This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on…the ‘forgotten’ artist Lucy Kemp-Welch

Become an instant expert on…the ‘forgotten’ artist Lucy Kemp-Welch

14 Mar 2023

Famous, then forgotten, Lucy Kemp-Welch was not just a remarkable painter of horses, but a trailblazer for female artists in a world dominated by men. As a show of her work prepares to open, our expert, David Boyd Haycock, reveals her story

For Life (1908) / Courtesy Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

‘Painting horses is, to me, the breath of life.’ Lucy Kemp-Welch

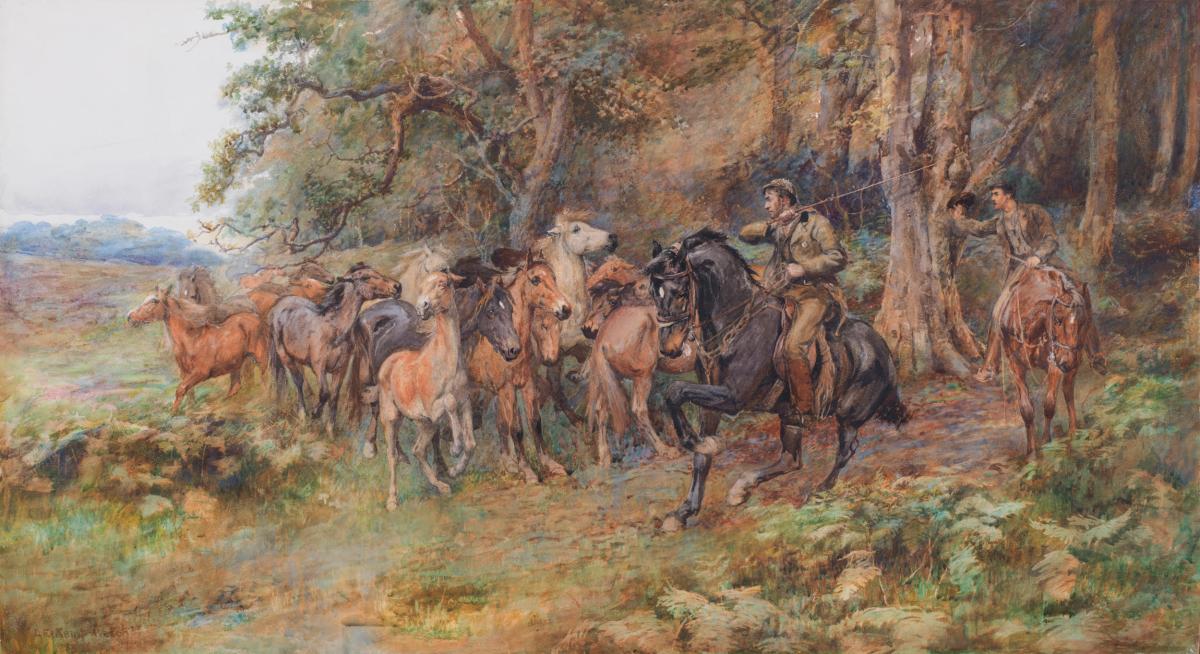

Study for Colt-Hunting in the New Forest (1897) / Courtesy David Messum Fine Art

Study for Colt-Hunting in the New Forest (1897) / Courtesy David Messum Fine Art

1. Causing a sensation

Lucy Kemp-Welch (1869–1958) was only 28 when her huge painting, Colt Hunting in the New Forest, caused a stir when exhibited at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1897. One eminent critic, MH Spielmann, declared that it ‘forces on the world a remarkably talented personality.’

It was not simply the fact that the horses were so brilliantly depicted that made the work a success. As Spielmann explained, it was also that their ‘peculiarities’ were so well observed, ‘and their movements seized with instinctive truth; and this circumstance, in my opinion, marks the difference between ordinary cleverness and talent, which may eventually develop into something more.’

The painting was immediately bought by the Chantrey Bequest and presented to the recently opened National Gallery of British Art at Millbank in London (the building now known as Tate Britain). It was an exclusive honour: even by 1901 there were only five female artists represented in the Tate’s whole collection.

Lucy Kemp-Welch’s youth, gender and extraordinary success made her famous around the English-speaking world. The Times suggested it could only be a matter of time before she became the first woman to be admitted to the Royal Academy since Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser over 130 years before.

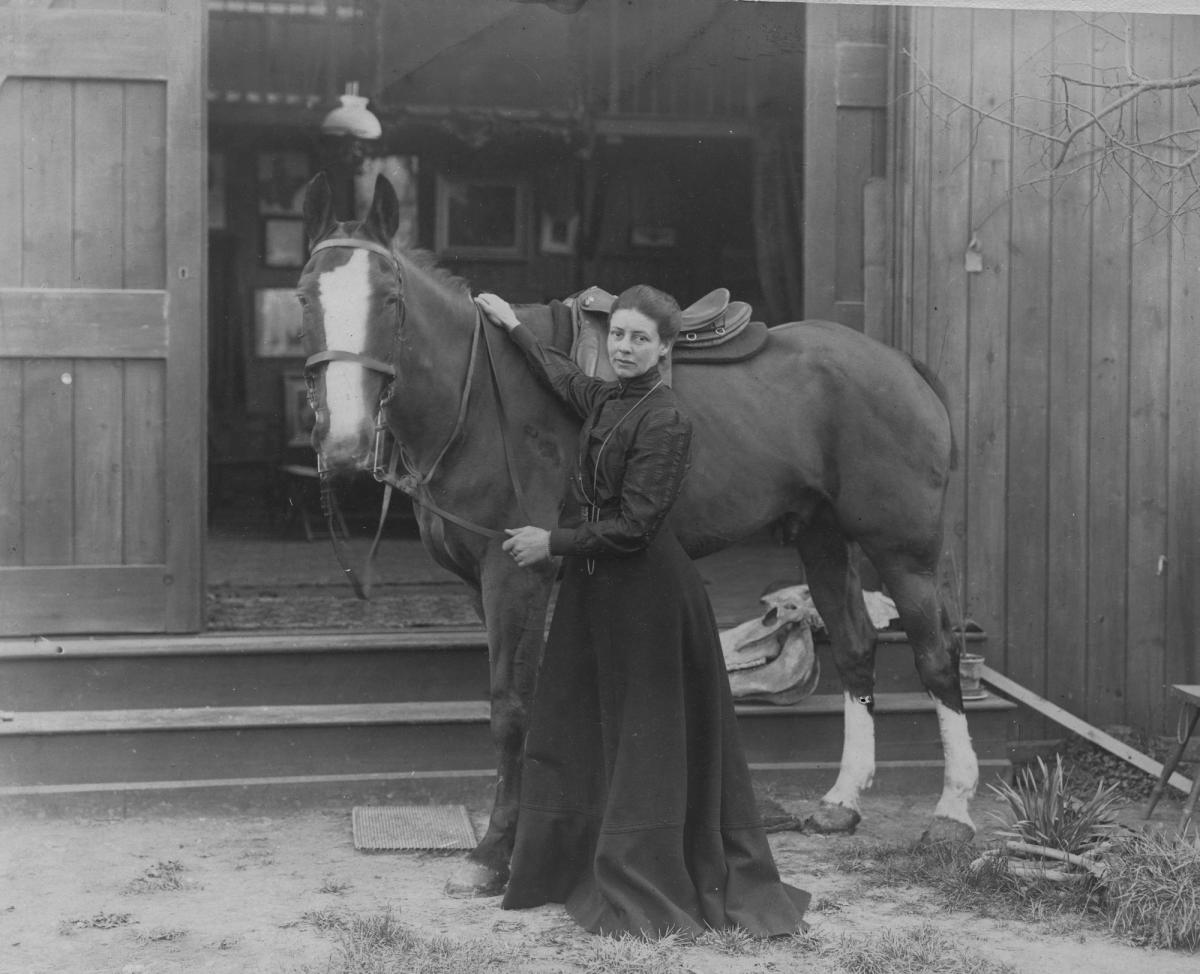

Lucy Kemp-Welch with a horse / Courtesy Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Lucy Kemp-Welch with a horse / Courtesy Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

2. Giant canvasses and equal standing

Lucy Kemp-Welch and her younger sister Edith were born and brought up in Bournemouth. From a young age both were obsessed with animals, and with painting and drawing. Their father, a local solicitor, died from tuberculosis when his daughters were still only teenagers. Their mother died from influenza just a few years later.

The orphaned sisters moved to the little village of Bushey in Hertfordshire to attend the art school established there by the eccentric, but hugely successful German-born British artist, Hubert von Herkomer (1849–1914). Vincent van Gogh had been an admirer of Herkomer’s black and white illustrations in the weekly illustrated newspaper The Graphic, appreciating their strong design and social realism. For a while Van Gogh thought about studying under Herkomer. If he had, the art school at Bushey would be much more famous than it is today.

Herkomer encouraged his students to study nature out of doors. He recommended they spend weeks living right in front of their subject. Kemp-Welch followed his advice, travelling around Britain in search of equestrian subjects to paint, from locations where horses were timber hauling and stag hunting, to race meets and the launching of lifeboats. She set up her large canvases (sometimes as much as 15 feet wide and five feet high) in purpose-built boxes with doors, so they could be left outside in all weather.

Between 1895 and 1930 there was only a single occasion (in 1921) when Kemp-Welch did not exhibit at least one work at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. She showed a further 11 times between 1932 and her final successful submission was in 1949.

When Herkomer retired from teaching in 1906 Kemp-Welch took over, becoming the first woman to run a British art school that included both male and female students. Though she was neither a suffragette nor a feminist, contemporaries saw her as an inspirational figure, paving the way for women in the arts.

The Straw Ride: Russley Park Remount Depôt, Wiltshire, (1919) / Imperial War Museum

The Straw Ride: Russley Park Remount Depôt, Wiltshire, (1919) / Imperial War Museum

3. Strident views

Lucy Kemp-Welch was adamant that her students should not work from photographs. While living in California in the late 1880s the English photographer Eadweard Muybridge had produced a revolutionary series of consecutive shots of horses galloping; but Kemp-Welch thought the camera was ‘fatal’ to an artist.

A photograph was ‘too perfect,’ she argued. ‘It can never leave room for personal temperament to show. All is there except the creative effort. A niggled-up and polished-up picture lacks interest in the same sense ... To be able to copy a model faithfully in every detail is not to be a great artist.’

Her solution to capturing a horse in full gallop was ‘swiftness of observation and rapidity of execution.’ She believed this could only be learnt ‘by the constant exercise of the eye and hand.’ The only ‘photographs’ an artist was justified in taking were those ‘focused and developed’ inside their own brain.

She possessed an incredible facility to retain any visual impression, long after she had seen it. ‘I scarcely know how to explain it,’ she told one interviewer, ‘but it is almost a mental sort of photography. I never forget anything that interests me, and many of the postures of the animals I have painted remain as freshly vivid to me as when I first noted them.’

From dozens of tiny pencil sketches she built up vast masterpieces of observation, such as her epic 1919 painting, seen here, The Straw Ride: Russley Park Remount Depot, Wiltshire.

Study for Big Guns to the Front (1917) / Image courtesy David Messum Fine Art

Study for Big Guns to the Front (1917) / Image courtesy David Messum Fine Art

4. Wanting to go to war

Following the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 Kemp-Welch tried hard to be sent to France to record the conflict first-hand.

Unable to get abroad, she decided in 1916 to paint the British Army training on Salisbury Plain instead. This led to another major work, Big Guns to the Front. Exhibited at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in 1917, it was purchased by the Chantrey Bequest and given to the Tate Gallery. It was exceptional for an artist to be honoured twice. She was then commissioned to paint the official picture for the Imperial War Museum at the Ladies’ Remount Depot at Russley Park in Berkshire (as seen in point 3).

It was Alfred Munnings, her less well-known friend in the Society of Animal Painters, however, who would be commissioned to go to France to paint horses at war for the Canadian government. His work there became the foundation of his future success. It was the clearest example of contemporary gender bias against talented women like Lucy Kemp-Welch.

Although she would be nominated for election to the Royal Academy on a number of occasions, Kemp-Welch would never be successful. The first woman to be elected an Associate of the RA was Annie Swynnerton in 1922. Laura Knight became the first full new female RA in 1936. Munnings would be elected President of the RA in 1944 – a position he held until his death in 1959.

The Aristocrats (1928) / Courtesy Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

The Aristocrats (1928) / Courtesy Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

5. From the circus to Black Beauty

After the World War I Kemp-Welch began painting the famous Sanger’s circus, following it around the country for weeks each summer. But cars and tractors were replacing the working horses that had been such an important part of her life, and her paintings looked increasingly nostalgic and old-fashioned.

By the end of her life Kemp-Welch was too old and weak-sighted to work. She continued to live in ‘Kingsley,’ her house on Bushey High Street, until her death, aged eighty-nine, in 1958. She had never married.

Despite her many years of success exhibiting at the Royal Academy, Kemp-Welch was best remembered for her illustrations for the London publisher JM Dent’s 1915 edition of Anna Sewell’s famous Victorian novel, Black Beauty.

In 1974 the art dealer David Messum acquired her estate, and set about reviving her reputation. Following a host of exhibitions and publications, she is now considered – with Munnings – as the leading British equestrian painter of the 20th century. Next month comes the chance to view her works in a new exhibition, see the details below.

David’s top tips:

See

In Her Own Voice: The Art of Lucy Kemp-Welch (1869–1958) at the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum in Bournemouth; 1 April – mid-October. The exhibition then moves to the National Horse Racing Museum in Newmarket, Suffolk, from late October until January 2024.

You can also view the extensive collection of Lucy Kemp-Welch’s work at Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, Bushey, Hertfordshire. It also holds the best collection of Hubert von Herkomer’s work in the world.

Read

For more on the artist see my book Lucy Kemp-Welch, 1869 – 1958: The Breath of Life (ACC Art Books, 2023).

About the Author

Dr. David Boyd Haycock

Freelance author and curator. He read modern history at the University of Oxford and art history at the University of Sussex, and is now a visiting researcher at Oxford Brookes University. A specialist in modern British art, his books have included A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War (2009) and Brilliant Promise: The Youth of Augustus John (forthcoming June 2023). An Arts Society lecturer since 2011, David offers talks on all the artists he has written about, including Lucy Kemp-Welch, Augustus John, Paul Nash, Eric Ravilious and Stanley Spencer.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition