This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the art of Mary Newcomb

Become an Instant Expert on the art of Mary Newcomb

12 Feb 2021

A self-taught painter, by the time of her death in 2008 Mary Newcomb’s work was celebrated for its exquisite rendering of nature and wildlife. As a new exhibition on her work prepares to open, Arts Society Lecturer Christopher Andreae shares the core details on her life and art

Mary Newcomb in her workroom © Estate of the artist; all other images © Mary Newcomb Estate.

Kew, The Delicate Jungle

Kew, The Delicate Jungle

‘I wanted … to remind ourselves that – in our haste – in this century – we may not give time to pause and look – and may pass on our way unheeding’

Mary Newcomb, writing on New Year’s Day, 1986

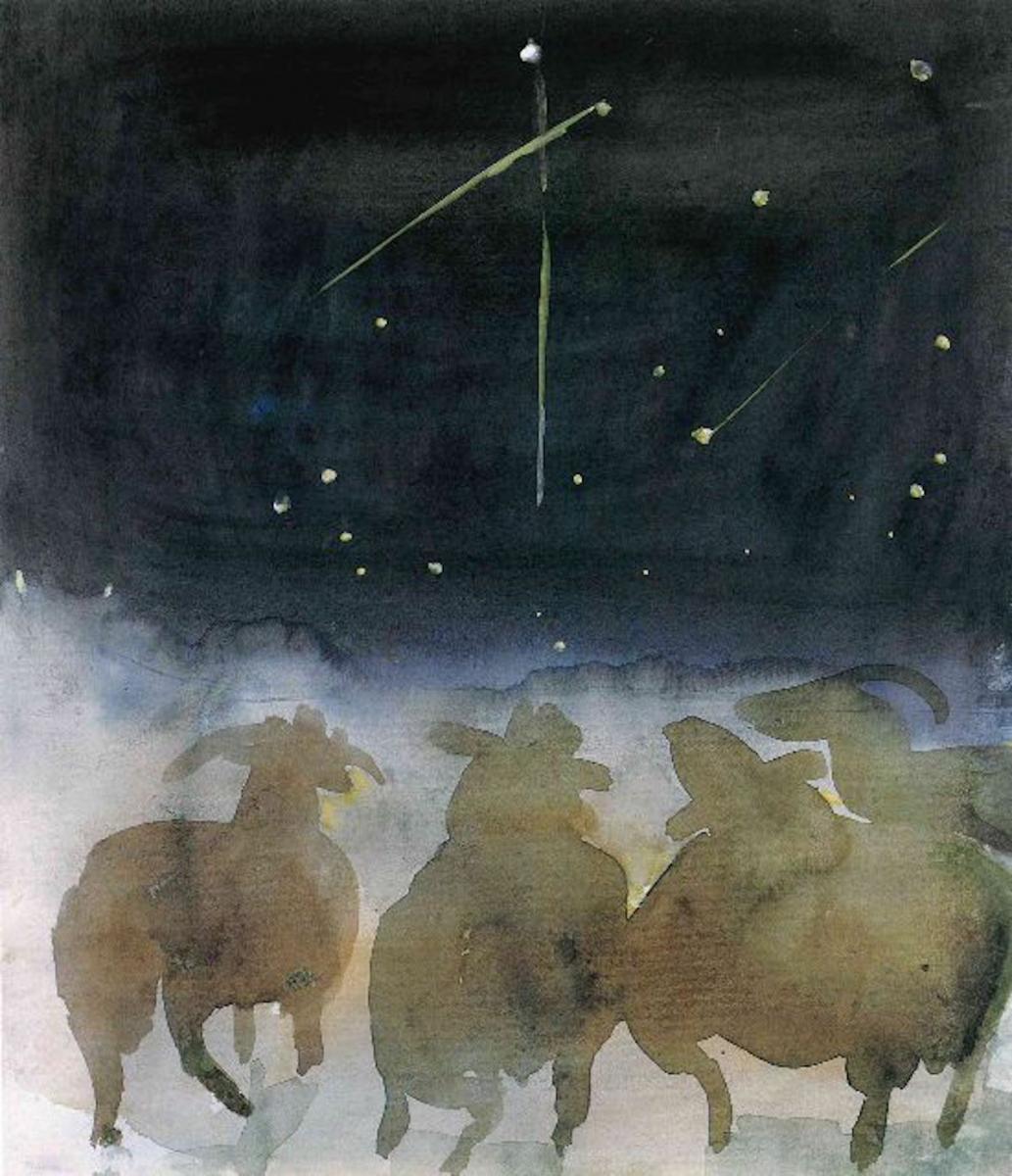

Ewes Watching Shooting Stars

Ewes Watching Shooting Stars

1. A NATURAL TALENT

Mary Newcomb was born in 1922 in Harrow-on-the-Hill. It was not until post-World War II and as late as 1950 that she found it possible to pursue her vocation as a serious artist. She had taken a degree in natural sciences in 1943 and went on to teach science and maths in Bath. But by 1950 she was married to Godfrey Newcomb, a potter and farmer, had had two daughters, was living in Norfolk and was decorating her husband’s pottery.

Becoming an artist in her own right would have looked unlikely to anyone else. But her love of drawing went back to Newcomb’s childhood. She remembered a teacher telling her that her sketch of blackberries was good. ‘Yes, I know,’ she said quietly, and skipped home.

As the highly observant artist and naturalist she became in maturity, she always carried scraps of paper with her, ready to draw on. Those drawings were an aide-memoire, possibly later transformed into large paintings (she liked to give those drawings to appreciative friends). Her London dealer, Andras Kalman, meanwhile, was responding to demand for her work, asking the artist for more and more drawings and paintings.

Mary Newcomb in her workroom

Mary Newcomb in her workroom

2. WAY OF WORKING

Newcomb’s paintings were developed according to her own techniques and procedures as an ‘untaught’ artist, to borrow a phrase she used in reference to her work.

Her studio contained a number of canvases that she prepared in advance. In order to avoid bare and clinically white surfaces she covered these with atmospheric colours. These abstract, and often rather beautiful, hues were composed of the remains of oil paints left on her palette, and would eventually act like backgrounds to final paintings.

In her diary she explained how she worked: ‘I paint with the canvas against a wall … I tilt it forward at the base for stability. This seems to give me a foothold actually within the canvas about ¾ down, a little platform of my own, for myself on the stage … so that I have a measured amount of space all round me as an actor might have and feel. This gives me the ability to reach out to left and right and behind my shoulders and I am part of the action, in the trees, on the water, in the air, with the figures and living in there, in a landscape, totally involved and living in there.’

3. SOPHISTICATION AND NAIVETY

If Newcomb’s drawings are by their very nature quick and (for her) easy – birds flying up suddenly, or insects settling on a flower head – her paintings are ‘wonderfully difficult’. She relished the difficulty, the problems they presented. She frequently mentions the struggles that nobody else would understand. For example: ‘Trying to control the blues, depth, texture, overall balance of Girl with butterfly brooch gathering limpets.’

Any notion that this was the thinking of a primitive or naive artist, an Alfred Wallis or even a Henri Rousseau, is unconvincing. Newcomb knew exactly and self-critically what her aims were and if they succeeded or failed. On a visit to Paris she afterwards mentioned disappointment at having missed seeing any primitive art – as if it were something she wanted to learn more about.

There seems to have been something childlike – simple and directed – about her art and life. Her diary does not hide this side of her. One day she watched a lady (comically) ‘dropping bread on a swan’. The same day she noted: ‘I hold green grass dear,’ and: ‘Today I moved the wood anemone lest it be squashed.’ She enjoyed the expressiveness of colour for its own sake, swearing she will exaggerate the red pigment in a painting she is working on, to ‘outclass’ the geese in the farmyard that are being particularly ‘raucous’. She humorously notes as a potential theme for a painting something she calls ‘half men’. In one work these share the stage with convolvulus flowers and visiting bees – ‘half’ because the men are half hidden in the dips of the switchback road along which they are walking. And there is a stiff lady ‘softened by wild flowers’. And ‘a man hurtling downhill on his bicycle, just like a squirrel with his elbows sticking out. And men and women carrying bunches of flowers too big to carry on their bikes’ – and on it goes, seemingly always with laughter round the corner.

Insects on Hogweed, with the artist’s pencilled notes

Insects on Hogweed, with the artist’s pencilled notes

4. CORE INFLUENCES

Newcomb believed that all artists, including her, had to invent their own language. Each language in turn modifies the vision of others. To say that she herself was not part of ‘the art world’ is to write her off impossibly, though it is true that she did follow her own convictions with considerable originality. Although doing so, there were figures who had a key influence on Newcomb’s art, one being Dr Eric Ennion (1900-81), who she met when she was still working as a schoolteacher.

Ennion was a bird artist, author and warden at the Field Studies Council's Flatford Mill Field Centre. Newcomb was fascinated with the idea of drawing and painting nature outdoors, as Ennion did, but as with all her influences, she was later to introduce an element of idiosyncrasy and humour into her art.

Other more widely known artists with whom she sensed fraternity included Paul Klee, Pierre Bonnard, Giorgio Morandi, Milton Avery and Ben Shahn. But this list would be incomplete if it excluded ancient and often anonymous artists whose work and approach to art she had also absorbed. The point is that Mary Newcomb was an avid reader – and this included poetry no less than art. Her diary includes mentions of Thomas Hardy, John Clare, Robert Frost and more.

The Lady with a Bunch of Sweet Williams

The Lady with a Bunch of Sweet Williams

5. TAKING HER TIME

Mary’s career as a naturalist artist coincided with a post-war move by naturalists away from the study of specimens and towards field studies. ‘I crossed a bee flight path today,’ she mentions on 8 June 1986 in her one and only diary. This diary is not illustrated, but it is peppered with close-up observations and moments, many of which find their way sooner or later into drawings and paintings.

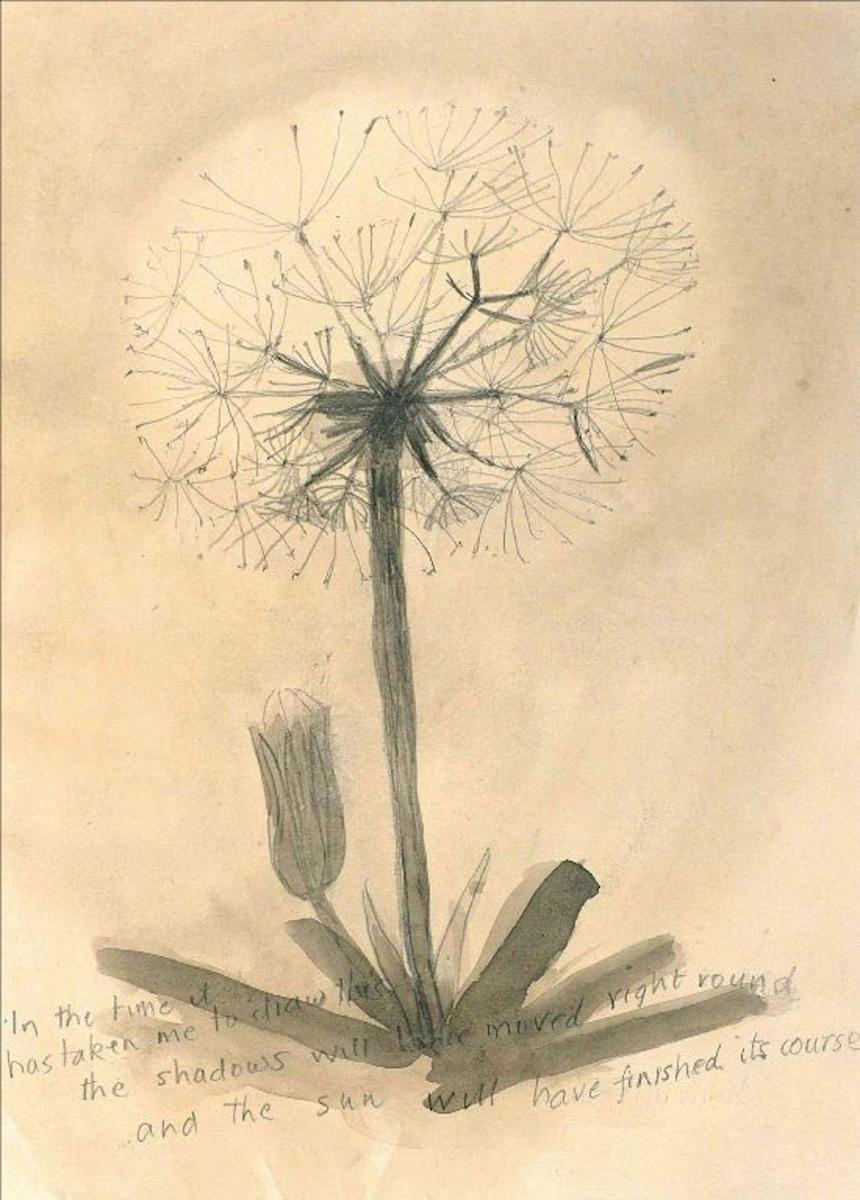

Time is inevitably part of this rapport with nature. She did not give the title Dandelion to the drawing of a seed clock shown here (probably because it is botanically more like a ‘goat’s-beard'), but she wrote a caption actually on top of it that touches on the time element in her thinking. Her slightly ironic words read: ‘In the time it has taken me to draw this the shadows will have moved right round and the sun will have finished its course.’

And there are other ways in which she conveys the movement of her chosen subjects. One is the employment of cartoon composition in a sequential narrative – of progressive takes. In this manner she depicts a tern feeding its young; the ‘passage of the black dog’ (the identical dog appearing repeatedly as it walks over a bridge); a weasel moving its young 'from loose straw to baled straw and back again’; and then ‘5 phases in the movement of a flock of goldfinches’.

The Lady with a Bunch of Sweet Williams

The Lady with a Bunch of Sweet Williams

6. ASSESSING HER WORK

There is a quote gleaned from a note Newcomb wrote to herself that reviews her sense of her work as an artist, stating purpose as well as modesty. ‘These are not great paintings. I am just trying to say something about peace and space round oneself.’ And then she adds: ‘Time passing now.’

Although not naturalistic, Newcomb's paintings powerfully evoke the different atmospheres and personalities within her surroundings. The simplicity of her style gives her art immediacy. Though her work is lyrical, it is also thoughtful and unusual, offering unexpected views of everyday, rural moments. This trait is further developed in the titles she gave her work: Cows Affronted by Land Drains, for example, or These Sheep Find it Necessary to Cross the Bridge.

For a large part of her life, Newcomb’s paintings remained outside the world of the art establishment. It was not until 1997 that the Tate acquired one of her pieces, People Walking Amongst Small Sandhills, for its collection. Regardless of her rise in recognition, Newcomb’s style remained constant and her unique view on the world is immediately recognisable.

CHRISTOPHER'S TOP TIPS

Recommended reads

- The most recent book on Newcomb is Mary Newcomb: Drawing from Observation by Tessa Newcomb, the artist’s daughter, with an introduction by William Packer. It is published by Lund Humphries (2018) in association with the Crane Kalman Gallery. It reproduces many of her sketches alongside her finished paintings and short diary extracts.

- My earlier book, Mary Newcomb, can be found (now only second-hand) at Bookfinder.

See

A major exhibition of Mary Newcomb works – Mary Newcomb: Nature’s Canvas is at Compton Verney Art Gallery from 2 April–18 July 2021.The Crane Kalman Gallery in London represents Newcomb’s work.

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Christopher Andreae graduated with an MA in fine art from Cambridge University and is an art critic, lecturer and artist. He is the author of five publications, including works on Winifred Nicholson and Mary Fedden, as well as Mary Newcomb. Among his lectures for The Arts Society are Mary Newcomb – a necessary connection with the earth, Mary Fedden – enigmas and variations and Joan Eardley: a Scottish artist’s alternative view.

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

About the Author

Christopher Andreae

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition