This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on… the dinosaurs of London’s Crystal Palace

Become an Instant Expert on… the dinosaurs of London’s Crystal Palace

13 Oct 2021

Who knew there were dinosaurs in Crystal Palace? You’ll find them in the world’s first dinosaur park, which opened in 1854. Today its Grade I listed models provide a snapshot of our understanding of dinosaurs at the dawn of palaeontology. Our expert, Dr Aaron W Hunter, takes us on a tour

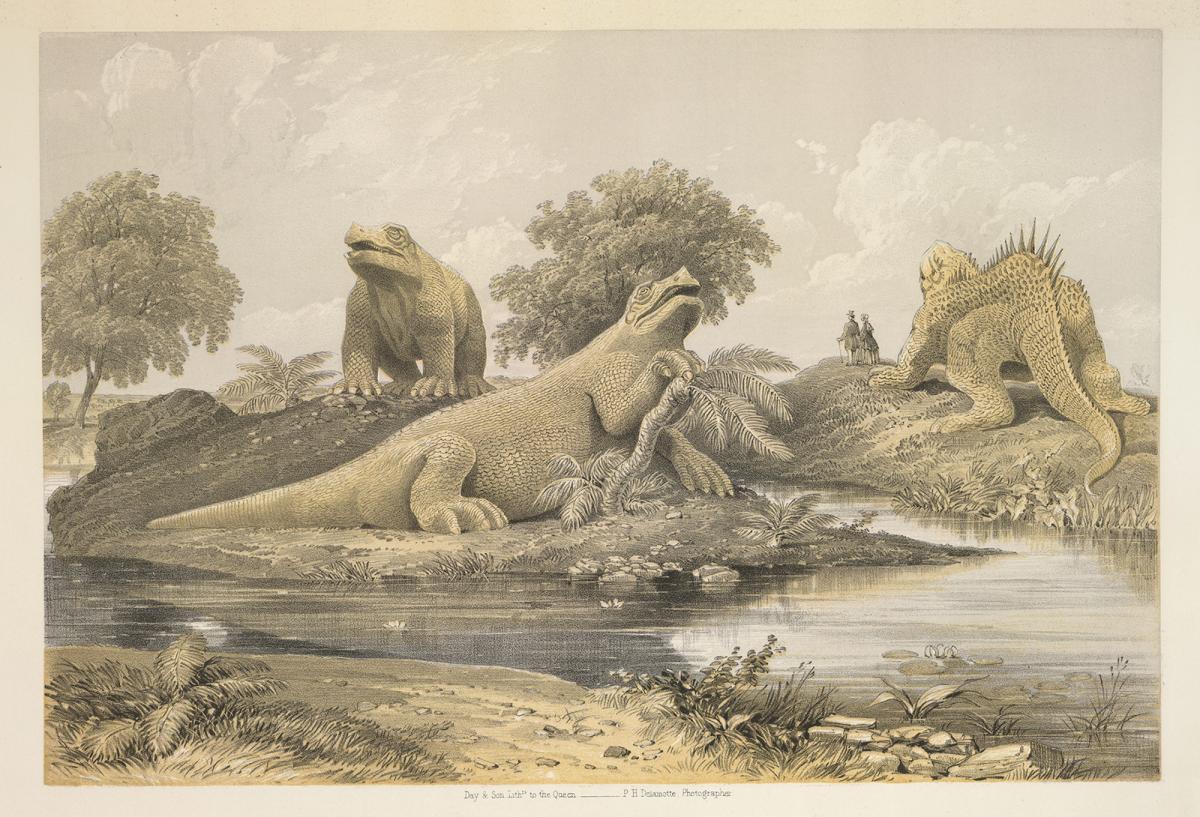

The newly unveiled models of ‘extinct animals’ in Crystal Palace, 1854

1. A world first

The Great Exhibition building known as the Crystal Palace moved from Hyde Park to a greenfield site on Sydenham Hill in Kent (now Greater London) in early 1852. Its designer, Joseph Paxton, had formed the Crystal Palace Company to purchase the building for £70,000 (almost £10m in today’s money). It was on the new site, in the extensive parklands, that a group of scientists then embarked on a highly innovative new project.

They wanted to create the world’s first full-scale reconstructions of extinct dinosaurs. Unlike the creatures they represent, those models are still with us today, and the first thing to note is that they are not all dinosaurs. Only three can be classified as such, while the rest are amphibians, reptiles, sea dragons (marine reptiles) and mammals. Being that the science of palaeontology was in its infancy, these models also look different to the way scientists today understand how they would have originally appeared.

The first dinosaurs and their marine reptile cousins were found in strata in England, although the bones of ancient animals had already been found across the known world. Until then, English discoveries had been thought to be the remains of giants. But the discovery of teeth and skull remains, along with work by geologists establishing the antiquity of the Earth, led natural scientists to propose that the findings were actually the remains of ancient reptiles. The scientist and artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was the man who set about creating the models, with the assistance of Sir Richard Owen, the superintendent of the natural history department of the British Museum. In Hawkins’ workshop, close to the southern end of the park in Sydenham, he first made full-size casts in plaster, casting the models themselves in concrete reinforced by coarse pebbles.

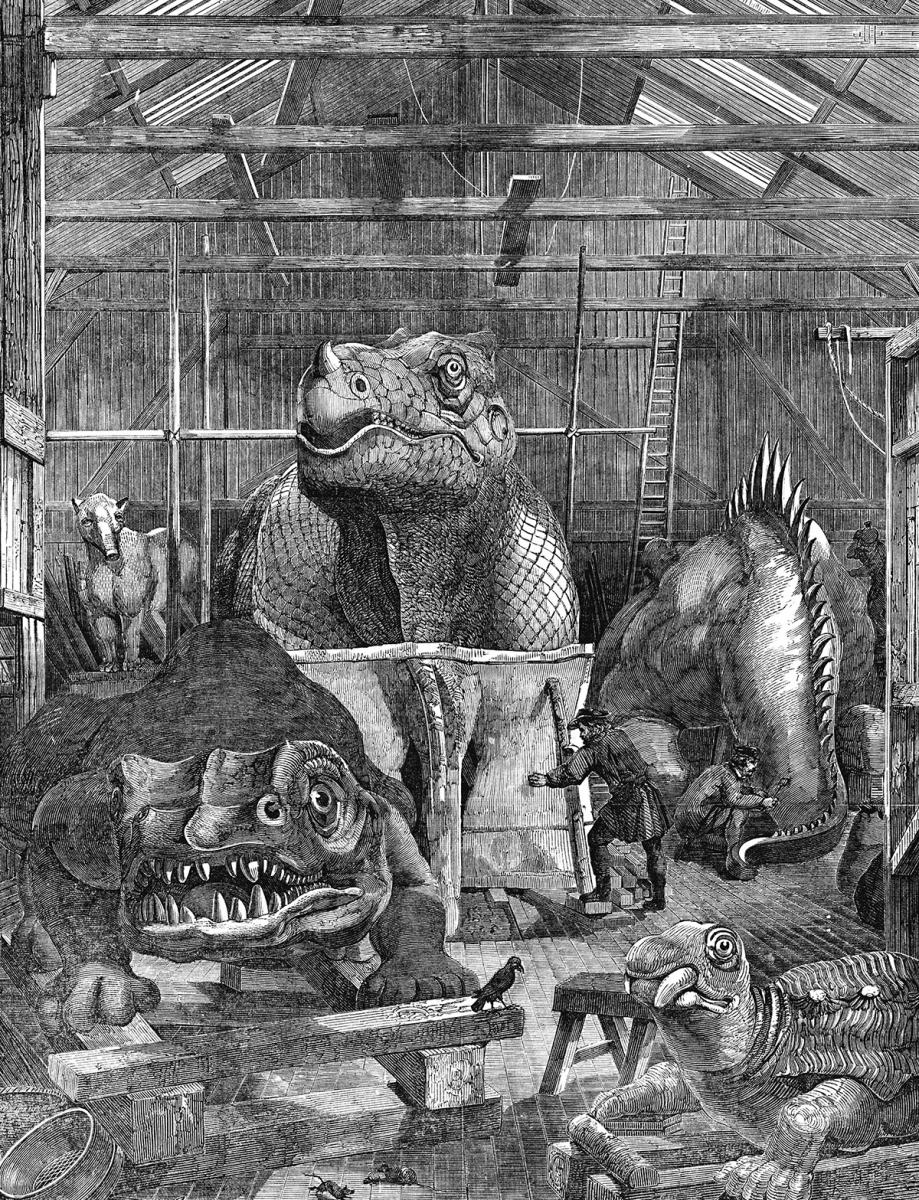

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins at work in his studio, where he made the Crystal Palace dinosaurs

2. Ancient strata and colours

The completed models were to be placed on a series of artificial islands within the lakes at the base of the hill, with the Crystal Palace and fountains towering above. Before they were ready, there were challenges to face, not least what colours the scientists should choose to paint the beasts. There are still many things we do not know about dinosaurs, and the hue of some of their skins has only been a recent discovery. Over time the dinosaurs of Crystal Palace have been painted a variety of colours. In the latter half of the 20th century the park’s custodians had them painted bright green, to match what they were seeing at the cinema.

Recent conservators have stripped back the layers on the models to discover that each set of animals was originally painted the colour of the strata in which their fossil remains were discovered. These colours match those found on the world’s first geological map of any country – A Delineation of the Strata of England and Wales, with Part of Scotland – created in 1815 by the canal engineer and father of English geology William ‘Strata’ Smith.

Matching the colours to the strata was a clever way of informing visitors that they were about to go on a time walk – through over 250 million years of evolution – without leaving this corner of Crystal Palace. The scientists were not merely content with painting the models geological colours; they also wanted to bring geological elements to a city that does not have much to see in terms of rock features. As a result, today, on one side of the park, you can find an example of recreated rock strata, including layers of ‘economic geology’ such as beds of coal, a fault through the rocks and a break in the strata geologists call an unconformity – all created by Joseph Paxton and Professor David Ansted, a noted professor of geology of the time.

A 19th-century colour engraving of the dinosaurs in their landscape

3. Starting your tour

Take a tour of the park today and, on reaching the first island, you will find both animals there painted pink, to represent the sandstone that their fossils were found in. These were the beasts that inhabited the desert landscapes of the time of the Permo-Triassic, around 250 million years ago, when the Earth's continents had come together to form a single supercontinent called Pangea. Here we find, placed next to each other, animals that would actually have inhabited very different worlds.

First we have Labyrinthodon (or maze–tooth), which is not a reptile but a giant amphibian that would have lived in the swamps of northern Europe. Secondly, we find the large reptile-like cows called the Dicynodon, which would have once roamed the deserts of what is now South Africa.

At the next island we arrive at the shallow seas of the Jurassic to meet the sea dragons found within the cliffs of the Dorset town of Lyme Regis. These ‘dragons’, ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, were discovered by the 19th-century fossil hunter and commercial dealer Mary Anning. Not accepted as a professional in her day, she was still a pioneer, making notable discoveries that included the fish lizard or Ichthyosaurs, here painted a light grey to represent the 180-million-year-old limestone and mud rocks of the Lias strata of Lyme Regis.

The Ichthyosaurus here is a creature that looks like a cross between a crocodile and a seal. Later fossils found in Germany establish that it was in fact much closer to a shark or a dolphin in terms of body shape. The Ichthyosaurs models are adjacent to the Plesiosaurus which, with its long neck and little head, looks like popular depictions of the Loch Ness Monster. The Victorian scientists, however, found it hard to believe an animal could have a neck that long, so they made the model look more like a snake attached to a long body.

Meet the sea dragons: Labyrinthodon and Dicynodon

4. The real thing – and a special banquet

As we move from the island onto the land, the colour of the animals changes to the light green of the early Cretaceous period of around 100 million years ago. This was a time of ancient crocodiles called Teleosaurus. Now we see the real dinosaurs.

The first dinosaur in history to be named formally, found in strata not far from Oxford, was Megalosaurus – discovered by the geologist William Buckland, a find he made public in 1824. The ‘great lizard’s’ pointed teeth clearly identified this animal as a carnivore. Perched on a rock behind is a pterosaur, or flying reptile, discovered from same-age rock strata in Germany. Despite being painted green, both these animals are actually Jurassic but younger than Anning’s sea dragons. Here, too, is the Iguanodon.

The surgeon Gideon Mantell and his wife Mary Ann, both amateur palaeontologists, discovered the remains of Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus in 1822. Iguanodon (or iguana tooth) was a herbivore or plant eater. The couple discovered teeth and fossil bones but not enough to know what the full skeleton would have looked like. The discovery of a rhino-like horn – and their frequent correspondence with the French zoologist Georges Cuvier – led them all to believe that these animals looked a bit like rhinos, when in fact our current reconstructions are different.

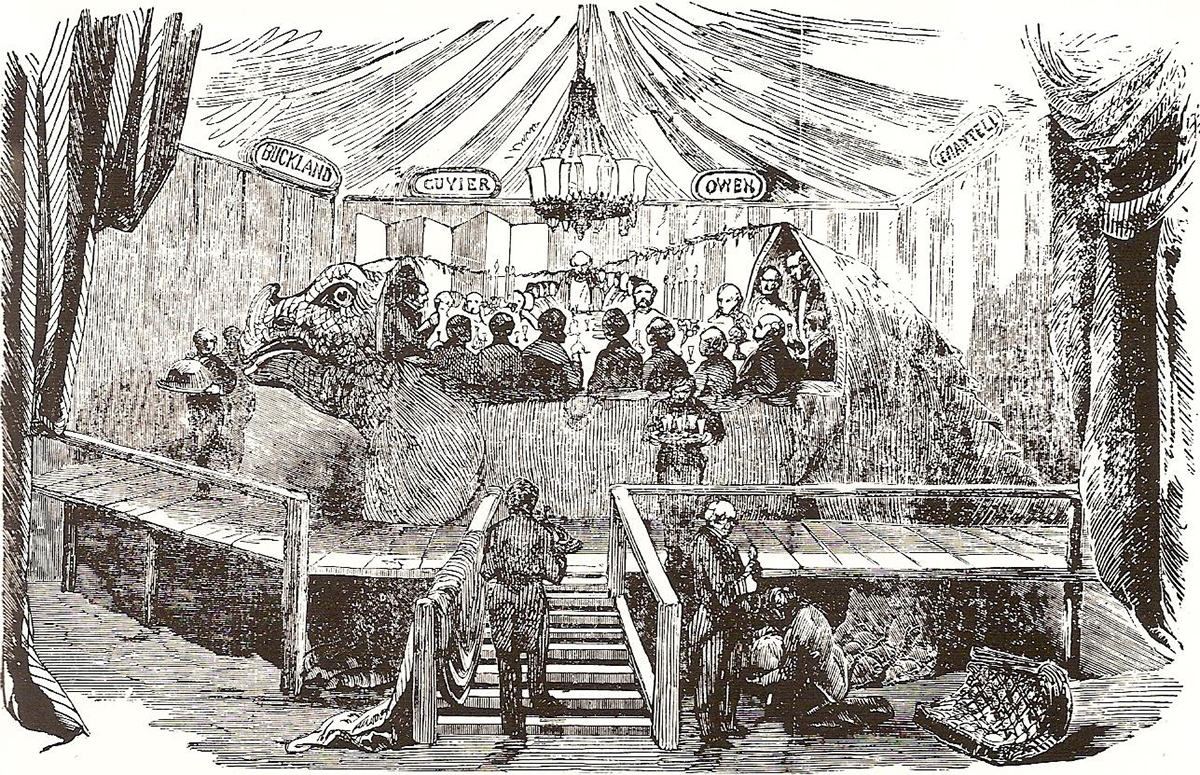

It was in a cast of Iguanodon that Waterhouse Hawkins held a remarkable celebratory dinner to gain publicity for this project. It was attended by Buckland, Mantell and Cuvier, along with Sir Richard Owen (who had coined the name ‘dinosaur’ in 1842) and others, including some newspaper editors. Called the ‘Dinner in the Dinosaur’ (or as Punch proclaimed it, ‘Fun in a Fossil’), it was held on New Year’s Eve, 1853. Dinner started with mock turtle soup and finished with fruits and walnuts.

The famous banquet in the mould of the Crystal Palace Iguanodon, New Year's Eve, 1853

5. The rise of the mammals

As we move to the last island, we catch a glimpse of Mosasaurus, another sea dragon that inhabited the oceans just before the mass extinction that wiped dinosaurs out 65 million years ago. The extinction of the large dinosaurs (birds, which are small dinosaurs, are of course still with us today) allowed the mammals, which to this point had been small, to evolve into animals we would recognise today. These new, larger mammals represented in the park are painted a light brown, in reference to the clays found in England, and specifically around London, that are around 50 million years old.

The models include Palaeotherium, a distant relative to the horse, or Anoplotherium, thought to be related to camels. During his voyage on the Beagle, Charles Darwin was to see the remains of extinct giant mammals in Patagonia. These include the Megatherium, or giant sloth, which here in the park can be seen rearing up next to the boating lake. The last animal on our tour is the only one that might have been encountered by humans. It is Megaloceros, which lived less than 13,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age; sometimes called the Irish elk, it was often found preserved in Irish peat bogs.

Last sighting on your tour: the Megaloceros

Aaron’s top tips

See

You can view the Crystal Palace dinosaurs for free, when the park is open. The models are fragile and at risk and are now looked after by volunteers of Friends of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, who run events throughout the year to promote the sculptures; find out more here.

The best place to see fossil remains is London’s Natural History Museum. Its excellent collection of marine reptiles includes those discovered by Mary Anning. You can also see the remains of the first British dinosaurs, such as Iguanodon, and the more recent discovery of the fish-eating Baryonyx from Surrey.

The original Megalosaurus can be seen at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Discover a fascinating collection of Jurassic marine life, collected by fossil hunter Dr Steve Etches, at the Etches Collection in Kimmeridge in Dorset.

The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences at the University of Cambridge is a great place to come face to face with the ancient fossil remains of a hippopotamus and an Irish elk (Megaloceros).

Dinosaur Isle is one of the first purpose-built dinosaur museums in Europe; you’ll find it in Sandown on the Isle of Wight, designed by local architects Rainey Petrie Johns in the shape of a giant pterosaur. The island is one of the richest dinosaur localities in Europe, and new discoveries are constantly being made.

The best-preserved dinosaur in England, Scelidosaurus, can be found at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery; and the largest complete skeleton in Britain, if not the world, the 'Rutland Dinosaur', or George, a 15-metre-long Cetiosaurus, can be seen at the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery.

Good reads

The Fossil Woman: A Life of Mary Anning by Tom Sharpe. For the early history of geology, The Map That Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology by Simon Winchester. An introduction to all things dinosaur can be found in The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs by Steve Brusatte. For life before the arrival of dinosaurs, see When Life Nearly Died: The Greatest Mass Extinction of All Time by Michael J Benton.

If you enjoyed this Instant Expert feature why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too? Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers. Show me another Instant Expert story

Image credits: British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images, Sydenham Studio, Look and Learn / Peter Jackson Collection / Bridgeman Images, AW Hunter

About the Author

Dr Aaron W Hunter

Dr Aaron W Hunter is a palaeontologist, geologist and guide-lecturer with the University of Cambridge. He is also a history of science specialist Blue Badge Guide for London, running tours and giving lectures. His PhD from the University of London was on the Jurassic fossils and strata of the UK and the USA, and he likes to guide and lecture on the animals that existed during the time of the dinosaurs, as well as the Victorian scientists who discovered their remains. He is an active researcher focusing on the early evolution of animals over 485 million years ago. Among his current lectures for The Arts Society are The Jurassic World of Mary Anning, Urban Geology of the City of London, The Science of Art at the National Gallery and The Dinosaur Sculptures of Crystal Palace. He first visited the dinosaurs there when on the way to see his grandparents, who used to live just around the corner.

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition