This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

William Blake’s Wild World

William Blake’s Wild World

2 Oct 2019

Tate Britain has opened its seminal show on that radical Romantic, William Blake. Three Arts Society Lecturer experts – Elizabeth Merry, Justine Hopkins and Tim Stimson – are here to tell you more about the man whose art burned bright.

‘You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough’ William Blake (1757–1827)

Tell us something we might not know about Blake

Elizabeth Merry: Between 1800 and 1803, Blake moved into a cottage in the village of Felpham with his wife, Catherine. A brief sojourn in the Sussex countryside changed his outlook on his work. The surrounding pastoral and coastal landscapes encouraged Blake to become more self-aware, which had a profound effect on his art and poetry.

Justine Hopkins: Extraordinarily, Blake taught himself to write backwards. This allowed him to print his poems as complete plates, with text and image interwoven, rather than printing the words first and adding the illustrations afterwards – as was usually done.

Tim Stimson: It seems ironic that Blake’s most widely known (though probably least understood) poem, Jerusalem, was discarded by him as the preface for his prophetic book Milton – an epic poem based on the life of the Renaissance writer. In 1916, Sir Hubert Parry set the poem to music, transforming it into the famous hymn we know today.

'Europe' Plate i: Frontispiece, 'The Ancient of Days' 1827. The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

'Europe' Plate i: Frontispiece, 'The Ancient of Days' 1827. The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

What fascinates you about Blake?

EM: His inventiveness. Blake created an entirely new form of engraving, called ‘illuminated printing’, which allowed him to print his poems and illustrations in one printing process. Instead of scratching an image onto a waxed copper plate, Blake would draw his poems and pictures on the plate in an acid-resisting paint. This was made out of candle grease and salad oil. He then immersed the plate in acid, which ate away the unprotected parts so that the design would stand out and prints could be taken. The Songs of Innocence and of Experience are the best-known examples of this technique.

JH: When Blake was commissioned to illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy, he taught himself Italian in order to ‘get the feel’ of the author in his original language. I find his dedication to his work inspiring. All his prints were finished by hand, and it is thanks to him that printmaking became accepted as a creative discipline.

TS: I find Blake’s emphasis on the power of ‘mind-forged manacles’ – the idea that our limitations are self-imposed – particularly insightful.

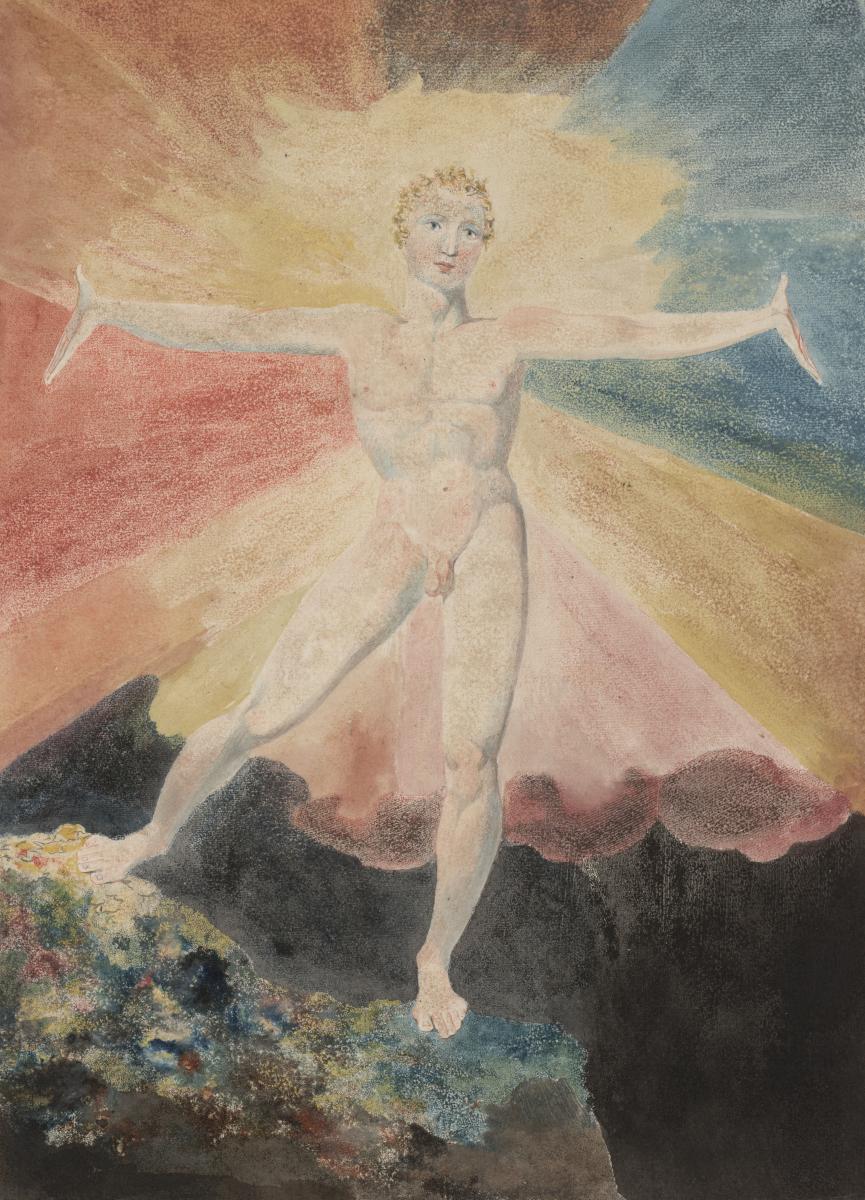

Albion Rose c. 1793, colour engraving, courtesy of the Huntington Art Collections

Albion Rose c. 1793, colour engraving, courtesy of the Huntington Art Collections

What is your favourite work by Blake?

EM: One of his most inspiring paintings is the one variously known as Glad Day or The Dance of Albion. It is a joyous and colourful vision of a naked human figure – exultant and free, divested of class, politics, injustice and poverty.

JH: Too much choice! But I particularly love a small painting on copper in the V&A’s collection called Eve Tempted by the Serpent. Because it is painted on copper the colours have lasted better than many of his works: the sky over Eden is the deepest azure blue imaginable, with a new moon touched with gold glinting in the sky above a waterfall plunging into a river. In the foreground is an enormous tree, its branches curving across the picture like the lintel of a great arched door.

TS: My favourite work is Glad Day or The Dance of Albion. It is an image that represents a truly liberated humanity, which Blake draws on in his poetry and pictures.

‘No bird soars too high if he soars with his own wings’ William Blake

Jerusalem, plate 28, proof impression, top design only 1820; relief etching with pen and black ink and watercolour on medium, smooth wove paper, Yale Center for British Art (New Haven, USA)

Jerusalem, plate 28, proof impression, top design only 1820; relief etching with pen and black ink and watercolour on medium, smooth wove paper, Yale Center for British Art (New Haven, USA)

The Blake timeline

- 1757: William Blake was born in Soho, London, into a family of Nonconformists. His father was a haberdasher and hosier

- 1772–79: Blake was apprenticed to engraver James Basire and made engravings of the monuments of Westminster Abbey

- 1780: he first exhibited at the Royal Academy

- 1782: the artist married Catherine Boucher; she became a vital presence and support to him throughout his turbulent life

- 1799: the artist received his first commission from the man who became his chief patron, Thomas Butts, who was, according to Blake’s first biographer, ‘the only large buyer the artist ever had’. Butts was the chief clerk to the Commissary General of Musters (the department responsible for military pay)

- 1818: meets his second most important – and last – patron, John Linnell, a successful artist

- 1827: Blake dies in the city he was born in, London, and was buried at Bunhill Fields

Elizabeth Merry, Justine Hopkins and Tim Stimson are Accredited Arts Society Lecturers. For more information about their range of talks, visit elizabethmerry.wordpress.com, justinehopkins.wixsite.com and timstimsonarts.co.uk

SEE

William Blake, Tate Britain

The largest exhibition of Blake’s work for 20 years brings together more than 300 original artworks, including watercolours, paintings and prints.

Until 2 February 2020

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition