This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an instant expert on...the legacy of the Silk Roads

Become an instant expert on...the legacy of the Silk Roads

19 Jun 2023

The name ‘Silk Road’ conjures camel caravans laden with exotic goods, braving inhospitable terrain. It was the route that introduced the Western world to silk. Yet, far more than that, it disseminated inventions, ideas, food and fashion, weaponry and more. Our expert, Chris Aslan, looks at key strands from the story of silk and the routes it has travelled

Afghans travelling to the Pamir Mountains (Afghanistan), site of the ancient Silk Road, c.1800; a 19th-century colour lithography. Photo © North Wind Pictures/Bridgeman Images

Opening routes

The network of trading routes that make up the Silk Road (or ‘Roads’), linking the East with the West, may be ancient, but the term ‘Silk Road’ is a relatively modern one, coined by the German cartographer Baron von Richthofen in the 1880s.

Von Richthofen was mapping out coal deposits in China and, when asked to chart a potential rail route for exporting this coal to Germany, he described it as Seidenstraße (‘silk road’).

Long before then, up until some 2,000 years ago, the East and West were not open to each other. China had developed separately from the Greco-Roman world, divided from it by the marauding nomadic peoples of Central Asia. These nomads were such a scourge that China even built the Great Wall in a failed attempt to keep them out. Finally, in 138 BC, Emperor Wu commissioned a young palace envoy, Zhang Qian, with over 100 men in his charge, to seek out allies among the nomadic Yuezhi, in the hope of combining an attack on the fearsome Xiongnu.

After many misadventures, Zhang Qian reached the Fergana Valley in present-day Uzbekistan. There he discovered heavenly horses so tall, graceful and fleet of foot that later poets said they must have been sired by water dragons. These horses reputedly galloped so fast they sweated blood, and were far superior to the horses in China. Soon, trading horses for silk gave China the cavalry it needed to combat the nomads – and the blockage to trade with the West was broken.

Westerners now had access to the softest silks and muslins, and it wasn’t long before Roman noblemen and women were scandalising society parading in their ‘glass togas’, the delicate materials leaving little to the imagination. The philosopher Seneca complained at the astronomical cost of such materials, as 10% of the Roman treasury was frittered away on these Eastern luxuries. Pliny the Elder harrumphed that a husband now had no more acquaintance with his wife’s body than did any passer-by. Silk became so associated with extravagance that Roman men were banned from wearing it, lest it debauch or effeminise them. But by this time, this new network of trading routes between East and West was beyond such concerns, for it had already ushered in the first age of globalisation.

Modern-day bolts of Uzbek silks: a source of beauty, but in past times such Silk Road bales could host the fleas that carried the Black Death. Image: Chris Aslan

2. From peaches to printing presses

How far did the influence of the Silk Roads reach?

Look in a well-stocked garden. The rhubarb, apples, peaches, hollyhocks, tulips and irises that might be growing there all originally came from along the Silk Roads. Significantly, so too did Chinese gunpowder, which revolutionised warfare.

Another key item was Chinese paper.

Initially used to wrap medicines, paper was cheap to produce and absorbed ink well, making it perfect for printing. The Chinese invented the block-printing of text around two millennia ago, but it was the Uighurs (who originated from Central Asia) who first created a movable-type printing press. This was well over a century before a similar invention in Gutenberg saw the first major book (the Bible) printed in Europe using movable type. Paper and printing were, of course, to revolutionise the dissemination of religions and ideas.

The Silk Road also became a conduit for something much darker. Marmots hunting by caravans passing over the Pamir and Tien Shan Mountains often harboured bubonic plague. Fleas from their carcasses would hop onto bales of merchandise, so carrying the Black Death to Europe.

Conversely, heading to China from the West were wine, olive oil, glassware, amber, pistachio, peas, sesame, dates and even the chair. The first ‘barbarian bed’ to arrive in the East was viewed with suspicion; yet such furniture soon became so popular that houses were built bigger to accommodate the use of items such as chairs, and windows no longer came down to the floor, but to waist height.

In addition, with a nod to fashion, both ends of the Silk Road were influenced by the practical nomadic fashions of Central Asia, adopting trousers and thigh-length kaftans.

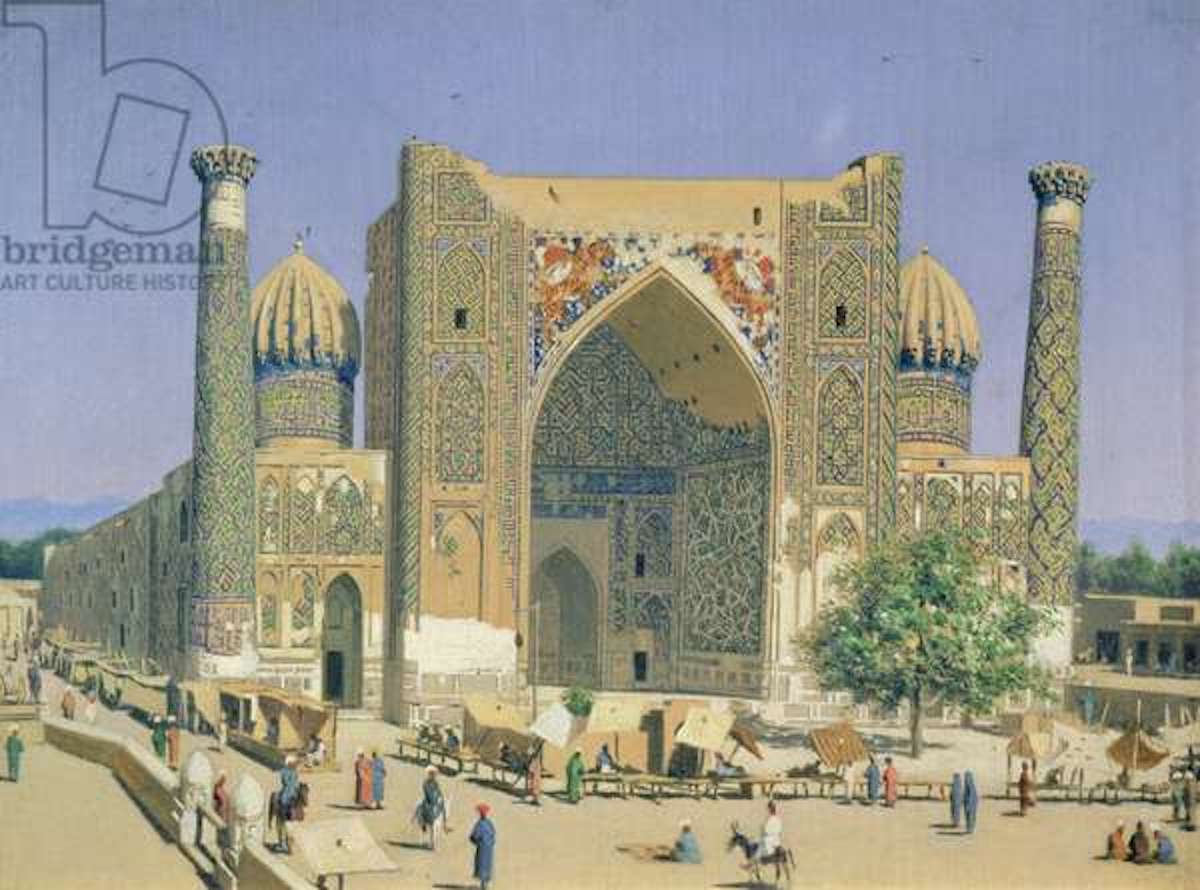

Registan place in Samarkand, 1869–70 by Russian artist Vasili Vasilievich Vereshchagin. Image: Bridgeman Images

Registan place in Samarkand, 1869–70 by Russian artist Vasili Vasilievich Vereshchagin. Image: Bridgeman Images

3. Sweet tongues and silk castles

Few traversed the entire length of the Silk Roads, and if they did, they were usually missionaries or emissaries.

Most of the traders were Zoroastrian Sogdians. They were so prolific that the word ‘Sogdian’ became a byword for ‘merchant’ in Chinese. Boys training as traders went through a merchant ritual with honey placed on their tongues to make them sweet talkers, and gum on their fingers to ensure the money stuck. Sogdians were usually literate and numerate, needing both for trading.

The Sogdians’ capital was in the heart of the Silk Road: Samarkand. The city was the centre of paper-making for the Islamic world and later Europe too. Today, you can still visit paper-making workshops, which utilise the same methods from those times.

While Samarkand was a city largely built out of bricks and wood, there were times when it was transformed into a city of silk.

Gonzalez de Clavijo (d.1412) was a Castilian diplomat who travelled to the court of Amir Timur (1336–1405), the great warring conqueror responsible for the deaths of roughly five per cent of the world’s then population. De Clavijo’s accounts of his visit are rich in detail. He tells how, due to upcoming royal weddings, a silk city of over 14,000 dwellings, able to accommodate 30,000 guests, sprung up in a matter of days on the outskirts of Samarkand. The yurts, tents and pavilions varied in size. Some were used as simple dwellings, shops or bathhouses with running hot water. Others were castle-like in size, with turrets of silk, and could be seen for miles. Silks were encrusted with jewels, embroidered with gold and draped with sable. Surrounding this new silk city was a silk wall.

The sheer scale and opulence of these silk masterpieces were so jaw-dropping that eventually Clavijo concedes, ‘They cannot be described by writing, and they cannot be imagined without being seen.’

A silkworm enjoying mulberry leaves. Image: Chris Aslan

A silkworm enjoying mulberry leaves. Image: Chris Aslan

4. From moth to cloth

There could be no ‘Silk Road’ of course, without sericulture: the process of cultivating silkworms and extracting silk from them.

I first discovered how sericulture works when I started a silk carpet workshop in Khiva, Uzbekistan, reviving carpet designs from the courts of Amir Timur. Uzbekistan has a higher ratio of people involved in tending silkworms than any other country. Every rural roadside in Uzbekistan is flanked with white mulberry trees, grown for their leaves. Each spring the worms hatch out, sized 2mm; within five weeks they are 12cm in length and 10,000 times their original bodyweight. For the first week or so they are kept indoors, with the temperature and humidity carefully regulated. They don’t like raised voices, music, perfume, smoking or the scent of menstruating women. The only thing they do like are the chopped-up buds of new mulberry leaves.

Once they are old enough, the worms are distributed among each village and are tended indoors. As they get bigger and hungrier, each room in the house gets taken over, and the villagers spend their days hacking down mulberry branches to keep them fed. When the worms eventually spin their cocoons, they use a figure-of-eight motion and produce over a kilometre of silk. The silk comes out in liquid form from two spinnerets beneath the silkworm’s mouthpieces. The shape of the cocoon depends on the weather. If it’s been a cool spring they’re longer and thinner, while a warmer spring results in a shorter and fatter cocoon.

The weaving capital of Uzbekistan is Margilan in the Fergana Valley. Here, ikat silk, known as ‘Atlas’, is still produced in the traditional way, using a resist-dye technique on the warp threads. Handmade velvet is also popular, made with two layers of warp threads. The floating warp is pinioned between metal rods and weft threads. The rods are then sliced away, creating a luxuriant pile.

Vibrant Atlas silks drying in Margilan. Image Chris Aslan

Vibrant Atlas silks drying in Margilan. Image Chris Aslan

5. Silken trails

From the Silk Road we have silk – and from silk has come surprising developments.

Let’s start with its making.

Complicated brocade silks originally required two weavers. One sat at the loom weaving, but the other was perched above, carefully lifting the correct numbers of warps to insert additional decorative weft threads. Eventually this process was mechanised by the jacquard loom, which utilised a series of punch cards – a little like a pianola roll – to create beautiful brocades.

This punch card mechanism was the forerunner to the early computers.

Then there is silk’s role in disease prevention. Due to the intensive nature of sericulture, outbreaks of disease were disastrous. It was attempts to prevent outbreaks and epidemics within Lyon’s thriving sericulture industry that gave Louis Pasteur his guiding principles for epidemiology, which are still used by modern science today and led to Pasteur pioneering vaccines.

And we can’t explore the legacy of silk without looking at World War II.

Silk, given its remarkable strength-to-size ratio (it has a greater tensile strength than steel), was vital for parachutes. It was also used to create secret maps that could be sewn into clothing. In addition, silk sutures were used for the wounded.

Bringing the story to current times, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, countries along the Silk Road, such as Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, have opened for tourism. This has led to a revival of beautiful silk embroideries, velvets, ikats and carpets. Travellers today, ready to explore the Silk Road and its stories for themselves, are doing their bit for the revival of handicraft industries that were destroyed under Soviet rule.

Chris’s top tips

Great reads

Traditional Textiles of Central Asia by Janet Harvey

Silk and Cotton - Textiles from the Central Asia That Was by Susan Meller

Silk Roads - Peoples, Cultures, Landscapes, edited by Susan Whitfield

My own book Unravelling the Silk Road has just been published by Icon Books

Visit

The V&A Museum has a wonderful collection of 19th-century suzanis (embroidered and decorative tribal textiles), which are not currently on display. They can be viewed online at collections.vam.ac.uk or with an advanced booking.

There are many excellent tour operators that travel the Silk Road. I lead tours with Indus Experiences.

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

About the Author

Chris Aslan

is an author, tour leader and Arts Society lecturer. He was born in Turkey and grew up there and in Beirut. After university he moved to Khiva, a desert oasis in Uzbekistan, establishing a UNESCO workshop reviving 15th-century carpet designs and embroideries, becoming the largest non-government employer in town. His book A Carpet Ride to Khiva: Seven Years on the Silk Road covers his experiences there. He has also spent several years in the Pamir Mountains of Tajikistan, training yak herders to comb their yaks for their cashmere-like down; and time in Kyrgyzstan, where he lived in the world’s largest natural walnut forest, establishing a woodcarving workshop. Among Chris’s lectures for The Arts Society are The golden road to Samarkand: the architecture, art and textiles of Uzbekistan; Cosmonauts and cotton pickers; Soviet Central Asian mosaics and the use of public art as propaganda and Unravelling the Silk Road. He also offers Study Days on Unravelling the Silk Roads.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition