This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on… The Japanese Garden, East and West

Become an Instant Expert on… The Japanese Garden, East and West

16 Aug 2022

Tensions between opposites and no feng shui – these are what you’ll find in true Japanese gardens, says our expert Amanda Herries. Read on and discover all you need to know about their design and history – and how space must be a positive force

A typical Japanese garden landscape

A typical Japanese garden landscape

The late-15th-century Ginkaku-ji (the Temple of the Silver Pavilion) in Kyoto, which was initially intended as an aristocratic retirement villa and garden

The late-15th-century Ginkaku-ji (the Temple of the Silver Pavilion) in Kyoto, which was initially intended as an aristocratic retirement villa and garden

1. STARTING WITH STONES

Say the words ‘Japanese garden’ and you conjure a vision of green, with rocks, maybe a characteristic stone lantern, a temple roof and raked gravel. The vision might be punctuated with gentle pink cherry blossom, meandering water edged with bold blue iris, or perhaps the fiery colours of autumn maples.

Yet you would be unlikely to see all of this in a single garden view in Japan.

There is as big a range of Japanese garden styles as European, and yet something indefinable makes them ‘Japanese’.

The Sakuteiki (Records of Garden Making) notes, assembled by an aristocrat in the 11th-century Japanese Heian period, is possibly the oldest garden design text in the world. Consisting of history, guidance, folklore and taboo, it connects Japanese garden styles directly with Chinese and Korean antecedents. Its guidelines are still used as the basis in garden design today, and pivotal to its message is the importance of the placement of stones in any garden – a method described as 'Ishi wo taten koto’ – the act of setting stones upright.

Chinese garden landscape design includes geomantic rules governing the location of buildings, water, rocks and plantings within a garden. None of this is found in a Japanese garden; there is no feng shui. However, the tension between the opposite – but complementary – forces of in and yo (Chinese yin and yang) will always be present in Japanese design. This creates an asymmetry essential to a successful garden landscape.

Combined with this device is a deep consciousness of the seasons, the impermanence of life and the importance of harmony with nature. But control is always present, in the form of pruning and maintenance, even in the most artlessly ‘natural’-looking garden.

The use of shakkei (borrowed scenery) is a further – and characteristic – trick of Japanese design, deliberately drawing in elements (a tree in the distance, a mountain, forest or building) from outside a designed garden space to augment the view or give the illusion of an extended space. And yohaku (emptiness), a technique derived from China and much used in both Chinese and Japanese painting, renders a white space or void a positive force – not only in art but in a garden.

Ryōan-ji kare san sui garden, Kyoto, which dates to the 15th century

Ryōan-ji kare san sui garden, Kyoto, which dates to the 15th century

2. ALL ABOUT STYLES

The Sakuteiki makes reference to Buddhist doctrines, coming to Japan from India via China, which had been overlaying the indigenous Shinto way of life from the 6th century. It’s also the product of a time when the rich built lavish houses surrounded by magnificent pleasure gardens for strolling, boating and engaging in the arts of dance, music and poetry. For centuries gardens were also created as an expression of ‘paradise’ on earth, in the quest for Buddhist enlightenment.

Subsequent waves of Buddhist teachings included the Zen school, introduced from China and well established in Japan by the 12th century.

Zen places great emphasis on the benefits of meditation for awakening the inner nature and all-important wisdom. It’s no surprise, then, that many of the great Buddhist monastery complexes in the old Japanese capital of Kyoto are surrounded by gardens.

These are not gardens to stroll in but to look upon – and meditate. Composed mostly of rocks and (usually) white gravel, they are high-maintenance, with a history stretching to the 8th century, and Shinto use of white sand or gravel around temples to symbolise purity.

Raking the gravel is also a meditative process in these kare san sui (literally ‘dry landscape’) gardens, which have come to represent both the essence of Zen and a quintessential Japanese garden style.

Crucial to the kare san sui garden is the interaction of the viewer with the garden – not so much an engagement of the senses, as of the mind.

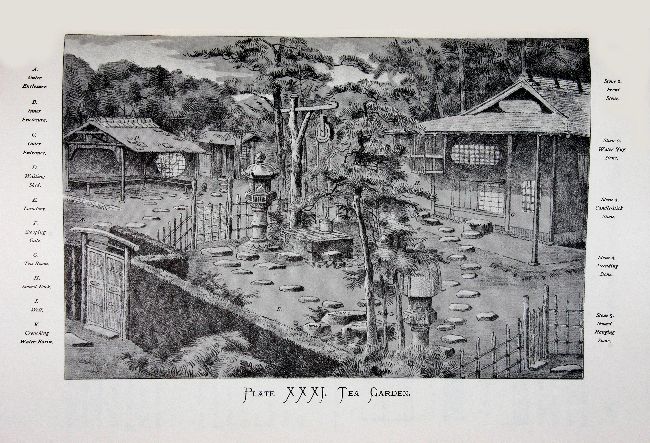

This is the case, too, with the garden style created with the specific intention of preparing the person approaching the tea house for chado – the tea ceremony associated with Buddhism that was highly refined by the 16th century. A small garden, usually entered through a gate in a low bamboo fence – representing a break between worldly turbulence and tranquillity – leads to the doorway of the tea house. It has a rustic, cool feel, with stepping stones set in bare beaten earth, artfully positioned rocks, moss and minimal planting. Walking along the roji niwa (the dewy path) provides a transition – focused on cha no yu (hot water for tea).

A 17th-century Imari porcelain charger, illustrating chrysanthemums and other flowers

A 17th-century Imari porcelain charger, illustrating chrysanthemums and other flowers

3. CONTACT WITH THE WEST

The 16th century was an age of global seafaring and exploration.

European seafarers found their way to the Orient, returning with tales of wonder and, increasingly, exotic goods and materials including silks, painted screens, lacquer wares and porcelain.

Painted screens and, increasingly, porcelain from the great kiln sites at Arita in southern Japan (shipped from the port of Imari), often decorated with scenes of nature and flora, introduced westerners to mysterious trees and flowers they had no knowledge of.

From the 17th century three European ‘physicians’ – men of wide scientific learning – employed by the Dutch East India Company, wrote extensively about this strange land. They were posted on tours of duty at the segregated Dutch trading post of Deshima outside Nagasaki, in a country isolated from the world (with the exception of China and what we now know as the Netherlands) by imperial edict from 1637, through suspicion of foreign influence and religious proselytisation. As keen amateur botanists they gathered specimens and made detailed records of the flora.

Despite fear of discovery and death, Engelbert Kaempfer, Carl Pher Thunberg and Philipp Franz von Siebold collected information that made westerners aware for the first time of hundreds of plants, including cherries, irises, chrysanthemums, lilies and peonies. They also gave their names to dozens of plants familiar in gardens the world over.

Japan remained in its self-imposed isolation until 1854, when American commodore Matthew Perry sailed his ‘black ships’ – unfamiliar steamships belching black coal smoke – into Kurihama harbour near Yokohama, demanding consular relations and the opening up of Japan to foreign trade.

Illustration showing the elements of a tea garden from Landscape Gardening in Japan by Josiah Conder, published in Tokyo in 1893

Illustration showing the elements of a tea garden from Landscape Gardening in Japan by Josiah Conder, published in Tokyo in 1893

4. THE PLANT HUNTERS AND TRADE

Japan – and all things Japanese – became the rage in Europe and America.

Plant hunters, having had tantalising glimpses of Japanese plants and gardens, were among the first to arrive in Japan, travelling throughout the country collecting plants and seeds. Specimens came back to Europe on sea journeys of several months, with many, miraculously, surviving, even if, sometimes, they were muddled up en route.

Bitter rivals John Gould Veitch and Robert Fortune – two giants in the history of plant-hunting (the latter discovering in China, for the British, exactly how tea was cultivated and processed) – chased each other up and down Japan and put their specimens on the same boat home, with confused results.

Interest was two-way, with the Japanese inviting British architect Josiah Conder to Tokyo as an academic and adviser in 1877. Completely captivated by Japanese arts and culture, Conder wrote extensively for English and American enthusiasts, remaining in Japan until his death in 1920. His richly illustrated Landscape Gardening in Japan, published in 1893, has become the seminal work describing gardens and identifying styles and components.

Japanese nurseries were quick to recognise export opportunities. The Yokohama Nursery Company, founded in 1891 and still operating, produced a series of gorgeously illustrated catalogues. They offered irises, peonies and lilies, and objects including bronze cranes and the ubiquitous Japanese stone lantern (with no Chinese or Korean equivalent), for shipment to Europe and America. By the turn of the 20th century lily bulbs in their millions were shipped west.

Diplomats brought back objects (Louis Greville returned home to Heale House in Somerset with a whole thatched tea house, curved bridge and enormous stone lantern, all still in situ) and spread the word about exotic landscapes and plants.

Popular trade exhibitions of the turn of the 20th century also brought Japanese garden style to the masses.

The Japanese Garden at Cowden in Clackmannanshire, called Sha Raku En (the place of pleasure and delight)

The Japanese Garden at Cowden in Clackmannanshire, called Sha Raku En (the place of pleasure and delight)

5. THE JAPANESE GARDEN IN THE WEST

‘How beautiful – we have nothing like this in Japan!’ exclaimed a Japanese dignitary on visiting a ‘Japanese garden’ in England, in around 1906.

International trade expositions attracting large crowds retained popularity into the early years of the 20th century. In America ‘Japanese Village’ exhibits regularly included a Japanese garden. Many of these have survived and can be seen in botanic gardens in San Francisco, Brooklyn, Chicago, St Louis and elsewhere.

Surviving Japanese gardens from the turn of the 19 and 20th century in the West include a delightful – and fragile – garden in the Hague at Clingendael, open for a few weeks a year, and at Tully in County Kildare, the home of the Irish National Stud.

In England the Japan-British Exhibition of 1910 at London’s White City included two Japanese gardens: ‘The Garden of Floating Islands’ and ‘The Garden of Peace’. (The latter was partly saved, moved to Hammersmith Park and restored with some success in 2010.) Five hundred Japanese gardeners came to London together with ornaments, stones and much else to create the gardens for the exhibition. As in America, many stayed on to respond to demand for private commissions. These included the well-known gardens at Tatton Park in Cheshire, substantially and successfully restored from 2001.

The wood-shingled entrance gate to the White City exhibition (modelled on a temple gate in Kyoto) was later moved to Kew Gardens, and augmented by a kare san sui garden in 1996. In 1992 a new landscape was created in Holland Park, close to the remains of an earlier garden.

From the early 20th century dozens of ‘Japanese corners’ were added to private residences throughout the UK but with little understanding of the underlying principles. Japanese ‘styled’ gardens were promoted by nursery companies and regularly at flower shows, particularly Chelsea, from the 1930s.

An extraordinary example was created in a Scottish valley in Perthshire, at Cowden (shown above), from the 1920s, by an intrepid lady traveller, Ella Christie, and a Japanese gardener who tended it until his death. Vandalised in the 1960s, it is being lovingly restored by a descendant of Christie's family.

Other early gardens have not fared so well, but you can now buy any number of plants originating from Japan in any nursery, and a great number of ‘Japanese style’ ornaments to complement them. Are the subsequent gardens ‘Japanese’, or do they just speak, as suggested by a commentator in 1951, ‘with a Japanese voice’?

AMANDA'S TOP TIPS

Places to visit

If at all possible, visit Japan. See the historic gardens in and around Kyoto: the best time to do so is in May (avoiding the first week when public holidays bring crowds) and again in the month of October. You’ll need at least two weeks for these visits.

Among places to visit Japanese gardens in the UK are:

- Tatton Park in Cheshire – an interesting and ‘authentic’ Japanese garden of its time

- Kew Gardens and Holland Park in London have beautiful Japanese garden areas

- The garden valley at Cowden in Clackmannanshire, 15 miles from Stirling, is a fascinating restoration project

- Compton Acres, near Poole in Dorset, laid out in the 1920s, includes a Japanese garden among its other ‘gardens from the world’ (a popular theme at the time)

Find out more

Join the Japanese Garden Society

Good reads

- Sakuteiki: Visions of the Japanese Garden: A Modern Translation of Japan’s Gardening Classic by Jiro Takei and Marc P Keane

- Landscape Gardening in Japan (and supplement) by Josiah Conder and K Ogawa

- The Gardens of Japan by Teiji Itoh, 1998

- Japanese Gardens in Britain by Amanda Herries, 2001 (Shire Publications)

And to help you create a Japanese garden:

- Creating Japanese Gardens by Philip Cave (Aurum Press)

-

Japanese Gardens in a Weekend by Robert Ketchell (Hamlyn)

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT EMAIL...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

About the Author

Amanda Herries

With a degree in archaeology, Amanda was a curator at the Museum of London for a decade, specialising in the 18th to 20th centuries. She spent eight years in Japan studying East-West connections, and draws on this eclectic background for her lectures, writing and broadcasting. Decorative arts, including jewellery, porcelain, dolls' houses and more, combined with social history, inform her studies. Her lectures for The Arts Society include Skin Deep – the beastly art of beauty (18th-century caricatures), The Story of the Willow Pattern, Opium – Seduction, Greed, Art and Japanese Gardens – East and West.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition