This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

The things Lemn Sissay told us

The things Lemn Sissay told us

1 Mar 2024

Confessions, hard knocks and writing at dawn: Sue Herdman meets award-winning poet, author and broadcaster Lemn Sissay

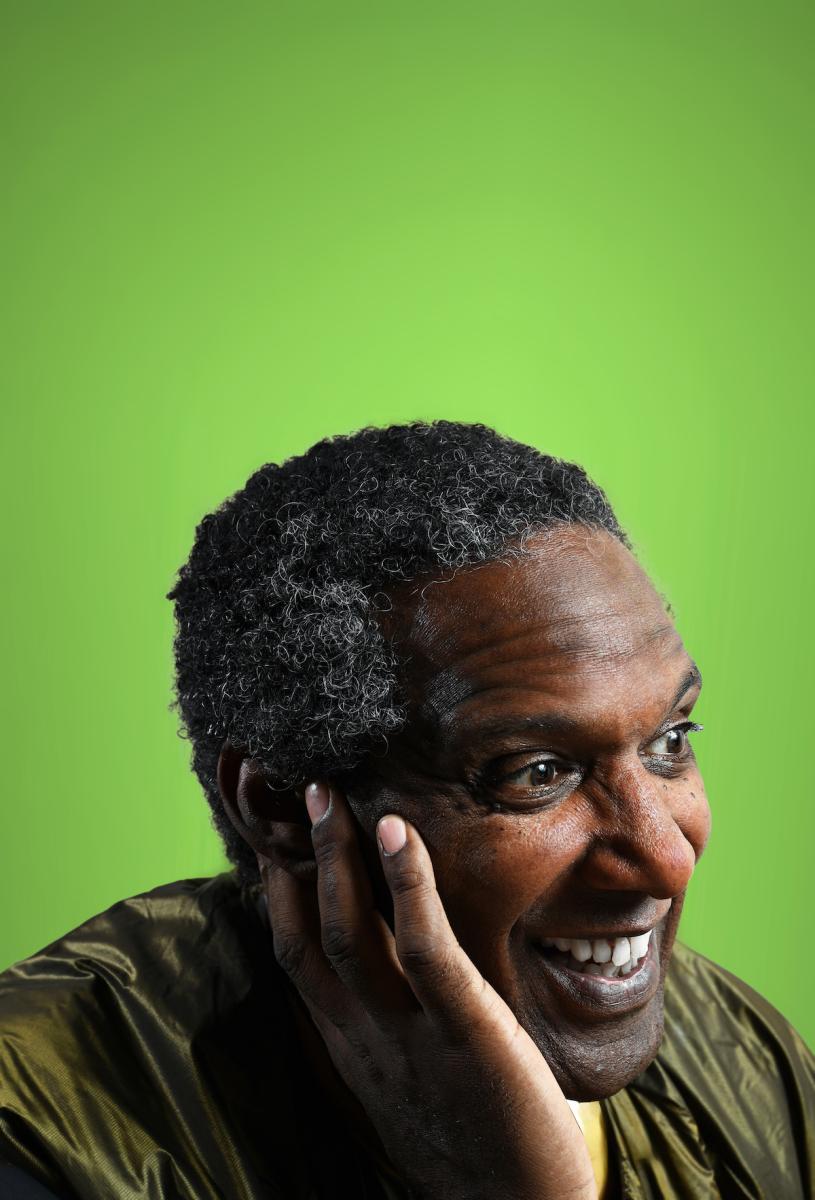

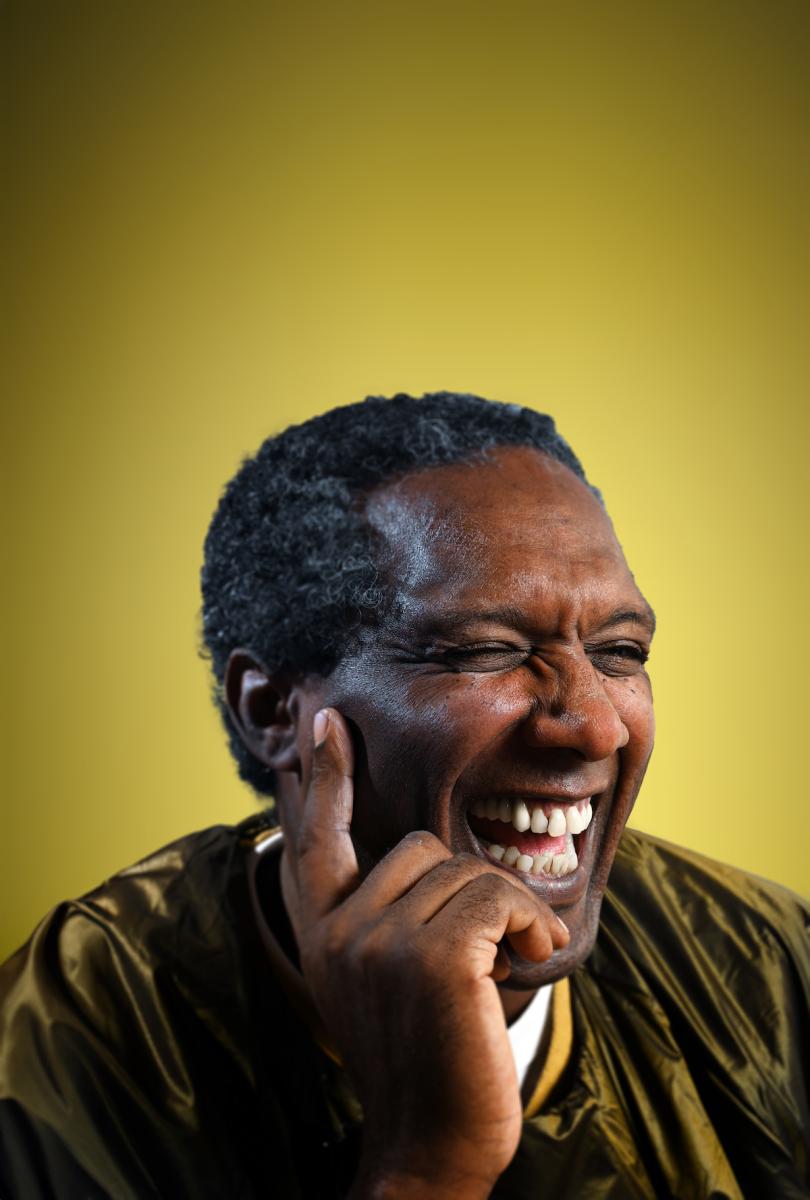

Lemn Sissay photographed in East London for The Arts Society Magazine by John Millar

Lemn Sissay photographed in East London for The Arts Society Magazine by John Millar

Lemn Sissay’s story, once heard, is not to be forgotten.

His memoir, My Name is Why, outlines his tale. He was born in 1967 to a beautiful Ethiopian student, alone in Britain on an academic scholarship. As a baby Sissay was transferred from the mother and baby unit in Wigan, where she had been sent, to a local foster family. He was a part of that family for 12 years until rejected and placed in the care system. There he was buffeted between facilities, each one increasingly less appropriate for a fiercely bright child who had done nothing wrong, and had no one around who looked like him.

It should have been so different. When he came of age, an empathetic social worker gleaned his birth certificate. That’s when he discovered his true name. And it’s when he saw the letter his mother Yemarshet had written the year after his birth, asking the authorities what steps she should take to get her child back. Her request came to nothing; the authorities deemed her child’s current path a satisfactory one.

It’s the story, essentially, of a stolen childhood.

Against all odds, Sissay navigated his way up and out. From his gutter-cleaning business as an 18-year-old, his first flyer proclaiming his services in verse, he is now internationally known. He’s an honorary doctor at numerous universities; a former chancellor of Manchester University; an OBE and a trustee of the Foundling Museum. His Landmark poems can be seen in London, Manchester and Addis Ababa. In 2023 he was given the Freedom of the City of London.

His most recent work, Let the Light Pour In: Morning Poems, is the result of a sunrise ritual. For 10 years, as day breaks, Sissay has written a stanza of four lines. These works have gone on to appear in murals, be sung as songs and inked on skin. Just like their creator’s story, their messages can stop you in your tracks.

We meet over coffee in an east London café. These are the things he told me…

Lemn Sissay photographed by John Millar

‘The dawn quatrains started incrementally’

‘I was enticed by the idea of saying something in four lines that hadn’t been said before. The concept teased an energy out of me. The pursuit of originality through imagination. And that goes back to when I started to write as a child. I sensed a new world that tapped into who I was. I was lost, but in writing I found an essential part of me. I was tapping a truth, like tapping the sap from a tree.’

Admissions and echoes

He pens his morning lines, then sends them on their way on social media. And here’s a confession you don’t hear often from figures of Sissay’s standing: ‘Some are good. Some are terrible! And that’s OK!’ He writes them, he reveals, in lieu of having a family. ‘If nobody read them I’d still do them. They are a record of what I was doing and where I was on that day.’ With no family you have no childhood references, no familial witness to your recollections or, as Sissay puts it, ‘no echo’.

Sissay is an advocate for therapy…

…but he’s adamant art isn’t a cure. ‘I don’t think of art as therapy in itself. That would belittle therapy. But what is art in the context of therapy? Now that’s interesting. Art can be a home to go to. A reference: you know where you were and who you were with when you clocked, say, a seminal painting, because there was an emotional and physical state connected to that experience. Elements coming together are important for memory. In my childhood, memories of place and time and emotions were taken away. But when you engage with art you get all those. That’s what happens when I write. When I went into care I wrote poems to anchor me. To help remind me I was from somewhere. Imagine being lifted up in a hurricane. If you keep your eye on one spot somehow you are relative to a place. That’s what poetry did for me. I could describe the whirlwind, the objects and people being scattered, and where I had come from emotionally.’

Every child’s right

So what of those who experience ‘threshold anxiety’ – a daunting sense that a grand arts space is not for them? Sissay is fired up: ‘We have to ensure we’re more focused on the self-esteem of the individual, the child, than we are on the self-esteem of the institution. They need to be asking: how can we empower an interest in art in children? Our museums and galleries are full of radical ideas and diversity the young should be exposed to. Every child deserves to have their favourite gallery.’

Lemn Sissay photographed by John Millar

Don’t ring-fence creativity

Sissay is resolute on another matter. ‘Poetry,’ he tells me, fixing me with his grin, ‘is not a minority sport. Nor is creativity! That’s everywhere. It’s at the heart of what it is to be human. It’s not the monopoly of artists. Think of the high street hairdressing salon. People think it’s utilitarian. Yet we go and get transformed internally and externally. We sit gazing at a portrait of ourselves, while our hair is sculpted and stories are shared. It’s a life force to plug into.’

What the stage means to Sissay

‘I have such respect for that moment on stage. I don’t like that “them and us” nature of performance. That “I speak, you clap” thing. It’s ungenerous. And untruthful. The stage is a place for truth.’

Tips for young artists

The young Sissay questioned why he was choosing to go into the literary world: ‘It’s so damn

small.’ But, silver linings. ‘We talk about having to smash down walls in the arts,’ he says, ‘but a lot of those are imagined. There is support. I felt it from bodies like the Arts Council. Had they not supported the libraries and theatres and small Black publishing houses that then supported me, I couldn’t have got going. So, seek out support. Find your tribe. Listen

to your imagination. Stop being hurt. Remember: if it were not imagined, it could not be made, thus imagination must not be afraid.’

‘I view myself as…

…a poet, a northerner, a collection of molecules, a British Ethiopian, a Black man, an artist activist… but mostly a poet.’

Find out more

• Let the Light Pour In: Morning Poems by Lemn Sissay is published by Canongate

• See lemnsissay.com

• Lemn Sissay is founder and trustee of The Gold from the Stone Foundation, which supports the Christmas Dinner project that works to ensure no care leaver is alone at Christmas; find out how to get involved at goldfromthestone.org.uk

Read

Discover the poems Lemn Sissay turns to, the performance he won’t forget, the item he collects and more in Sue Herdman’s full interview with the poet in the latest issue of The Arts Society Magazine, out now and available exclusively to members and supporters of The Arts Society (to join, see theartssociety.org/member-benefits)

About the Author

Sue Herdman

is an arts and culture journalist and Editor of The Arts Society Magazine

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition