This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the Snowy Egret Feather

Become an Instant Expert on the Snowy Egret Feather

27 May 2020

Tessa Boase reveals the Victorian and Edwardian tale of the hunt for snowy egret feathers: a yarn of fashion, fury and protest, which led to the founding of one of the UK’s best-known charities.

1. THE CULT OF THE ‘OSPREY’ WAS A STRANGE ONE

Starving egret chicks: by Australian orinthologist Arthur Mattingley, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria

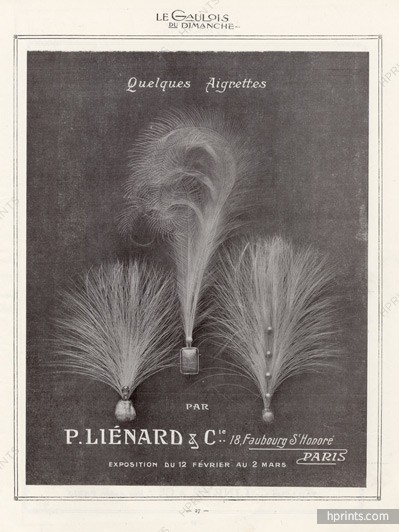

On a wet Wednesday in March 1888, a record-breaking plumage sale was held at the London Commercial Sale Rooms. Among the many thousand bird of paradise, hummingbird, parrot, crested grebe and lyrebird plumages on sale were 16,000 packages of ‘osprey’.

Today, osprey has just one meaning: the magnificent sea eagle. But between 1870 and 1920, when the fashion for feathers swelled to obscene proportions, the ‘osprey’ meant an upright, tufty millinery ornament made from the fine, breeding plumage of the great and snowy egret. It was the cruellest plume of all to harvest, depriving chicks of their parents. And it was to become the most potent emblem for the campaign against feathered hats.

What was the allure of this white, wispy, uninteresting feather? When bunched together en masse, those wire-like fine filaments would almost levitate from a hat, creating an aureole, as if the head was backlit by the sun. Dyed black, they were lustrous, sophisticated, scintillating. They could also be bought in every other colour in-between, from Edwardian hostess Maud Messel’s pale-pink collection (held today by the Brighton Museum), to the lime-green exclamation mark worn by one Major Drummond’s social gadfly wife.

By the turn of the century, every woman, of every class, had to own one.

2. THE PLUME HUNTERS REIGNED SUPREME

As global demand boomed, hunters got rich. David ‘Egret’ Bennett was a celebrity plume hunter, operating at the turn of the century from his mansion in San Diego – ‘probably the most experienced and systematic hunter of wild egret or heron in the world,’ enthused the New York newspaper The Sun.

For two decades he and his gun had ruled supreme in the egret and heron colonies on the west coast of Mexico, where he’d disappear for weeks at a time during the long nesting season, slipping back into civilisation to dispose of his stock. At the time of The Sun’s 1896 interview, Bennett had just shifted $2,600-worth of feathers to wholesale plumage buyers in New York and Philadelphia (around £50,000 in today’s money). In 1896, an ounce of feathers was worth $28 – and each bird might yield a quarter of an ounce of feathers.

‘I tell you it is hard, exacting and patient work to hunt egrets,’ Bennett told The Sun, boasting of his part in the near annihilation of egrets in his 20-year career. He had already ‘cleared out’ Central America with his team of shooters, moving on to the Gulf of California and now the Pacific Ocean side of Mexico, where he hoped there were just enough birds to keep him going until retirement in a few years’ time.

3. A PROTEST AT A ‘MURDEROUS MILLINERY’

A bird of prey by Edward Linley Sambourne: Punch magazine, 1892

A bird of prey by Edward Linley Sambourne: Punch magazine, 1892

Did anybody care? Judging by the fashion magazines and society portraits of the era, one might think not. But a handful of women were very angry.

In 1903, when an ounce of egret feathers could fetch $32 – almost twice as much as an ounce of gold – they launched a hard-hitting attack on consumers. This guerrilla marketing campaign, the first of its kind, was the work of the all-female Society for the Protection of Birds (today’s RSPB). Founded in 1889 in protest at the fashion for ‘murderous millinery’, the society now had 154 branches throughout Britain.

Spearheading their campaign was Etta Lemon, then aged 43, acerbic, single-minded and – I think – on the autistic spectrum. Etta was fierce in her contempt for female followers of fashion of every class. ‘The only thing that can be urged on behalf of osprey wearing is that it is nowadays so thoroughly democratic,’ she wrote witheringly, pointing out its popularity with charlady and duchess alike.

Campaign tactics were drawn up by co-founder Eliza Phillips, an 80-year-old rector’s widow. She was outspoken, articulate and infuriated by society women seen in opera boxes wearing hair ornaments ‘exactly like the sort of brush servants use to clean lamp-chimneys’.

4. THE CASE OF REAL... OR FAKE?

Young Etta Lemon / The Lemon family archive

Young Etta Lemon / The Lemon family archive

Etta and Eliza mobilised their 154 branch secretaries across the Britain. They were told to infiltrate stores, surprise shoppers, question shop girls, cross-examine head milliners and lecture shop managers. The ‘Frontal Attack’, as it was called, took place in springtime 1903: hat-buying season.

It was an excruciating mandate for these genteel foot soldiers of the (R)SPB, as ladies of fashion did not like to be caught ‘red-handed’ (so said Miss Conyers, branch secretary for Ilkley). It was a matter requiring ‘extreme tact’. But her objections were batted away. Red-handed these women must be caught.

Smooth-talking millinery saleswomen were also in their sights. Since the Society

had stepped up its anti-osprey campaign, real egret and heron plumes were now being peddled by the fashion industry as fake. Women with a conscience were

being sold these ‘fakes’ as an ethical substitute, just as you might buy an imitation

fur coat today.

It was claimed that fake ospreys were made from horsehair, or whalebone, or bleached grasses, or goose feathers steeped in acid. Each branch secretary carried a magnifying glass to examine samples at the counter. They would also buy samples and send them in to headquarters, where expert male ornithologists would have them forensically examined.

In each case, they were proven to be the real thing. It all made for great newspaper copy.

5. VIRGINIA WOOLF WAS INCENSED

The sandwich board parade: © RSPB

The sandwich board parade: © RSPB

How hard was it to prick the conscience of the Edwardian woman of fashion?

In 1911 sandwich board men paraded photographs of starving egret chicks through the West End. Fashion icon Queen Alexandra publicly renounced the ‘osprey’.

Lady mayoresses purged their wardrobes at the behest of Etta Lemon. But still the fashion persisted, even throughout World War I.

And then one modern voice stepped into the debate, with dazzling effect.

In 1920 Virginia Woolf was piqued by an article condemning not the hunters, but the heartless wearers of the snowy egret plumes.Women were to blame? Woolf was enraged. It made her want to ‘go to Regent Street, buy an egret plume, and stick it – is it in the back or the front of the hat? – and this in spite of a vow taken in childhood and hitherto religiously observed’.

Her point was this: ‘The birds are killed by men, starved by men, and tortured by men – not vicariously, but with their own hands.’ Men, too, were responsible for squashing the Plumage Bill, put before the House of Commons in 1920 for the fourth time. But, triumphantly, one year later it was finally pushed through by Nancy, Lady Astor: the first woman to take a seat in the House of Commons.

TESSA’S TOP TIPS

1. Go osprey feather spotting. The ‘osprey’ can be spied in many museum fashion collections, including:

- V&A (where anyone can ‘order’ hats online, to view at the Clothworkers' Centre)

- Brighton Museum

- The Museum of London

- The sumptuous Bassano photographic archive, held by the National Portrait Gallery, enables you to admire period beauties wearing the contested osprey, from Gaiety Girls to debutantes.

2. Good reads:

- Discover the fashion imperatives for an Edwardian upper-class woman by exploring the wardrobe of debutante Heather Firbank in London Society Fashion 1905–1925: The Wardrobe of Heather Firbank by Cassie Davies-Strodder, Jenny Lister and Lou Taylor (V&A Publishing, 2015). All her hats are available to view.

-

I explored the fascinating full story of the RSPB’s early years as an anti-fashion campaign in my book Mrs Pankhurst’s Purple Feather: Fashion, Fury and Feminism – Women’s Fight for Change (Aurum Press, 2018).

3. An egret walk

- The little egret is now a frequent visitor to Britain’s shores. Walk the Egrets Way along the River Ouse to Lewes, in East Sussex, and see these enchanting white birds for yourself.

OUR EXPERT’S STORY

Journalist and social historian Tessa Boase spent three years uncovering the untold women’s story of the early RSPB for her recent book, Mrs Pankhurst’s Purple Feather: Fashion, Fury and Feminism – Women’s Fight for Change. She loves the detective work involved in resurrecting stories of ordinary people – shop girls, milliners, campaigning housewives, Edwardian shopaholics and more. Her first book, The Housekeeper’s Tale: The Women Who Really Ran the English Country House, investigated life below stairs.

Tessa studied English Literature at Oxford and Italian in Florence, before working for The Daily Telegraph for many years. She now combines writing with teaching and lecturing and lives in Hastings with her family. Her talks for The Arts Society include Secrets of an Edwardian shopaholic, Fashion, fury and feminism: women’s fight for change and The housekeeper’s tale: the women who really ran the English country house.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS INSTANT EXPERT EMAIL...

Why not forward this on to a friend who you think would enjoy it too?

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers, published every fortnight.

About the Author

Tessa Boase

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition