This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert the art of cartoons

Become an instant expert the art of cartoons

12 Jan 2021

Do you know your manga from your fumetto, your cartone from your caricatura? Read on as cartoonist and Arts Society Lecturer Harry Venning gives us a short history of the art of the cartoon

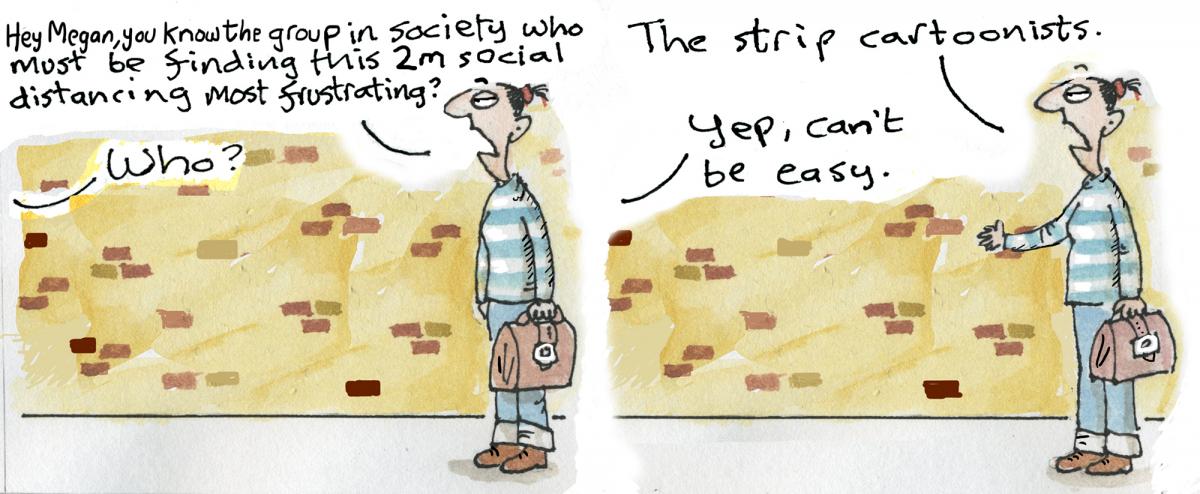

A cartoon for our times by Harry Venning from his Clare in the Community comic strip from The Guardian newspaper

A cartoon for our times by Harry Venning from his Clare in the Community comic strip from The Guardian newspaper

An early work by Leonardo da Vinci

1. FROM LEONARDO TO MR LEECH

The word ‘cartoon' comes from the Italian cartone, meaning a piece of thick paper or card upon which an artist would draw a preliminary sketch for a painting or mural. A fine example of those early cartoons is the work of Leonardo da Vinci – large drawings in charcoal and chalk, as seen above. We are also indebted to the Italian language for the word caricature, from caricatura, which literally translates as ‘an overloading’.

From Italy to London, in 1843 The Fine Arts Commission, which was in charge of the decoration of the new Houses of Parliament, offered £2,000 in prizes for ‘cartoons’ on a subject from British history, with winning entrants exhibited in Westminster Hall. In response, the artist John Leech produced Cartoon No. 1 – Substance and Shadow, which was published in the satirical magazine Punch. The cartoon depicted a crowd of emaciated paupers and waifs attending the exhibition, presenting a stark contrast to their surroundings and the heroically themed artwork on display.

Boosted by Leech’s status as the most celebrated illustrator of the age, the word ‘cartoon’ passed into common usage as denoting a satirical or humorous drawing. Today Leech is largely forgotten, although he still enjoys a small degree of fame as the illustrator of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

The Yellow Kid was one of the most popular strip cartoons of its time

2. THE 'FUNNIES' AND THE CIRCULATION WARS

Strip cartoons became increasingly popular towards the end of the 19th century, particularly in the United States. Predominantly visual, the 'funnies’ found a huge market among the semi-literate urban working classes and the recently arrived immigrants still struggling to learn English.

A middle-class backlash against such supposedly low and vulgar entertainment was inevitable, with one of the most popular strip cartoons of the time, The Yellow Kid, having its name appropriated by critics, who denigrated mass-market publications as ‘The Yellow Press’.

Such snobbery did little to contain the phenomenal growth of strip cartoons as a medium. Market research company Gallup’s inaugural opinion poll found that comic strips were by far the most popular feature in the newspapers. By the early 20th century some US newspapers carried up to 26 pages of comic strips, and they became an integral weapon in the circulation wars between press barons William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer.

Attempts to poach each other’s star cartoonists and most popular strips ended in bitter acrimony, expensive lawsuits and some rich cartoonists, which isn’t a phrase you hear that often.

Several strip cartoons have enjoyed phenomenal longevity. Rudolph Dirks’ The Katzenjammer Kids made its debut in 1897 and, although the final strip was published in 2006, The Kids’ adventures continue to be syndicated throughout the world.

3. THE COMING OF PEANUTS

The most successful cartoonist of all time is Charles M Schulz (1922–2000). At its height Schulz’s comic strip Peanuts, featuring Charlie Brown and his friends, was published daily in 2,600 papers in 75 countries, in 21 languages. Not bad for a person who didn’t go to art school because ‘I couldn’t stand the thought of being in a room full of people who could draw better than me’. Instead he learnt to draw through a mail correspondence class – an education he appreciated so much that he would later return to the school as a tutor.

Peanuts started life as a single-frame cartoon called L’il Folks, published in the St. Paul Pioneer Press. When Schulz developed the idea into a strip it was taken on by United Feature Syndicate, on the condition he change the name, which they thought too similar to a rival strip, Tack Knight’s Little Folks. When he resisted, the Syndicate imposed the name Peanuts upon his work. Schulz couldn’t abide it, thinking it irrelevant and trivial, but the name stuck and became a global brand. Since Schulz’s death, the Peanuts annual revenue has ranged from $80m to upwards of $1bn.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King, a former schoolteacher called Harriet Glickman urged Schulz to introduce an African-American child into Charlie Brown’s friendship circle. Initially reluctant, Schulz acquiesced and, in July 1968, Franklin appeared for the first time, returning Charlie Brown’s beach ball. The public response was largely positive, although it is said that several newspaper proprietors in the South were livid, and threatened a boycott. ‘There weren’t many letters,’ Schulz recalled, ‘but they were quite vehement.’

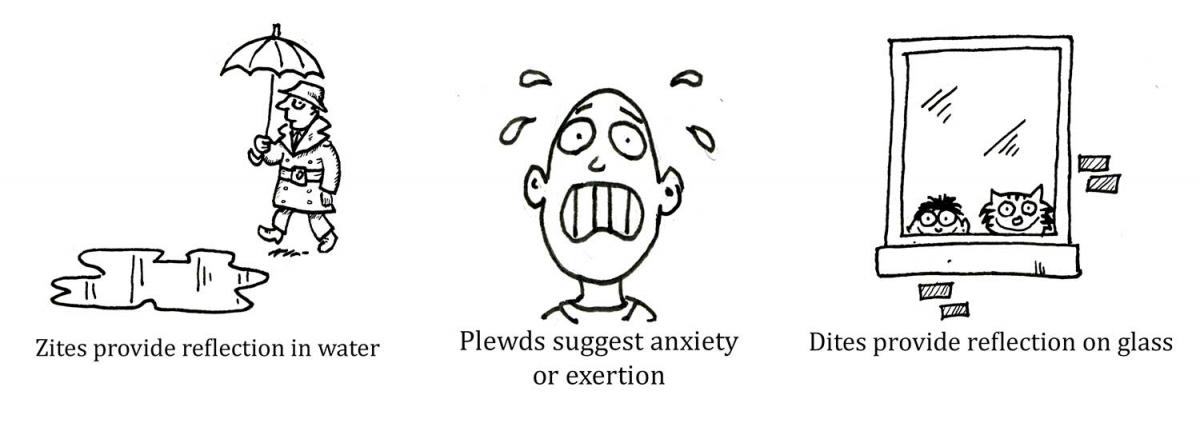

The difference between a zite, a plewd and a dite

The difference between a zite, a plewd and a dite

4. A ZITE, A PLEWD OR A DITE?

Sitting for a portrait in the early days of photography was a laborious and uncomfortable pastime, not least because the subject had to remain perfectly still throughout. The slightest fidget would result in a peculiar ghosting effect – one that cartoonists and illustrators immediately appropriated as a way to convey movement in their pictures.

There are a host of visual tricks and techniques cartoonists use to animate and enliven their otherwise static images, but it wasn’t until 1980 that a glossary of terms was invented to describe them all.

In his 1980 book The Lexicon of Comicana, the cartoonist Mort Walker introduced the world to dites, hites, vites, briffits, plewds, indotherms and other tongue-in-cheek terminologies, many of which caught on. Hites, for example, are horizontal lines, conveying speed, that trail behind an object or a person. If we are talking extreme speed then a briffit, or cloud of dust, would be left hanging in its wake.

For reflections on a pane of glass look no further than diagonal lines called dites. For reflections in water, vertical lines called vites are used (reverse it out, black for white, and you can conjure up oil or even blood). Plewds are the flying sweat droplets around a stressed-out or hard-working character’s head; indotherms represent steam or heat rising.

Grawlixes, meanwhile, are the typographical symbols that stand in for swear words. Somehow grawlixes look even more profane than the words they are replacing, but without giving offence. Which I’m sure you’ll agree is something of a %&*@$ miracle.

The strip cartoon created by Harry Venning for The Guardian, Clare in the Community, with a few grawlixes added for colour

The strip cartoon created by Harry Venning for The Guardian, Clare in the Community, with a few grawlixes added for colour

5. ANOTHER WAY OF SAYING 'COMIC'

Strip cartoons are popular the world over, but only in the English language is the word ‘comic’ used in connection with them.

The French term is bande dessinée (in English, a ‘drawn strip’ or ‘BD’ for short). The older German term is Bildergeschichte (‘picture story’) or Bilderstreifen ('picture strip’). The Italians call the art form fumetto (literally ‘little puff of smoke’ after the speech bubbles used to enclose verbal dialogue), while in the Spanish language both the comic strip and comic book are called historieta, or anecdote.

The Icelandic word teiknimyndasögu is very possibly longer than some of the cartoon strips it describes.

The Japanese are voracious consumers of comic strips, comic books and animation, all of which are covered by the term ‘manga’. This comprises of two parts: ‘man’, meaning whimsical and impromptu, and ‘ga’, meaning pictures.

So, there are very many terms describing the art of the cartoonist for you to draw upon (pun intended). However, there is one that you must never use under any circumstances, but particularly in the presence of a cartoonist: ‘doodles’. Just don’t do it!

HARRY'S TOP TIPS

Find out more about a master on the site of The Charles M Schulz Museum.

Good reads

Michael Chabon’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (published by Random House), set before, during and after World War II (or, as that time is also known, the Golden Age of American Comics). A novel inspired by comic books and comic-book creators.

The Complete Cartoons of The New Yorker (published by Hachette), which comes with a DVD-ROM containing over 70,000 cartoons. Apart from being sublimely funny, the cartoons also provide a social and historical commentary on the past 100 years in the US.

Beloved in his native Australia, though less well known in the UK, Michael Leunig is a cartoonist with a unique and charming drawing style combined with a quirky and compassionate sense of humour. The Penguin Leunig, reissued in 2014 by Penguin, is a great starting point for his work.

Illustrators claim Ronald Searle as their own, but we cartoonists know better. Searle is probably best remembered for his drawings of the schoolgirls of St Trinian's, but I prefer Molesworth, the schoolboy he created with writer Geoffrey Willans. Penguin Modern Classics published a collection of Molesworth in 2000: Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle's Molesworth. It is the best book ever, as, as Molesworth would say, 'any fule kno'.

Visit: The Cartoon Museum, London, home to a collection of more than 6,000 original cartoon and comic artworks and a library of over 8,000 books and comics.

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Harry Venning is an award-winning cartoonist, comedy writer and performer based in Brighton. His cartoons have appeared in publications as diverse as Mathematics Today, Radio Times, Music Teacher and The Stage. For 25 years he has provided The Guardian with the weekly strip cartoon Clare in the Community, based on the misadventures of an empathy-free social worker. In 2004, he developed the strip into a successful BBC Radio 4 sitcom starring Sally Phillips, which ran for 12 series. Among his lectures for The Arts Society are Release your inner cartoonist – the art of storytelling and joke writing in strip cartoons and The art of the cartoonist. For more on his work, see the Harry Venning website or the Clare in the Community website.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT STORY...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

Show me another Instant Expert story

About the Author

Harry Venning

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition