This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on…Australian Aboriginal art

Become an instant expert on…Australian Aboriginal art

19 Feb 2024

Australian Aboriginal art is one of the most fascinating art forms in history. Rebecca Hossack, expert in this field, reveals the key things you need to know about the medium

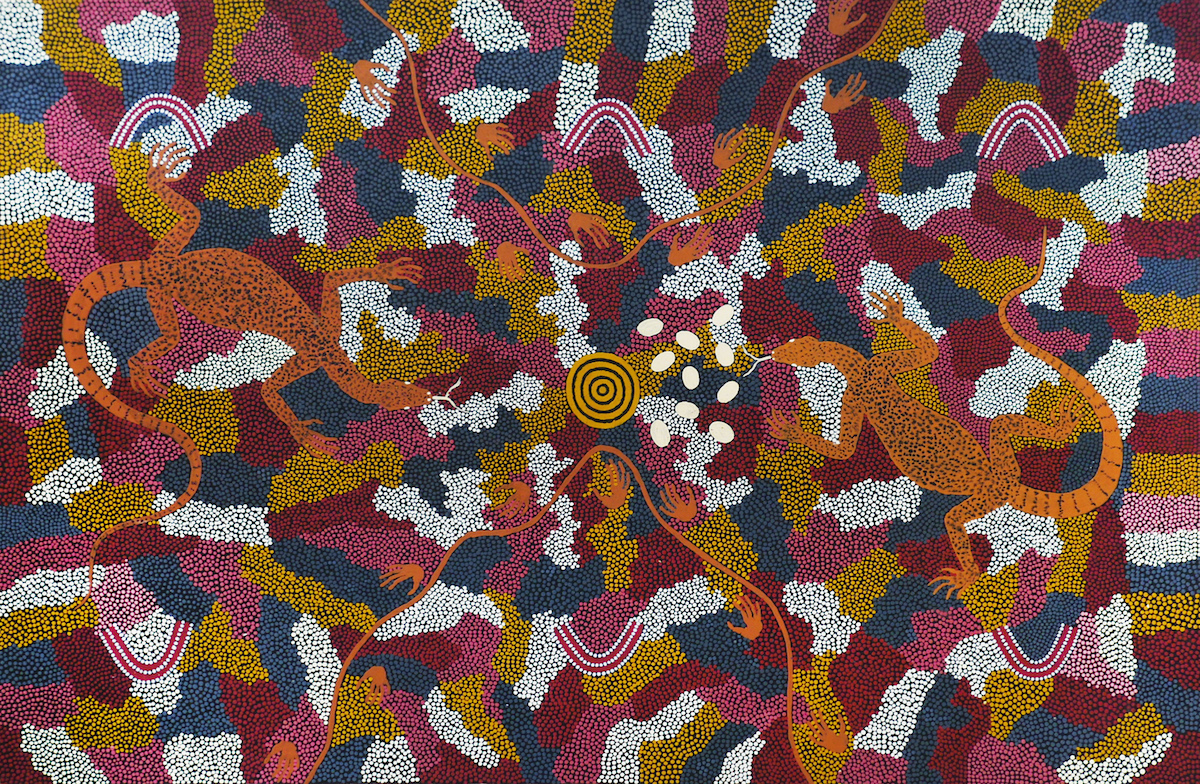

Untitled by Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (c.1932–2002). Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Untitled by Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (c.1932–2002). Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

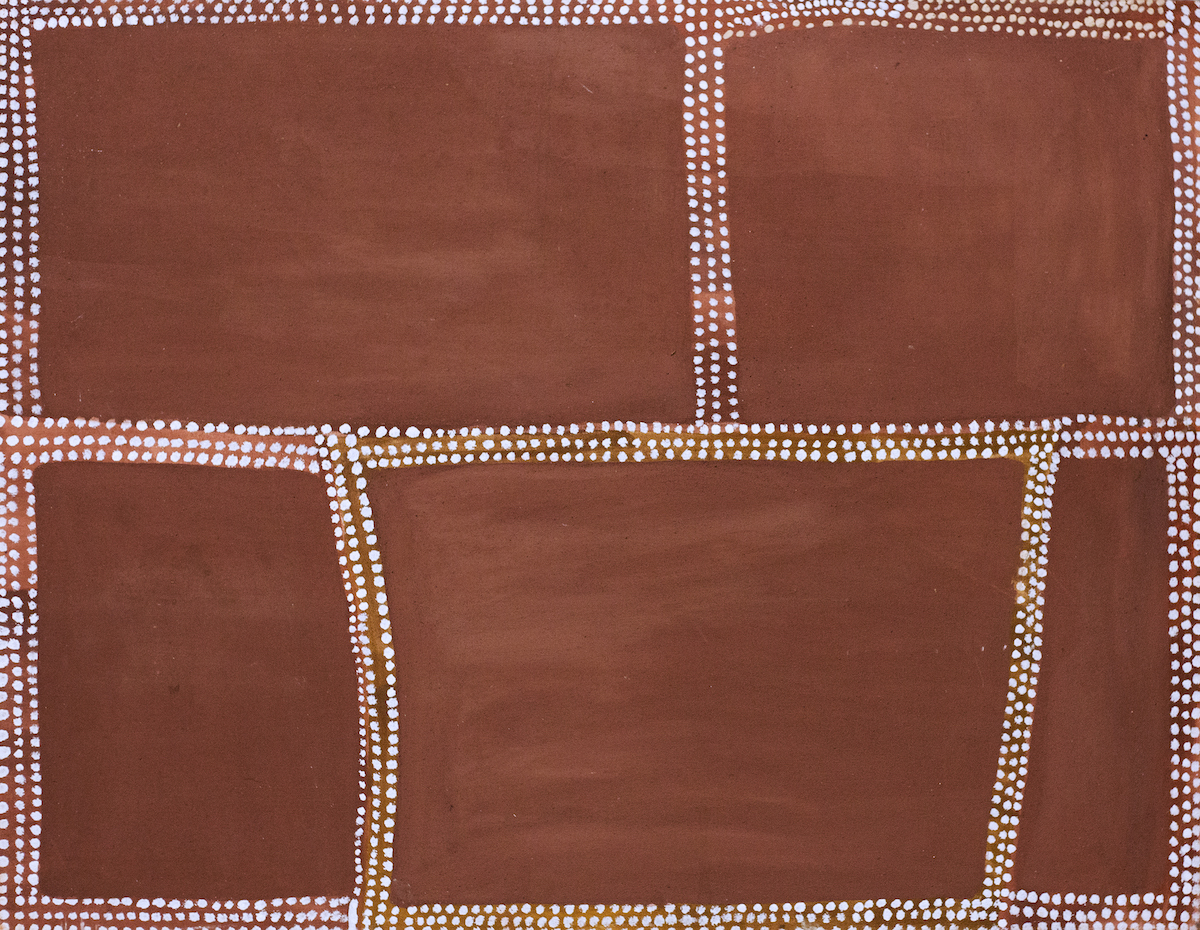

Rock Art (i), Askin (Ric) Morrison. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Rock Art (i), Askin (Ric) Morrison. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

1. Then and now

One of the most important things to know about Australian Aboriginal art is also one of the most curious: this is an art form that is both the oldest continuous artistic tradition in the world, and one of the newest ‘art movements’ in contemporary culture.

It’s a story that can be traced back over thousands of years. There are rock paintings and rock carvings from over 40,000 years still extant in Australia. Among them is the earliest known representation of a human face. This two-toned petroglyph, or stone carving, was found, with many other extraordinary carvings, at a remote site on the Burrup Peninsula on the coast of Western Australia.

Most of the art created by Australian Aboriginal people during past millennia was ephemeral. It was painted on the body (using natural ochres), arranged on the ground (using seed pods and feathers), or carved into living tree trunks. This art was just one element in a traditional ceremonial life that also included dance and song.

It is only in the past half century that such traditional imagery has begun to be set down in permanent and portable form using modern media, such as acrylic paint and canvas.

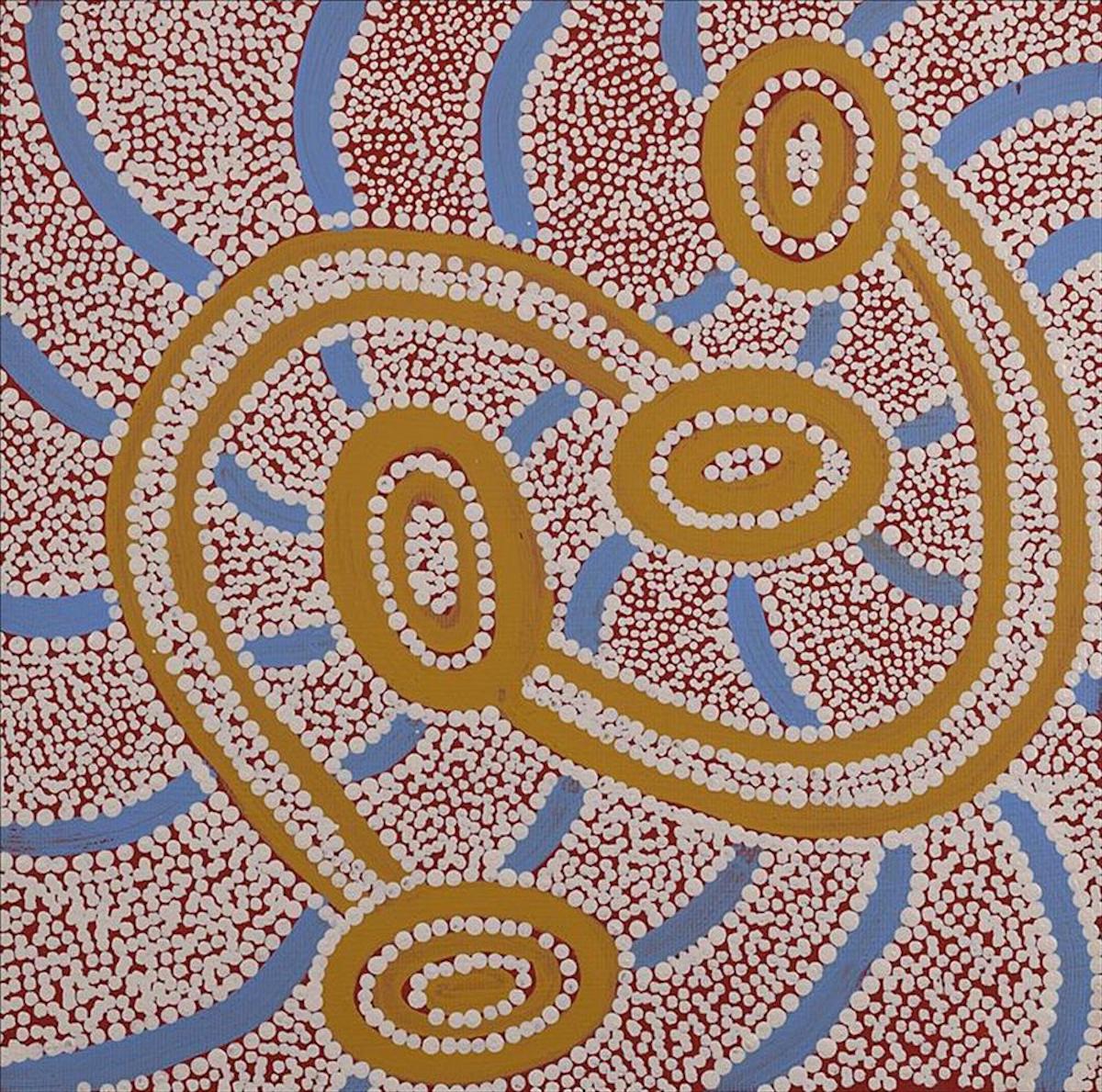

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri’s Tingari Cycle, 1997. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri’s Tingari Cycle, 1997. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

2. Land and identity

The second major thing to know is that Aboriginal Australia is not a single entity. It’s a vast continent made up of many nations with different languages, cultural traditions, stories and iconographies.

Before Europeans arrived in Australia in the 18th century there were some 300 different Aboriginal language groups, each with its own distinct cultural customs. That number has been greatly reduced, but the richness and diversity remains and has evolved in new ways.

Perhaps the best analogy is to think of the continent of Europe. Just as we can all recognise differences between the artistic traditions of Italy, France, the Low Countries, Sweden and so on, so it is possible to distinguish between the art of the Yolngu people (say), of Arnhem Land, in the north of Australia, and the Warlpiri people of Yuendumu in the Central Desert.

Aboriginal art invariably represents both a specific area of land and the story of how that land was created by mythological creatures during what we generally call the Dreamtime. Almost all the paintings made by Aboriginalartists from the many desert communities, across the ‘red centre’ of the continent, use an aerial perspective, to give a highly schematised ‘bird’s-eye view’ of the land. The images may be made up of dots and circles and have a pleasing abstract quality, but all the pictorial elements have representational significance. The ‘U’ shapes, for instance, which often occur in compositions, represent people sitting down, as this is the shape left, imprinted in the sand, by the human bottom.

Tracks, 1994, by Rover Thomas Joolama. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Tracks, 1994, by Rover Thomas Joolama. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

3. A new movement begins

As we know, the story of Aboriginal people in white Australia has not been a happy one. It was not until 1967 that – following a referendum – they were given citizenship in their own land. Before that date they had been regarded as ‘wards of the state’. They were unable to own property or control their own money; they were not allowed to marry or travel without permission. If they lived in or around white communities they were segregated, unable to use community swimming pools, or to sit where they chose in a cinema.

Following the 1967 referendum, the Australian government began a policy of establishing settlements in remote desert areas; the thinking was to induce Aboriginal people to give up their nomadic lifestyle and to introduce them to Western ways of living.

It was at one of these communities, established at Papunya, some 150 miles northwest of Alice Springs, that the contemporary Desert Painting Movement began in the early 1970s.

It was sparked by the friendship between a young white schoolteacher, Geoffrey Bardon, and some of the old Aboriginal men who were working in menial jobs at the Papunya settlement. Bardon was deeply impressed by the profound knowledge of these men, as they discussed their territorial land and the stories of its creation, always accompanying their verbal descriptions, with schematic drawings in the sand. He asked a group of the men to paint one of those creation stories on the wall of the Papunya schoolhouse. The excitement within the community generated by this project led to many of the men asking for further materials (initially paint and pieces of wood or Masonite) on which to continue such work. They began to set down their traditional images in paint on board.

Staggered by the creative output, Bardon asked the men if they would like him to take their work to Alice Springs to sell. There, from the Alice Springs General Store, those early board paintings sold for AU$10 to AU$15.

Many of those works are now in museum collections, or sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction.

News of the paintings being done at Papunya spread to other communities across the Central Desert and beyond. Others were keen to attempt something similar.

The movement took hold, representing a huge renaissance of Aboriginal creativity across Australia.

Amekameke – Sacred Place, 1994, by Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Amekameke – Sacred Place, 1994, by Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

4. The names to know

Although the work done in each community stemmed from a shared cultural tradition, individual voices soon became apparent and some artists rose to early prominence.

One of the first Aboriginal artists to achieve international recognition was Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (1932–2002), an Anmatyerre man from Papunya, who created richly worked and finely dotted images in a distinctive pallet of muted desert tones. His works began to be sought out and he exhibited in New York, Paris and London. In 1990 he travelled to London for an exhibition, attended a party at Buckingham Palace and was introduced to Queen Elizabeth II. He later presented her with one of his works, Possum Dreaming.

Rover Thomas Joolama (1926–98), from the Kimberley region of northwest Australia, was another of the early ‘stars’. His bold, almost minimalist paintings, in natural ochres on canvas, were instantly recognisable and appealed to a modernist aesthetic. He was selected, along with fellow Aboriginal Trevor Nickolls (1949–2012), to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1990.

The strong cultural traditions of the Yolngu people in the remote coastal communities of Arnhem Land, northern Australia, have fostered much impressive and beautiful art, among them bark paintings, prints and carvings. Among the foremost artists of the region is Owen Yalandja, from the community at Maningrida. A carver and painter, his distinctive motif is the yawkyawk, a mermaid-like water spirit of the region. His intricately carved and painted representations of these ancestral beings have been exhibited all over the world.

Undoubtedly, though, the work of the most celebrated, and sought after, Aboriginal artist is that of Emily Kame Kngwarreye (1910–96). Aboriginal women did not start painting in their own right, using modern materials, until almost a decade after the men at Papunya. Emily’s introduction to Western art practices came through a batik workshop held for the women at her community of Utopia in the late 1970s.

It was not, however, until she was in her late 70s that she began painting in acrylic on canvas. The results were astonishing. Despite her small stature – she was only a little over five foot – she produced a series of vast, powerful paintings, shimmering with colour. To many Western eyes her loosely worked images suggested the work of the French Impressionists, particularly late-period Monet. Kngwarreye continued to work with undimmed energy and inventiveness throughout her 80s. In 2007, a decade after her death, she became the first Aboriginal artist to have a work sell for over AU$1m at auction. In 2017, at another auction, the same picture, Earth’s Creation I, fetched AU$2,100,00.

In 2025 Kngwarreye will become the first Aboriginal artist to have a solo exhibition at Tate Modern in London. It will also be the first large-scale presentation of her work anywhere in Europe.

Works currently on show in the exhibition We are everything all the time always, a show about place, spirits and objects that connect us with the spiritual dimensions in life (for details see below)

5. Art as evidence

Aboriginal art is not just extraordinarily beautiful and rich in significant meaning (telling the timeless tales of creation), it can also be an important legal resource. Aboriginal paintings have, in recent years, frequently been used as evidence in land rights claims by Indigenous peoples.

When the British laid claim to the Australian continent in the early 19th century they did so by invoking the principle of ‘terra nullius’ – suggesting that the land was essentially unused by existing inhabitants, who thus had no rights to it. In the eyes of the British settlers, the nomadic Aboriginals seemed to have no visible system of land management or agriculture.

Aboriginal culture, however, derived from a very careful and systematised engagement with the land. The story of that engagement – the seasonal nomadic round and the tending of the desert waterhole – is preserved in their stories of the land and its creation.

Today Australian judges and lawyers often travel to remote Aboriginal communities where they are confronted by a giant collaborative painting of the surrounding land. Each artist steps forward to explain the origins of their ‘country’, and tell the story of its creation and its life. On the strength of such pictures – and the knowledge they enshrine – vast tracts of Australia have been returned to Aboriginal ownership.

Janganpa Jukurrpa (Brush-tail Possum Dreaming) – Mawurrji, 2017, by Judith Nungarrayi Martin. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Janganpa Jukurrpa (Brush-tail Possum Dreaming) – Mawurrji, 2017, by Judith Nungarrayi Martin. Image: Courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery

Rebecca’s top tips

See Aboriginal art in the UK

Check for updates on the Emily Kame Kngwarreye exhibition at Tate Modern

The British Museum holds a wealth of Aboriginal art in its collection. A beautiful selection of weavings, bark paintings and canvases can be found on display in the 'Living and Dying' gallery

The Gallery of Modern Art Glasgow, spearheaded by museum director Julian Spalding, was the first public institution in Britain to display Indigenous art alongside Western masterpieces. The museum holds fine examples of Aboriginal paintings and tribal artefacts for public study and enjoyment

Explore the rich history of Aboriginal art in my own gallery, the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery in London. There is a dedicated Aboriginal gallery on the first floor and a museum-quality programme of temporary Aboriginal art exhibitions; the gallery also holds the largest public library of Aboriginal art publications outside of Australia. Don’t miss our current exhibition We are everything all the time always, featuring Aboriginal sculpture reflecting the cycle of life and death, on until 29 February 2024. It includes the largest installation of lorrkon – finely painted log coffins from the Northern Territory of the Australian desert – outside of Australia to date

Recommended reads

Sun & Shadow: Art of the Spinifex People (2023), Editors Jon Carty and Luke Scholes: a captivating story of the expression, community resilience and artistic evolution of the Spinifex people from the central Australian desert

Wally Caruana’s Aboriginal Art (1993): a multifaceted survey of 20th-century Aboriginal visual culture, written by the former senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art at the National Gallery of Australia

Bruce Chatwin's The Songlines (1987): a semi-fictionalised narrative of a journey through the Australian desert. Along the way Chatwin's protagonist encounters and explores the sacred customs of nomadic groups with reverent curiosity

Pat Lowe’s In the Desert: Jimmy Pike as a Boy (2007): the colourful story of one of the foremost Desert Painters, Jimmy Pike, as told by his English-born widow and great champion. This remarkable and intimate account of a traditional Walmajarri boyhood, one of the last of its kind, illuminates the oeuvre of this most significant artist

Adrian Newstead’s The Dealer is the Devil: An Insider's History of the Aboriginal Art Trade (2014): an absorbing personal history of the business of Aboriginal art, as told by one of the Australian market's leading art dealers

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

About the Author

Rebecca Hossack

Born in Melbourne, Rebecca Hossack is director of three internationally renowned galleries – two in London and one in New York. She is credited with introducing Aboriginal art to Europe, and has curated important collections from Papua New Guinea, tribal India and the Bushmen of the Kalahari. The Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery also advocates contemporary Western artists who resist the dominant trends of the modern art world, exploring how arts and crafts can collaborate by showcasing a diverse array of media. Rebecca served as the Australian cultural attaché in London from 1993–97, initiating literary links between Australian and British writers and organising a series of exhibitions of Australian art in London. She has curated exhibitions of Aboriginal and non-Western art both in the UK and worldwide, working closely with multiple museums, including the British Museum and the V&A. She also campaigns to preserve rock art in Western Australia’s Burrup Peninsula. Among her talks for The Arts Society are Rock, bark, ochre: the story of Aboriginal art in the culturally distinct communities of the north of Australia; Crocodiles, cyclones and cave paintings: a history of Aboriginal art; and Dreamtime to machine time: the origins of Aboriginal art in ancient ceremonial designs to the beginnings of the modern Aboriginal art movement at Papunya in the early 1970s, and its subsequent spread across the Indigenous communities of the Western Desert.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition