This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on…the art of the table

Become an instant expert on…the art of the table

19 Dec 2023

Artists have always had a fascination for scenes of food and feasting. As the holiday season of gatherings is here,our expert, Nicole Mezey, invites you to feast your eyes on some of the best – and most bizarre – examples of artworks that celebrate dining

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster dines in style with the King of Portugal, from the Chronique d’Angleterre(Volume III), late 15th century. Image: Wikipedia

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster dines in style with the King of Portugal, from the Chronique d’Angleterre(Volume III), late 15th century. Image: Wikipedia

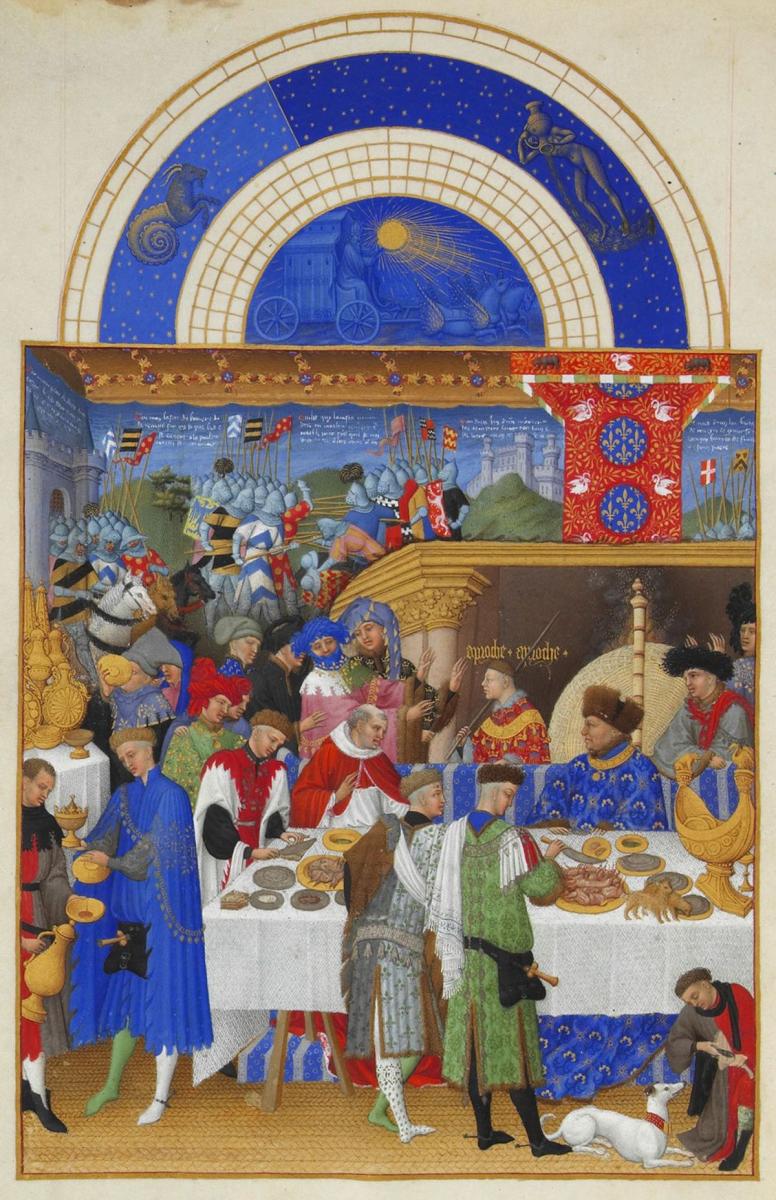

January, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1413–16, ink on vellum, by the Limbourg brothers. Image: Musée Condé, Chantilly

January, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1413–16, ink on vellum, by the Limbourg brothers. Image: Musée Condé, Chantilly

1. Salty standing

In Western society, eating has always been a public, shared activity.

For the poor this was through necessity; for the wealthy, as the finest opportunity to display wealth and status.

Shown here is the Epiphany feast of one of the great collectors of the 15th century, Jean, Duc de Berry. We see a scene set in a sumptuous, tapestried interior filled with people who, apart from the Duke himself, are respectfully standing rather than sitting.

Even in such magnificence, though, the table itself is merely a moveable trestle, disguised by a cloth. There is nothing that could be described as a table setting. The plates for all are scattered and the only implements are curved knives to carve the meat. The opulence is in the serving dishes – the huge, shimmering golden pots and dishes shown not on the table but, as here, arranged on a side buffet. The only exception to this is the golden boat on the dining table; it is a salt cellar, in this case one we know from the Duke’s inventory to have actually existed.

Salt was expensive, not because it was rare in itself but because of the difficulties in refining it, and also because it was used in rituals of the Catholic Church as a symbol of purity. At table, therefore, the salt cellar was placed by the guest of honour, not just to facilitate seasoning but as the emblem of social standing. Such vessels (of which several survive) are conspicuous, identifiable emblems of luxury, but the significance of our next item is less obvious to us.

A 15th-century silver and gilt table fork from southern Germany. Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A 15th-century silver and gilt table fork from southern Germany. Image: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

2. It’s all about the fork

Utensils took a long time to evolve from the age of the Duc de Berry, but in time there was an item that would revolutionise both eating and table manners.

It was the fork.

Made only in the most expensive and durable materials, like this gilded silver example, it was destined to remain, as a result, the prerogative of the elite.

Introduced to Venice by a Byzantine princess in the 11th century, forks remained an arcane personal accessory. Nor was this innovation without controversy for, as one cleric thundered: ‘God in his wisdom has provided man with natural forks – his fingers. Therefore it is an insult to Him to substitute artificial metallic forks for them when eating.’

It took time for the fork to be regarded with less suspicion. Only in the 15th century, as refined sugar became more available, and with it a taste for fruits in syrup, did the fork come to the fore. Without one, fingers became sticky, and the fruit slipped off spoons. The tines of a fork, however, were ideal for spearing fruit. As a result this new utensil rapidly became a fashionable accessory.

The fork brings with it notions of delicacy around food, of finesse, and the associated refinement of table manners. It continued, however, to be regarded with suspicion by many. The first president of the United States of America, George Washington, who owned one, was accused not only of affectation but of ‘abandoning the ways of democracy’.

The Wedding Feast by Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Image: Wikipedia Commons

The Wedding Feast by Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Image: Wikipedia Commons

3. Feasting in the frame

While the salt cellar and fork were associated with privilege, the opportunity of food in quality and quantity was even more important for the poor.

Seen here, in Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s The Wedding Feast (sometimes known as The Peasant Wedding Feast) we see not a tapestried hall but a barn filled with hay. The food is carried in on a door taken off its hinges, and the food is bread and soup, or porridge.

Here there are no forks, nor the luxury of meat.

Around the bride the guests indulge themselves – a non-idealised, often witty observation in the near-caricature of certain figures. See the child in the foreground in a borrowed hat, licking out a bowl. One of the porters has a spoon tucked in his hat: a subtle reminder of the contemporary experience of famine in the Low Countries. People carried spoons so to profit immediately from any available opportunity to eat.

What we respond to in this painting is not just form but mood and tone. There is a sense of energy and even babble. We see the way in which food creates a community around the table, and the rarity for this group of such an opportunity to feast to the full.

Significantly, Brueghel presents the way such an occasion can define those both inside and outside the social circle – as suggested in the yearning hunger of the piper on the left, present but excluded from the feast.

Emperor Rudolf II as Vertumnus, 1591, by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Image: Skoloster Castle, Sweden/Google Art Project

Emperor Rudolf II as Vertumnus, 1591, by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Image: Skoloster Castle, Sweden/Google Art Project

4. The veggie option

If the experience and rituals of eating provide pleasure and display across the classes, food itself, and our relationship with it, inevitably also become a major artistic theme.

One of the most bizarre examples of this occurs in the 16th century, in the art of Italian artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who worked in Vienna and Prague for the Holy Roman Emperors. His composite paintings, in which subjects are constructed as jewel-like mosaics of fruits and vegetables, are both extraordinary and unique, balancing the fascinating and the grotesque.

Here Arcimboldo recreates a real individual – Emperor Rudolf II himself – as Vertumnus, Roman god of the seasons, who seduced Pomona, goddess of fruits and orchards. It is a deliberately arcane reference, conceived for an elite and educated audience.

The portrait is built of the produce of all seasons, in a sort of animated still life. Summer fruits create a crown of pomegranates, plums and cherries; the head itself includes autumnal apples and chestnuts. The body is the winter harvest of cabbage, leek and onions, while around the neck is draped a garland of the flowers of spring. We not only have four seasons but also geographical reach as, with corn from the Americas, Arcimboldo pointedly illustrates his patron’s power not only over nature but the known world.

Contemporaries referred to Arcimboldo's portraits as scherzi (jokes), but they also reflect an age, and a court, discovering the serious investigation of nature. It comes as no surprise to learn that these works were rediscovered by the Surrealists, who adored them for their fantasy and double meaning.

Judy Chicago, "The Dinner Party," Brooklyn Museum. Credit: David Grossman / Alamy Stock Photo

Judy Chicago, "The Dinner Party," Brooklyn Museum. Credit: David Grossman / Alamy Stock Photo

5. A seat at the table

Our last work is one of the great think pieces of the late 20th century – nominally by the American artist Judy Chicago but (and this is something that she would not only acknowledge but celebrate) executed by a team of women working together to realise a core vision that was hers, and to which each contributed not only skills but also creativity.

It is a work using food and the experience of eating to correct women’s historical invisibility – ‘to give credit to the preparers of feasts, the setters of the tables, the makers of the tablecloths…’. The last is particularly ironic. The tablecloth was of Swiss linen, the first version of which was shrunk by industrial pressing so, in the end, all 2,000 feet of it had to be dampened and ironed by hand.

This multimedia installation is a triangle, each side bearing 13 place settings of plates and runners representing remarkable individual women over millennia. The cohesion comes from the common elements: the runner represents the social context and the plate the individual. As you circumnavigate the table, the butterfly form of the plates surges up, symbolising women's increased strides towards liberation.

The apotheosis is in the final setting of all (nearest on our left in this image) devoted to Georgia O’Keeffe, the first woman artist to have a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Here the runner is simple, but the plate, its colours reflecting those of O’Keeffe’s work, entirely dominates, and the butterfly shape rises high and free.

Nicole’s top tips

Great reads

Silver by Philippa Glanville, V&A Museum (2003), a social history of silver

Food and Feasting in Art by Silvia Malaguzzi, Getty Guide to Imagery (2008), exploring the rituals and symbolism of dining

Food in Art: From Prehistory to the Renaissance by Gillian Riley, Reaktion Books (2014), on how works of art provide us with tales of the gathering, preparation and preservation of food in history

Discover more stories online

Sample a revealing tour of arts and objects connected to food in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Dip into the history of tableware and settings

Get a taster of more about food and drink in the rich period of European painting of 1400–1800

Find out more about Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

About the Author

Nicole Mezey

is an art historian and fellow of Advance HE and the Royal Society of Arts. After 30 years as senior lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast, she now lives in London and lectures for organisations including the Institut Français, National Museums, The Course and The Arts Society. In addition to talks on aspects of her specialist area, the Middle Ages, she also explores a range of subjects in lectures including Feasts and fantasy, The Corsican adventurer: images of Napoleon, The end of shadows: light and the painter and Smoke, mirrors and sanctity: Tudor patronage and art as propaganda.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition