This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an expert on the great British lido

Become an expert on the great British lido

15 Jul 2020

Take the plunge into a pool of fascinating facts on Britain's lidos.

The sign to Brockwell Lido

1. IS IT 'LEE-DOH' OR 'LIE-DOH'?

This is the first question everyone asks about lidos.

Strictly speaking it’s the former. That’s how the Italians pronounce it, and they should know. The original ‘Lido’ was, and still is, an island in the lagoon of Venice where, since the 1850s, Venetians have enjoyed seawater bathing, glitzy hotels and spa treatments.

The word ‘lido’ itself derives from the Latin ‘litus’, meaning shore.

The first outdoor swimming area in Britain to adopt the name was the Serpentine Lido, in London’s Hyde Park, in 1930. The Times complained huffily that the park now resembled Coney Island, while others, at a time when Mussolini was on the march, lamented the import of an Italian word.

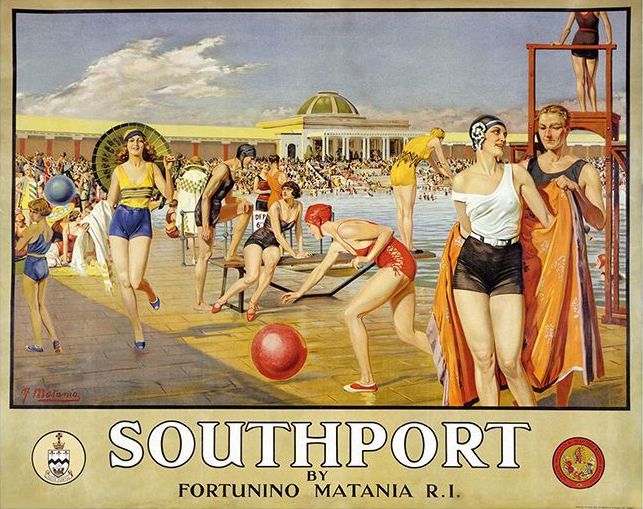

In the north, meanwhile, the likes of Blackpool and Southport carried on calling their outdoor pools ‘open-air baths’. ‘We’ll have none of that foreign nonsense here,’ you can imagine holidaymakers saying, as they left their cafés for the Palais de Danse and a rumba.

As the environmentalist and wild swimmer Roger Deakin once noted, how typical of us awkward Anglo-Saxons to resort to foreign words when considering ‘the pleasures of the flesh’.

Southport Lido rail poster, Alamy

Southport Lido rail poster, Alamy

2. OUT IN THE OPEN

The second question, invariably, is what constitutes a lido?

Well, obviously the chief requisite is a body of open-air water, of which there were many in Britain, long before the lido era.

At Emmanuel College in Cambridge there’s a small outdoor pool that has been in use since at least 1690. It’s referred to as Fellows’ Pool – being in a corner of Fellows’ Garden – but then most swimming, whether in ponds, lakes, rivers or even canals, was a male preserve.

Even when municipal baths started opening from the 1820s onwards, segregation was strict and women’s access was restricted. Queen Victoria was 28 before she took her first dip, from one of those newfangled bathing machines. Eventually, in 1901, the year of her death, reports of mixed bathing emerged from Bexhill, followed in 1910 by mixed sessions at a public baths in Kensington.

The real breakthrough, though, came in the 1920s, and it came outdoors. Liberated from the constraints of Victorian modesty and, thanks to the advent of synthetic materials, from leaden, clinging swimwear, scantily clad men and women could now swim and mingle, unsegregated and unabashed. Lidos became hotbeds of dalliance and display. After all, where better to grab attention than from the top of a diving board?

The fountain at Tooting Bec Lido

The fountain at Tooting Bec Lido

3. SUNTANS AND FOUNTAINS

In addition to a pool, the second, crucial element of any lido is a sunbathing area. Again, this represented a major break with the past.

For centuries, to have a suntan was considered fine for labourers, gardeners or sailors, but not for refined folk. But in the 1920s attitudes changed.

Firstly, army chiefs found that thousands of recruits in the Great War, especially those from cities, suffered from rickets. A Swiss doctor discovered that sunlamps could help tuberculosis sufferers. And then there was Coco Chanel. Having killed off the corset, the French designer made sun worship – or heliotherapy if you must – unutterably chic.

If the lido was a little Italy, its regulars aspired to the Riviera. Crystal clear, filtered water helped too. Hence, from the mid-1920s all open-air pools started incorporating aerator fountains, adding a joyous sparkle to the scene as well as yet another place to sit and soak up the sun (and chat up that girl from accounts). Many such fountains survive, although most are now roped off (for health and safety, we’re told). Sunbathing isn’t considered too clever these days either.

4. PUTTING ON THE RITZ CRACKER

Completing the line-up is the café. Without a café a lido is but a hole in the ground.

Nowadays – as at London’s Brockwell Park – the fare is more likely to be samphire salad and elderflower pressé, rather than crisps and lollies. But along with the lido’s entrance block and changing rooms, the café gave architects an opportunity to join in the fun.

Art Deco and Moderne were the obvious go-to styles. Nautical references abounded. Crittall windows, white render and a railed balcony could transform the simplest of blocks into the deck of an ocean liner.

Margate and Hilsea boasted prominent towers. Portobello, near Edinburgh, where Sean Connery was a lifeguard, had a sleek, cantilevered sunroof that would have dazzled even in St Tropez. Alas it was demolished in the 1980s, as were other treasures (including my favourite, Morecambe’s Super Swimming Stadium).

Sexiest survivors? Grade II* listed Saltdean near Brighton has a gorgeous, curvaceous pool and glazed viewing lounge. Tinside Lido in Plymouth resembles a deconstructed cruise ship artfully reassembled on the cliffs. But other styles are available. Guildford sticks to Home Counties vernacular, while Sandford Parks, Cheltenham has the look of a pristine Arts and Crafts country club.

5. THE GREAT SURVIVORS

Experts Janet Smith and Dr Ian Gordon, both contributors to the Historic England series, Played in Britain, have established that over 300 open-air pools and lidos have operated in Britain since 1800. Today some 125 survive, many run by Friends groups or trusts.

London alone had 67 in 1939, now down to 14. A few remain open all year round, such as London Fields (where, glory be, the water is heated), and Tooting and Parliament Hill Fields (where – eek! – it is not).

For hardy aesthetes, the ultra-elegant Jubilee Pool in Penzance, and more basic Sea Water Baths in Lymington (dating to 1833), offer coastal invigoration, as does Gourock on the Clyde (also thankfully heated). Others may have fewer architectural merits but are in delightful locations, such as Pells Pool in Lewes, Hathersage, Ilkley and, in Wales, Lido Ponty, resplendent since a £6.3m refit.

But if it’s dining rather than diving that appeals, head to the Clifton Lido in Bristol, a quirky backstreet oasis built in 1850, or the Thames Lido in Reading (also intimate, and dating from 1902). At both, the pools form a centrepiece to high-end restaurants and treatment rooms. Aquatic purists may carp, but wait till they taste the bream.

So lido novices take note: just as soon as we are able to visit such sites again, you’re in for a joyful experience.

SIMON'S TOP TIPS

Good reads

Lidos and outdoor, or ‘wild’, swimming have both inspired a wealth of recent writing, but the classic read remains the late Roger Deakin’s Waterlog. It is his account of wild swimming across Britain, and was published in 2000.

For history and campaigning, see the Historic Pools of Britain website.

Check before you travel

Seasonal opening and hours vary from lido to lido – and Covid-19 has affected openings – so before packing your towel, always check first. Most have websites, but a good start is here.

Discover the events

One of the best ways to sample lido life is to attend a special event. Stonehaven Open Air Pool in Aberdeenshire, for example, stages midnight swims to music, while Brockwell Lido puts on summer film screenings. Keep an eye on their websites for the time such events can start again.

Simon Inglis © TAS photographer at Directory Day

Simon Inglis © TAS photographer at Directory Day

OUR EXPERT'S STORY

Simon Inglis has lectured for The Arts Society since 2017, after 15 years editing the Played in Britain series for English Heritage. His theme is the heritage of sport and recreation.

Among his lectures are Great Lengths, on the art and architecture of swimming, Making A Stand and A Load of Old Balls (how balls encapsulate design, technology and human ingenuity).

His book on football grounds was described in The Guardian as the best sports book of the 20th century, while The Daily Telegraph called Simon 'a national treasure who must be encouraged at all costs'. For more click here.

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers, published every fortnight.

All images kindly supplied by Historic England unless otherwise stated

About the Author

Simon Inglis

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition