This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

BECOME AN INSTANT EXPERT ON THE AZTECS

BECOME AN INSTANT EXPERT ON THE AZTECS

14 Mar 2022

From where did they originate, how did they disappear – and why does the brilliant Aztec civilisation still loom so large in our collective memories? Art historian and Aztec expert Maria Chester reveals the answers

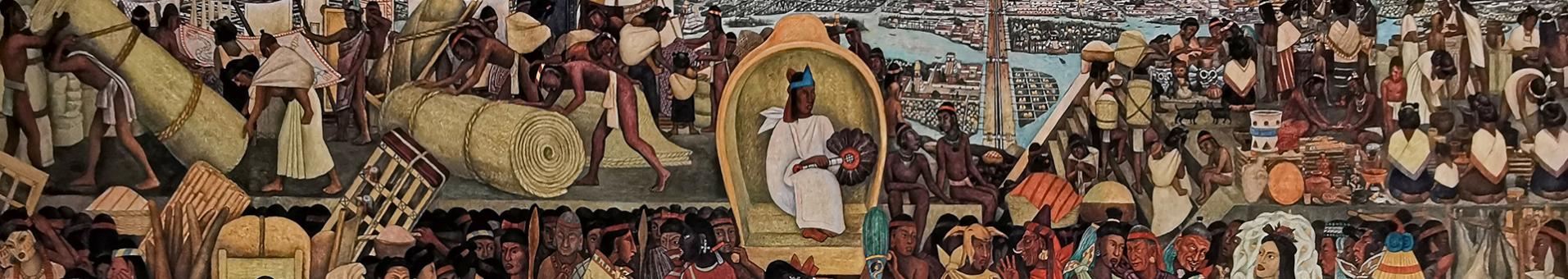

Aztec civilisation, as imagined by artist Diego Rivera, in his mural at the Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

Aztec civilisation, as imagined by artist Diego Rivera, in his mural at the Palacio Nacional, Mexico City

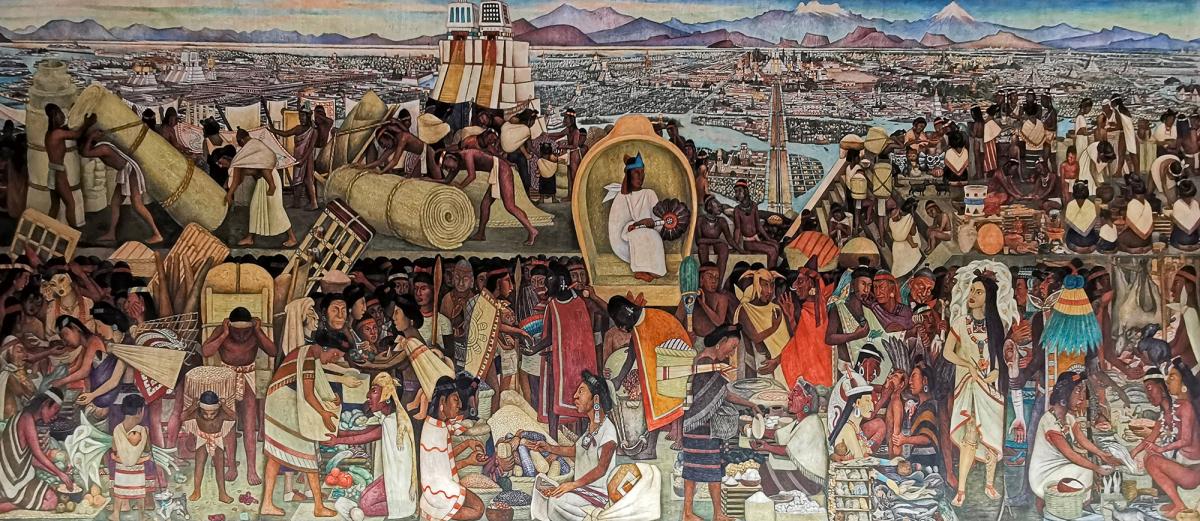

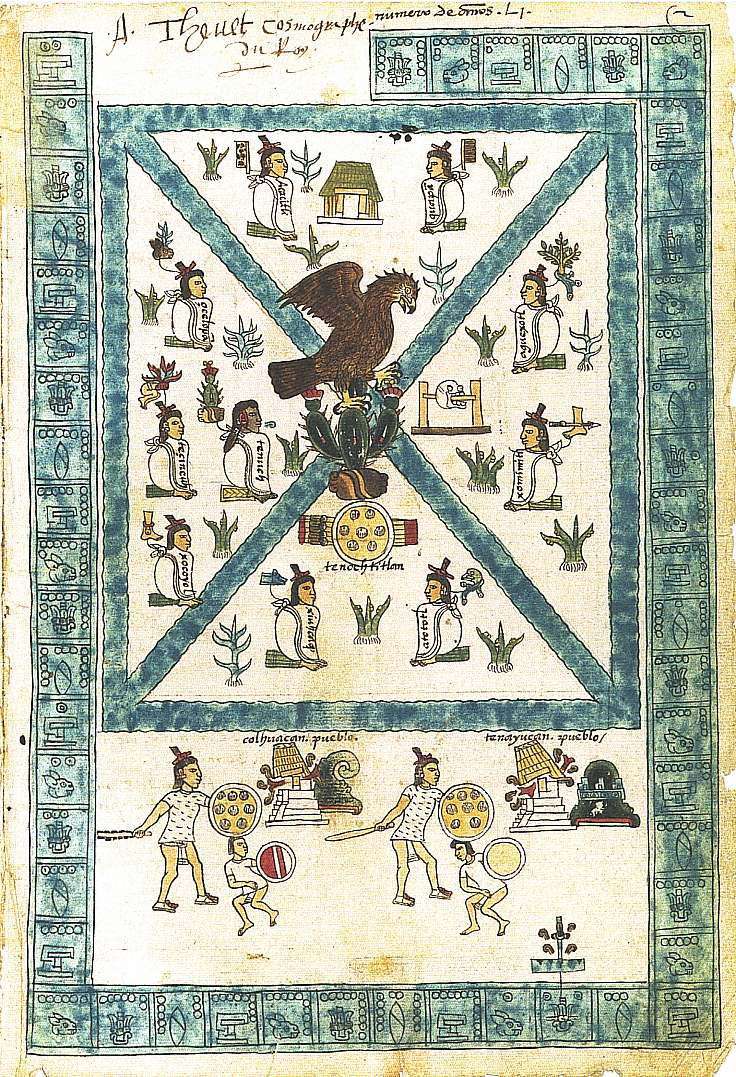

A 1704 map, a copy of an older image that was a representation of the Aztec migration from Aztlán to Chapultepec Hill, currently Mexico City

A 1704 map, a copy of an older image that was a representation of the Aztec migration from Aztlán to Chapultepec Hill, currently Mexico City

1. SOCIETY AND CUSTOMS

The Aztec (also once known as the Mexica or Tenochca) civilisation was highly developed socially, intellectually and artistically. By the 1500s their empire stretched from the Pacific to the Atlantic, creating a powerful confederation known as the ‘Triple Alliance’.

The Aztecs had migrated from Aztlán (‘Aztec’ means 'people from Aztlán’) in 1064. They settled in the Lake Texcoco area c.1250 and there they built their capital city, Tenochtitlán.

These people had two main social classes: the pilli and the macehualli.

The pilli ruled and were regarded as gods, with their warriors enjoying a glorified position in society.

The macehualli were farmers, traders, weavers or people who worked in the marketplace. Around 20% of the macehualli were dedicated to agriculture and food production. The Aztecs did not have beasts of burden, and no wheeled carts were used. All goods were transported by a porter or by small boats and canoes. The macehualli were trained from infancy to carry weights and, when adults, they could walk for 15 hours carrying 35kg on their backs.

Those of the macehualli who were travelling and trading goods were called pochteca – and it is known that the pochteca were also spies and informers. In addition, there were courtesans called auianime, trained to entertain the emperor and nobles. They were similar to the hetaera in Greece: professional courtesans who were not only beautiful, but highly educated and cultured. Prostitutes were also part of society, although not as well educated as the auianime. At the bottom of the social pyramid were the tlacotin: slaves that had been captured in battles or gleaned as payment for family debts.

Marriage was only allowed among members of the same class. The union was arranged after long negotiations between families and, to formalise, the mantle clothing of the man and woman were literally knotted together. A man could have only one legal wife and a family without children was considered cursed by the gods.

The man was the head of the family, but Aztec women had their own rights: they could own properties, run their own businesses, ask for advice in case of marital problems, and even request divorce in case of extreme cruelty. Their estate was divided equally and, after the divorce, both were free.

Adultery was punished with death.

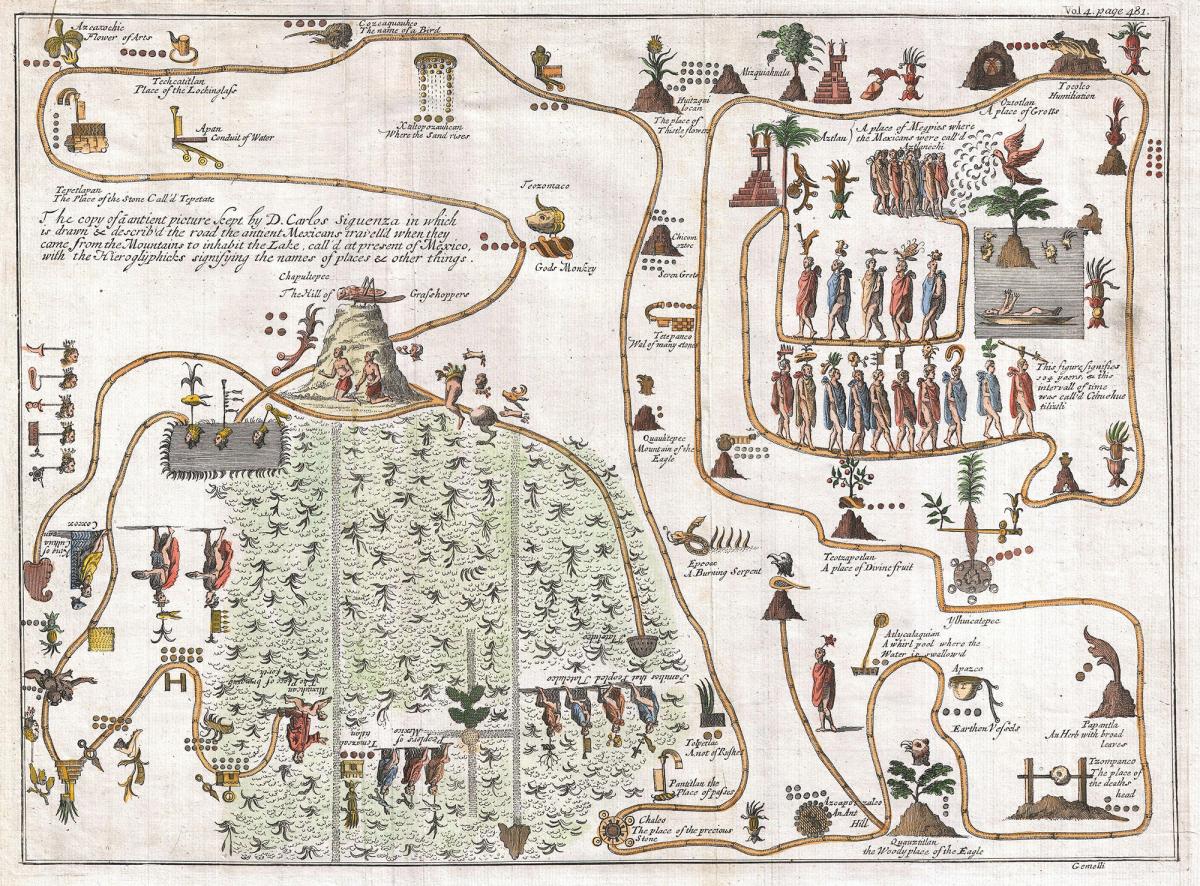

Goods, crops and trade: an illustration from the 16th-century Florentine Codex

Goods, crops and trade: an illustration from the 16th-century Florentine Codex

2. CACAO CURRENCY

The Aztec economy relied heavily on agriculture and farming.

Nobles owned all land. Commoners gained access to farmland by renting fields, and the Aztec farmers produced enough food to supply the entire empire.

They created a complex tributary system and, to keep the city markets provided with fresh vegetables, they used chinampas. These were a type of floating island orchard, on which the farmers grew produce. This floating ‘garden’ could literally be dragged by a canoe to the capital market and the farmer would cut only the vegetables required.

They also used the 'three sisters’ planting system, which allows the three main agricultural crops (maize, beans and squash or pumpkins) of the indigenous peoples of the Americas to grow symbiotically, to take advantage of the same spot of soil.

The pochteca (those travellers and traders) helped the economy. They travelled by foot for miles to sell and buy food, textiles, pots, jade, jaguar pelts, salt and vibrant quetzal bird feathers, among other goods. They had places to rest and eat and even latrines to use, sited at regular intervals. Their taxes supported the lavish lifestyles of the upper class, as well as the city state.

But at the heart of the Aztec economy was the marketplace.

Every town had one, where commoners would offer their goods and shoppers could barter. Tenochtitlán markets were located in the four corners of the city and were open 24 hours a day, every day, throughout the year.

Hernán Cortés – the Spanish conquistador – reported that the central market of Tlatelolco was visited by at least 60,000 people daily. The currency used was cacao beans and cotton blankets of specific quality and different sizes. You could buy, for instance, a rabbit for 30 cacao beans, or a turkey egg for three cacao beans.

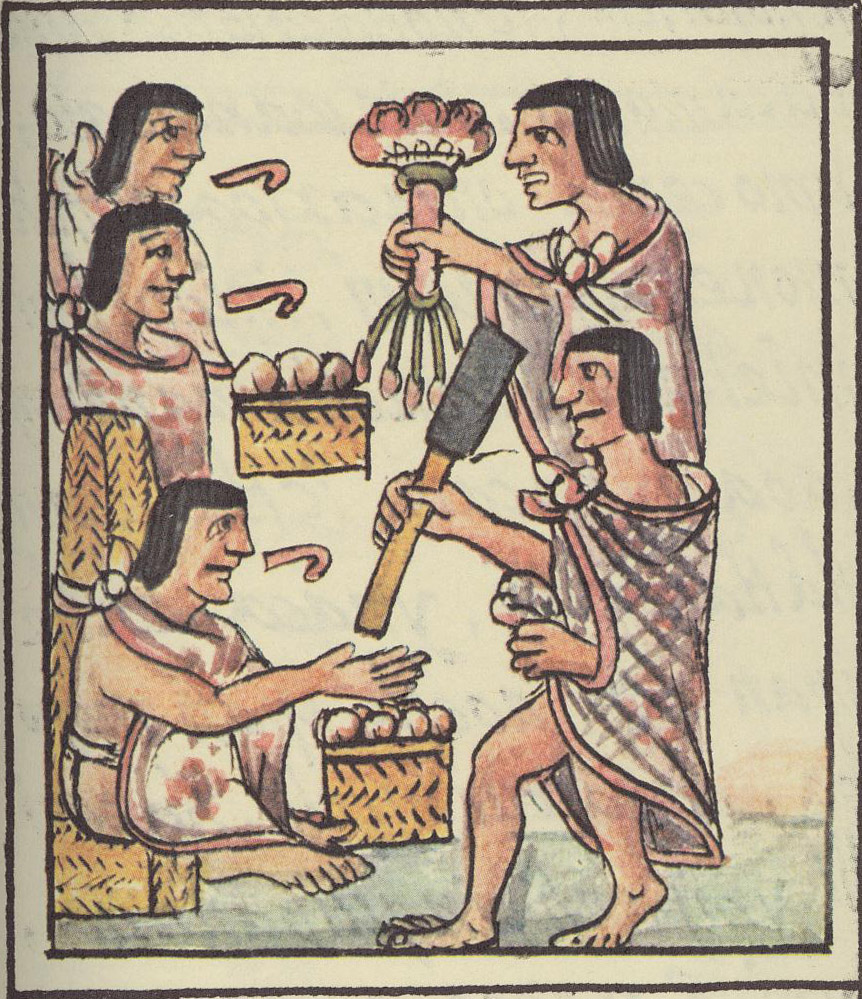

Music played an important part in Aztec society, as imagined here in the Florentine Codex

3. EDUCATION AND GOVERNANCE

The Aztecs were one of the few ancient civilisations that demanded mandatory education at home and in schools. Every child was educated, no matter his or her social status, whether noble, commoner or slave.

The emperor expected well-behaved people, so children were taught to be humble, obedient and hard-working. All children were taught a collection of sayings called the huehuetlatolli, which incorporated Aztec ideas and teachings. Education started at home, with parents, until the age of 14, and was supervised by the authorities of their calpulli (clan).

Every few years, these children were called to the temple and tested on how much they had learnt of this inherited cultural knowledge. Astronomy, rhetoric, poetry, history and religion were all taught at schools called calmecac ('house of the lineage').

The sons of nobles trained to be priests and the daughters priestesses. In the evening boys and girls gathered to relax and make and meet friends at the cuicacalli('house of song'). Music and poetry were highly regarded and there were musical presentations and poetry contests at most Aztec festivals.

The other school was the telpochcalli ('house of youth'), where boys undertook military training and learning by heart, as reading and writing weren’t taught there. The patron god of the telpochcalli was Tezcatlipoca, the god of war. The tlamatini('wise man') was in charge of the writing and maintenance of the codices.

When it came to governance and Aztec leadership, the huey tlatoani (the supreme leader) was at the top, helped by the advice of the city council (a sort of Roman senate), which received instructions and requests from the calpulli.

The founding of Tenochtitlán, as illustrated in the mid-16th-century Codex Mendoza

The founding of Tenochtitlán, as illustrated in the mid-16th-century Codex Mendoza

4. TENOCHTITLÁN – THE VENICE OF THE AMERICAS

According to their codices, the Aztecs founded their island capital, Tenochtitlán, on 13 April 1325.

At its height it had more than 200,000 inhabitants and was the most densely populated city ever to exist in Mesoamerica. The entire Aztec empire had more than 15 million people.

The city was laid out in a grid pattern, with canals (which facilitated transport and communications) crisscrossing it; it was also connected to the shores of Lake Texcoco by three elevated causeways. Cortés reported that the causeways were ‘as wide as the width of eight horses’. They included removable bridges that allowed boats to pass. A stone aqueduct brought fresh water from springs located at Chapultepec Hill. The lake was kept clean and was an important source of food.

At the heart of the city was the Great Pyramid (50m high) with twin temples: a blue one dedicated to the god of rain and a red one to the god of war (Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli, respectively). The whole complex was enclosed by a wall called coatepantli ('wall of serpents').

The two-storey royal palace of Moctezuma, with its gardens and courtyards, was next to the temple. The walls were decorated and, again, according to the Spanish, the palace even had a zoo. The other (some 400) palaces, called Axayacatl, were for the nobility. The remaining population lived in spacious four-room houses made of adobe, all with access to the canals. And, as the Aztecs strongly believed in personal cleanliness, each had a steam house, with their temazcal ('house of heat') located next to the home.

The conquest of Mexico by conquistador Hernán Cortés, by an unknown 16th-century artist

5. THE BEGINNING OF THE END

In April 1519 Cortés landed on the Mexican coast and founded the town of Veracruz. He had with him 508 soldiers, 100 sailors, 14 small cannons, horses and mastiff dogs trained to kill.

As a welcoming gift from the lord of Potonchan he was given a noblewoman called Malinalli Tenepal, later known as La Malinche, who became his lover and translator.

When Cortés arrived, the Tlaxcaltecs and the Totonacs were under the thumb of the Emperor Moctezuma. But Cortés immediately understood that the so-called Aztec empire was anything but unified. He studied the Triple Alliance (formed by Tenochtitlán, Tlacopan, and Texcoco since 1428) with a view to dismantling it.

A clever strategist and an astute politician, he then sent ambassadors with presents to impress Emperor Moctezuma, and was invited to Tenochtitlán.

Cortés entered the city on 8 November 1519, with his horsemen in cuirasses (armour) with iron lances behind them, foot soldiers with swords, crossbowmen and 20,000 men from Tlaxcala. He was greeted with flower petals, invited to be a guest in one of the palaces and was called 'teteo' (a god). He was given tobacco to smoke in a pipe and hot, spicy chocolate, served in a golden cup.

During this time Cortés came to admire this unique civilisation; so much so, he decided to conquer then colonise it.

He sent letters to Charles V, the Spanish king, with details of the sacrifices performed by the Aztecs, without any intention of coming to understand their religion and the beliefs behind such sacrifices. (The Aztecs believed that, for the sun to rise each day, the gods should be appeased with human blood and hearts.)

Moctezuma was imprisoned and kept as the Spaniards’ hostage in his own palace. He died while in their custody. After this magnicide, the Spaniards invited the whole nobility to a ceremony in which they were all assassinated. The Spaniards were in turn attacked by the people, and retreated with all the gold they could carry. Cortés returned to place Tenochtitlán under a siege that lasted 75 days. Despite the fierce defence of the city by Cuauhtémoc (the nephew of Moctezuma, whose name meant ‘the falling eagle’), surrender became inevitable on 13 August 1521. Tenochtitlán was destroyed; its people were starving.

The Triple Alliance capitulated on 21 August 1521, bringing an end to Mesoamerica’s last great civilisation. The Aztec empire disappeared and the Spaniards built Mexico City on top of the ruins of Tenochtitlán.

Charles V gave Cortés the title of first Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca, in recognition of ‘his achievements’.

The splendour of the Aztec civilisation was gone forever.

MARIA'S TOP TIPS

Visit

- Room 27 at The British Museum has treasures of the Aztecs and other cultures of Mexico

- If you travel to Mexico, a visit to the National Museum of Anthropology is a must; it has a vast collection of Aztec artefacts

- The Museo del Templo Mayor in Mexico is also full of Aztec sculptures found in recent excavations by Professor Eduardo Matos Moctezuma

Good reads

- Aztecs, by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Felipe Solís Olgulín, published by Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2002

- Aztec, the historical novel by Gary Jennings, published in 1980 by Atheneum

About the Author

Maria Chester

Buenos Aires-born Maria is an art historian specialising in the ancient civilisations of the Americas. She has been an Arts Society Accredited Lecturer since 2018. Another of her passions is rock art, for which she has developed a course on Palaeolithic-Ice Age art. Among her many lectures and Study Day topics for The Arts Society are The Aztec: an introduction to the most complex urban culture of the Americas; The Maya Children of the Corn; The Inca: Children of the Sun; The dawn of art: art of the Ice Age and A brief history of drawing, from cave art to Banksy.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition