This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on…winter paintings

Become an Instant Expert on…winter paintings

20 Dec 2022

Snow laden branches; a frozen lake in twilight; gleeful skaters on the ice… winter paintings are one of the joys of art history. They are also one of the most challenging genres to represent – with snow being difficult to capture convincingly. Our expert, Stella Grace Lyons, examines how artists have captured our frostiest season

Purchase, Morris K. Jesup Fund, Martha and Barbara Fleischman, and Katherine and Frank Martucci Gifts, 1999

Winter Scene in Moonlight by Henry Farrer, 1869

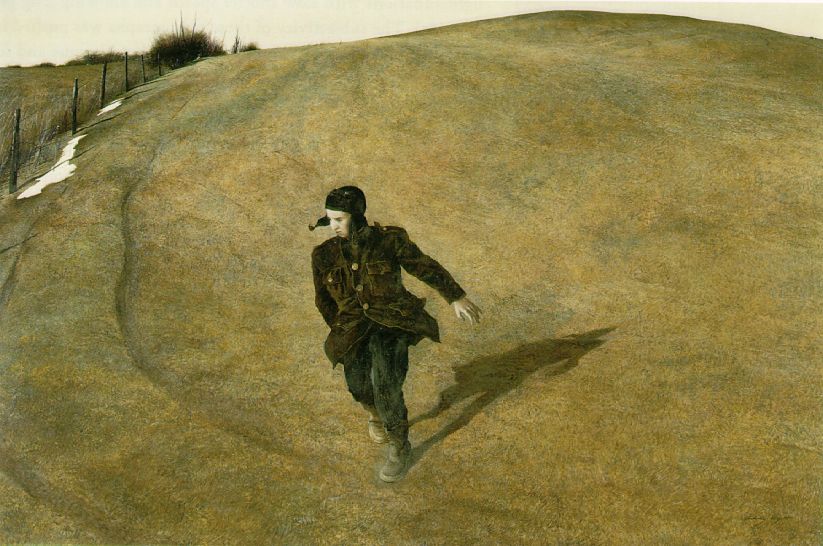

‘I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape – the loneliness of it, the dead feeling of winter. Something waits beneath it; the whole story doesn't show’

The 20th-century realist artist Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009) on painting winter

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ground-breaking work The Hunters in the Snow,

1. A NEW GENRE – THE SNOW SCENE

Bruegel the Elder’s 1565 The Hunters in the Snow is one the best-loved winter paintings in the entire history of art. Its image has graced thousands of postcards, jigsaw puzzles and even masks (perfect for the Covid era!). But before you dismiss the painting as ‘chocolate-box’ worthy, it’s important to understand its significance in the history of winter paintings.

Bruegel was the first artist to paint a fully realised winter landscape. When he painted The Hunters in the Snow, he created an entirely new pictorial tradition – the snow scene. This is a relatively ‘modern’ genre, as most art history genres date back to classical antiquity.

The painting forms part of a masterly cycle of the Labours of the Months, a series showing the different agricultural activities that took place during the year, created for the suburban villa of the Antwerp trader and collector Nicolas Jongelinck. As he dined, he could admire the paintings of peasants on his walls (and presumably thank his lucky stars that he was in a privileged enough position to avoid that sort of toil).

What makes this work a masterpiece? For me, it’s Bruegel’s skilled combination of a harmonious composition, a simple, muted colour palette, and his warm interpretation of humanity.

Bruegel presents us with contrasting aspects of winter. On the raised ‘balcony’ to the left, hunters trudge through the snow after a poor catch. Wood smoke hangs in the air and the tawny dogs, with their stylised curling tails, contrast with the brilliant abstraction of snow.

Bruegel draws our eyes dramatically through the landscape, through naked silhouetted trees and darting birds. Here, despite the bitter cold, the villagers frolic and play. One unfortunate skater has fallen face first onto the ice. Many have marvelled at the charm of this part of the work – it pulls us closer to the past and makes us realise we are not so different from this 16th-century community.

Bruegel continued to paint winter scenes throughout his life, and his paintings of the season have influenced scores of artists. In the next century, he had many imitators, including the Dutch artist Hendrick Avercamp, who became a specialist in winter scenes. He, like Bruegel, presented contrasting aspects of winter, showing entire towns out on the ice, skating, working, hunting and relieving themselves against trees – look out for the trademark bare-bottoms in his paintings.

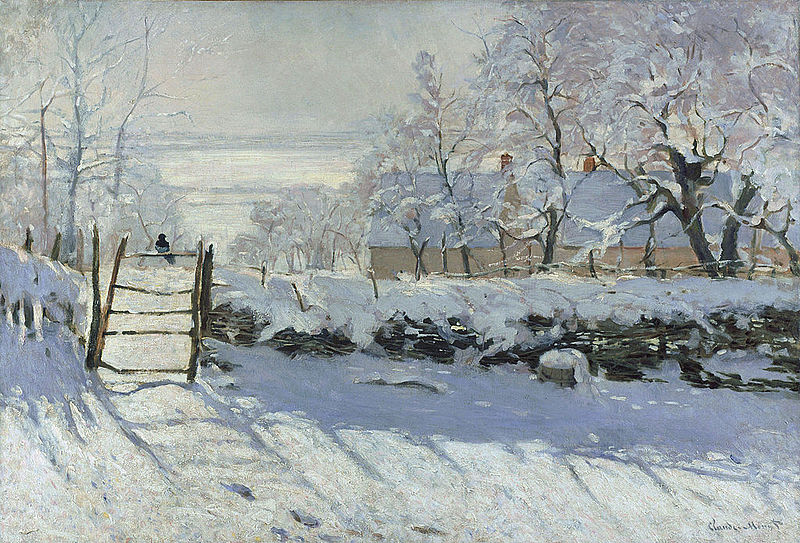

Claude Monet’s atmospheric snowy scene, The Magpie

2. WINTER AS AN ARTISTIC EXPERIMENT

Bruegel’s paintings of winter continued to set the precedent for the winter scenes that followed. But by the 19thcentury, a dramatic change occurred. The joyful skaters of Bruegel’s work gave way to a starker interpretation of the season. The human presence was stripped away and nature took centre stage.

This change is first visible in the work of German romantic artist, Caspar David Friedrich. While it is possible to spot human figures in Friedrich’s winter landscapes, they are usually swamped by their vast environments. Friedrich used the bleak winter landscape to explore ideas about death, resurrection and renewal.

Later in the century, in France, the winter landscape was again used as an artistic device, this time to depict the transitory effects of light and atmosphere, and to investigate the painting of shadows.

In 1868, Claude Monet strode out into the snow near his new home in Étretat and painted a work that proved so controversial that it was rejected at the Parisian Salon. To a 21st century viewer The Magpie looks charming and cosy; not particularly progressive or challenging. What was so offensive about it?

As the art critic John Berger reminds us, ‘Monet once revealed that he wanted to paint not things in themselves but the air that touched things – the enveloping air’.

That’s the impression Monet gives us here. The foreground is entirely snow and shadows. And not just any shadows; they are coloured shadows. By painting shadows in this way, he challenged the established convention of painting them black. The public were not ready for such a progressive idea.

The critic Felix Fénéon wrote at the time: ‘[The public] accustomed to the tarry sauces cooked up by the chefs of art schools and academies, was flabbergasted by this pale painting’.

Today The Magpie is one of the favourite works in Paris’ Musée d’Orsay. At the time however, like Bruegel’s The Hunters in the Snow, the painting was ground-breaking.

Monet would not stop there – he painted around 140 snowscapes during his career. His winter works, as well as those by Sisley and Pissarro (who wrote that when he looked at snow he saw ‘pinks and lilacs in the shadows’) are essentially artistic explorations – essays on the variations of white and the colour of shadows.

The Norwegian artist Harald Sohlberg’s Winter Night in the Mountains

3. SCANDINAVIAN MOOD PAINTINGS

At the same time Monet et al were busy with their coloured shadows, Scandinavian artists were interpreting the winter landscape in an ethereal, dreamlike and mystical manner. We are exposed to relatively few Scandinavian works in the UK, but there’s a plethora of gems to discover from this part of the world. Unsurprisingly, given the Nordic climate, many are winter scenes.

During the 19th century, Scandinavian artists used the winter landscape to investigate ideas about national identity, and to draw attention to their deep connection to the natural world. These works, which capture the unique clarity of the Nordic light, are today referred to as ‘mood paintings’.

They are linked by an almost religious veneration of nature – beautiful, bracing panoramas that show swathes of unspoilt land, often devoid of human life. For the Scandinavian painters working at the end of the 19th century, nature became symbolic for an emotional experience; the painted landscape reflected the landscape of the soul.

Stylistically, these works are varied. Swedish painter Gustaf Fjæstad's delicate visions of winter are filled with pale, glowing light that emanates from the canvas. His snow-covered forests and glistening lakes are painted with a highly decorative, almost pointillist approach.

I prefer the moody works of Norwegian painter Harald Sohlberg. Sohlberg’s magnum opus is the beguiling Winter Night in the Mountains. He discovered the motif while on a skiing trip in Norway’s Rondane National Park. He spent two years working on the theme, and wrote: ‘The longer I stood gazing at the scene the more I seemed to feel what a solitary, pitiful atom I was in the endless universe. I grew uneasy. […] It was as if I had suddenly awakened in a new, unimagined and inexplicable world. […] Above the white contours of a northern winter stretched the endless vault of heaven, twinkling with myriads of stars. It was like a service in some vast cathedral.’

The blues in Winter Night in the Mountains pulsate to form a mystical, timeless vision of nature. There is a spirituality to this interpretation of winter, supported by Sohlberg’s comment that looking at the view mimicked ‘a service in some vast cathedral’. Interestingly, he was not a religious man. His religion was nature and here, he encourages us to adulate alongside him.

Tom Thomson’s Northern Lights, 1917

Tom Thomson’s Northern Lights, 1917

4. PAINTING THE NORTHERN LIGHTS

For many, winter conjures up visions of long dark nights. With these come the hope of witnessing the natural phenomenon, the aurora borealis.

Despite its obvious aesthetic appeal, surprisingly few artists have attempted to capture the northern lights on canvas. One who did was the celebrated American landscape artist Frederic Edwin Church, who painted the aurora borealis using shimmering colours in a grand, striking painting from 1865. His work is in complete contrast with Peder Balke’s, a Norwegian painter who travelled up to Norway’s desolate Northern Cape. There Balke scratched the beams of the lights into explosive little studies, unexpectedly in monochrome.

For me, Tom Thomson’s paintings of the northern lights are the finest. Thomson was a beloved contemporary of the Canadian Group of Seven, a progressive group of painters working in early 20th-century Canada from 1920 to 1933. Thomson didn’t begin painting until around 1910 –11, when he was in his thirties. The catalyst that launched his career was his discovery and subsequent love affair with Ontario’s Algonquin Park.

He spent each summer painting outdoors in Algonquin, creating small, portable sketches. They consist of vibrant pigments expressively painted onto un-primed board, sometimes so quickly that the wood is still visible.

Northern Lights, from 1917, expresses the essence of Thomson. He painted this work from life, in the park. We know a little about how he worked in the snow; he would rush outside, look at the lights, rush inside, warm up his hands and paint. The resulting work is not neat, it’s not tidy, but it captures the raw nature of Algonquin. It conjures up an image of a solitary, focused artist engulfed by the beauty and wilderness of his natural surroundings.

Thomson created around 400 sketches in his lifetime. He would have made more but his life was cut dramatically short. He died in 1917, aged 39, in deeply mysterious circumstances. Whether Thomson was murdered, committed suicide or accidentally banged his head while falling out of his canoe, no one knows. His body re-emerged nine days later in Algonquin Park’s Canoe Lake.

This was one of his final works, and as a result, has a particular poignancy to it.

Winter, 1946, by Andrew Wyeth

Winter, 1946, by Andrew Wyeth

5. WINTER AS A SYMBOL OF LOSS

Countless artists and writers have used the season of winter as a metaphor to explore the themes of death, loss and grief.

These themes are best expressed in the work of American artist Andrew Wyeth, who painted numerous winter paintings during his long career spanning the 20th century.

All Wyeth’s paintings are imbued with a deep sense of nostalgia and poetry. He viewed the world through a melancholic lens. Of all the seasons, he preferred winter because the season exposed, he said, ‘the bone structure of the landscape…Something waits beneath it; the whole story doesn’t show’. This visceral description suggests the hibernation, the shutting down of nature. It brings to mind the next season, spring, lurking below the seemingly harsh landscape.

In 1946, Wyeth painted his moving work, simply entitled Winter. It was an extremely personal feat of mental strength, as this was the first work he made after the death of his father, N.C. Wyeth. N.C. was a highly respected artist who had taught Andrew Wyeth and was his biggest supporter and critic. He was tragically killed when his car stalled on the railroad behind the hill shown in this painting.

Wyeth said about his painting Winter: ‘It was me at a loss – that hand drifting in the air was my free soul, groping. Over on the other side of that hill was where my father was killed, and I was sick I'd never painted him. The hill finally became a portrait of him.’ Wyeth even said that when he painted the hill, he could almost hear his father breathe.

Here Wyeth uses the season of winter as a metaphor for loss and longing. The painting is stark, the landscape bleak. But, like many of Wyeth’s paintings, there is a contrast to this bleakness. Wyeth has painted a detailed depiction of each blade of grass, made possible by his foray into the medium of tempera. The effect is beautiful. The boy in the painting, symbolic for Andrew Wyeth, blends into the hill, symbolic for N.C. Wyeth – father and son are linked forever in this painting.

This painting may not be the most obviously ‘wintery’ of my selection (in fact, there’s just a sliver of snow) but, for me, it is the pathos and sadness that makes it such a compelling work. The artist’s grief seeps through the entire landscape.

Visit

- Norway’s recently opened National Museum to see Harald Sohlberg’s Winter Night in the Mountains and a wonderful selection of Norwegian paintings.

- The Musée d’Orsay in Paris to see Monet’s The Magpie

- Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum to view Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow

- The National Gallery, London to see Caspar David Friedrich’s Winter Landscape and a selection of winter paintings by the French Impressionists.

Online

Join Stella for the following online talks, which can be booked via stellagracelyons.co.uk

17 January: Beer, Batter and Brawling: Pieter Bruegel the Elder

20 January: Magic Realism in New England: the mesmerising work of Andrew Wyeth 24 January: Tom Thomson and the Magnificent ‘Group of Seven’ -

Great reads

Winter – Highlights from the Tate Collection by Kirsteen McSwein

Winter: Five Windows on the Season by Adam Gopnik

Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige by Charles S Moffett

About the Author

Stella Grace Lyons

Stella Grace Lyons BA, MA is a freelance art history lecturer, speaker and writer and an accredited lecturer with The Arts Society. She has lectured across the UK, Ireland, Spain, Norway, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy and Malaysia. She has studied Renaissance art in Italy at the British Institute of Florence, and Venetian art in Venice. In addition, she attended drawing classes at the Charles H. Cecil studios in Florence, a private atelier that follows a curriculum based on the leading ateliers of 19th century Paris. Stella runs online lectures, ‘Stella Talks’, which has listeners from across five continents. She is also a regular lecturer for travel companies, London-based private members’ clubs and small, boutique cruise ships. For more information see her site (as above).

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition