This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on…the nation’s cathedral treasures

Become an instant expert on…the nation’s cathedral treasures

19 Apr 2023

With eyes soon on Westminster Abbey for the May coronation of King Charles III, we’re reminded once more of the remarkable architecture and history of our key ecclesiastical sites. But what about the treasures they hold? Our expert, Janet Gough, reveals the stories behind five very special artefacts held in cathedrals across England and Wales

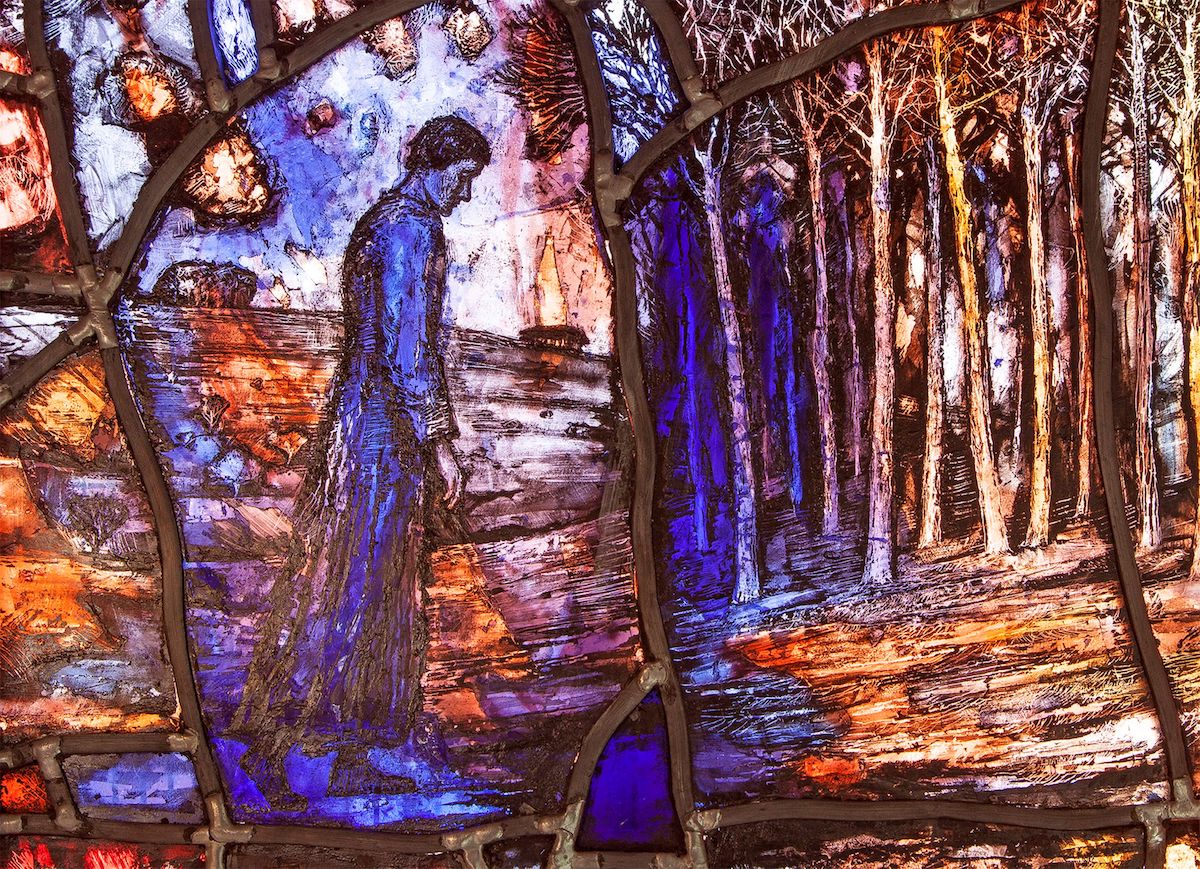

Precious glass: a detail from Thomas Denny’s 2016 Richard III-themed stained-glass windows at Leicester Cathedral

‘Cathedrals aren’t just buildings – they are treasure houses. So why are they overlooked as museums?’

Historian and broadcaster Simon Heffer, The Daily Telegraph, December 2022

Richard III, reburial and redemption: stained-glass windows, made by Thomas Denny in 2016, Leicester Cathedral

Richard III, reburial and redemption: stained-glass windows, made by Thomas Denny in 2016, Leicester Cathedral

1. Lost and found

This extraordinary work of art speaks of the things King Richard III lost and, in doing so, brings an everyman element to his story.

He reigned from 1483 to his death on 22 August 1485 at the Battle of Bosworth. Over 500 years later, in 2012, his remains were famously discovered in a Leicester car park, once the site of a Franciscan friary. Richard was then reburied 50m away in Leicester Cathedral in March 2015. The congregation included both Yorkists and Lancastrians whose ancestors had fought in the battle.

Leicester Cathedral commissioned the painter and stained-glass artist Thomas Denny to design and make two new north-facing windows for the chapel of St Katharine, which sits adjacent to King Richard’s tomb. The windows were installed in 2016, just as Leicester City Football Club won the Premiership, so Denny included a football in his design.

These ‘redemption’ windows explore themes of reconciliation using scenes from the life of the king, in combination with biblical stories. Richard is portrayed not only as someone rooted in the Wars of the Roses (1455–87) but also as an archetype for all people.

The windows are rich in painterly detail and colour – particularly red, gold and blue. They were made using traditional methods, with two layers of glass that Denny then painted and scratched colour away from.

We see Richard as a child, as a confident young man, as battle-clad, then broken following the deaths of both his son Edward (1473–1484) and his wife Anne (1456–1485). Ultimately, he is defeated, slung over the back of a horse on bloody Bosworth Field. All this is shown suffused with the radiant presence of Christ, revealed on the road to Emmaus (in one of His resurrection appearances) and in the encounter with sinners in need of redemption.

Spot the vine leaves and grapes, oak leaves and acorns that decorate the capitals in the Chapter House at Southwell – a work known as ‘The Leaves of Southwell’

Spot the vine leaves and grapes, oak leaves and acorns that decorate the capitals in the Chapter House at Southwell – a work known as ‘The Leaves of Southwell’

2. Sculpted gems

The naturalistically carved ‘Leaves of Southwell’, dating from the 1290s, can be found decorating the Chapter House at Southwell Minster in rural Nottinghamshire. Not only are they beautiful, but there’s evidence they have real appeal for a modern audience. In a recent competition run by The Association of English Cathedrals, seeking the 10 most admired cathedral treasures out of a choice of 50 drawn from my book Deans' Choice: Cathedral Treasures of England and Wales, 4,477 votes out of 5,000 were cast for ‘The Leaves of Southwell’.

These extraordinary deep-cut carved capitals feature 12 different local leaves. ‘Such is the skill of the carving,’ writes the historian Simon Heffer, ‘one might think them the work of Grinling Gibbons 400 years later.’

The architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner wrote his monograph The Leaves of Southwell in 1945, describing in detail the exquisite carvings of animals, leaves and mythical creatures all around the Chapter House. The carvings are a fine example of the English Gothic style and are recognised as being of international significance. The skill, ingenuity and powers of observation of the medieval stonemasons who made them mean ‘The Leaves of Southwell’ are unrivalled in England. We do not know the artist, but it may have been the Meister at Naumburg Cathedral, whose work has recently been awarded World Heritage status and was itself influenced by carving at Reims Cathedral.

A major project of conservation and repair, completed in 2022, has now given us new insights into how and why these superbly decorated stone carvings came to be in this small market town in Nottinghamshire, once home to the Archbishops of York.

Could the splendid octagonal Chapter House reflect nearby Sherwood Forest, where the natural world bursts with vitality? How do the ‘Leaves’ speak to us, seven centuries later, of harmony and fragility in God’s creation, providing insight as we counter climate emergency?

The adjacent Palace Gardens complete the visitor’s experience, with exploratory trails tracing the new planting of all the species found in the Chapter House.

The Brougham Triptych, a masterpiece of Flemish woodcarving, at Carlisle Cathedral

The Brougham Triptych, a masterpiece of Flemish woodcarving, at Carlisle Cathedral

3. Everyday peoples, extraordinary skills

The Brougham Triptych (1515–20) is a carved and painted Flemish oak altarpiece depicting the birth and Passion of Christ in intimate contemporary detail. It stands as the altar reredos in the Chapel of St Wilfred in Carlisle Cathedral.

At the time of the triptych’s making it was the early 16th century in northern Europe, on the cusp of the Reformation. This was an era of heightened religiosity and improved realism. Artists were drawing directly from the world around them – think of Albrecht Dürer’s drawing of a tuft of grass.

The intricately carved oak panels of the Brougham Triptych (meaning an altarpiece in three pieces) are peopled with men and women one would find in the streets of many cities. It is a moving and realistic work. Look at the fellow wearing glasses: what is he doing? And observe the faces moving in that crowd of people.

The outer panels, which would have closed the altarpiece during certain liturgical seasons, have long since been lost, but the remaining sections are outstanding examples of their type. As now configured, the main panels depict the Road to Calvary, the Crucifixion and the Deposition and Lamentation. Beneath the main panels are scenes from the life of Jesus: the Circumcision (for that is what we see in this image), the Presentation in the Temple, the Visit of the Magi and, to the far right, the figure of Jesse.

The vibrancy of the panels is remarkable. I love the detail of those 16th-century glasses on the priest carrying out the circumcision. The face and costume of every figure portrayed is individualised – carved and painted with great skill and with an empathy and imagination that gives the triptych an exceptional communicative power.

The triptych bears the symbol of the Antwerp Guild of Woodcarvers, confirming its place of origin. It is thought to have been in a church in Cologne until it was brought to this country by Henry Brougham (1778–1868) in the 1840s. Brougham was at one time Lord Chancellor of England and also a prominent slavery abolitionist. The triptych was installed in the family church of St Wilfred’s, Brougham, where it was cut into three pieces to fit between the windows. The conditions in the church took their toll, and in the 1970s the triptych was reassembled, restored and displayed for seven years at the Victoria and Albert Museum. It was then installed in Carlisle Cathedral in 1979.

A tiny portable sundial – the Apple Watch of the 900s?

A tiny portable sundial – the Apple Watch of the 900s?

4. Timely survivors

Canterbury Cathedral was founded in 597 by St Augustine who was sent by Pope Gregory the Great to evangelise Anglo-Saxon England and regularise the English church. Canterbury became and remains the seat of one of two Archbishops of the Church of England (the other being York).

During excavations in Canterbury’s Great Cloister in 1938 this pocket-sized sundial, just over 6cm in length, was discovered.

It is a unique survival from Anglo-Saxon times and is made of a tablet of silver, with a cap and chain of gold and a separate gold pin. The cap is decorated with interlacing; its end is formed as the head of a beast and the chain and pin are also finished with beasts’ heads. Two of the heads still have tiny gems for eyes. Abbreviated names of the month in Latin are inscribed in pairs in three lines on the broad faces of the tablet. Around the sides the words‘Health to the maker. Peace to the owner’ are incised in Latin.

The sundial was probably made in the 10th century and is an intricate piece of design. The pin was placed in the hole for the relevant month. When the sundial was suspended from the chain, it used the altitude of the sun to calculate three separate times of the day. The calculations are likely to have been used to indicate times for prayer as part of the seven daily divine offices.

Precious timepieces can be found in other cathedrals. Fast forward to 1390 and Wells Cathedral’s highly technical and beautifully decorated astronomical clock is another great example. Its primary function was to get the vicars choral to the cathedral in time for the increasing number of services. It has a 24-hour dial (who said that was a 20th-century invention?) and another lunar dial and, to cap it all, on the quarter hour knights come out to joust.

A jewel-like painted triptych by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in Llandaff Cathedral

5. A ‘big’ delight

St Deiniol founded his clas or monastic community at Bangor – now Bangor Cathedral – in 525. It is one of at least two of the six Welsh cathedrals that predate the English cathedrals as places of continuous Christian worship. In the neighbouring diocese, St Asaph’s Cathedral has a copy of William Morgan’s first Welsh Bible 1588, authorised by Elizabeth I.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) created his gloriously coloured The Seed of David painted triptych (1856–64) for Llandaff Cathedral, just outside Cardiff. It was one of the Pre-Raphaelite artist’s first major commissions and he was wildly enthusiastic – ‘a big thing which I shall go into with a howl of delight’.

While Rossetti chose as his subject the Nativity of Christ, the title emphasises Christ’s descent from David, who appears on both wings of the triptych: on the left as a shepherd boy and, on the right, as a king.

The centre panel, featuring both a king and a shepherd visiting simultaneously to pay their respects is quite revolutionary for the time. Showing that Christ can be worshipped by both rich and poor, it was a sumptuous statement on social equality. The infant Christ holds out his hand to be kissed by a poor shepherd and his foot by a king, demonstrating the superiority of poverty over wealth.

Janet’s top tips

Visiting cathedrals

All 50 cathedrals of the Church of England and Church in Wales are open daily for worship and visiting. Many visitors enjoy staying for Evensong, a short (often choral) service held in the late afternoon or early evening. All are welcome and it’s free to attend. It’s worth checking cathedral websites for opening hours, services and specific events.

Discover our five treasures

The pieces featured in this ‘Instant Expert’ can be found at:

wellscathedral.org.uk

llandaffcathedral.org.uk

Great reads

Last year I asked the deans of all 50 cathedrals of the Church of England and Church in Wales to select one treasure from their cathedrals to feature in my new book Deans' Choice: Cathedral Treasures of England and Wales (published by Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers). The 50 chosen objects – one from each cathedral from Carlisle to Cardiff to Canterbury – span over 1,300 years, from 672 to 2020. See cpo.org.uk/books/cathedral-treasures-shop.html

Director’s Choice: Cathedrals of the Church of England, by Janet Gough (Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers)

England’s Cathedrals, by Simon Jenkins (Little Brown, 2016)

Europe’s 100 Best Cathedrals, by Simon Jenkins (Viking, 2021)

Heaven on Earth: The Lives and Legacies of the World’s Greatest Cathedrals, by Emma J Wells (Head of Zeus,2022)

The Leaves of Southwell, by Nikolaus Pevsner (1945) – a gem if you can get it

Pillars of the Earth, by Ken Follett (Penguin, 1989) – a gripping novel on the building of a cathedral in the aftermath of the 1130s English Civil War

The Spire, by William Golding (Faber & Faber, 1964), tells the story of one man’s vision – the construction of an enormous spire onto a medieval cathedral (loosely based on Salisbury Cathedral) without foundations

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story

Images: Leicester Richard III windows © Richard Jarvis and Aidan McRae Thomson of Norgrove Studios Ltd; The Leaves of Southwell © Southwell Cathedral Chapter; Brougham Triptych, Carlisle Cathedral © Danny Fowler; Portable sundial Canterbury Cathedral © Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral; Dante Gabriel Rossetti triptych © Peter Smith

About the Author

Canon Janet Gough OBE

Canon Janet Gough OBE is an architectural historian and senior heritage consultant specialising in historic churches. She has written three books on cathedrals and church buildings. For eight years she was the director of cathedrals and church buildings for the Church of England. She worked in the City and for 10 years at Sotheby's, after reading history and history of art at Cambridge. She has been a trustee of the Museum of Fulham Palace, the Churches Conservation Trust, the Friends of the V&A and the Priory of Saint John and is a governor of Haileybury. In 2017 Janet was awarded an OBE for services to heritage and in 2021 she became one of the first lay canons of Bangor Cathedral. Her current lectures for The Arts Society include How to pick a favourite church; Cloisters: remarkable cathedral survivors; and Cathedrals: safe places to do risky things.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition