This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Understanding the Power of Printmaking

Understanding the Power of Printmaking

6 Dec 2021

Billie Muraben considers the egalitarian artform that has shaped both contemporary art and popular culture, as a new exhibition opens at Pallant House Gallery

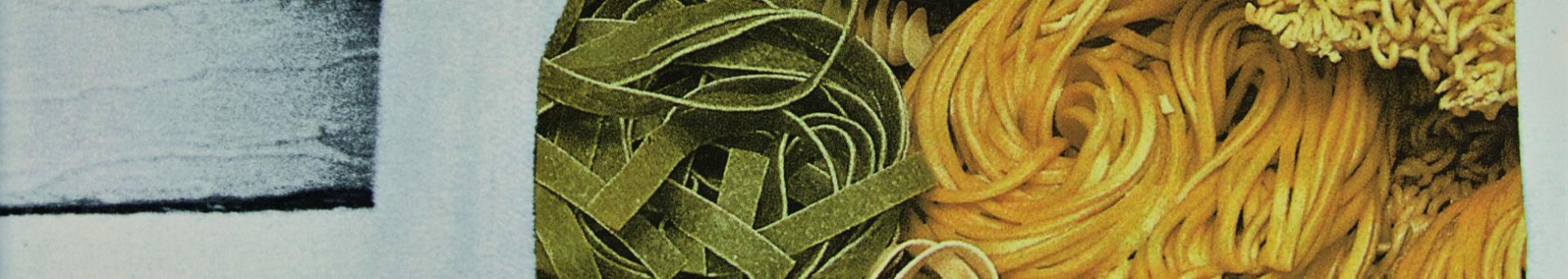

Anthea Hamilton, Manarch (Pasta), 2013, Screenprint on paper, © Anthea Hamilton (courtesy Thomas Dane Gallery)

As Britain emerged from its post-war years, broad social change — impacted by the shift in government, through uprisings, developments in technology and popular culture — led to major changes in the practice and dissemination of contemporary art.

Printmaking had previously been relied upon for producing editions of existing works, making books, or generally pointing to a storied ‘original’. The technique dates back to 800AD, when wood blocks were first chiselled with text in China. Nowadays, images are produced by cutting into and inking plates for relief printing; scratching and incising with acid in intaglio; through the repulsion of oil and water in planographic printmaking; and with the use of stencils and silk screens in serigraphy.

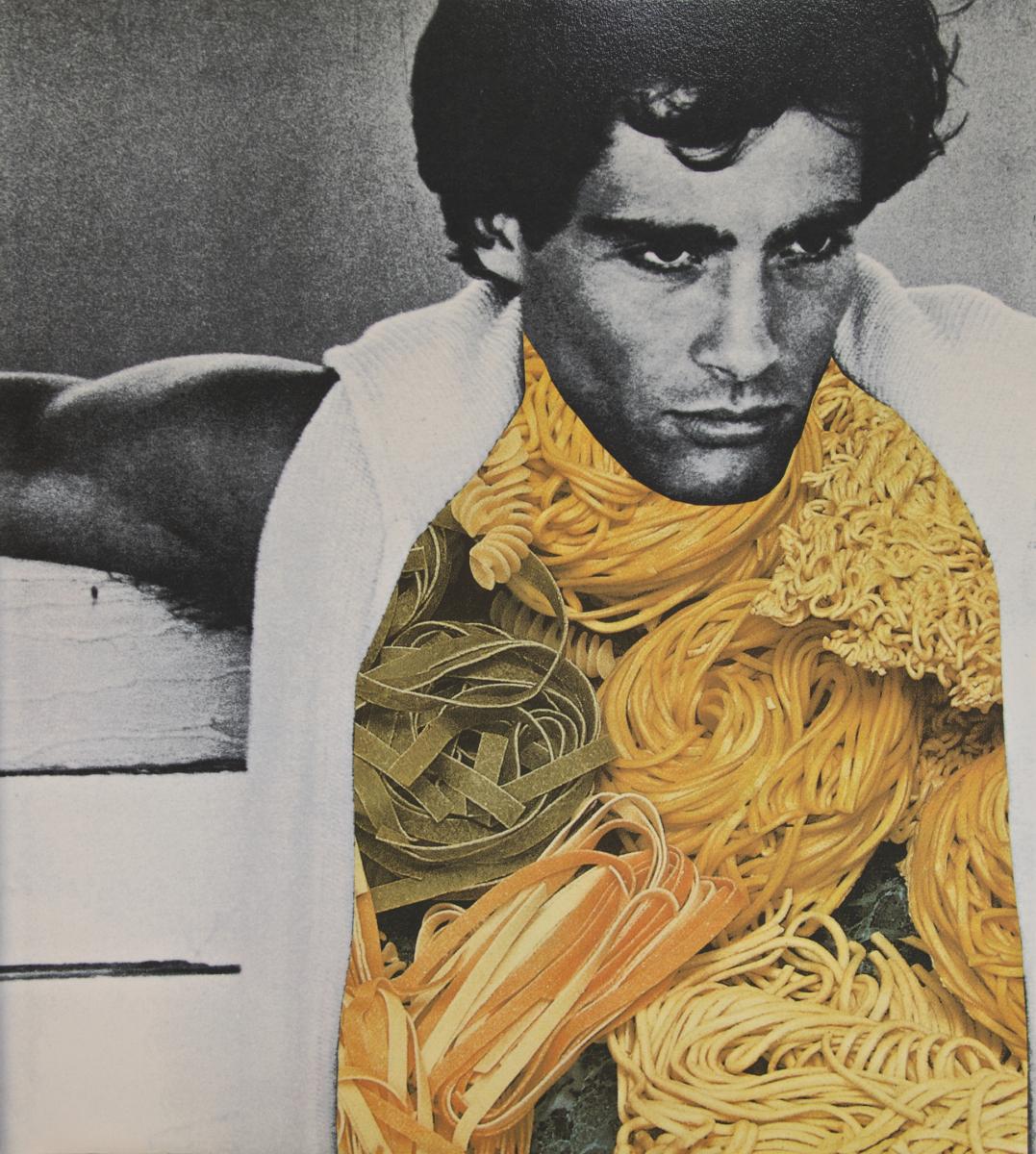

Chris Ofili, Afro Harlem Muses, 2005, Lithograph with embossment on paper © Chris Ofili (courtesy Victoria Miro, London)

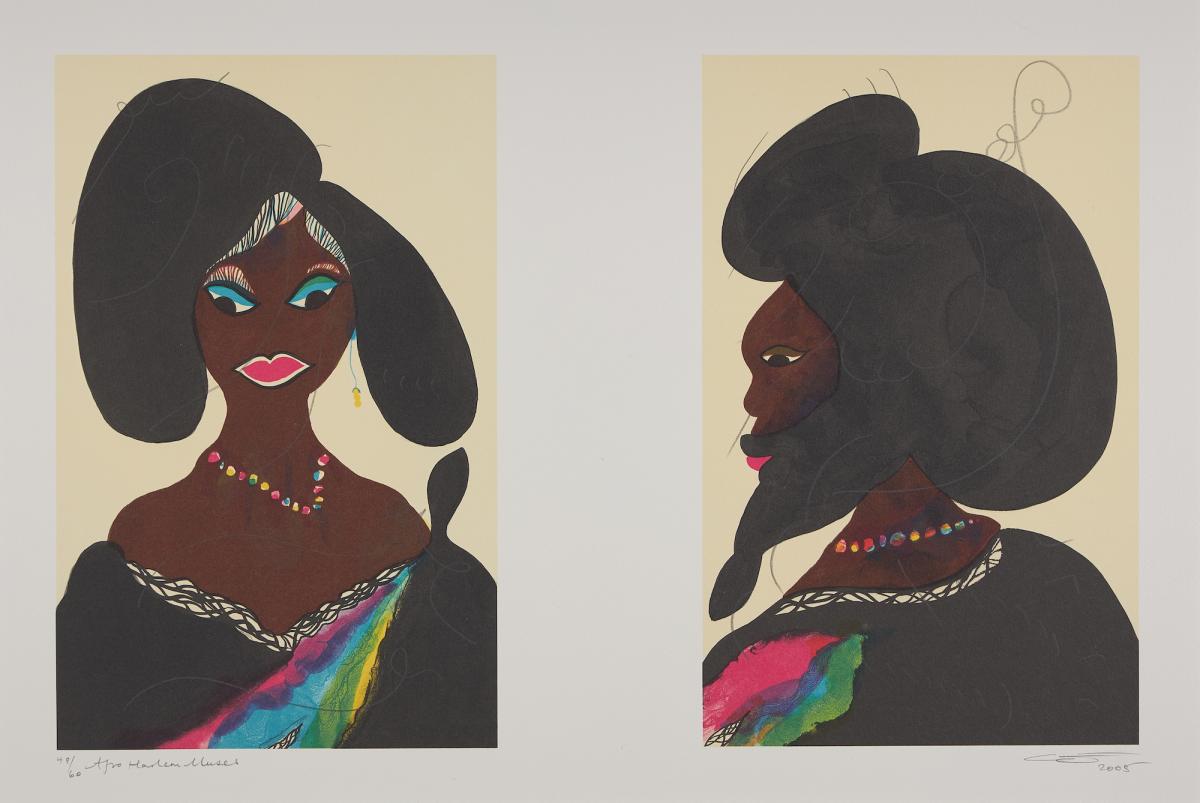

While editions remained popular, in the 1960s printmaking became a practice more widely adopted by contemporary artists, who learnt the specialist medium through collaborations with technicians who worked in studios or at colleges. While studying for his Masters at the Royal College of Art, David Hockney produced Kaisarion with All his Beauty (inspired by the poems ‘Alexandrian Kings’ and ‘Kaisarion’ by CP Cavafy), an etching that is layered in both process and meaning. Taking an experimental approach, he utilised dry-point, aquatint, black and red ink, and a metal stamp of the royal crest to depict Kaisarion, the son of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra, atop a cloaked figure, who stands beside a portrait of Hockney’s mother, stylised to mimic depictions of the Egyptian queen.

David Hockney, Kaisarion with All His Beauty, 1961, Etching and aquatint on paper, © David Hockney

The print is in the first room of Pallant House Gallery’s Hockney to Himid: 60 Years of British Printmaking. The exhibition chronicles the wide-ranging techniques, themes and potentials of printmaking, showing us why it continues to inspire artists, both elevating the status of the process and continuing to democratise access to art. While the show officially chronicles a 60-year period, it opens with an important prelude, through the practices of artists including Enid Marx, John Piper and Julian Trevelyan, who had been part of a generation of practitioners who sought to bring art to the masses, seeing the potential of print and its relation to the public, installing works in pubs, schools, and stations across the country.

The intention was to provide quality contemporary works for the education of children, reflecting the optimism of modernity through subjects they could understand

In the 1940s, School Prints — established by arts campaigner Brenda Rawnsley and her husband Derek — produced a series of lithographs with Baynard Press, which were available to primary schools on a subscription. The intention was to provide quality contemporary works for the education of children, reflecting the optimism of modernity through subjects they could understand, with prints by John Nash, Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Commercial print studios, like the Curwen Press, opened fine art subsidiaries, and artists worked with technicians and independently, to produce editions and original works in print. The renewed interest led to a change in the boundaries between commercial and fine art practice, with print becoming a vital medium within the realm of contemporary art.

From Hockney to Himid carries through this progression, with attention given to Pop art and its integral challenge to authority. Patrick Caulfield’s Ruins is a key example, having caused controversy on its inclusion in the Paris Biennale, 1965, on the objection that it had been printed by a technician rather than the artist.

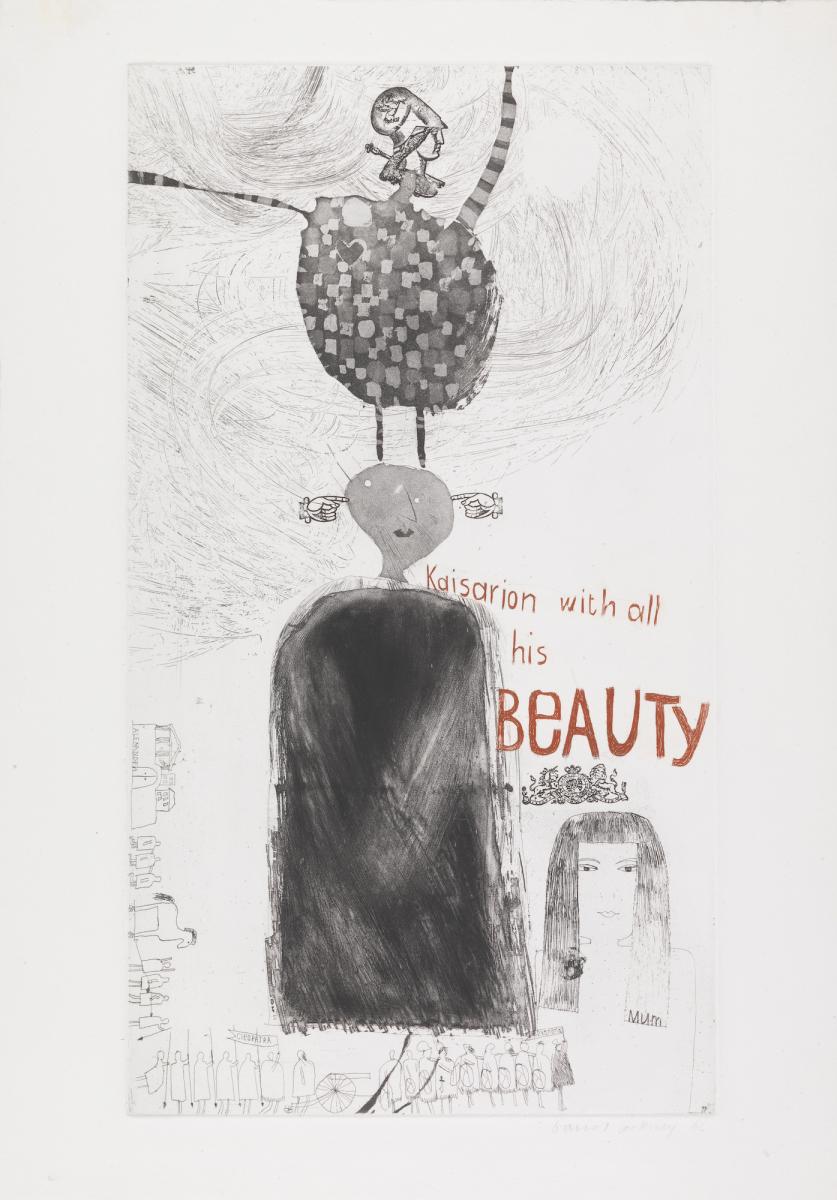

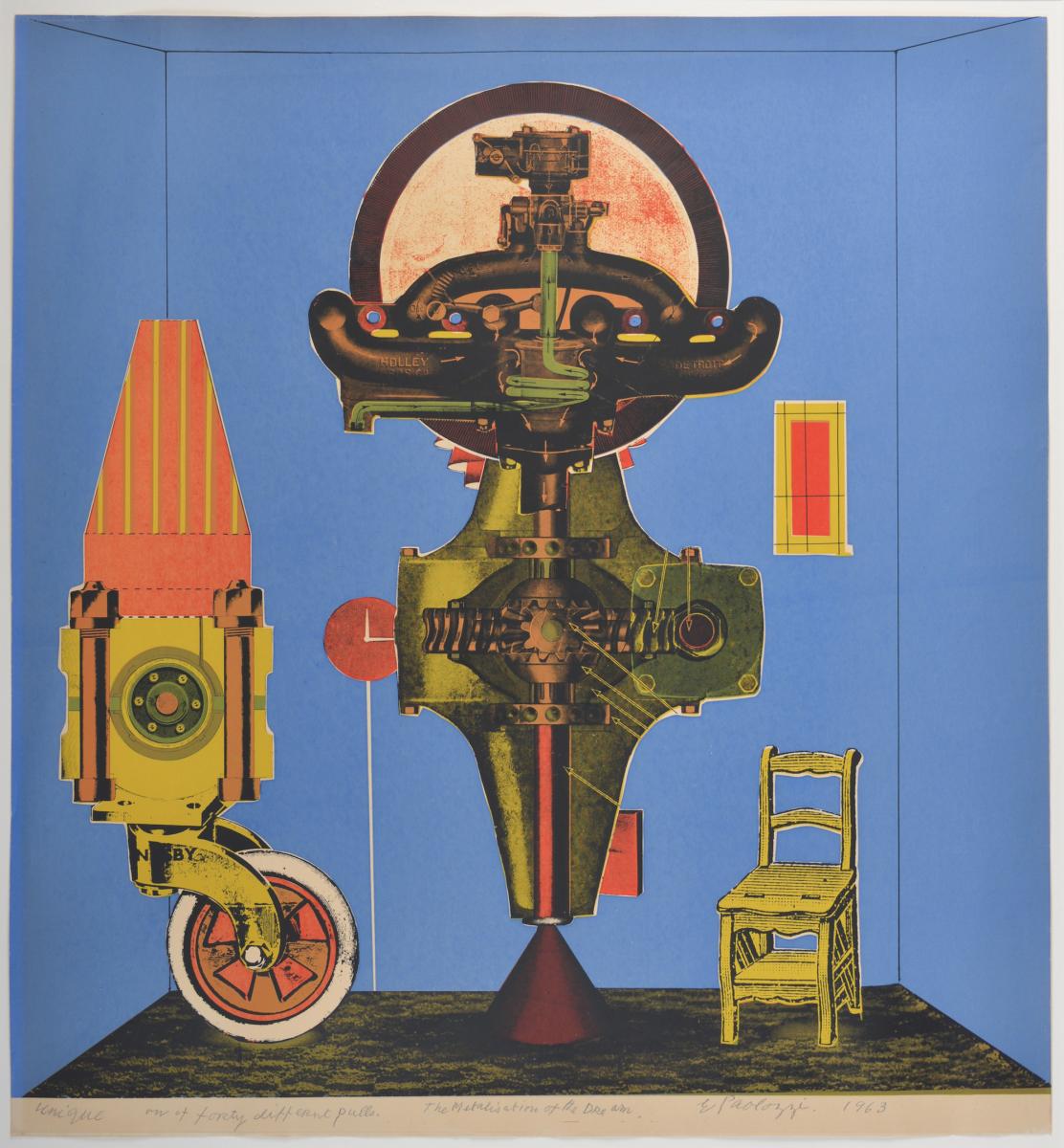

Eduardo Paolozzi, Metalization of a Dream, 1963, Screenprint on paper, © The Paolozzi Foundation, Licensed by DACS 2021

Undoubtedly, printmaking relies on the purposeful imprint of the human hand, and it can also carry meaning through its materials, and the context in which it was made. Through the practice of depicting landscapes and cities, collective histories and private moments, prints capture a moment in time in a way that feels more involved than a photograph, but retains a sense of immediacy and reaction.

Emma Stibbon’s Eldfell Heimaey, White House, makes use of ash from the volcano that sits at the back of the print landscape; Ciara Phillips’ A Lot of Things Put Together (Sophie) was made as part of an immersive installation, where the artist invited people to make collaborative prints with her. Each element, from the means of production to its context, adds to the layered significance of printmaking, all these parts coalesce when work interacts with a viewer.

Lubaina Himid, Birdsong Held Us Together, 2020, Lithograph on paper, © Lubaina Himid. Image courtesy the artist, The Hepworth Wakefield and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: David Lindsay.

As part of a new School Prints initiative by the Hepworth Wakefield, Lubaina Himid made a work in response to the restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Birdsong Held Us Together, which closes the exhibition. Himid says of her practice: “I think of my work the way I think of performance, theatre, or opera… it doesn’t really work unless an audience is exchanging something with me”.

SEE

Hockney to Himid: 60 Years of British Printmaking at Pallant House Gallery until 24 April

About the Author

Billie Muraben

Billie Muraben is a freelance arts and culture writer

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition