This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on Fakes and Forgeries

Become an Instant Expert on Fakes and Forgeries

13 May 2020

Marc Allum has worked in the world of art and antiques for over 30 years, so it’s not surprising that he’s encountered a few fakes in his time. Here he uses his insider knowledge to give you five historic and practical pointers on the topic.

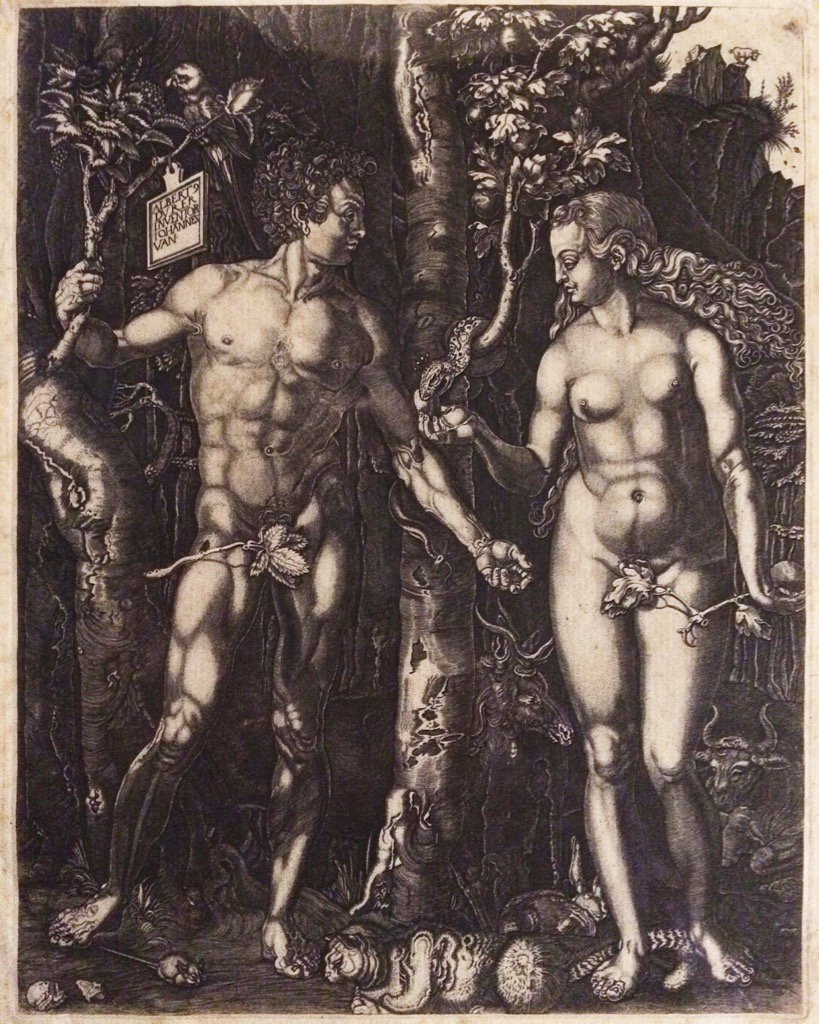

An Albrecht Dürer Adam and Eve original? No, a 'fake' by Johann Ledenspelder

An Albrecht Dürer Adam and Eve original? No, a 'fake' by Johann Ledenspelder

1. When is a fake not a fake?

The issue of fakes and forgeries is one that has fascinated me for decades. However, it’s a subject that opens a raft of moral and ethical issues and, as a collector who openly pursues certain types of fakes, it can be an area that tests one’s opinion of other’s principles. It’s also one that highlights a strangely sympathetic assessment of some audacious – and sometimes naive – historical fakers and forgers, while also decrying the blatant and morally corrupt business of pulling the wool over the eyes of a less well-formed, or inexperienced, customer or collector.

So, when is a fake not a fake? Frankly, it’s fairly easy for someone with my experience in the marketplace to weed out the most common types. In fact, the word ‘fake’ doesn’t define many of the objects for me, because I regard them as obvious reproductions.

The auction and retail world is awash with ‘copies’ of Franz Bergman cold-painted bronzes, Chinese ceramics, silver vesta cases, netsukes and antiquities. So whether you call an object a fake, a forgery, an imitation, a counterfeit, a copy or a reproduction, there are certain levels of deception that apply.

But if an object is made to deceive, then it’s a fake.

Some Edwardian facsimilies of diamonds

2. Historia Naturalis – authenticity and value

Perhaps it’s part of the human condition, but man has always sought to profit from fellow man. Whether honestly or dishonestly enacted, there are plenty of historical references to such acts and, as Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24-79) discusses in his work Historia naturalis (Natural History), man’s obsession with gemstones makes him particularly susceptible to fakes. Pliny’s contempt for this is obvious, as he remarks: ‘There is no other fraud practised, by which larger profits are made.'

The world of fakery largely relies on gullibility and greed and, from a personal point of view – in my business – it’s important to counter these issues early on in one’s career. Pliny may have been scathing of this gullibility, but let’s not forget that gems were mostly uncut in this period; all sorts of substitution would have easily been facilitated on the less informed.

Pliny was, in fact, an early debunker. His ‘encyclopaedia’ also illustrated the scratch test based on the hardness of diamonds. This is common knowledge to us, but gemstones, particularly diamonds, still carry a psychological baggage latterly distorted by the invention of the synthetic. Is it a fake, is it real or is it synthetic? What Pliny was illustrating was that the notion of authenticity and value were already ingrained in the human psyche.

A Ming copy of a bronze Shang Dynasty ‘jue’, or ritual wine vessel

3. Reverential fakes and reinvention

One of the main problems with fakes – and one that constantly creates a problem in my business – is man’s propensity for revisiting history and styles. For example, the Ming emperors valued the cultural output of earlier dynasties. It wasn’t unusual for them to have bronzes cast in the revered styles of the Shang Dynasty of 2,500 years earlier. These are now some 500 years old and are wonderful items in their own right – but are they fakes? Well no, but they are sometimes passed off as such.

Given the ‘heat’ of the oriental markets and the high prices paid in latter years for high-quality Imperial Chinese ceramics, the issue of reign marks has become folkloric, as auctioneers and scholars argue over later ‘reverential’ or ‘apocryphal’ marks on potentially valuable porcelain.

This has spawned a world of fakes, which makes provenance key too. Such complications are almost part of my daily routine. It often requires an offbeat or, dare I say it, obsessive ability to analyse and back-engineer objects, in effect putting yourself into the mind of the creator, to divine whether an item is right or wrong.

Being of a practical nature helps, but whether it’s an Edwardian copy of a Chippendale chair, a modern copy of an 18th-century fruitwood tea caddy, or a piece of ethnographic ‘airport art’ (tourist souvenirs purchased by unwary buyers), it’s important to realise that affirming provenance is far from straightforward.

Is it for real? A fake ‘Roman’ oil lamp, with a too good to be true portrait of Nero

4. The breadth of fakery

I love fakes. I love collecting them. Granted, some I’ve purchased solely to illustrate my lectures, but I’ve acquired many because they also denote attitudes in particular periods in history, and because they are sometimes misunderstood. Unlike banknote forgery, which is based purely on greed and profit, the creation – in the 18th century – of a Roman-style bronze or marble, subsequently sold to an unsuspecting Grand Tour tourist as the real thing, is intrinsically part of the history of fakes and forgeries.

Our museum storerooms are full of such items. I remember the wonderful 1990 exhibition at the British Museum: Fake? The Art of Deception. On display were some 600 items supposedly from the ancient to the more modern. I also recall some of the scepticism that raged about the museum ‘cleansing itself’ of its former mistakes; but that’s not fair.

What is fair is to say that in the course of making mistakes, be they in the 18th or 19th centuries, things have moved on both in knowledge and scientific terms. But the skill of the fakers has moved on too, meaning there is an inevitability that the experts and specialists who pronounce on such things can still be caught out.

5. Notorious fakers, Robin Hood, and fooling the establishment

Naturally, these ‘epoch sensitive’ fakes, that is, fakes and forgeries that were contextually accepted within the knowledge of the period, can be quite laughable in our terms. ‘Mermaids’ made of fish and monkey parts, for instance. But we also harbour a degree of admiration for good fakers who fool the establishment, or who appear to pass off fakes without financial gain being paramount. Some become folk heroes and whether what they do is morally right, that judgement becomes clouded by the stories that they create.

Illegal counterfeiting, be it currency or handbags, is a straightforward form of criminality; but I look at a woodblock I have at home by Johann Ledenspelder, a perfect 16th-century contemporary copy of Dürer's Adam and Eve (see top), and I can only marvel.

In the 20th century the burgeoning art market has become the victim of countless forgeries of the world’s great artists, with Picasso, Rothko, Pollock, Matisse and Klee being the tip of the forger’s iceberg. But I smile when I think of the Tom Keating ‘time bomb’ – the idea that an artist who couldn’t make a living out of his own work turned to forging the greats, such as Constable, only to be revered, after he was caught, as a Robin Hood character who captured the imagination of the public. No one knows how many of his paintings are still in private and public collections.

MARC'S TOP TIPS

Remember, if it seems too good to be true it probably is. The internet is rife with fakes, so when you are buying online beware the idea that a well-carved wooden netsuke from China is only £5. Yes, it is well carved, but unlikely to be old, even if it says it is.

Fakes can be a passport to owning items that you might otherwise be unable to afford, but the term ‘reproduction’ is probably more applicable. It’s important to exercise all of the diligence and caution that you would do with anything in life, be it a financial product or a second-hand car.

When buying at auction beware non-committal descriptions – always ask if you are not sure. The same applies in shops. Remember, too, that alterations don’t necessarily constitute fakery; they may be just old, honest repairs or modernisations. If in doubt get a second opinion, but remember, too, that not everyone is out to catch you out!

There are many books available on the subject; I’d recommend A Forger’s Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger by former art forger Shaun Greenhalgh. This salutary tale provides insight into the mind and heart of a garden shed faker, whose combination of artistic skills, creative provenances and complicit parents set a scene that rocked the art establishment.

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Marc Allum BA FSA is a fine art consultant, writer, lecturer and antiquarian. His career began in his early twenties in the London auction world and he has been a specialist on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow for 23 years. Although his experience denotes him as a generalist, his own personal interests and specialisms extend to antiquities and old cars, giving him a wide breadth of knowledge. He has written and contributed to many books on art and design. His lectures include The Anatomy of Antiques – The History of Collecting and Great Collectors, Fakes and Forgeries, Collecting the Grand Tour and Antiques Roadshow – 40 Years of Great Finds. He lives in Wiltshire.

Find out more about Marc’s work.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT EMAIL...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers, published every fortnight.

Show me another Instant Expert story.

About the Author

Marc Allum

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition