This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Become an Instant Expert on the history of the great British park

Become an Instant Expert on the history of the great British park

15 Apr 2020

One of the greatest ‘inventions’of the 19th century was the public park. Today, we all use them – and love them – but what do we actually know about them? Our expert, Arts Society Lecturer Paul Rabbitts, shares his knowledge.

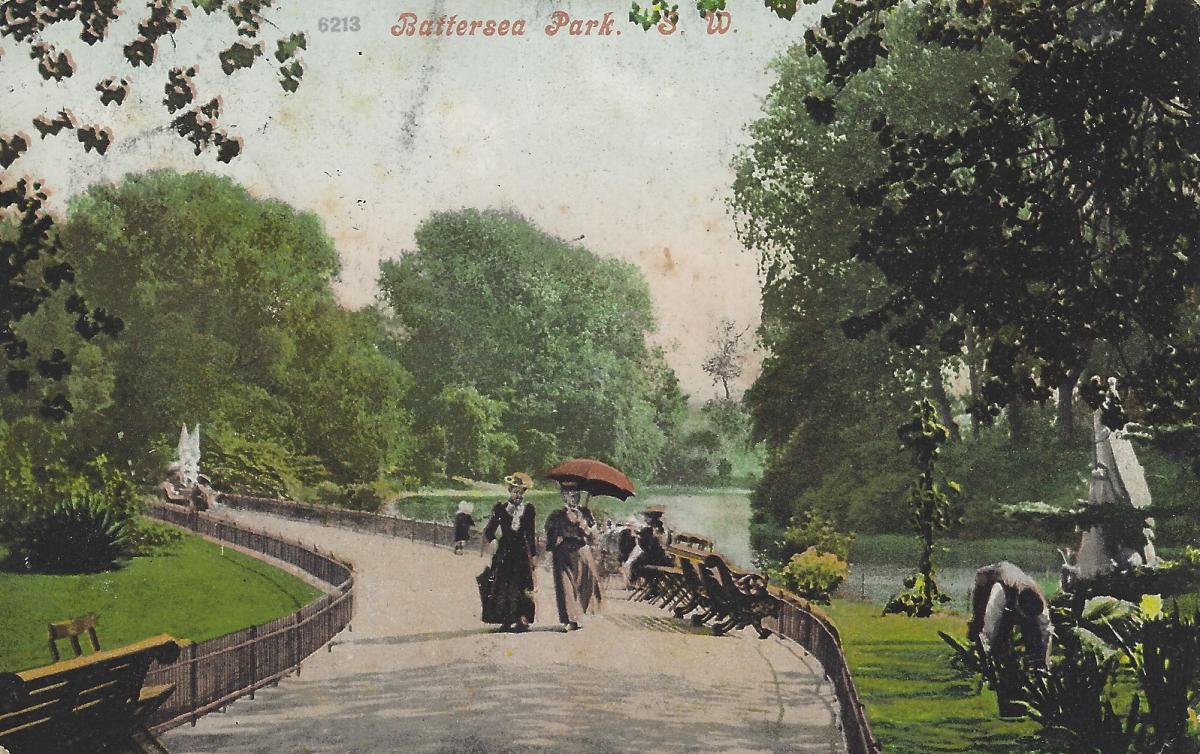

Battersea Park, London

Battersea Park, London

1.Great Britain has been a nation of park builders since the Industrial Revolution.

The garden designer, reformer and writer JC Loudon, writing in The Gardener’s Magazine in 1829, campaigned for public parks as ‘Breathing Places’ for towns and cities. London was the only city with parks – the Royal Parks – but these were mostly inaccessible, available only to royalty and those with special privileges. Indeed, some of these were not open to the public until the early part of the 20th century.

Along with the earlier pleasure gardens, such as Vauxhall Gardens in London, these parks were the earliest of prototypes for our great British parks. In the middle of the 18th century, the population was six million, with only one in five living in a town of any size. By 1851 the population was 18 million, with a 50:50 split between town and country. And by 1911 nearly 40 million (80%) were living in towns such as Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle, Leeds and Birmingham.

Moral concerns for the masses started in 1833, with the report of the Select Committee on Public Walks highlighting the benefit public parks could bring, and that ‘the provision of parks would lead to a better use of Sundays and the replacement of the debasing pleasures’.

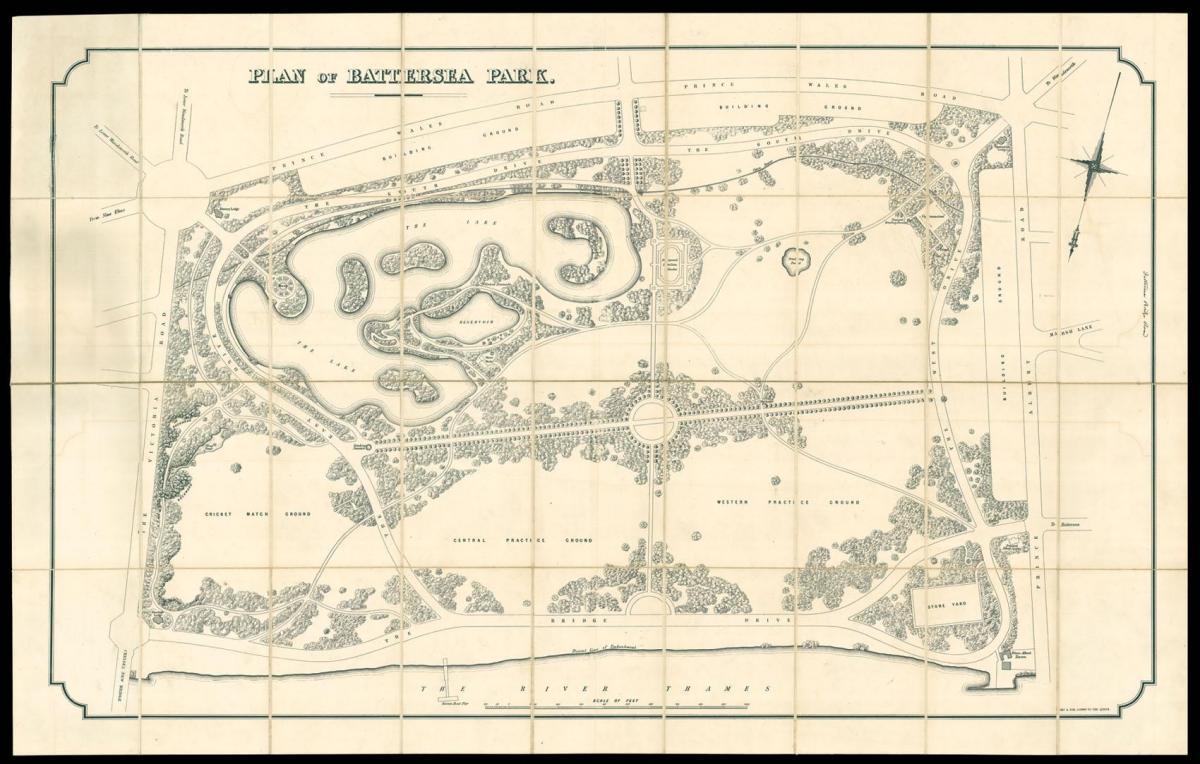

Battersea Park plan

Battersea Park plan

2. These were the movers and shakers

Among the key figures in the provision of public parks was the architect John Nash, who was responsible for the laying out of Regent’s Park, which was completed in 1825, as well as the remodelling of St James’s Park. Architect and planner James Pennethorne followed up with designs for Victoria Park (which opened in 1845) in the East End of London. He was architect to the Commissioners of Woods and Forests, and prepared an initial design that included a grand entrance, a perimeter drive with elegant housing, and a parkland landscape of trees and grass. Pennethorne was also involved in the design of Battersea Park, which opened in 1858.

It was, however, Joseph Paxton, gardener, designer, writer and creator of one of the most famous buildings of Victoria's reign – the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park – who had the greatest impact on British parks. Paxton was head gardener at Chatsworth and was commissioned by the Birkenhead Improvement Commissioners – the town being the first to apply to Parliament for powers to use public funds to create a municipal park.

Birkenhead Park was opened on 5 April 1847 and was the inspiration for the greatest park in the world – Central Park, New York. Those that worked for Paxton became great designers in their own right – Edward Kemp, Edward Milner and John Gibson. And those that followed included the municipal park superintendents who gave us many of our most important parks – JJ Sexby (London), William Pettigrew (Manchester and Cardiff) and Captain Sandys-Winsch (Norwich).

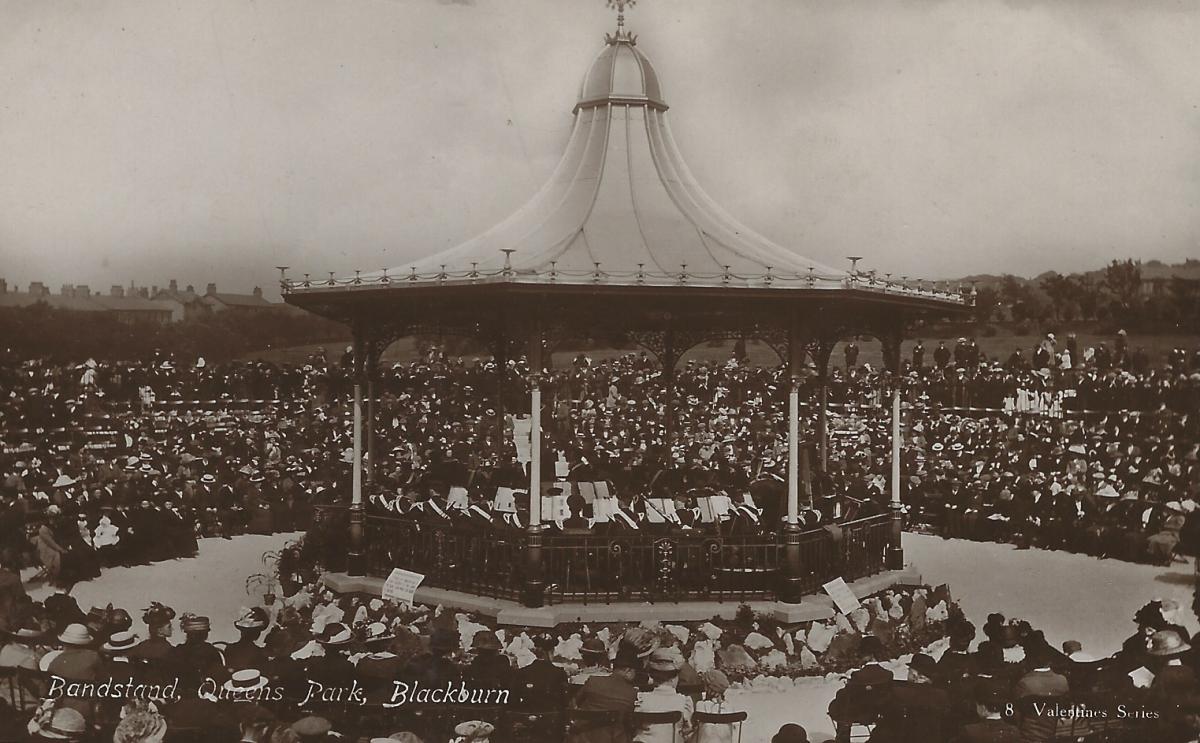

3. It’s ‘parkitecture’ that makes a great park

When I say ‘parkitecture’ I’m thinking of statues, and drinking and ornamental fountains; ornate gates, shelters and benches; cafés, aviaries, park lodges and palm houses; and toilets, lidos, paddling pools, play areas and sports facilities. I’m also thinking of clocks and war memorials. The most iconic element of all ‘parkitecture’ though was the bandstand – no park was complete without one. From simple rustic structures to cast-iron masterpieces of engineering, bandstands dominated parks from the 1880s to the beginning of World War II.

The music that emanated from them ranged from the sounds of military bands and brass bands to, later, popular dance bands. Crowds of 10,000 or more were not unusual, and on one occasion in 1861, in Corporation Park, Blackburn, over 50,000 people turned up to listen to 11 brass bands. Latterly, groups such as Fleetwood Mac, Pink Floyd, the Bay City Rollers, Dire Straits, the Rubettes and Led Zeppelin all performed on a bandstand. Last year the bandstand in Beckenham where singer David Bowie organised, and performed at, a festival 51 years ago was given Grade II listed status.

Paisley Gardens fountain, Glasgow – pre-restoration

Paisley Gardens fountain, Glasgow – pre-restoration

4. Parks went into a decline…

Post World War II, the decline of public parks began, despite efforts to make them more open for sport and recreation. By the 1970s and early 1980s, the rot had truly set in, with antisocial behaviour being seen. Some parks became no-go areas. Compulsory competitive tendering with contractors – when local authorities had to test the market with contractors regularly, at times at the cost of quality – ripped the heart out of our 27,000 public parks. Lidos closed, bandstands were removed, palm houses demolished, flower beds disappeared and parks departments were disbanded.

Parks were born out of the need to improve the quality of people’s lives as the Industrial Revolution took its hold. One hundred years later, this was abandoned as we embraced ‘the cost of providing’ rather than the ‘benefits [note the plural] of providing’, only to rediscover this by the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century.

Paisley Gardens fountain, Glasgow – restored

Paisley Gardens fountain, Glasgow – restored

5. …but we still need them

Thanks to successive studies and reports, surveys, analysis and continued lobbying, many parks have been rescued from virtual obscurity, funded primarily by the National Lottery. The irony is perhaps wrapped up in the past – history tells us that parks are good for us.

In 2014 and 2016, the Heritage Lottery Fund published two reports on the condition of parks in the UK. The picture was once again bleak. Funding for public parks and urban green spaces was significantly reduced between 1979 and 2000, with an estimated cut of £1.3bn in total. And from 2018, some councils had up to 90% cuts in their annual budgets.

Yet a timely report published in January 2013 by the International Federation of Parks and Recreation Administration (ifpra.org) had concluded that there is evidence for benefits of urban parks, and that there is sound scientific evidence that they contribute to human and social wellbeing – more important than ever today.

In 2015, 186 years after JC Loudon’s pleas, The Times reported that ‘it’s mad to let Britain’s glorious heritage of urban parks disappear’. Speaking at the Paxton 150 conference in 2015, parks historian David Lambert echoed this: ‘What Paxton and his fellow Victorians thought was obvious – that the health, social and recreational benefits of parks far outweigh the costs of maintaining them.’

As those of us who love our parks would proudly say on social media – in true 21st-century fashion – our #parksmatter.

Paul’s top tips

For three great examples of parks, head to:

- Birkenhead Park on the Wirral, Paxton’s masterpiece of design

- Richmond Park, a former royal hunting ground that has hardly changed over the centuries

- Glasgow Green, with its incredible Winter Gardens and washing lines – still used to this day

And for a good read, there is Paul’s book: Great British Parks – A Celebration, published by Amberley Publishing

Our expert’s story

Paul Rabbitts is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a Fellow of the Landscape Institute and a qualified landscape architect and head of parks, heritage and culture for Watford Borough Council, who has worked in parks for over 30 years. He is a national authority on the Victorian and Edwardian bandstand. Among his fascinating talks are Great British Parks, London’s Royal Parks and Bandstands – History, Decline and Revival.

Stay in touch with The Arts Society! Head over to The Arts Society Connected to join discussions, read blog posts and watch Lectures at Home – a series of films by Arts Society Accredited Lecturers, published every fortnight.

About the Author

Paul Rabbitts

Article Tags

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition