This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become An Instant Expert On The Banqueting House

Become An Instant Expert On The Banqueting House

18 Jan 2022

On a frosty January morning in 1649, Charles I stepped from the Banqueting House at Whitehall to his execution. The building, a masterpiece of revolutionary architecture, was central to the Stuart dynasty – a space that denoted power. Our expert, Siobhan Clarke, relates its story and the tale of why Parliament dared to kill a king

Charles I painted by court favourite, the artist Sir Anthony van Dyck

Charles I painted by court favourite, the artist Sir Anthony van Dyck

‘His Majesty received us in a great hall newly built for public spectacles, royally adorned with marvellous tapestries and gold’

A Venetian ambassador on a visit to the Banqueting House in 1625

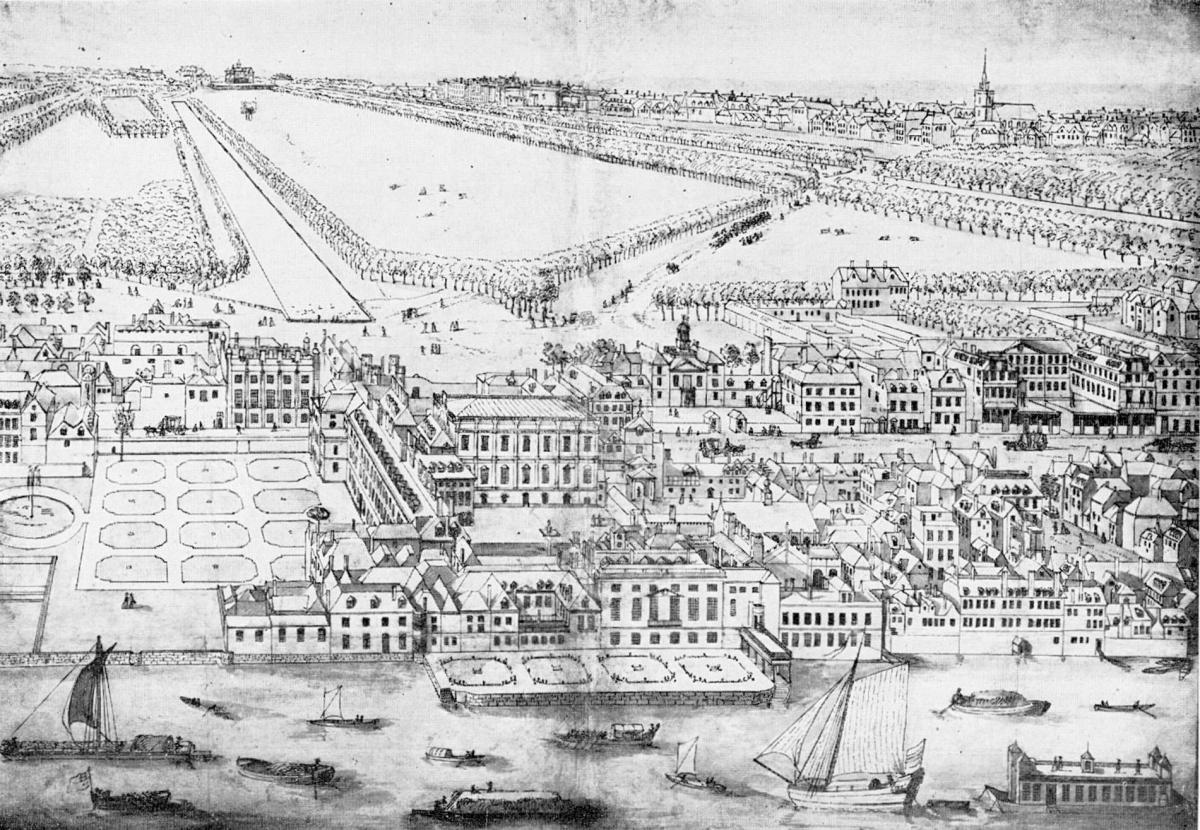

The last image of the Palace of Whitehall by the Dutch artist Leonard Knijff, with the Banqueting House shown in the centre, c.1695

The last image of the Palace of Whitehall by the Dutch artist Leonard Knijff, with the Banqueting House shown in the centre, c.1695

1. THE LOST PALACE

The Banqueting House is a remarkable survivor: the last part of Henry VIII’s lost Tudor Palace of Whitehall in London.

Henry had more than 50 great houses, but none were more important than his vast power base here. From 1530 it was the centre of government, combining the functions of present-day Buckingham Palace, Downing Street and all the government offices of Whitehall.

The original palace on the riverside was the royal residence. It had state rooms, privy apartments, chambers and courtyards. A pleasure complex was built on the other side with a tilt yard, tennis courts and spaces for games and amusements. All external surfaces were lavishly decorated. There was brickwork in red ochre, black and white timbering and the fanciful mural or sculptural decorative detail called grotesque (derived from the Italian grotteschi, in reference to decorated grottoes). It was so colourful that it would look to us like something out of Disneyland.

Inside the Privy Chamber a mural by the artist Hans Holbein portrayed the definitive Henry VIII – immense, chest thrust out and hand on dagger. It was a portrait that would make him our most recognisable English king and perfectly captured his majesty and menace. The painting expressed the power of the Tudors in a magnificent interior that echoed the gorgeous decoration of the palace itself.

Henry VIII died at Whitehall in January 1547. The building was later destroyed, in 1698, in an accidental fire. While the flames raged, Christopher Wren was ordered expressly by the Stuart king, William III, to focus his manpower on saving an architectural jewel at the heart of the complex – the 1622 Banqueting House.

Inside the great main hall of the Banqueting House, with Rubens' ceiling

Inside the great main hall of the Banqueting House, with Rubens' ceiling

2. REVOLUTIONARY ARCHITECTURE

In 1603, James VI and I united the crowns of Scotland and England, bringing two old enemies together in peace under Stuart kingship. This achievement would later be celebrated in the glorious Peter Paul Rubens ceiling in the Banqueting House.

James commissioned Inigo Jones, the first great English architect, to construct a new hall, but the term ‘banqueting’ is a misnomer. It was not intended for feasting but for propaganda entertainments to glorify the Stuart dynasty.

Jones had been to Italy and he designed what was considered revolutionary architecture, inspired by the Palladian style, based on the designs of Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–80). As the first classical design to be completed in London, in 1622, it must have stood out as extraordinary and modern amid the old, rambling Tudor buildings – a radical expression of the power of the Stuart line.

The main hall is a two-storey, double-cube room, in which the length of the room is twice its equal width and height; this is typically Palladian, where all proportions are mathematically related. The perfect balance, with large windows and soaring columns, is calculated in accordance with a Roman idea of perfection. Ionic half-columns embellish the whole room and fluted Corinthian pilasters run up to the ceiling.

At second-floor level one can see what is sometimes mistakenly referred to as a minstrels' gallery. In fact, while musicians may have played there, its true purpose was to admit an audience. The hall was to be used for grand receptions, formal entertainment and especially the performance of the Stuart court masque.

3. MESSAGES OF KINGSHIP

The dynamic partnership of Inigo Jones and playwright Ben Jonson produced a series of evermore elaborate and expensive masques at the Banqueting House. They can be described as a cross between a ball, a play and a fancy-dress party in which music, dance, song and recitation were all presented in exquisite costume.

For King James, and later for his son, Charles I, a masque was not merely entertainment: it demonstrated the Stuart concept of kingship, delivering messages about royal authority. Professional actors and members of the court took part in a script that always centred on praise for the monarch. A world of disorder was depicted, followed by audience participation as courtiers rose up and danced, creating harmony, in a ball that could continue all night.

The whole was accompanied by incredible illusionistic sets from Jones, with mechanical devices and ingenious lighting effects. Costumes could be revealing and participants were frequently drunk – it was not unusual for them to fall over during performances. Unsurprisingly, for the king’s enemies, all this was seen as evidence of the depravity of the court.

Such revelry in the Banqueting House all stopped in 1636, with the installation of Rubens’ ceiling paintings. The flaming torches and brilliant illumination of the masque could not continue once the masterpieces were in place. However, the messages of kingship had already been transferred to the canvas.

The Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland c.1632–4

The Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland c.1632–4

4. PAINTING A DYNASTY

King Charles I had an exceptional passion for art, bringing Anthony van Dyck to England and persuading Rubens, one of Europe’s most celebrated artists, to work on the ceiling paintings that would glorify himself and his father.

Painted in Antwerp, they were shipped over and put in place by 1636. Of all Rubens’ great works, the Banqueting House ceiling is the only one in the world to remain in its original setting.

In The Benefits of Good Government section of the ceiling paintings, King James points to the golden-clad Peace, who embraces Plenty. The Apotheosis shows us James going up to heaven, affirming the divine right of kings, answerable only to God. In The Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland, above, a child is said to represent Charles I, supported by the figures of England and Scotland, while Minerva holds the joined crowns of the two nations above his head.

Despite the power of such iconography, the Banqueting House soon became a physical expression of the divide between king and subjects, while the country descended into bloody civil war. From 1639 until his death, 10 years later, Charles fought the armies of his English and Scottish parliaments, who sought to curb his royal prerogative, his religious policies and the levying of taxes without parliamentary consent.

A higher proportion of the British male population died than in both world wars of the 20th century. Ultimately ‘Charles Stuart’ was held responsible for the terrible bloodshed. He was tried – in what was really the first trial for war crimes – and convicted of high treason by the Puritan English Parliament in January 1649.

The execution of King Charles I, unknown artist, c.1649

The execution of King Charles I, unknown artist, c.1649

5. TO KILL A KING

In every contemporary visual representation of this event the Banqueting House occupies a prominent position, for it was here that the king would die.

His enemies wanted a transparent and public execution, one that would take place outside the building that symbolised both the divine right of kings and – to the Puritans – the extravagance and decadence of the Stuart dynasty.

At 10 o'clock in the morning on 30 January a grim procession set off through the snowy air to Whitehall, the king surrounded by an escort of Roundhead soldiers. It was said that he had slept well and was up from 5am, asking for two shirts because of the bitter cold.

At the appointed hour Charles was led out through the galleries and, in an ultimate irony, passed beneath Rubens' magnificent ceiling, commissioned to glorify supreme monarchy – the last painting he ever saw. From here he stepped directly onto the scaffold from an upstairs window.

The 49-year-old king took off his cloak and laid his head upon the block. After a little pause, he stretched forth his hands and the executioner severed his head from his body. The rooftops were thronged with spectators and a great groan went up from the onlookers, as if they expected the very heavens to open. At one stroke of the axe, England had become a republic.

In May 1660, a joyous procession was to make its way to the same venue.

Charles II returned from exile to formally accept the crown in a glittering ceremony. It was the young king’s 30th birthday, and the monarchy was restored in the very place it had ended, the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace.

SIOBHAN'S TOP TIPS

See

The Banqueting House is temporarily closed, until further notice, but is open for private events and weddings. Updates can be found at Historic Royal Palaces

If you would like to visit another spectacular classical building by Inigo Jones, go to the Queen’s House at Greenwich, which was completed in 1636. More information can be found here: Royal Museums Greenwich

You can see a fine selection of works by Rubens in the National Gallery, London and The Apotheosis of James I and Other Studies: Multiple Sketch for the Banqueting House Ceiling, Whitehall c.1628–30 at Tate Britain

Good reads

Find out more about the parliamentarians who killed the king in Killers of the King: The Men Who Dared to Execute Charles I by Charles Spencer, 2015

I can also recommend Whitehall Palace: The Official Illustrated History by Simon Thurley, 2008, and Whitehall: The Street that Shaped a Nation by Colin Brown, 2010

My own book, The Tudors: The Crown, The Dynasty, The Golden Age (with art historian and Arts Society Accredited Lecturer, Linda Collins, 2019), covers James VI and I and the union of the crowns.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT EMAIL...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story

Images: Charles I from Wikimedia; Palace of Whitehall by Leonard Knijff © Alamy; Banqueting House © Historic Royal Palaces; The Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland © Bridgeman Images; The execution of King Charles I from Wikimedia.

About the Author

Siobhan Clarke

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Siobhan Clarke has worked for Historic Royal Palaces for 20 years delivering tours and lectures on the palaces of Hampton Court, Kensington, the Tower of London and the Banqueting House, Whitehall. She also lectures for the Smithsonian and has featured on BBC Radio 4's Woman's Hour and television's Secrets of Henry VIII's Palace. Her published work includes A Tudor Christmas and King and Collector: Henry VIII and the Art of Kingship. Her talks for The Arts Society include Majesty and menace – focusing on the Tower of London, The crown and the cradle, a talk on royal babies, and Royals at home: Kensington Palace – the home built by William and Mary, where the artist William Kent launched his dazzling career. Her talk on the Banqueting House is called The jewel in the lost crown and is her favourite lecture.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition