This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the art of Georgia O'Keeffe

Become an Instant Expert on the art of Georgia O'Keeffe

26 May 2021

Georgia O’Keeffe was one of the most significant artists of the 20th century, combining the figurative and abstract to dazzling effect. This year there are three major exhibitions of her work on show in Europe. Our expert, Dr Deborah Jenner, explores the story behind her art

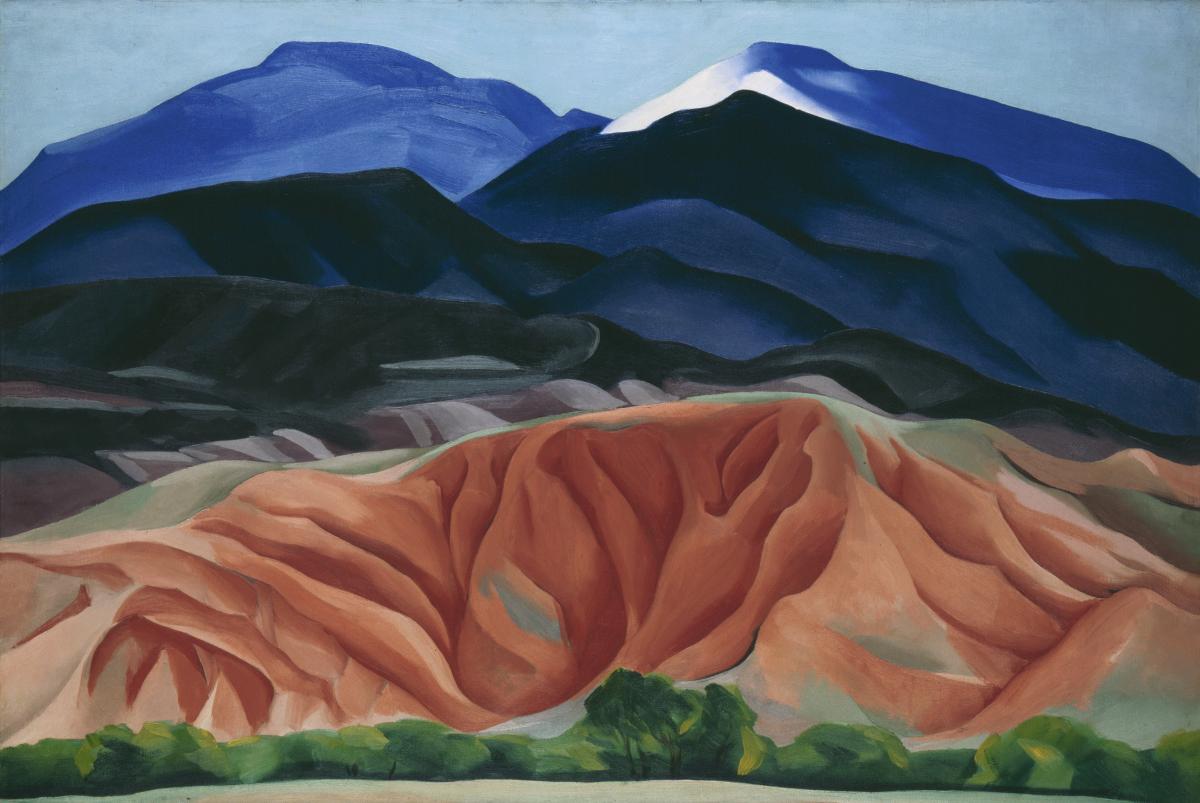

Georgia O’Keeffe's Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico/Out Back of Marie’s II, 1930

‘Nothing is less real than realism… It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis that we get at the real meaning of things’

Georgia O’Keeffe, 1922

From the Lake No.1, 1924

1. NATURAL FORCES INSPIRED ABSTRACT DESIGNS

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in 1887 and grew up on a Wisconsin dairy farm where excitement came from blizzards and tornadoes. She loved to watch them looming over the prairie’s horizon.

While an arts teacher in Texas, she found innovative ways to depict the western skies which were, as she exclaimed, ‘just blazing – and grey-blue clouds were rioting all through the hotness of it’.

Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer, started showing her abstract work at his 291 gallery from 1916. When he convinced O'Keeffe to move to New York in 1918, she continued weather-watching from his family country home. With From the Lake No.1, shown here, O’Keeffe reveals the sublime beauty in apparently random patterns of lapping water, rainclouds and lightning. Her shapes resonate to weave the very tissue of the event.

O’Keeffe’s abstract designs are most often inspired by natural forces – a testimony to her deep engagement with the land. She was following the transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson’s directives to regard nature as an activity instead of substance. Inspired by his ‘transparent eyeball’, she portrayed all viewpoints at once. Her composition could work any way round. Likewise, she avoided any directional light source by creating painterly equivalents for both fill-in flash and backlit photography.

Her clashing colours can be compared with Jazz Age syncopation: electric blues, acid greens and sizzling winey-reds transform matter into energy and back again.

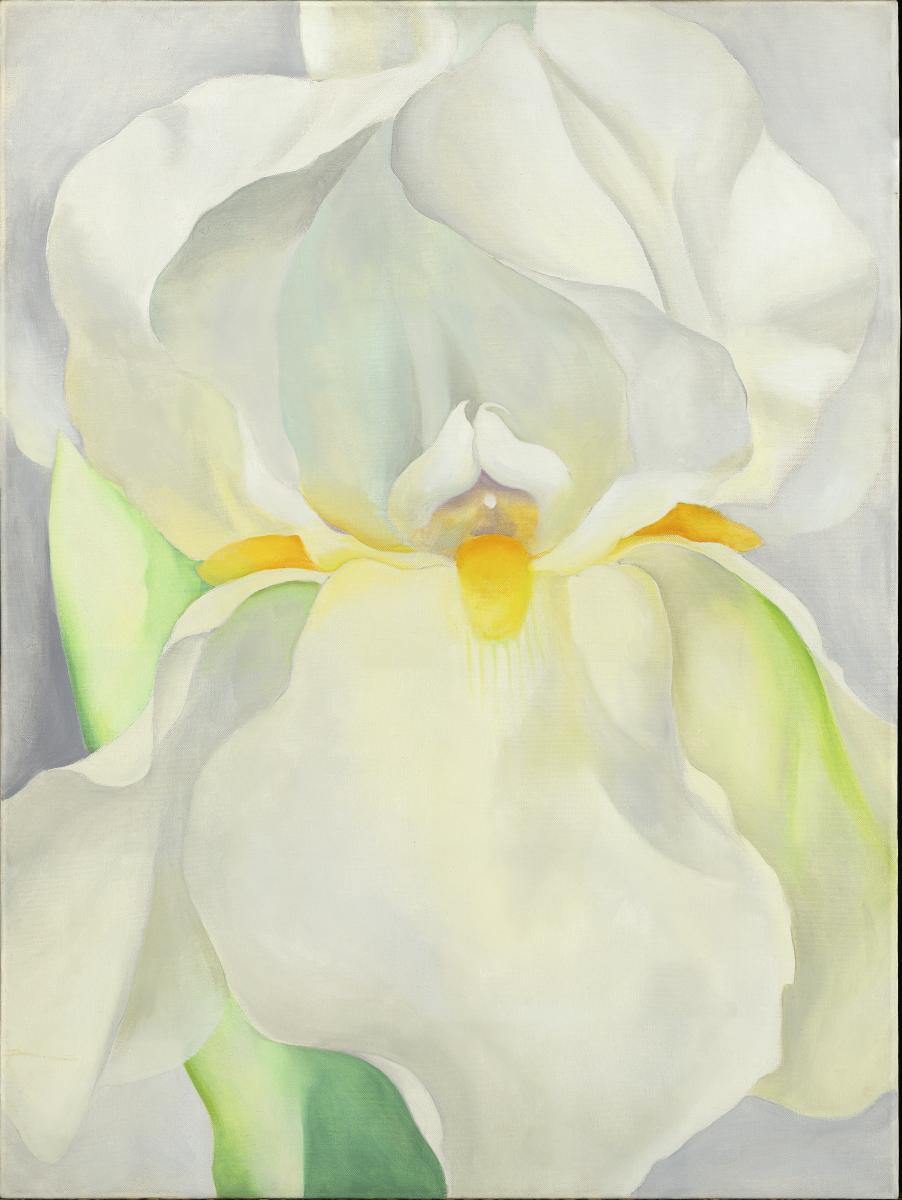

White Iris No.7, 1924

2. RELISHING SENSUAL DELIGHTS

By 1919 O’Keeffe and Stieglitz were a couple. O’Keeffe’s ‘self-portrait’ the year of her marriage (1924) was her first immense petunia. Its centre dove deep into a golden pool that resembles the pupil of an eye, which in turn seems to stare at us knowingly.

With White Iris No.7, pictured here, the true subject is pure light and whiteness. Yet the white is painted with a rainbow of opalescent nuances in gently graded tonalities. The flower’s iridescent texture is like that of O’Keeffe’s Irish-origins skin. The bloom’s erotic, soft petals part to reveal deep, cavernous inner chambers.

O’Keeffe’s flowers were neither those of a botanist nor a decorator. Although she always carefully elaborated details of the stamen, pistil and buds, most showed little stem or foliage. She did not uphold the naturalistic accuracy of the still-life tradition. Some petals were left out to suggest rather than represent reality. Her style varied little. Smoothed brushwork let the flowers’ forms themselves pulsate with life.

She selected species with lush, enfolding petals that had clean edges, avoiding Impressionist-like zinnia. All were pressed up against the picture plane. Their seedpods hypnotised the viewer. She painted blossoms so enlarged that they became hallucinogenic, erupting from the canvas.

O’Keeffe justified that she was letting the viewer experience the blossom from a bumblebee’s perspective, to drink in the nectar. Tantalising further, her floral canvases often played with discord: closed-rooted white lilies and wide-open purple petunias; lavenders out of key with deep reds.

She would paint some 200 flower works over her long career, but kept most in her private collection. Until she published One Hundred Flowers in 1987, few were well known.

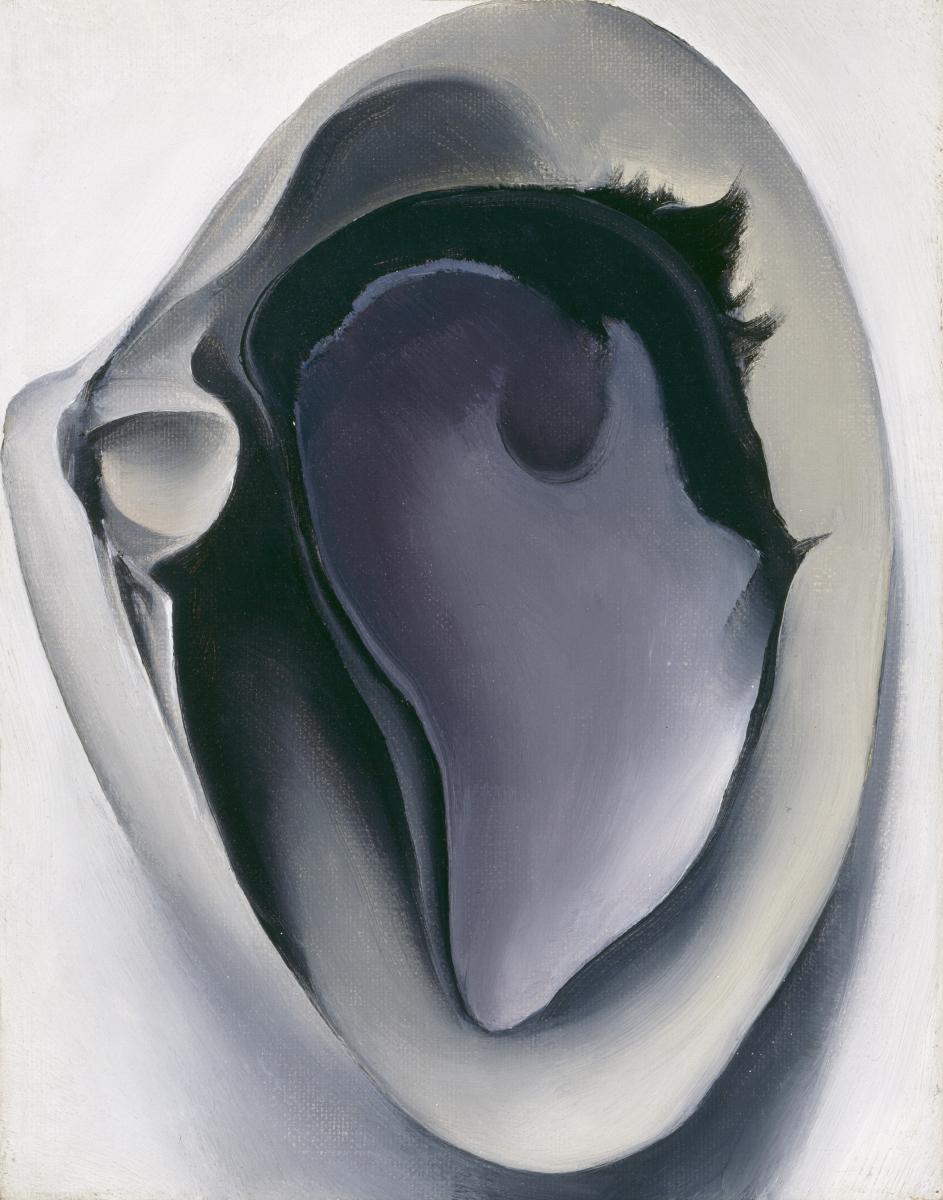

Clam and Mussel, 1926

3. UNBOUND BY CONVENTION

Stieglitz was against O’Keeffe’s maternal desires and declared: ‘You’ll never be able to paint if you have a child around.’ Yet they stayed together as co-workers who believed in the same things.

Stieglitz’s darkroom and O’Keeffe’s blank canvases became a sort of ‘second womb’. Their creative worlds intertwined. She admitted to the intense sexual chemistry that his many nude portraits of her arose – a photographer’s model has actually the male role, since the camera is penetrated by light. Stieglitz nicknamed her his ‘white light’. O’Keeffe’s own visual language eloquently expressed sensations otherwise too intimate to be shared.

Her paintings celebrate the non-dualistic spirit of yin and yang. Having studied composition with Arthur Dow at Columbia University, she applied his technique of Notan (Japanese for dark/light) that organises large, flat, tonal zones into one bold, interlocking graphic design which, in turn, lets the light circulate. This freed her from European art’s linear perspective, heavy shadows and accidental colour. She kept her brushwork very discrete. Her impersonal Precisionist style – like that of Straight Photography – preferred a frontal view. Her motifs also fit perfectly on the canvas, so avoiding awkward corners.

Her subtle wit let her still lifes, such as Clam and Mussel shown here, evolve into actual ‘portraits’. Displayed vertically, they give off an anthropologic air. Shellfish as sentient beings redefine the frontiers of what is an individual.

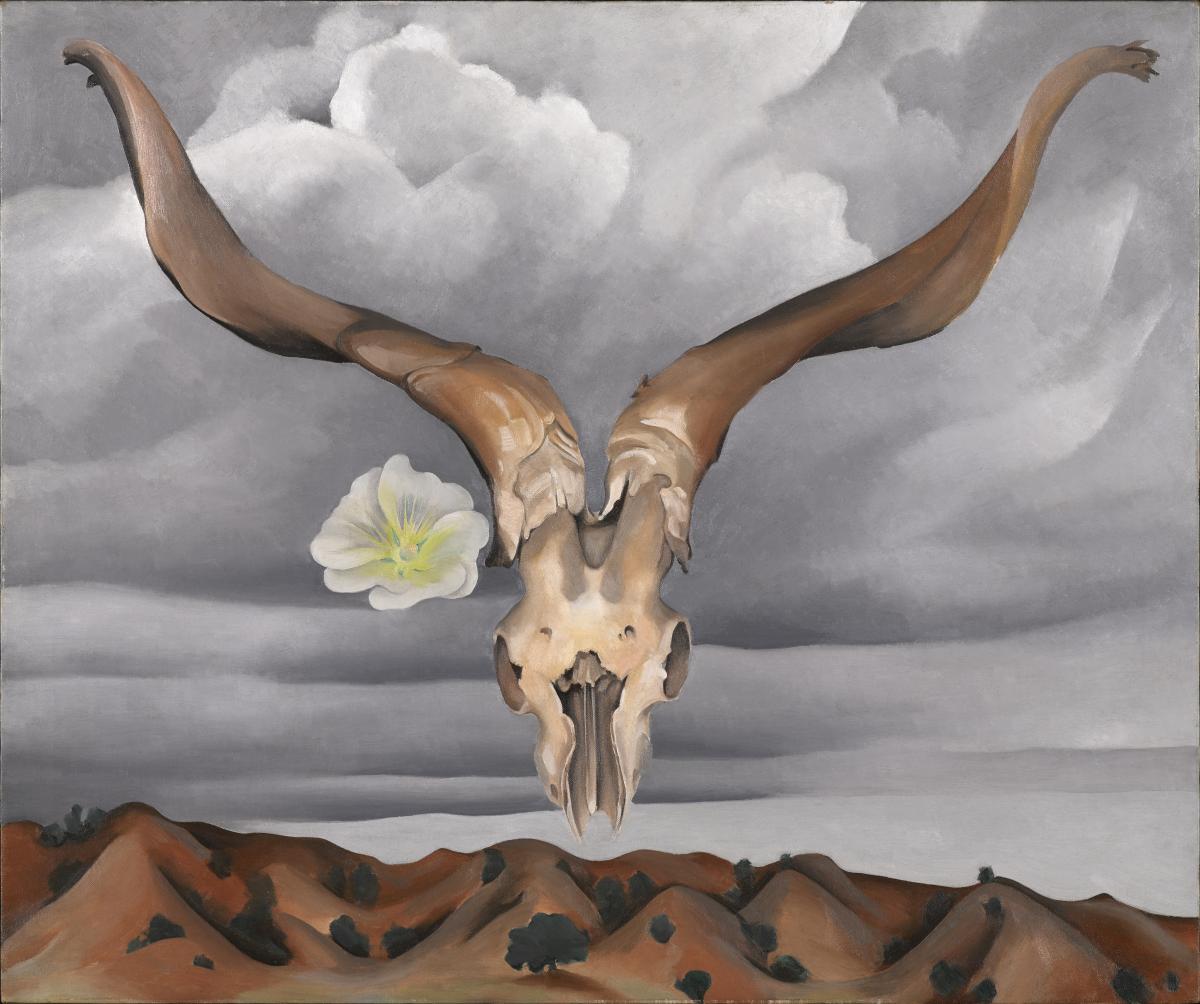

Ram's Head and White Hollycock, New Mexico, 1953

4. OPPOSITES REUNITED

Returning to the south-west in 1929, O’Keeffe insisted that the bones she gathered during her desert walks recalled ‘what endures, what transcends, what is eternal’.

She purposely stripped away all reference to civilisation from her landscapes. Yet there is no hint of gloom, as with the European take on the ‘sublime wilderness’.

Instead, O’Keeffe's views are uplifting.

The inner glow of curvaceous, pinky hills sprouting green sagebrush suggests Mother Earth snuggling under the blanket of storm clouds, draped in grey folds while rejuvenating life. In 1935, this sets the scene for the mysteriously hovering ram’s skull, awakening untroubled to its own esoteric significance beyond death. The hollyhock serves as a comic’s’ ‘thought bubble’, relating the ram’s newly found bliss.

The stunning perennial evokes one of O’Keeffe’s favourite books, The Secret of the Golden Flower – a Chinese text on alchemy translated by Richard Wilhelm (sinologist and theologian), whose ‘great work’ is finding the gold in one’s own heart to purify one’s soul. Its foreword by Carl Jung draws parallels between alchemic symbols and archetypal dream images. Basically, the anima or yin principle is earth-bound and decays. By contrast, the animus or yang principle rises after death. O’Keeffe’s hollyhock and hills become the yin; her ram’s skull and clouds, the yang.

O’Keeffe’s flower images could be sensual, erotic, ecstatic or spiritual. They expressed her volatile relations with Stieglitz, which plunged O’Keeffe into a depression in 1933. Ram’s Head and White Hollyhock, New Mexico announced O’Keeffe’s newest phase of joy and affirmation. She had made her peace with her failing marriage and all personal strivings.

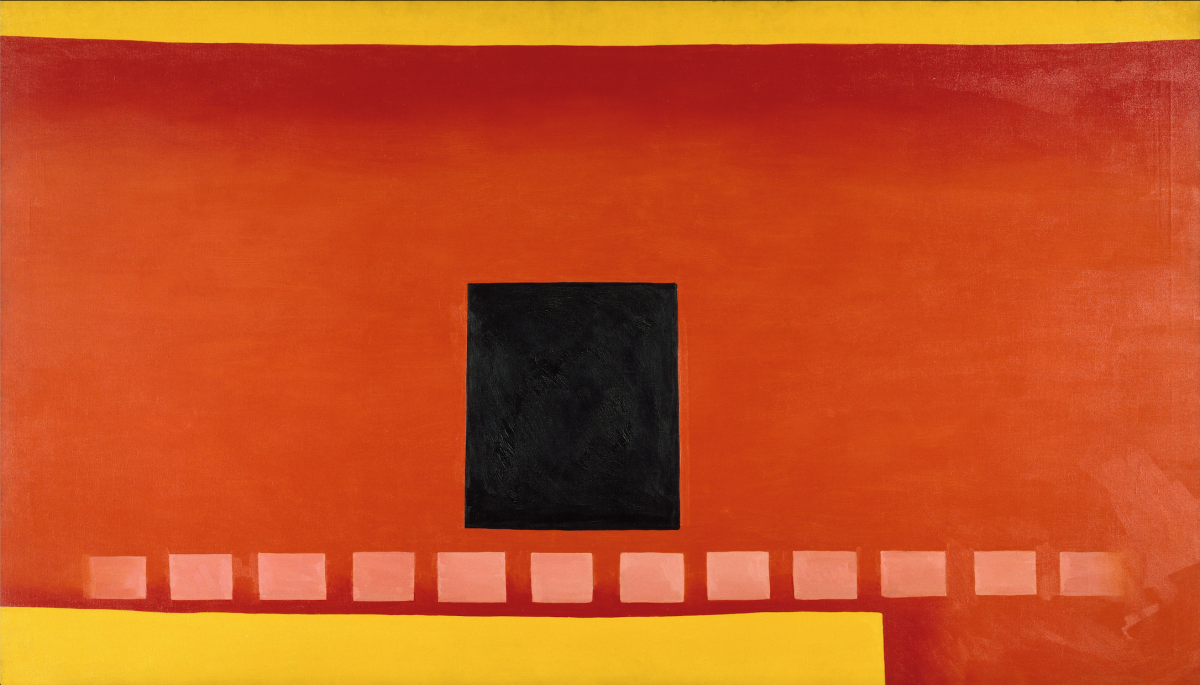

Black Door with Red, 1954

5. PASSAGES BEYOND AND WITHIN

O’Keeffe loved New Mexico and spent more and more time there, purchasing an adobe ruin in 1945 because she just had to have the black door off its courtyard.

She never tired of painting pictures of it.

Her multiple portrayals – with falling leaf, under the snow, or with variously coloured walls – underline the impermanence of all things; for Buddhists, the only truth. The subtle asymmetry of these graceful, enigmatic patio paintings found their minimalist aesthetic from tea ceremonies and Zen gardens.

In 1954 she swore she’d painted her last black door, but she’d paint nine more.

In this view, a blank red plane is, at the same time, an adobe wall; the black square, a threshold to the beyond. It foretells of her close friend Aldous Huxley’s essay, The Doors of Perception. The row of flagstones suggests the dotted line down Route 66.

O’Keeffe had learnt to drive back in 1929 and used a car as a mobile studio/shelter in temperatures of over 100°F, when painting isolated landscapes. Once widowed, she began travelling the world, especially around Japan, India and Peru. The great outdoors always beckoned her. From the aeroplane, she looked down on the land and sketched patterns of riverbeds to later paint and explore, which she did on rafting trips as late as age 78.

By her death, aged 98 in 1986, O’Keeffe had become one of the most successful living artists in the USA. Her extraordinary art lets us see the bigger picture: beyond and within.

|

Georgia O’Keeffe – After Return from New Mexico by Alfred Stieglitz, 1929

DEBORAH'S TOP TIPS

See If travel allows, catch one of the major exhibitions on O’Keeffe in Europe. Georgia O’Keeffe is at Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid until 8 August; Centre Pompidou, Paris from 8 September–6 December; and Fondation Beyeler, Basel from 23 January–22 May 2022.

Read...

...what Georgia O'Keeffe read

...as well as my essays

Visit Many USA cities have O’Keeffe artworks in their collections, including The Smithsonian, Washington DC (28 works); Art Institute Chicago (21); and The Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth (21).

Retrace O’Keeffe’s footsteps Alternatively you can just stay home and meditate on a single flower. Relish its beauty.

|

About the Author

Dr Deborah Jenner

Dr Deborah Jenner is an American art historian who lectures and writes on USA art links with both Europe and Asia. She has published and curated shows on contemporary Indian art. She completed her PhD on The Spiritual in the Art of Georgia O’Keeffe at the Sorbonne in Paris, where she taught and gave city walking tours until her recent semi-retirement. As an Arts Society Accredited Lecturer her talks – besides those on O’Keeffe – include Monet: what he sees is what we get, Behind the surface of Andy Warhol’s work and Rabindranath Tagore’s paintings: Primitivism at the heart of the avant-garde.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition