This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

5 meteorological delights for January

5 meteorological delights for January

8 Jan 2024

Never mind the winter weather: we discover how the best of times and worst of winter’s gales have fascinated artists, through five great artworks

Did you have a white Christmas? No? Perhaps a grey Christmas, or an almost-blue-if-it-wasn’t-for-all-the-clouds Christmas – or an I’ve-no-idea-it-was-too-rainy-to-check Christmas? Certainly, the only thing the UK winter months guarantee is a smorgasbord of weathers, from drizzle to sleet, fog to sunshine, hail to frost. The ever-shifting patterns leave their mark, too, on the canvases and spaces in art, so it’s no surprise artists are so often inspired by wind, rain, sun or snow. While it may be the time of year where it’s best to stay indoors, we encourage you to step out and enjoy the climatic creations of just five wonderful artists.

Snowy Landscape by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), 1850. Image: The Met Collection/Bequest of Julia H Manges, in memory of her husband, Dr Morris Manges, 1960

Snowy Landscape by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858), 1850. Image: The Met Collection/Bequest of Julia H Manges, in memory of her husband, Dr Morris Manges, 1960

Soft as snow

Falling snow, sprinkled like spilled pepper on an icy – yet, somehow, reassuringly cosy – scene forms the basis of this work, which came late in Utagawa Hiroshige’s life and career. Considered the last master of ukiyo-e, a genre of Japanese woodblock prints and painting that reigned supreme during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, Hiroshige had many a landscape under his belt.

Weather is a bit of a through-line, as you might expect of a landscape painter, and given the Japanese focus of his works, snow is a regular feature. This particular piece is housed in the Met Museum’s collection alongside several other works by Hiroshige, including those from his most famous series, The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. The artist travelled the length of the Tōkaidō route, a 319-mile road along the coast of eastern Japan, and captured many sketches on his way. A total of 55 prints were produced, one for each station along the road.

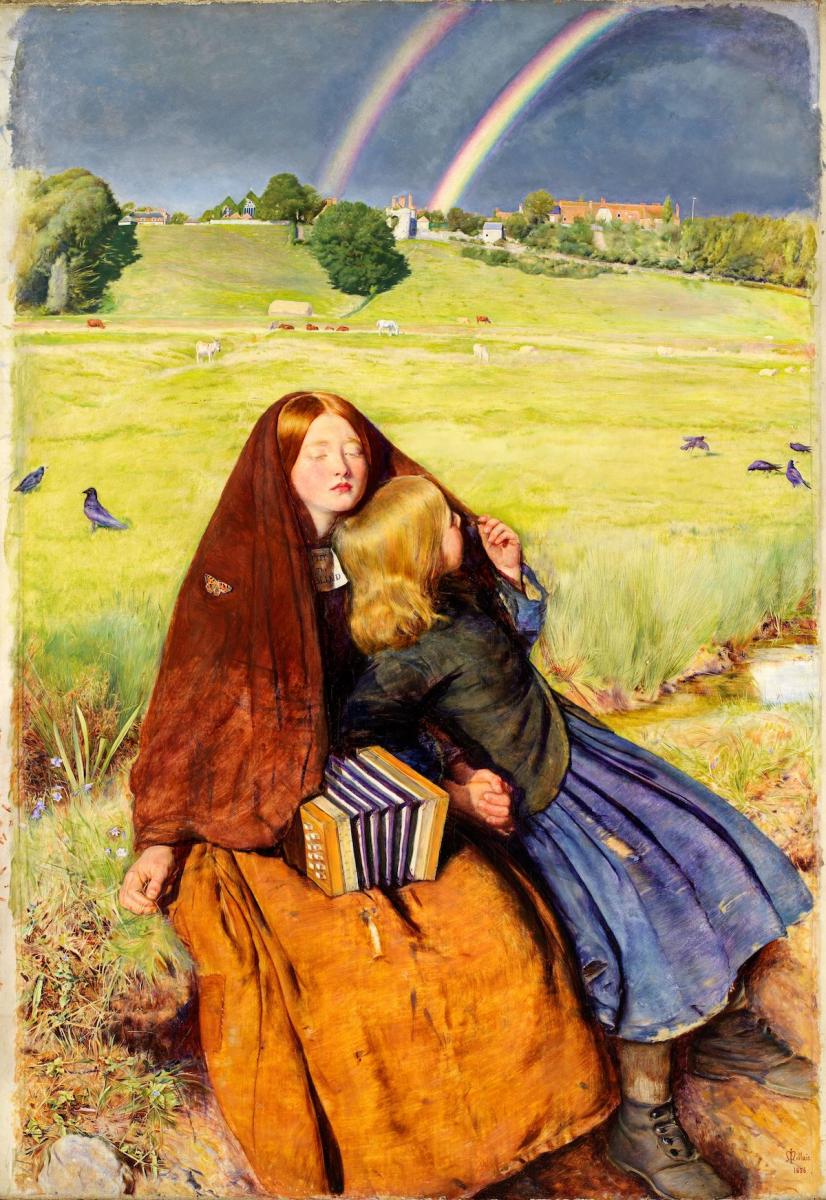

The Blind Girl by Sir John Everett Millais (1829–96), 1856. Image: Birmingham Museums Trust/CC

The Blind Girl by Sir John Everett Millais (1829–96), 1856. Image: Birmingham Museums Trust/CC

After the rain

Weather isn’t just something that is seen, of course. It can be experienced in countless ways: the way the air heaves or droops in the sky before it rains; the whistling of rushing wind; the thick scent of petrichor that emerges after rain.

In this painting by Sir John Everett Millais, not only do we get a vivid rendition of tumultuous storm clouds pressing up against the double delight of arching rainbows, we also see the titular figure feeling for the still-damp grass, her face bathing in the emerging sunshine.

Millais began this work in 1854, initially only including the background of Winchelsea in Sussex. It wasn’t until the following year, and after the artist had relocated to Perth, that he added the two girls. These additions ensured the scene was interpreted as a view of homelessness and disability in the mid-19th century.

The Beach at Deauville by Eugène Boudin (1824–98), 1864. Image: The Cleveland Museum of Art/Gift of Mrs Homer H Johnson 1946.71

Gusts on the canvas

If ever a painting conjured a feeling of needing to wrap up warm and escape the wind it surely is this. Eugène Boudin’s trademark is a Normandy landscape, and here we can enjoy the sight of visiting tourists being caught out by sharp gusts of sea breeze.

The tipped chair, angled sails and sheltered figures all lend to the howls of a windy day at the coast. Boudin’s approach to his works, in which he would paint wood panelling white and then start adding in details without any type of guidelines or drawing, helps to boost the slightly off-kilter effect.

There’s an ongoing debate as to Boudin’s roots: some say he was a self-taught artist, others believe he may have been more closely associated to the Parisian establishment than previously thought. What is clear is that he was among the first French landscape artists to actively paint outdoors, and that he was worthy of his nickname: ‘King of the skies’.

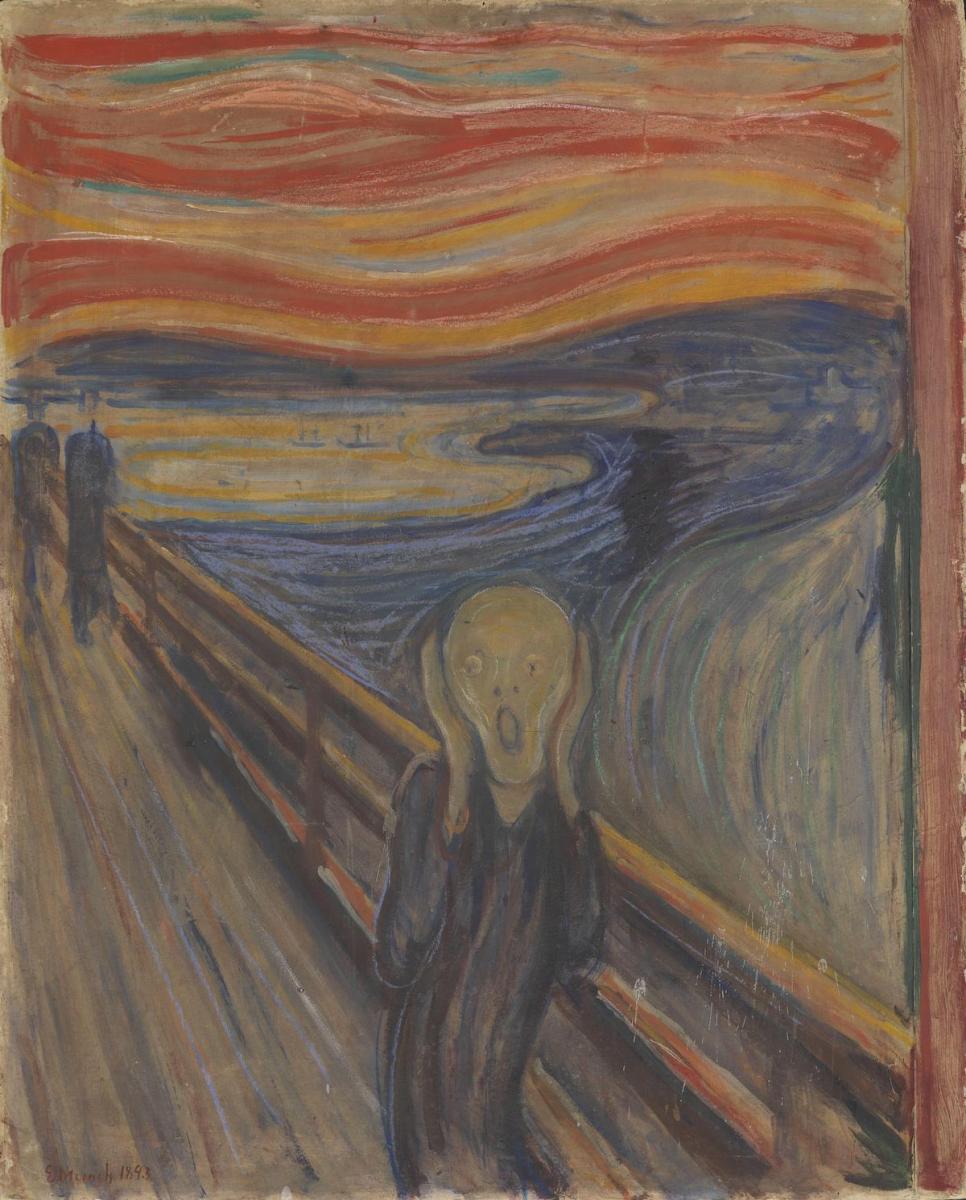

The Scream by Edvard Munch (1863–1944), 1893. Image: Creative Commons – Attribution CC-BY/The National Gallery of Norway

The Scream by Edvard Munch (1863–1944), 1893. Image: Creative Commons – Attribution CC-BY/The National Gallery of Norway

Ribbons of red

Red sky at night, shepherd’s delight? Or, perhaps, shepherd’s scream. One of the most iconic paintings ever made, The Scream is many things, but a vision of firmament joy it is not. Here, the rouge backdrop only heightens the terror – the terribleness of the foreground.

Edvard Munch was inspired by a real red sky, however. He made a note in advance of starting to paint, detailing the inspiration: a walk with friends along a road when the sun suddenly went down, creating a blood-red sky. He describes it as a 'breath of melancholy – an exhausting pain under my heart… a great infinite scream went through nature'.

The artist’s own life mirrored the anxiety that permeates from the canvas. Throughout his life he experienced several mental health difficulties, including what is believed to be borderline personality disorder.

Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson (1967–present) and Minik Rosing (1957–present), Tate Modern version, 2018. Image: Esther Barry/Shutterstock

Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson (1967–present) and Minik Rosing (1957–present), Tate Modern version, 2018. Image: Esther Barry/Shutterstock

Melting moments

No contemporary artwork can look at the topic of climate and weather without at least referencing – or, more often that not, centring – the climate crisis. So it was with Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing’s piece, formed of 24 ice blocks that slowly disappeared in front of passers-by.

The ice itself had been plucked from a fjord in Greenland, and the environmental cost of bringing each one to London’s Tate Modern was reported to be equivalent to that of a flight to the Arctic to see them in their natural habitat. Its stone circle-esque structure was designed to be interactive and touchable, allowing Londoners the chance to see the impact of rising temperatures in a way not normally possible.

The piece had previously appeared in Copenhagen and Paris.

About the Author

Ciaran Sneddon

writes for The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition