This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Who says it's a masterpiece?

Who says it's a masterpiece?

19 Mar 2021

How do we recognise an outstanding work of art – and who are the ‘we’? Arts Society Lecturer Dr Caroline Levisse reveals her theories.

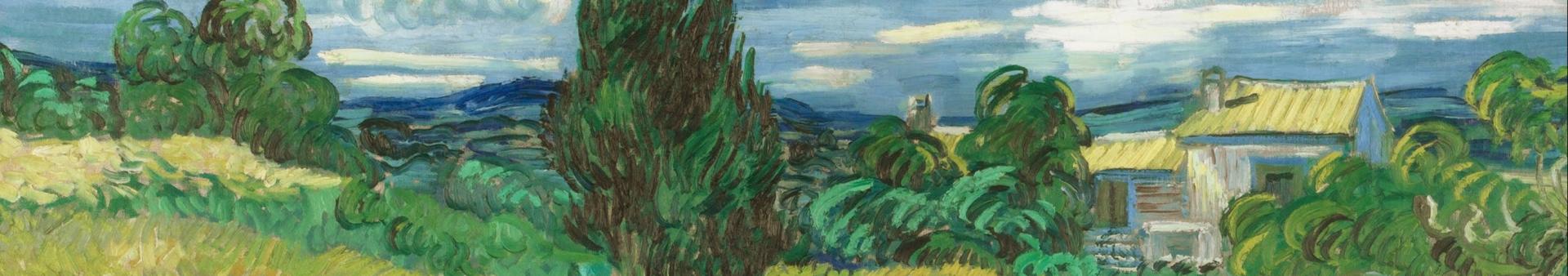

Vincent van Gogh’s Green Wheat, 1889

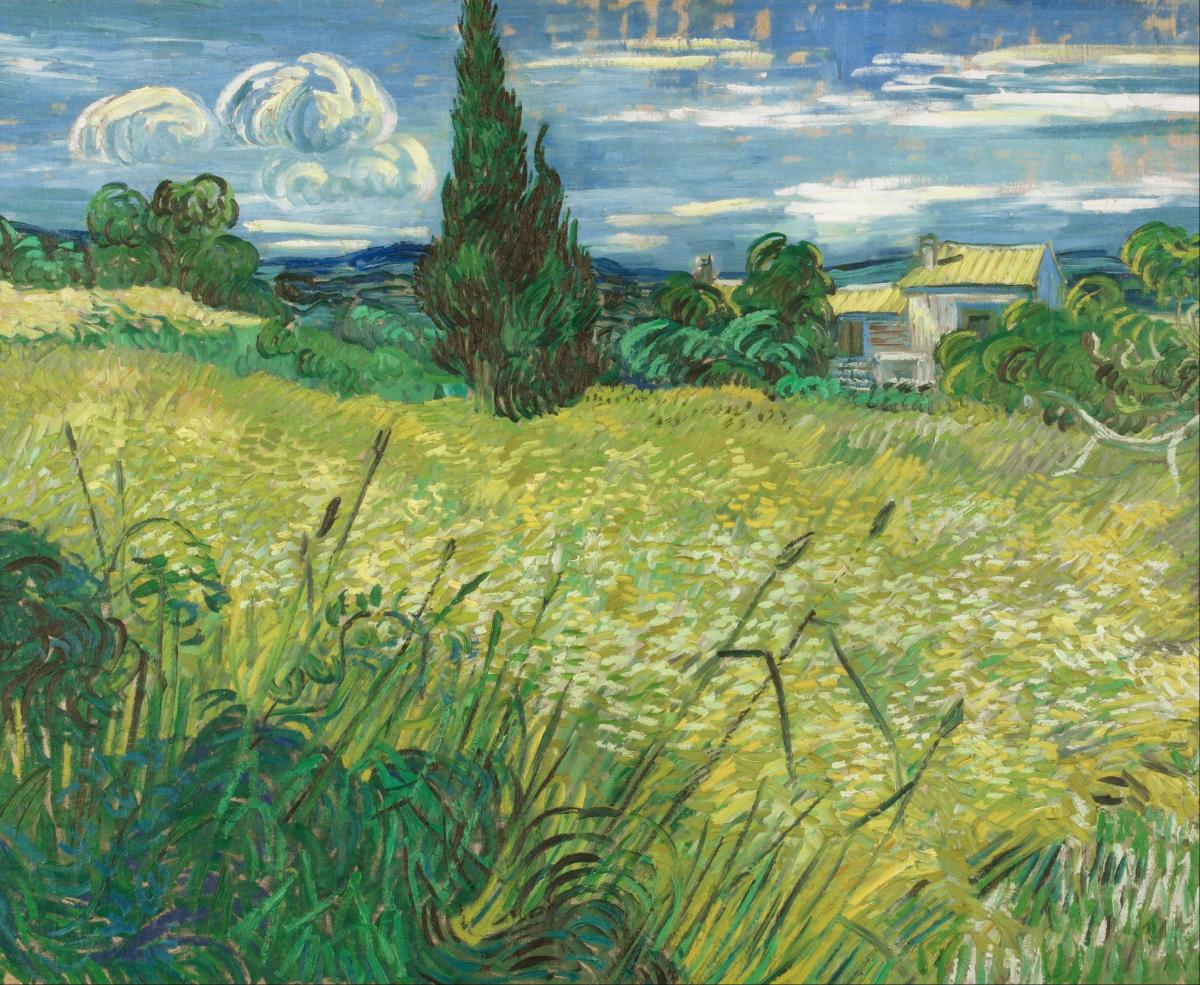

When the word ‘chef-d’œuvre’ – (‘masterpiece) – first appeared in French medieval documents, it referred to the work created by a craftsman to mark the end of his apprenticeship. This was a form of examination, during which the apprentice would demonstrate his skills, his savoir-faire. Success was determined by the ability to execute a piece to perfection, dans les règles de l’art (or ‘by the book’). During the Renaissance, painting and sculpture were newly considered as ‘art’ rather than a trade or craft, and art academies replaced guilds as an authoritative and organising body. From then, creativity became increasingly important in the making of an outstanding work of art. In his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550), Giorgio Vasari celebrated artists’ technical virtuosity and their unique vision and inventiveness. Michelangelo’s David and Leonardo’s Mona Lisa are two excellent examples.

It is in the 19th century that the concept of ‘masterpiece’ becomes truly important for the history of art. While public art museums were still a relative novelty (the Louvre opened in 1793, the National Gallery in 1824), and art history was a burgeoning academic discipline, experts wrote the story of art as a succession of great moments, or steps, towards the present. This story of artistic evolution was neatly packaged in the so-called canon of art.

Michelangelo’s David

Michelangelo’s David

From Van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb to Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel, the canon tells us which are the best works to have been created. It represents an ideal of perfection for aspiring artists to emulate (or defy), and art lovers to admire and collect. As this cultural norm became part of our basic art education, it shaped our taste and expectations.

How do art historians choose which works are the greatest? They have a range of criteria, such as the exceptional quality of execution, showing a mastery of the medium; the efficient communication of a meaningful story, idea or emotion; the originality and inventiveness of the work; its complexity; and its historical significance. But perhaps the most distinctive trait of a masterpiece is its ability to endure, despite changes in society. In a 1979 essay, ‘What is a Masterpiece?’, art historian and broadcaster Kenneth Clark mentioned the ‘extraordinary fact that they can speak to us, as they have spoken to our ancestors for centuries’. In other words, the concept of the masterpiece refers to a special class of art; works that are so great they transcend historical boundaries and have a universal value. The profound humanity we encounter in some of Rembrandt’s portraits still has the power to move us, making these works masterpieces of portraiture.

‘IT IS TEMPTING TO ABANDON THE IDEA OF THE MASTERPIECE AS AN OBSOLETE CONCEPT’

However attractive, this universal claim became problematic. For decades, art history has been facing its biases, demonstrating that its central narrative reflects the values of a specific group – an elite. In her 1971 essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, Linda Nochlin explained how the criteria for greatness are ‘rigged’ in favour of a particular group, excluding others. This also affects viewers. For the many not of the elite, the masterpieces forming the canon of art may feel at odds with their lived experience and collective history. It is tempting to abandon the idea of the masterpiece as an obsolete concept tailored for a bygone world, and adopt a more relativistic approach. But if we are to hold on to the conviction that some creations are more extraordinary than others, worth preserving and sharing with as many as possible, we need to adapt the definition of the masterpiece and make room for a wider range of experiences.

OUR EXPERT’S STORY

• Caroline is an art historian who specialises in modern European art, with a focus on Scandinavia

• One of the courses she teaches is ‘What makes a masterpiece?’, which has led her

to study this essential topic

• Among her talks for The Arts Society are The colour blue in Western art, Danish Modernism: the Skagen painters and What makes a masterpiece?

About the Author

Dr Caroline Levisse

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition