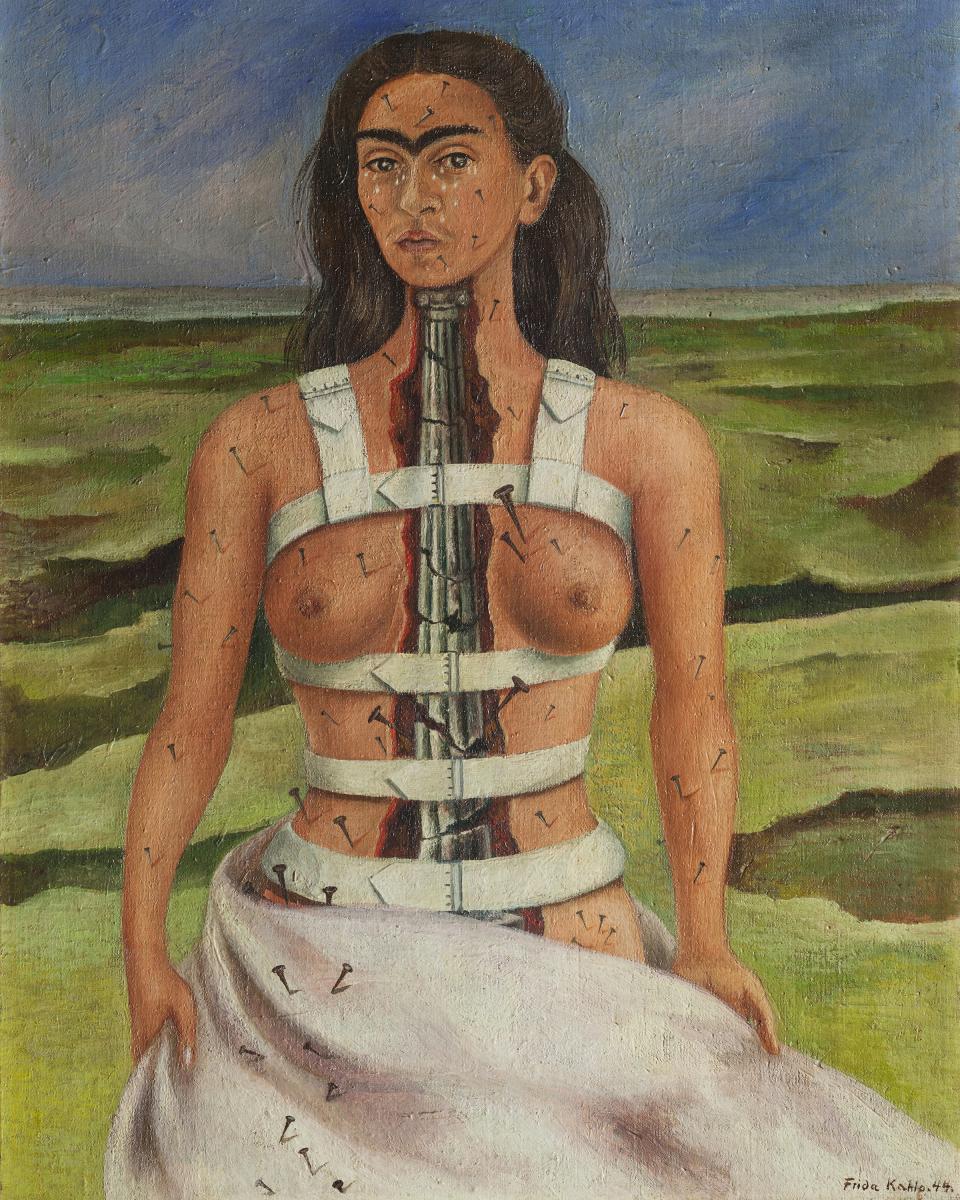

The Broken Column, 1944, oil on canvas on masonite

4. 'I PAINTED MY OWN REALITY'

Many of Kahlo’s paintings were autobiographical and, as such, offered a form of catharsis.

She said her paintings were like the photographs her father took for calendar illustrations, but instead of depicting outer reality, she painted the calendars in her head.

In the 1950s Rivera acknowledged his wife as, ‘the first woman in the history of art to treat, with absolute and uncompromising honesty… those general and specific themes which exclusively affect women’. These themes included miscarriage in Henry Ford Hospital, childbirth and maternal loss in My Birth, murder at the hands of a jealous macho lover in A Few Small Nips, and the pain of marital infidelity in Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair.

As well as physical pain, Kahlo endured emotional suffering through Rivera’s repeated affairs, including one with her own sister. But while her paintings express her suffering there is no self-pity, but instead an expression of intensity, resilience and strength.

The Broken Column was painted after Kahlo underwent spinal surgery and was no longer able to sit or stand, wearing orthopaedic corsets for support. The straps of the corset seem to stop her collapsing, holding her together and upright. An ionic column, broken in several places, takes the place of her damaged spine. The clefts in her flesh are reflected in the bleak landscape, only offering deep fissures and little hope. Her tears are reminiscent of Our Lady of Sorrows, a reference to retablo. But although Kahlo is physically broken, her gaze is one of defiant stoicism and inner strength.

One of Kahlo’s passions was for Mexican costume, such as this, one of her huipils (sleeveless tunics) and skirts, from before 1954, from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec

5. ELUSIVE RECOGNITION

Kahlo died in 1954 of a pulmonary embolism following a period of pneumonia, a week after her 47th birthday.

The headline of her obituary in The New York Times ran: ‘Frida Kahlo, Artist, Diego Rivera’s Wife’.

Like many women artists throughout history, Kahlo did not receive the recognition she deserved until many years after her death. Today she is acknowledged as one of the most important artists of the 20th century.

During the 1940s Kahlo did start to gain recognition in Mexico with commissions, patrons, a teaching post and a fellowship. In 1947 her painting The Two Fridas was acquired by the National Institute of Fine Arts in Mexico City for 4,000 pesos (approximately $1,000).

This was the highest price Kahlo was paid for a painting during her lifetime.

Almost 70 years later her painting Two Nudes in a Forest sold for $8m at auction.

Beyond a solo exhibition in New York in 1938 and a group exhibition the following year in Paris, she was little known outside Mexico. Indeed, it was not until a year before her death that Kahlo had her first solo exhibition in her native land. By then her health was so poor doctors forbade her to leave her bed for the opening; they hadn’t taken into account her indomitable spirit.

Kahlo sent her bed ahead and arrived by ambulance, carried in by stretcher, wearing her favourite colourful Mexican costume. She held court in bed, laughing and singing with her guests. The opening of the exhibition brought to life the subject she knew best: herself.

FIONA'S TOP TIPS

Visit

If travel allows visit the exhibition Viva la Frida! – Life and art of Frida Kahlo at the Drents Museum in Assen, the Netherlands, 8 October 2021–27 March 2022. It brings together, for the first time, the two most important Frida Kahlo collections in the world, along with personal objects that once belonged to the artist. The works in points 1-5 in this ‘Instant Expert’ appear in this show. For more see here.

View the paintings

Visit Kahlo’s atmospheric home, La Casa Azul in Mexico City, which is now a museum containing 10 of her paintings, photographs and personal items. The museum’s website has an excellent virtual tour.

Twenty-seven of Kahlo’s paintings can also be seen at Museo Dolores Olmedo; three at Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City; another three at MoMA, New York City, and, alas, only one painting in Europe, at Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris.

Recommended reading

Reissued in 2018, Hayden Herrera’s Frida (Bloomsbury Publishing) is an authoritative biography.

Kahlo’s own illustrated journal, written over the last 10 years of her life, The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait (Abrams), with facsimile pages in Spanish in the first half and translations in the second, enables yet more insight into the artist and her approach to her work.

Frida Kahlo in blue blouse © Throckmorton Fine Art, New York/Photo by Nickolas Muray © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives; Self-Portrait with Small Monkey © Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City © 2021 Banco de México, Ciudad de México/Reproduction authorised by INBAL, 2021; Henry Ford Hospital © Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City © 2021 Banco de México, Ciudad de México/Reproduction authorised by INBAL, 2021; The Broken Column © Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City © 2021 Banco de México, Ciudad de México/Reproduction authorised by INBAL, 2021; Huipil and skirt © Museo Frida Kahlo, Mexico City. Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera Archives. Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust.

About the Author

Fiona Rose

Fiona Rose has been lecturing on topics she feels passionately about for 11 years. She has a BA in social psychology and aims to include the human story behind the artistic endeavours of her subjects. Her Arts Society lectures include Frida Kahlo: A Life in Art, An Overview of the Life & Works of William Morris, In the Garden with William Morris: Flora as Art, Through the Keyhole: The Homes of William Morris and Uncompromising Genius: The Life & Works of Frank Lloyd Wright. Fiona is the founder and owner of a home interiors business. She is a former trustee of The William Morris Society, where she was chair of its communications committee.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition