This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on… …the magical world of the herbarium

Become an Instant Expert on… …the magical world of the herbarium

15 Nov 2022

Royal Botanic Gardens Kew call them ‘a cross between a museum of priceless artefacts and a warehouse of birth certificates for plants’ – welcome to the fascinating world of herbariums. Our expert Mark Spencer reveals their history and links to art

Not just any old pressed flower: this Alchemilla is a precious herbarium specimen, pressed by philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-78); it is in the Bibliotheque du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris

Not just any old pressed flower: this Alchemilla is a precious herbarium specimen, pressed by philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-78); it is in the Bibliotheque du Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris

1. What is a herbarium?

Our planet is a beautiful place and much of that beauty is created by plants. They are the multi-hued green drape that adorns Gaia.

Plants are also one of the most diverse groups of organisms on the planet, with an estimated 321,000 species of wild plants and hundreds of thousands of cultivated plants, the latter known as ‘cultivars’ (cultivated varieties).

Botanists and horticulturists have multiple ways to understand such huge diversity – and a particularly important tool is the herbarium.

Herbariums are dried collections of pressed plant specimens. They are rather like plant libraries, being a repository of information, cataloguing where plants come from and who they were collected by. Each specimen is a unique and valuable item of scientific and cultural history.

It is thought that, in the near 3,000 herbaria found around the world, there are over 380 million plant specimens. Such vast collections, often stored in natural history museums or botanic gardens such as Kew are expensive to make and even more costly to maintain – so why do we do collect plant specimens?

One important reason is they are valuable tools in the naming of plants…

The Bellis perennis, better known as the common daisy

The Bellis perennis, better known as the common daisy

2. What’s in a name?

A well curated herbarium is a unique source of information and a gateway to understanding plant diversity. But a key step in understanding that diversity is appreciating the ingenuity of the scientific names (known as binomials) we give to them.

Those names tell us so much about them.

The rules governing the naming process is known as nomenclature. The science that defines and describes biodiversity is taxonomy. Both nomenclature and taxonomy rely upon herbarium specimens.

The use of the binomial was formalised by the 18th-century Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778).

In two series of great scientific works, Species Plantarum (the first edition of which was published in 1753) and Systema Naturae (1758) Linnaeus established the practice of giving each different organism a generic (singular:genus, plural: genera) name and a specific epithet (the species).

We humans, for example, are Homo sapiens: the ‘Homo’ being the genus and ‘sapiens’ the species.

Similarly, the common daisy of our lawns is Bellis perennis. It is one of 14 species of recognised members of the genus Bellis. Plant names convey some meaning about the plant and in this case Bellis means ‘pretty’ or ‘beautiful’, while perennis means ‘perennial’. Clues lie in all naming: other members of the Bellis genus are named, for example, annua (annual), azorica (from the Azores), prostrata (growing flat or prostrate) and rotundifolia (round-leaved).

Beware, here comes the tricky part.

On their own, and without being attached to an object and a written description of the plant, scientific names have no meaning or ‘substance’.

By this I mean the scientific name is the means of unlocking the concept of the species – it is an aide memoir. To give a scientific plant name ‘substance’, botanists link the name, through scientific publications and a ‘designated’ herbarium specimen.

Herbarium specimens that have been ‘designated’ in this manner are called ‘type specimens' – they are the core of our understanding of plant diversity. Globally, there are hundreds of thousands of type specimens representing botanists’ scientific ideas and discoveries.

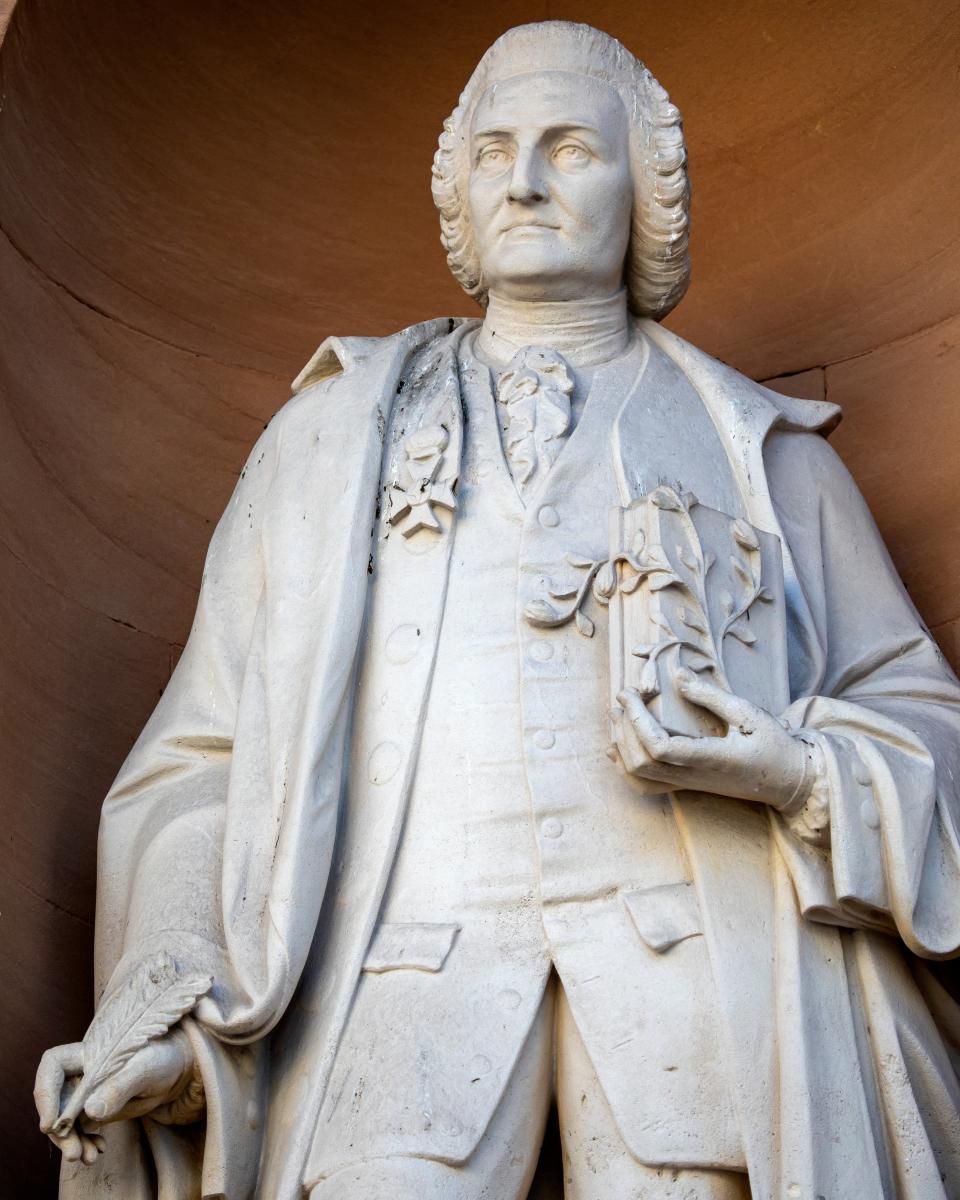

The statue of Carl Linnaeus, famous for his work in the science of identifying, classifying and naming organisms, at Burlington House, Piccadilly

The statue of Carl Linnaeus, famous for his work in the science of identifying, classifying and naming organisms, at Burlington House, Piccadilly

3. A society – and the earliest herbaria

Inside the front archway of Burlington House on Piccadilly in London, there is an easily overlooked entrance. This leads to the Linnaean Society of London, founded in 1788 in Linnaeus’s honour by Sir James Edward Smith (1759 –1828).

The society is the world’s longest surviving organisation dedicated to the study and dissemination of knowledge of natural history, evolution and taxonomy. It is famous for being the institution where the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace was first presented.

Inside these august, yet friendly (pay us a visit), walls there is a vault. Within that vault, there are thousands of carefully preserved plant specimens that are part of Linnaeus’s immensely important personal library and scientific collections, including his herbarium. Many of these specimens are the types for some of the world’s most important plants, such as rice, tomato, potato and grapevine.

Linnaeus compiled his herbarium throughout his life, and it forms the basis for how all modern herbaria are created. However, he was not the first person to create an herbarium, as the practice was widespread in Europe before his birth.

One of the earliest known surviving herbaria, dating from about 1558, is the En Tibi, which is short for En tibi perpetuis ridentem floribus hortum meaning ‘Here for you a smiling garden of everlasting flowers’.

This herbarium, made in Bologna, contains 473 plant specimens and is now recognised as the work of the poorly known botanist Francesco Petrollini. He is also believed to have created the Erbario Cibo which, until recently, was attributed to the influential Genoan botanist Gherardo Cibo (1512-1600), who was a student of Luca Ghini (1490-1556).

Ghini was an innovative man and the creator of the first herbarium. He was also the founder, under the patronage of Cosimo I de' Medici, of the first European university botanic garden, the Orto Botanico di Pisa in 1543 (two years before the Orto Botanico di Padova, which retains the title as the oldest botanic garden in its original location).

Botanical artist Lucy Smith and Kew horticulturalist Carlos Magdalene examining the leaves of the newly discovered waterlily Victoria boliviana

Botanical artist Lucy Smith and Kew horticulturalist Carlos Magdalene examining the leaves of the newly discovered waterlily Victoria boliviana

4. The power of herbaria

Ghini’s new method of preparing plant specimens in an herbarium rapidly spread across Europe and ultimately the world.

Unsurprisingly, there were more innovations and changes. They even gained an alternative name: Hortus Hyemalis (Winter Garden), as the preservation of plants enabled admirers to study them throughout the year, even in the depths of the Northern European winter.

One of the more curious and beautiful innovations was the merging of watercolour artwork with the mounted plant specimen. The German botanist Hieronymus Harder (1523 –1607) often painted in elements such as flower and fruit, which were missing from the specimen. At times he also depicted the plants ‘rooted’ into a very simplified landscape.

Herbaria even became an element of the Grand Tour. Collections were made for distinguished guests to botanic gardens such as Padua and Montpelier; the gardener and diarist John Evelyn collected plants when visiting Padua in 1645. His collection, like other herbaria of the time, were bound into volumes; this made managing collections difficult, as botanists were unable to rearrange the specimen’s order to reflect developing knowledge. This challenge led to an important innovation: Linnaeus and his peers started mounting their specimens on individual sheets. This allowed botanists to compare and rearrange with ease.

Today the arts and sciences, unfortunately, tend to inhabit quite different worlds. This was not always the case, as mentioned above. Many scientists of the early modern period were well-versed in the arts and were dependent upon artwork in communicating knowledge.

Within botany, this tradition continues. Recently the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew announced the discovery of an overlooked species of giant waterlily, Victoria boliviana. The discovery was a collaborative project involving global scientific and artistic expertise. In this case the acute observational skills of the botanical artist Lucy Smith (seen above with the waterlily) assisted scientists in observing critical features that separated the plant from its close relatives.

Importantly, the scientific publication that presents the discovery of V. boliviana is richly illustrated with line drawings. One of the benefits of these line drawings is they enable scientists to readily see features that may be hard to observe in herbarium specimens or photography (which is increasingly used in botany).

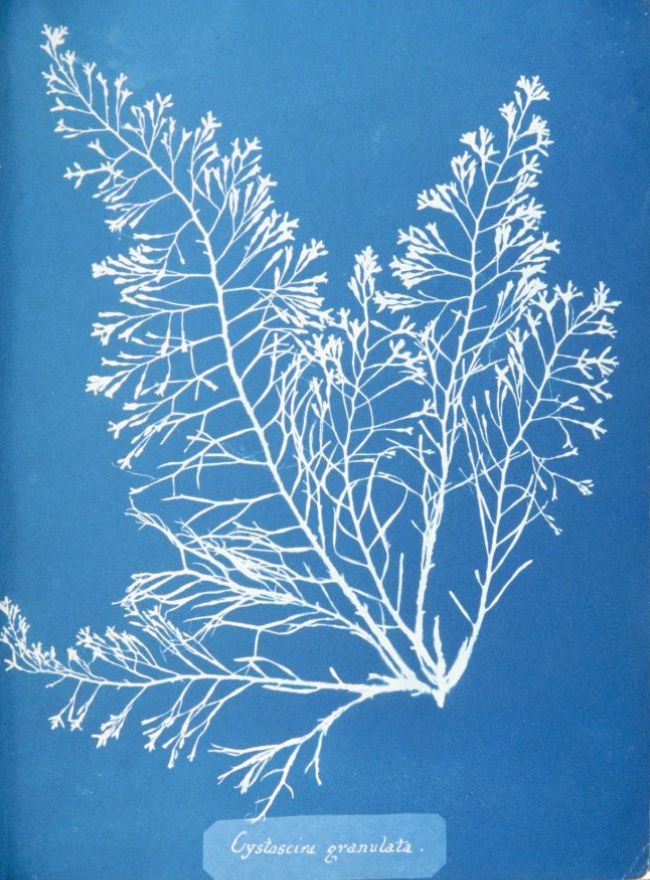

Cystoseira granulata from Anne Atkins’ book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions published 1843-53

Cystoseira granulata from Anne Atkins’ book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions published 1843-53

5. Herbaria as art muse and gateway to history

As described, botanical art is a key component of scientific discovery and uses both living plants and herbarium specimens.

Conversely, herbaria are often an inspiration for the artist.

The early photography innovator and botanist Anna Atkins (1799 –1871), who was the first person to illustrate a book with photographic images, collected her own herbarium specimens, many of which are now in London’s Natural History Museum. The process of creating herbarium specimens doubtless inspired Atkins to produce her three volume Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843-1853). She later collaborated with botanist Anne Dixon (1799 –1864) in producing Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Ferns (1853) and Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns (1854). These works are important in the histories of photography and botanic art.

Herbaria in museums and botanical gardens continue to inspire and welcome artists from around the world. The fashion designer and couturier, Alexander McQueen (1969 – 2010) regularly visited the Natural History Museum collections and used the flowing form of seaweed specimens to inspire designs. And the American conceptual artist Mark Dion (1961– ) used herbarium specimens made from wild plants collected by me and the museum’s volunteers from the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park for his 2007 solo show Systema Metropolis.

Herbaria inspire art; they also connect us with our history – each object is a remnant of the life of the collector, where they went and when. Increasingly herbaria are being used to explore the history of European empire and colonisation, and to illuminate the lives of the people who collected and/or created art from them. Dr Henrie Noltie and his colleagues from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh, for example, have undertaken research to explore the life and works of Indian botanical artists; this research culminated in a significant contribution to the exhibition Forgotten Masters: Indian Painting for the East India Company, curated by William Dalrymple at the Wallace Collection (2019 – 2020).

Herbaria play a vital role in helping us understand plants responses to climate change

Herbaria play a vital role in helping us understand plants responses to climate change

6. Sustainers of human life and wellbeing

Herbaria not only illuminate our past, enrich our arts and help us name plants, they are also vital in exploring the many challenges the world faces today.

Each object is a fragment of environmental data.

Specimens can be used to help us understand how plants respond to shifts in environmental conditions. Their DNA can be used to help study the impacts of plant diseases and to help scientists breed new cultivars of crop that can adapt to the challenges climate change will inevitably unleash.

They can also be used in the most unexpected ways. I use herbaria as part of my work investigating serious crime, particularly murders, as plants at crime scenes can hold secrets. Applying the plant based scientific knowledge of forensic botany can help interpret the events surrounding a crime.

Without the global network of herbaria and natural history collections, humanity would face a culturally poorer and more troubling future. Understanding plants’ place in our world will be vital if we are to continue to thrive on this planet.

Mark’s top tips

Visit, join and volunteer!

Visit your local natural history museum, botanic garden or museum (many local museums have herbarium collections). Most are happy, if they have the staff resources, to accommodate the curious.

If you’re in London and plan to visit the Royal Academy, make some time to visit the The Linnean Society of London, we welcome visitors, have an active lecture programme (both in-person and online) and offer tours.

Volunteer at one of the above. In many cases, these organisations are dependent upon the support of volunteers – you will also learn a lot about their collections.

Join a local natural history society or botany group – the most enjoyable and easiest way to learn about plants is with others!

Get close to plant life

Buy a x 10 hand lens and explore the intricacy of plant form. There is a lot more going on inside a flower or on the surface of a leaf than you may imagine. It will inspire you.

Good reads

Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve and Classify the World's Plants by Barbara Theirs (2020)

Plant: Exploring the Botanical World, Phaidon Editors (2016)

Murder Most Florid by Mark Spencer (2019)

Lucy Smith’s blog on the discovery of Victoria boliviana: https://www.lucytsmith.com/blog/victoria-boliviana-a-new-species-of-giant-waterlily

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers.

Show me another Instant Expert story – theartssociety.org/instant-expert

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition