This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on…the healing power of plants

Become an instant expert on…the healing power of plants

15 Aug 2023

Whether visiting gardens or sitting within your own, many of the beautiful plants you’ll see represent nature’s medicine box. Their properties are harnessed to create medicines as far-ranging as analgesics and antibiotics. Our expert, Timothy Walker, reveals why plants as diverse as the foxglove and rosy periwinkle can, for many, prove to be a life-saver

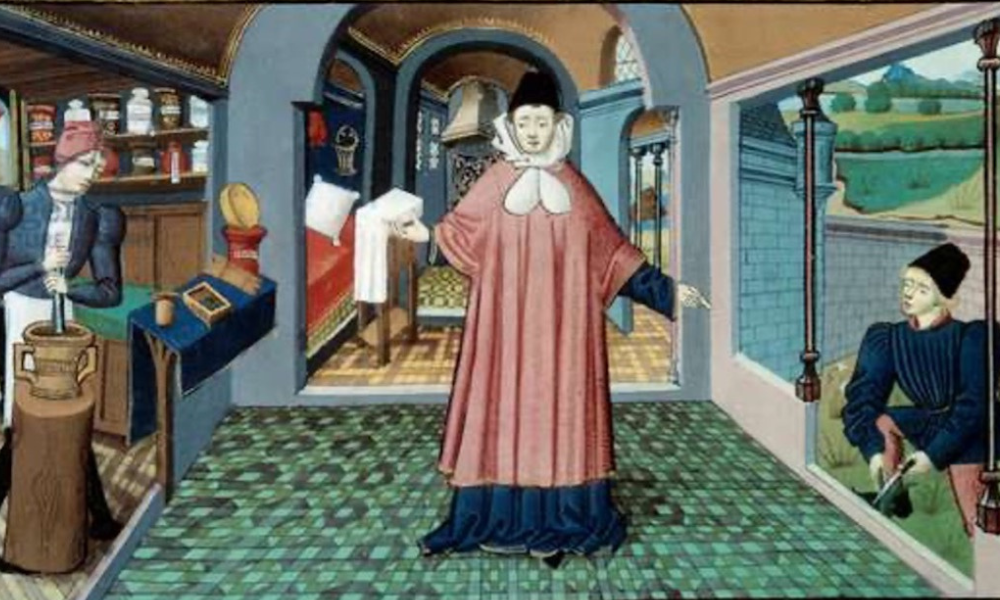

Miniature taken from ‘L'antidotaire 'by Bernard de Gordon (ms. lat. 6966 fol. 154 v.), 1461. Paris, BN / Photo: © Josse / Bridgeman Images. Throughout time humans have honed the art of using plants for medicine; this miniature, by an unknown 15th century artist, is titled ‘Pharmacy: an apothecary, the picking of plants and the preparation of medicaments’, 1461

Miniature taken from ‘L'antidotaire 'by Bernard de Gordon (ms. lat. 6966 fol. 154 v.), 1461. Paris, BN / Photo: © Josse / Bridgeman Images. Throughout time humans have honed the art of using plants for medicine; this miniature, by an unknown 15th century artist, is titled ‘Pharmacy: an apothecary, the picking of plants and the preparation of medicaments’, 1461

Plant or potential curative? A close-up of the white wood anemone

Plant or potential curative? A close-up of the white wood anemone

1. Plants and their superpowers

Mention the role of plants in medicine and people commonly think of herbalism, 17th-century potions and maybe traditional Chinese medicine.

We know our ancestors used the native primrose (Primula vulgaris) to heal wounds, the roots of valerian (Valeriana officinalis) as a sedative, and the dandelion (Taraxacum) for its diuretic properties. The gel in the leaves of the Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis miller) has famously soothed sore skin, while lavender (Lavandula) has long been valued for its antiseptic properties. Species such as the sea pink (Armeria Maritima) and wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) have even been used to treat diseases such as tuberculosis and leprosy.

What is less well known is that more than 110 new chemotherapies approved since 1981 have been derived from, or inspired by nature. Among myriad plants currently used in chemotherapy are the African cherry (Prunus africana), plum yew (Cephalotaxus harringtonia), American mandrake (Podophyllum peltatum) and the European yew (Taxus baccata).

The above just proves that plants are as vital to humans in healing today as they have been for centuries. But when, and more to the point why did our ancestors start using plants, and perhaps fungi, for purposes other than nutrition?

Read on to discover more…

Beautiful and useful: the echinacea

Beautiful and useful: the echinacea

2. Potent pollen and pain relief

The earliest evidence of our ancestors consuming plants with chemicals within them, the kind that would have made them unpalatable, is found in the teeth of Neanderthal skulls. Preserved in the enamel is the type of plant components that taste bitter.

More convincing evidence comes from the caves inhabited by our ancestors. Among the debris found in these early dwellings are bones from the animals they ate, and pollen grains from the plants they used.

Pollen grains are covered in a miracle of evolution called sporopollenin. This astonishing material is borderline indestructible, remaining in perfect condition for millennia. The patterns made by the sporopollenin are often species-specific, enabling archaeologists and anthropologists to make well-informed guesses on which plants once entered these dwellings. In some sites up to 95% of the pollen found in these places derive from plants still used by local people in the regions.

How our ancestors discovered that plants could ease pain and other ailments may have been simply by good fortune or trial and error. What we do know is they could have learnt from observing the plants animals and even insects ate, because we know animals self-medicate. From primates to ants, the antibiotic properties of plants are utilised. We have linked horses chewing willow bark with pain relief. Sightings of mongoose eating echinacea after a fight have been reported. It is proposed that in doing so the mongoose exploits the widely held belief that echinacea can increase the body’s resistance to infection.

A steadying influence: the Ammi visnaga plant / Image: Timothy Walker

3. To the heart of the matter

Certificated first aiders are permitted to keep just one approved drug in their first aid bag: a singular 300mg tablet of aspirin. This is only to be used in the event of a suspected heart-attack. It was the first thing given to my mother when the paramedics arrived following her suspected heart failure. It helps to keep the blood a bit more ‘runny’ and thus easier for the heart to push the fluid around the body. The diagnosis was atrial fibrillation. The first medication used in the hospital was amiodarone, extracted from Ammi visnaga, a pretty garden plant in the carrot family that, as a medicinal herb, has been used for centuries for conditions as diverse as urinary stones and asthma.

Perhaps the best-known heart medicine derived from plants and used today is digoxin, which has the astonishing ability to make a dysfunctional heart beat at the correct pace and strength. Digoxin is harvested from the woolly or Grecian foxglove Digitalis lanata, although originally the chemically similar digitoxin was extracted from the English foxglove, Digitalis purpurea.

The credit for the discovery of this vital plant-based drug is attributed to the Shropshire-born Dr William Withering (1741-1799). His work was prompted by reports of a Shropshire family using an infusion of a cocktail of plants to solve a range of maladies. It was Withering who took apart the mixture and investigated its components.

Although something of a wonder plant, the foxglove comes, as do many medicinal plants, with a caveat. They are known to be toxic. This should not surprise us as there is a warning on the side of every box of tablets urging us not to exceed the stated dose. It may be that these toxic compounds are produced by the plants as a defence against grazing animals. The medical exploitation, using a smaller dose, is just serendipity.

Sweet wormwood, a plant long favoured in China to treat high temperatures

4. Soothing the fever

Each year hundreds of thousands of people die from malaria and hundreds of millions are affected by the disease.

In the 17th century Jesuit missionaries came across a treatment for malaria, which was being used by the indigenous people of South America. The drug quinine, extracted from the bark of the cinchona tree, Cinchona officinalis, was taken back to Rome where malaria was still endemic. The miracle property of the quinine led to the christening of the plant as ‘Jesuit’s bark’, though the bark and knowledge was not theirs.

But that wasn’t the end of the story.

The unicellular organism that causes malaria, Plasmodium falciparum, unfortunately adapted and was able to resist the effects of the quinine. As a result, various synthetics were used, but it was ultimately to be plant-based traditional Chinese medicine that provided an alternative.

Sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua) has been used in China for centuries to treat fever – and that fever was malaria.

But there were hurdles to the world adopting the sweet wormwood as a panacea. For example, before a drug can be licensed in the UK, the manufacturer must satisfy three criteria. The medicine must be efficacious and safe and be prescribed at a precise dose. To fulfil the last requirement, the active ingredient must be identified because from this is calculated the molecular weight. It is not acceptable for your GP to prescribe a handful of leaves in a mug of hot water, even if it works and is safe.

Bringing this story to the 1970s, it was eventually Professor Tu Youyou, a Chinese pharmaceutical chemist, who successfully isolated and identified the active ingredient. It was named Artemisinin.

Since then it has been calculated that this drug has saved well over one million lives.

In 2015 Professor Tu Youyou became the first female Chinese citizen to be a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Medicine for her work on this. She shared the prize with William C. Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura for their discoveries for therapy against infections caused by roundworms – together the three revolutionised therapy for patients suffering from cruel parasitic diseases.

Healing powers: the modest looking rosy periwinkle (Catharanthus roseus) / Image Timothy Walker

5. Yew leaves and rosy periwinkles

As mentioned at the start, myriad plants play a key role in the field of cancer treatment. For example, American mayapple (Podophyllum peltatum) is the source of several chemotherapies, including etoposide, derived from the podophyllotoxinof this plant. Etoposide is used in the treatment of testicular and other cancers. In recent years it has also been involved in the treatment of the condition known as a cytokine storm (when excessive or uncontrolled levels of cytokines are released, resulting in hyper-inflammation), as experienced by some Covid-19 patients.

In the 1970s and 1980s the leaves of the European yew (Taxus baccata) were the only sustainable source of the raw material for the production of docetaxel (sometimes known by its brand name taxotere), which first rose to recognition as a treatment for breast cancer. The possibility of using yew trees to treat cancer was first discovered in the USA in the 1960s. However, the plant extracts used then were found in the bark of the trees. In order to treat one patient, you needed to remove the bark from three mature yew trees to harvest sufficient quantities of the drug. This was never going to be a sustainable supply, so the discovery of an alternative in the leaves of the European yew trees was a major breakthrough, because now it could be produced in commercial quantities.

When I worked at Oxford Botanic Garden, I occasionally took groups of school children on tours of the plant collections. All my tours included the rosy periwinkle Catharanthus roseus. This unassuming plant with pink flowers produces two highly toxic and complicated molecules: vincristine and vinblastine. The former is used to treat a form of childhood leukaemia. Since its discovery it has saved the lives of 80% of children born with this type of leukaemia. To quote one paediatric oncologist I know ‘this was a game changer’. One of the eight-year-old school children on a tour I was leading knew the name of the plant, what it is used for and what the chemical is called. He knew this because it had saved his life.

Timothy’s top tips

First a caveat: the use of the plants mentioned above must be left in the hands of trained physicians. Self-medication is dangerous with these highly toxic plants.

Great reads

One of the best places to start learning more about the use of plants in medicine is to get a copy of Nature’s Medicine: Plants That Heal – A Chronicle of Mankind’s Search for Healing Plants Through the Ages by Joel L Swerdlow.

For more information about medicinal plants see Plants for People by ethnobotanist Anna Lewington.

Visit

Many gardens in the UK have a heritage of herbal medicine and are open to visitors. Among them are:

The Chelsea Physic Garden, London, established in 1673, marking its 350th anniversary this year.

Dilston Physic Garden, Corbridge, Northumberland, established in the early 1990s and known for its research on plants that can improve memory, attention and focus.

University of Bristol Botanic Garden, home to the largest collection of traditional Chinese medicinal herbs in the UK.

The Garden of Medicinal Plants at London’s Royal College of Physicians (RCP) contains 1,100 plants with links to medicine. Senior physicians of the RCP give tours of the garden on the first Wednesday of the month at 2pm (April–October); booking is essential.

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

About the Author

Timothy Walker

was Director (Horti Praefectus) at the Oxford Botanic Garden and Harcourt Arboretum for 26 years. During this time the garden won a gold medal at the Chelsea Flower Show for an exhibit of modern medicinal plants. Since 2014 he has been a lecturer and tutor in Plant Science at Somerville College, Oxford. His Arts Society lectures cover the history of gardening, the convergent evolution of fine art and garden design, botanical illustration and the healing power of plants. Among them are Beauty in truth: the past, present and future of botanical illustration; Garden hunting in China and The healing power of plants – why plant derived treatments are not an alternative, but the real thing.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition