This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Art of Armour

Become an Instant Expert on the Art of Armour

1 Mar 2021

The armour that clad warrior knights of old was not merely worn for protection; each one was a work of art, holding hidden messages denoting power and identity. Arts Society Lecturer Tobias Capwell leads us into this mysterious world of metal

John Chalon of England and Lois de Beul of France jousting, from the Royal Armoury Manuscript, 1448

‘I have known when he would have walked ten mile a-foot to see a good armour…’

William Shakespeare, Much Ado about Nothing

Act II, Scene 3, lines 829-30

The close-helmet of the Emperor Ferdinand I, Augsburg, c.1555, from The Wallace Collection, London

The close-helmet of the Emperor Ferdinand I, Augsburg, c.1555, from The Wallace Collection, London

1. DIVINE POWER IN HUMAN FORM

Medieval and Renaissance Europe was ruled by kings, queens and princes who claimed their right to rule directly from God. The Divine Right of Kings bestowed ultimate power on the monarch, who in turn granted aspects of this God-given supremacy to the nobility who supported them and enforced their rule. In this, the ‘Age of Chivalry’, the enforcers were the knights and the chevaliers, elite aristocratic warriors who were trained to fight on horseback (from the French cheval meaning horse; and chevalerie denoting horsemanship).

The chivalric class, the knights, had a unique role, beyond fighting for their king. They represented living proof of the extravagant claim of divine right. A knight did not simply claim to be more powerful than other human beings. He literally was more powerful, in several crucial ways.

First, as children, knights-to-be had the luxury of time and money to devote their lives to their martial training. From the age of five or six, they were learning to fight with a variety of weapons and also with their bare hands. By their teens, they were skilled martial artists, and their mastery of the lance, sword, axe and dagger gave them a genuine physical superiority over others.

Second, when they were not just training to fight, they were learning to ride horses, for hours every day. Prowess in the saddle placed all the strength, speed and sheer size and weight of the horse at the rider’s command. On his warhorse or destrier, the knight stood, literally, above other people.

Saint George and the Dragon, c.1432–35, by Rogier van der Weyden

Saint George and the Dragon, c.1432–35, by Rogier van der Weyden

2. KNIGHTS IN SHINING ARMOUR

The ability to fight and ride well in battle had been possessed by elite members of diverse world cultures for centuries – what made the European knight different or special?

The answer was that which, after his weaponry and his horse, completed his arsenal of superhuman attributes – something that was at once an advanced military technology and a powerful, expressive art form.

This was the great age of armour.

For most of the medieval period, it was almost impossible to produce large enough plates of ferrous metal to make solid, one-piece helmets and breastplates. Any amount of good iron or steel was valuable, and had to be used sparingly. Even as late as the 13th century, the only plate armour a typical knight had was his head protection, while the rest of his body was covered in padded textile and mail, sometimes reinforced with plates of hardened leather, horn or bone.

Metal plate armour for other parts of the body only began to proliferate from c.1320, first as plates for the knees, shins and elbows. By the middle of the century, upper- and lower-arm plates became common, as well as complete leg armour. By the late 14th century, iron- and steel-producing technology had advanced to the point where much bigger pieces of good-quality ferrous metal could be smelted consistently, making the complete, mirror-polished plate armour of the archetypal knight at last a reality.

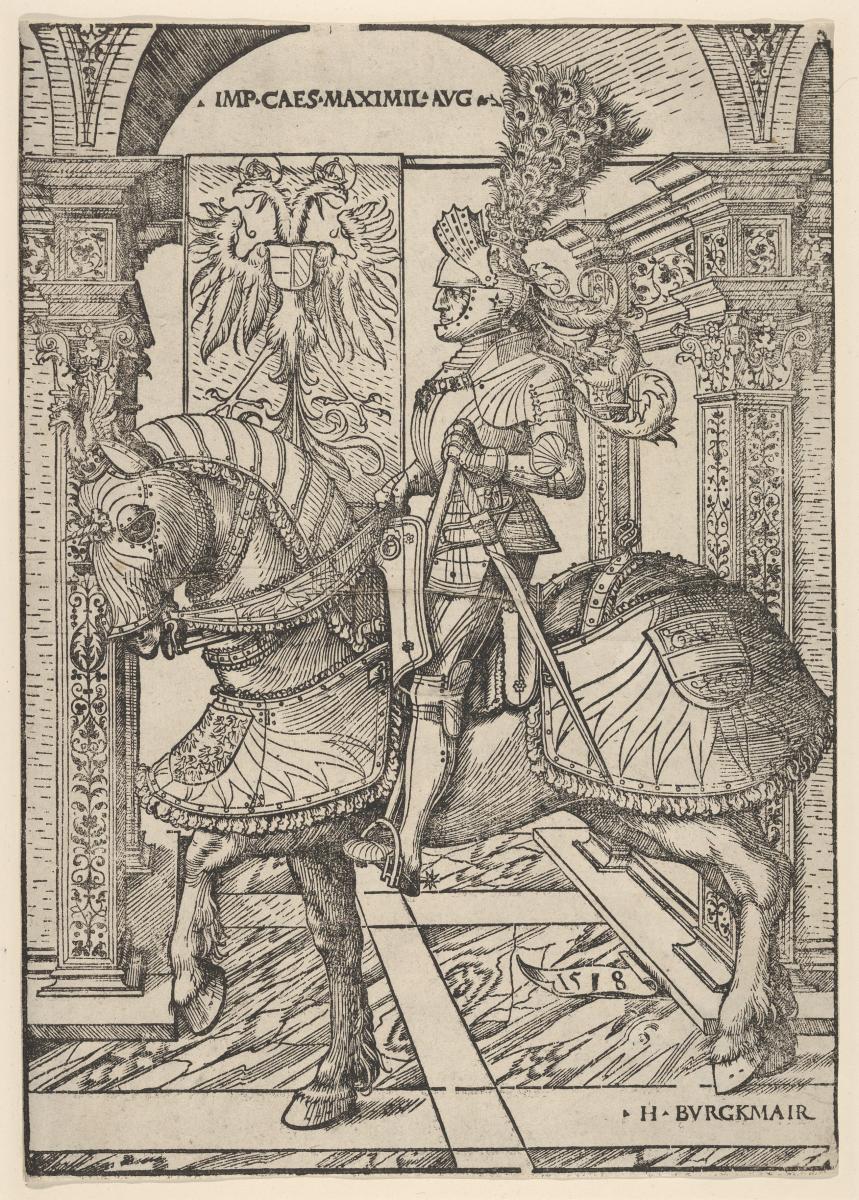

The Emperor Maximilian on Horseback, 1518, by Hans Burgkmair

The Emperor Maximilian on Horseback, 1518, by Hans Burgkmair

3. BODY ART IN FORM AND DECORATION

The complete armour of plate, historically often called a ‘harness’ (but never a ‘suit of armour’) introduced a new art form into Europe.

Armour had always been impressive to look at, and since the earliest times it had been used to broadcast visual messages about the identity, character and associations of the wearer. However, the master armourer of the late Middle Ages became a true artist when he assumed the responsibility of cladding the entire body of his patron in plates of sculpted and polished steel.

At this point, his work took on a new identity as expressive sculpture in metal, possessed of a unity of concept, form and decoration. The great armourers began to self-identify as artists first and military engineers second. They became members of the wider artistic community of the Renaissance, employed in the royal courts of Europe and collaborating closely with draughtsmen, painters and designers – Botticelli painted elaborate tournament shields for the Medici in Florence, and Dürer designed complex visual schemes to decorate the personal armours of the German Emperor Maximilian I.

Armour became a process through which the artist transformed his patron into a living artwork, transforming his physical presence and augmenting his visual impact on the world around him. In this way, armour was of profound and deeply personal significance to the people who funded the Renaissance – the warlike aristocracy and their supporters.

Field armour, made by Kolman Helmschmid of Augsburg and etched by Daniel Hopfer, c.1525, from The Wallace Collection

Field armour, made by Kolman Helmschmid of Augsburg and etched by Daniel Hopfer, c.1525, from The Wallace Collection

4. THE LATEST FASHION IN...

Armour design varied enormously in different parts of Europe. First, it had to be optimised according to local fighting styles and tactics. In the 15th century, for example, English knights tended to fight on foot, while Italians usually preferred combat on horseback. Therefore, each had their own distinct technical requirements. However, different styles arose for aesthetic reasons too – fashionable tastes also varied from region to region.

In Augsburg, the Helmschmid family of armourers created some of the finest examples of the German High Gothic style – a gracile fashion characterised by sharp ridges hammered into the plates, and elaborate pierce-work. This style was supplanted in the early 16th century by a burlier trend, developed by Emperor Maximilian in collaboration with his court armourer at Innsbruck, Konrad Seusenhofer.

The ‘Maximilian’ style combined deep, muscular forms with tight bunches of vertical flutes. By 1520, German masters had perfected the very impressive ‘puffed and slashed’ or Landsknecht style. The Landsknechts were German mercenaries famed for their outrageously voluminous and colourful clothes, and Maximilian’s armourers rose to the challenge of recreating this fashion in steel, rather than textile.

Milan had been another of Europe’s great centres of armour-making since at least the 14th century. In the 15th century the Milanese style was famous for its purity of form, its sculptural elegance and its simplicity. In the 16th century, in direct competition with the Helmschmids, Milanese armourers, led by the Negroli family, created the ‘Heroic’ or all’antica style, which combined Greco-Roman themes with the latest techniques for sculpting and decorating steel.

Detail of the garniture of George Clifford, Third Earl of Cumberland, from the Greenwich royal workshops under Jacob Halder, c.1586; this is now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Detail of the garniture of George Clifford, Third Earl of Cumberland, from the Greenwich royal workshops under Jacob Halder, c.1586; this is now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

5. THE MEANING IN THE DETAILS

The end of the 15th century brought the introduction of etching, a technique for decorating metal by selectively eating the surface away with acid. This greatly expanded the possibilities of armour as a decorative art form.

The greatest etcher of the German Renaissance, Daniel Hopfer, worked for the Helmschmids in Augsburg and is also credited with inventing the process of printing with acid-etched plates, allowing him to publish his designs for armour ornamentation.

Etching looked fabulous on its own, but true decorative ingenuity was found in combining it with sculpting techniques such as embossing and chasing and surface treatments including fire gilding, heat bluing and even enamelling. The diversity of decorative processes that became available in the 16th century allowed for endless combinations, yielding new styles, decade by decade.

Towards the end of the 16th century, the royal armour workshops founded at Greenwich by Henry VIII reached their golden age under Elizabeth I, when the queen’s armourers synthesised the perfect equilibrium of pure sculptural form and breathtakingly flamboyant surface decoration.

Perhaps their greatest masterpiece is the armour made for George Clifford, Earl of Cumberland and Queen’s Champion, seen here. Proclaiming the earl’s unique status, this armour is festooned with Elizabeth’s royal badges – the Tudor rose and the lily of France – as well as her personal ‘E’ monogram, repeated many times, and surrounded by twisting arabesques and lover’s knots.

The great masters of the armourer’s art were always deeply considerate of the distance between their work and the viewer. A work of armour art had to look amazing from a great distance, from across a battlefield or in the tournament lists, but it was also designed to evolve visually as the viewer approached.

From 100ft, bold embossed forms became visible; from 30ft, fine etching revealed itself. From 10ft or less, we become aware of the tiniest details – the filework on buckles, or the piercing along edges.

This is an art form, often misunderstood as purely the technology of war, that will reward longer and closer attention.

See

Many of the world’s great art museums have important collections of medieval and Renaissance armour. These include:

- In the UK: London – The Wallace Collection holds one of the greatest medieval and Renaissance armouries in the world. See specifically the following web pages: armour as Renaissance art and armour materials and techniques. Leeds – a national collection of arms and armour is held at The Royal Armouries.

- In the USA: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago

- In Europe: The Real Armería, Madrid, Spain; The Musée de l‘Armée, Paris, France; the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria; the Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin, Germany; and the Museo Nazionale del Bargello and the Stibbert Collection, Florence, Italy.

- Many of these collections now also have fantastic online study resources.

Good reads

- European Armour: c.1066–c.1700, by Claude Blair (published by Batsford)

- The Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I, by Pierre Terjanian (published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- The Art of Power: Royal Armor and Portraits from Imperial Spain, by Alvaro Soler del Campo (catalogue / National Gallery of Art, Washington)

- Heroic Armour of the Italian Renaissance: Filippo Negroli and his Contemporaries, by Stuart Pyhrr, José Godoy and Silvio Leydi (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- My own published works include Armour of the English Knight 1400-1450 (published by Thomas Del Mar Ltd), Masterpieces of European Arms and Armour in the Wallace Collection (published by The Wallace Collection), Arms and Armour of the Medieval Joust (published by the Royal Armouries) and Henry Moore: The Helmet Heads (published by Philip Wilson Publishers)

Credit: © Ram Shergill.

Credit: © Ram Shergill.

Our expert’s story

Tobias Capwell, BA, MA, MA, PhD, FSA is an author, lecturer and broadcaster, and curator of arms and armour at The Wallace Collection in London. He has also been a rider and martial arts practitioner since childhood, and is a founding member of the modern historical jousting community. He has written many books and articles on weapons, armour, tournaments and knighthood. His lectures include Mars and the Muses: The Renaissance Art of Armour; Beautiful Monsters: Heroic and Grotesque Armour of the Italian Renaissance; and The Scoliotic Knight: Reconstructing the Real Richard III. In 2015 he had the honour of serving as one of the two fully armoured horsemen who escorted the remains of King Richard III from the battlefield at Bosworth to their final resting place in Leicester Cathedral.

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

About the Author

Tobias Capwell

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition