This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Art of the Chrysanthemums

Become an Instant Expert on the Art of the Chrysanthemums

26 May 2021

As gardens burst into life, now is the time to plant chrysanthemums, to flower later in the year. Once used as a herb, this perennial, says our expert, Twigs Way, comes with both a fascinating history and a deep allure for artists

Chrysanthemums, by Claude Monet, 1897

Chrysanthemums, by Claude Monet, 1897

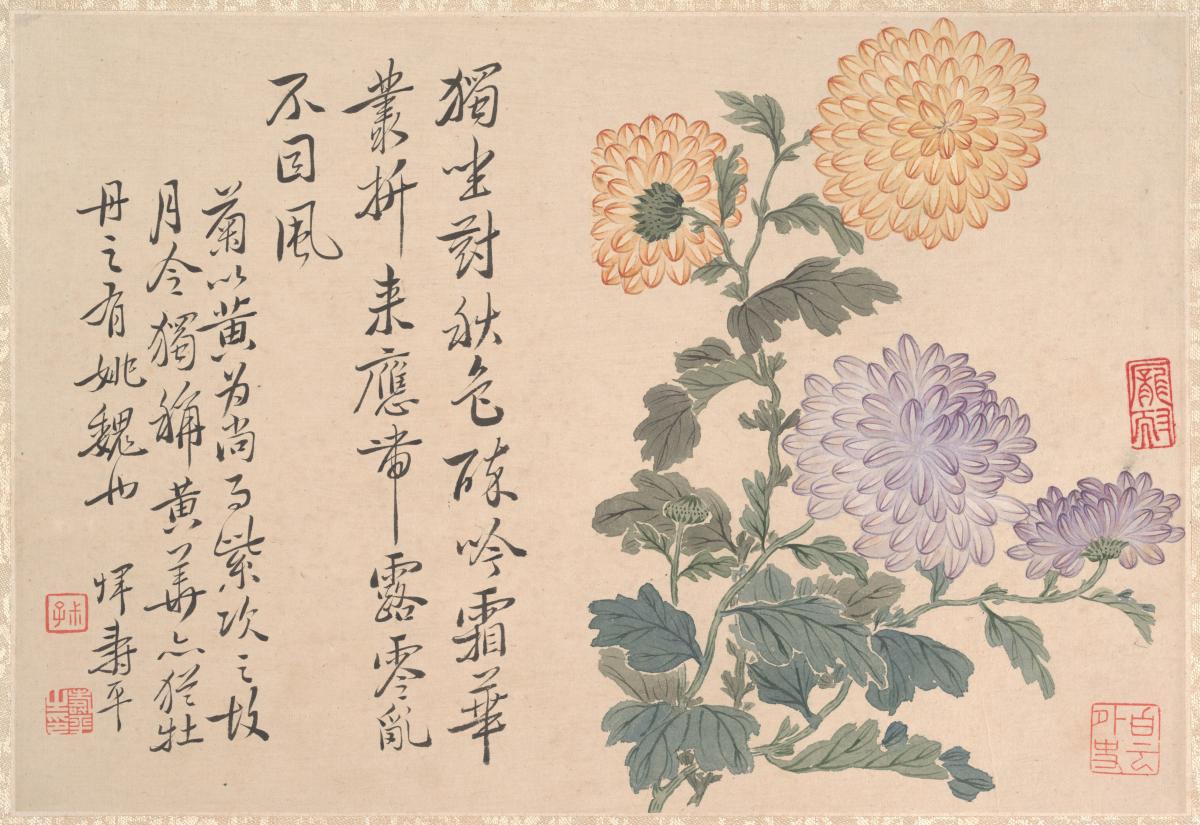

Chrysanthemums, by an unidentified artist from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

Chrysanthemums, by an unidentified artist from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

1. BRINGER OF HEALTH AND HAPPINESS

Asia is the home of the wild chrysanthemum and China the heart of chrysanthemum history. Along with bamboo, plum blossom and the orchid, the chrysanthemum forms one of the ‘Four Gentlemen’ plants that represent the seasons, and cultivation is recorded as early as the Shang Dynasty (c.1600–1046 BC).

As the symbol of autumn, the Chinese chrysanthemum is imbued with the wisdom and life force of the summer that has passed. It brings health and energy to face the winter ahead, especially to those that drink traditional chrysanthemum tea and bring flowers to lay on the revered graves of the ancestors.

Arriving in Japan by the 8th century, the chrysanthemum was embraced as a symbol of the imperial family. Even today the emperor is said to accede to the ‘Chrysanthemum Throne’, while passports and proclamations bear the official seal or symbol of 16 petals – the kikukamon (the Chrysanthemum Flower Seal).

Early Japanese chrysanthemum breeders created an array of complex petal formations and flower heads, which would later fascinate Europeans. Artists of every era were drawn to the plant, from painters to potters, with the simplicity of the original chrysanthemum surviving on ancient Chinese ceramics and the simplest rice bowl.

Chrysanthemums, c.1874–76, by James Jacques Joseph Tissot

Chrysanthemums, c.1874–76, by James Jacques Joseph Tissot

2. IMPRESSIONS OF CHRYSANTHEMUMS

Japanese chrysanthemums, with their varied petal shapes and toning colour range, reached Europe in the mid-19th century and became a favourite flower of the Impressionists.

In 1890 the art critic and chrysanthemum lover Octave Mirbeau wrote to Claude Monet: ‘…next year I’ll make you a collection of chrysanthemums I have which are all wonderful with crazy shapes and beautiful colours, I found them at a brilliant gardeners in Le Vaudreuil.’

Monet’s garden at Giverny housed his collection of chrysanthemums, and everywhere there was evidence of his love for Japonisme, which fed the fashion for chrysanthemums throughout Europe. Within his home, Monet had more than 200 Japanese prints by artists such as Hokusai (1760–1849) and Hiroshige (1797–1858), and Japanese vases appear in some of his paintings of chrysanthemums. It was Japonisme, too, that inspired Monet’s own water garden, with its pont Japonais.

Artist Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94), a fellow gardener and friend of Monet, also grew and painted the plants in his garden at Petit-Gennevilliers. Monet owned Caillebotte’s 1893 painting White and Yellow Chrysanthemums, while Caillebotte acquired a Monet painting of the same subjects.

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (c.1836–1902), the French artist who fled to London after the Paris sieges, brought the artistic fashion for chrysanthemums with him. Living in the then rather louche area of St John’s Wood, London with his Irish mistress Kathleen Newton, he created a range of winter gardens that can be glimpsed in paintings including his Chrysanthemums (1874–76), seen here. There is, however, a mystery as to the name of the female model who appears in this painting, her shawl matching their yellow tones.

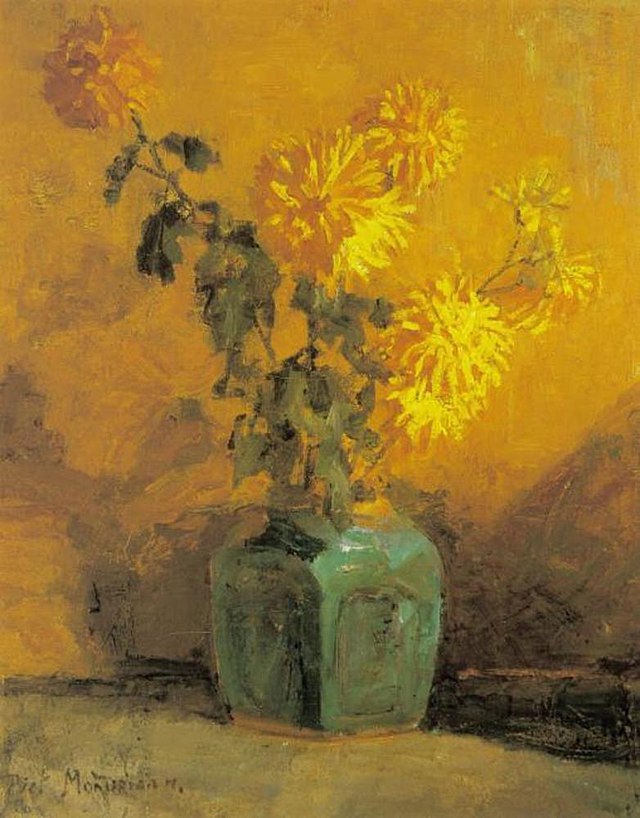

Yellow Chrysanthemums in a Ginger Pot, by Piet Mondrian, c.1898

Yellow Chrysanthemums in a Ginger Pot, by Piet Mondrian, c.1898

3. FEMININE IDEALS IN AN ABSTRACT WORLD?

Better known for his large abstract geometric works in blocks of solid colour, Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) initially embraced the chrysanthemum in his works.

Mondrian was fascinated with the complexity and mass of the plant and usually chose to depict single blooms often on the edge of decay, with drooping leaves and large massed heads slightly unravelling. In these he sought to find the essence both of their ‘plastic structure’ and their hidden inner beauty and purpose.

This search for the interior spirit of the chrysanthemum also led him to create a series of canvasses depicting the chrysanthemum in shades of blue, forsaking their natural colour for what he called ‘pure’ colour.

Recent studies have explained Mondrian’s obsession with portraying the chrysanthemum as the ‘feminine ideal’ in his otherwise rectilinear world, the fulfilment and reflection of his inner life, as an individual and a painter.

An old cast iron mausoleum door in the Montmartre Cemetery in Paris with decoration of chrysanthemums

An old cast iron mausoleum door in the Montmartre Cemetery in Paris with decoration of chrysanthemums

4. GHOSTLY CHRYSANTHEMUMS

It is said that to bring a bouquet of white chrysanthemums into an Italian house is to bring death in its wake, and across much of Europe the chrysanthemum is the flower of death and mourning.

On La Toussaint (All Saints' Day) in France, graves are piled high with pots of chrysanthemums of all colours. The flowers also feature on tomb gates (as seen here), or carved on headstones commemorating the dead.

Composer Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) entitled his elegy to his friend King Amadeo of Spain, I Crisantemi (The Chrysanthemum). It is a work of overwhelming sadness, written for a string quartet, although a later version for a full string orchestra became surprisingly popular, perhaps after the original purpose had been forgotten.

Despite this association with mortality, the Victorian garden writer James Shirley Hibberd (1825–1890) believed that the newly fashionable chrysanthemum shows resulted in a decrease in November suicides. He believed the sunshine colours of the blooms lightened the gloom of winter and brought happiness to all that saw them.

A detail of a Japanese kimono, decorated with chrysanthemums

A detail of a Japanese kimono, decorated with chrysanthemums

5. SCENTLESS MERCHANDISE?

Often described as spicy, earthy and even musty, the scent of chrysanthemums is often confused with the damp autumnal earth that surrounds them; indeed, some would say they smell of the graveyard to which so many bouquets are consigned. When crushed, the leaves do give off an acrid smell, which may have inspired DH Lawrence (1885–1930) to call his 1909 short story on a failed marriage Odour of Chrysanthemums – the bouquets that marked the events of loveless marriage now foretelling a death.

In his 1881 poem Humanitad, Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) seems to have an almost spiritual disappointment at this lack of fragrance, where the ‘Chrysanthemums from gilded argosy / Unload their gaudy scentless merchandise’.

Regardless of the lack of fragrance of the real flower, in 1969 the company Fabergé created a perfume named Kiku, the Japanese for chrysanthemum. Marketed in bright-yellow containers, its packaging reflected the fashion for strident oranges and yellows in textiles and plastics. The perfume was discontinued in 1976, but stray bottles still enjoy a following among collectors.

The association between women and chrysanthemums, which inspired the creators of Kiku, is also reflected in the use of the flower on beautiful kimonos and other rich textiles, as shown in Japanese prints and the textiles themselves.

See

When we can travel again, a key site to view chrysanthemum works is The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), which holds both Caillebotte and Monet paintings of the plant. Japanese prints by Hokusai, Hiroshige and Utagawa Kuniyoshi can be admired either in person or online at museums including, again, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

Visit Monet’s garden in Giverny in France later in the year when crowds are thinner and the autumnal tints at their best. If you go before 1 November 2021, you can also catch the new exhibition, Côté jardin. De Monet à Bonnard, at the nearby Musée Giverny Impressionnismes.

Closer to home, the RHS Malvern Autumn Show is a highlight of the chrysanthemum year.

The V&A (London) has a glorious collection of Japanese textiles, including those with chrysanthemum decorations.

Read

You can read all about the chrysanthemum in art and culture in my book Chrysanthemum, published by Reaktion Books (2020).

About the Author

Twigs Way

Arts Society Lecturer Twigs Way is a garden historian who is fascinated by the crossover in horticulture and art and literature. Her focus includes 18th- and 19th-century female botanical artists, such as Marianne North, garden makers and travellers, and the art and culture of specific flowers, including the golden sunflower and the bronze chrysanthemum. She is currently researching the equally golden daffodil. Among her talks are The divine sunflower in art and culture and Mary Delany (1700–88) and her paper flower art.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition