This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

THREADING THE TALE

THREADING THE TALE

13 May 2022

Arts Society Lecturer Susan Kay-Williams, curator of an embroidery show, unpicks the history of the medium, revealing a world of hidden messages, national pride and a movement to keep destitution from the door

Royal School of Needlework degree students today at Hampton Court Palace

The embroiderers of the British Isles have been at work a long time. The oldest extant object is thought to be St Cuthbert’s stole, made in the 10th century and placed in his shrine. The reasons for its survival are twofold: by being placed in the tomb, it was undisturbed until opened in 1827; and it is made predominantly of metal thread, which is far more resilient than linen or silk.

The Bayeux Tapestry, believed to have been made in England (some argue it might have been France), is probably the most famous embroidery although, with the name ‘tapestry’, it is frequently misunderstood. It is, in fact, a tour de force of wool embroidery with surface embellishment made from fine crewel wool. The colour would have come from the more varied hues of sheep’s wool at the time, as well as dyeing.

Elizabeth I in highly embroidered robes, courtesy Bridgeman Images

The highest form of hand embroidery came in the early Middle Ages. Known as Opus Anglicanum (OA), or ‘English work’, it was professional embroidery worked by both men and women. It featured rich ground fabrics such as Italian velvets, with adornment of gold threads. Specifically, the gold was actually worked through the fabric for each stitch in a technique called underside couching. This was time-consuming and expensive, but its glory was when seen in candlelight: the gold thread had multiple facets that would catch the light. So expensive was this work that only royals and the Church could afford it. Made in the City of London, it was in demand across Europe. The inventory of one Pope showed some 40 pieces.

An embroidered work called Faith and Fears, by RSN degree student Alex Standring

EXPENSE AND PROTEST

In addition to expensive goldwork the other hallmark of OA was what might be described as ‘personalisation’. The vestments made at this time were highly illustrative for an illiterate audience, telling Bible stories in pictures. Prior to this work, any people depicted on vestments were more like cut-outs, with little difference. If saints were shown the viewer had to work out who it was by their attribute, as they were not otherwise differentiated. (Each saint was given an attribute by artists, based on their life or martyrdom. For example, Saint Barbara is shown with a tower, indicative of her imprisonment.) With OA, each looked different with expressive faces and personality. The high cost of OA, unfortunately, ensured that in time it died out and, from the 15th century onwards, gold thread was instead laid flat on top of a fabric and secured in place with what is known as a couching stitch, with padding being used to give the thread more facets.

‘THE VESTMENTS MADE AT THIS TIME WERE HIGHLY ILLUSTRATIVE FOR AN ILLITERATE AUDIENCE, TELLING BIBLE STORIES IN PICTURES’

By the 16th century embroidery was both a professional occupation, mostly for men, and a domestic activity. Elizabeth I had a team of embroiderers to embellish her garments. There are portraits of her wearing gowns of blackwork, a technique where you see the outline of, for example, a flower in black thread, with the petals and leaves filled in with geometric patterns. This originated in Spain and its arrival in Britain is often credited to Katherine of Aragon, as she was known to have used it on the linens of Henry VIII (its introduction to Britain, however, predates Katherine, arriving around the late 14th century).

Henry’s first wife was not the only stitcher at court. While a princess, Elizabeth stitched a book cover for her stepmother Katherine Parr. And the most engaged royal stitcher was Mary, Queen of Scots who, with her ersatz gaoler, Bess of Hardwick, not only stitched pieces such as cushion covers, but created what could be called protest embroidery. In one of her panels Mary depicts a crowned ginger cat toying with a grey mouse, as an allusion to red- headed Elizabeth and herself. Other panels reveal her despair, with caterpillars devouring a rose.

RSN degree graduate Livia Papiernik’s spring-like embroidered project, The Lost Garden

HIGH STYLE

Another high point of British embroidery came in the 17th century, with work based on the Jacobean tree of life and, through the middle of the century, the embroidered caskets made by girls of 11 or 12, taking embroidery back into the domestic environment. In the 18th century the medium returned to a professional activity, with the development of silk shading, thanks to dyers being able to create more shades for each colour.

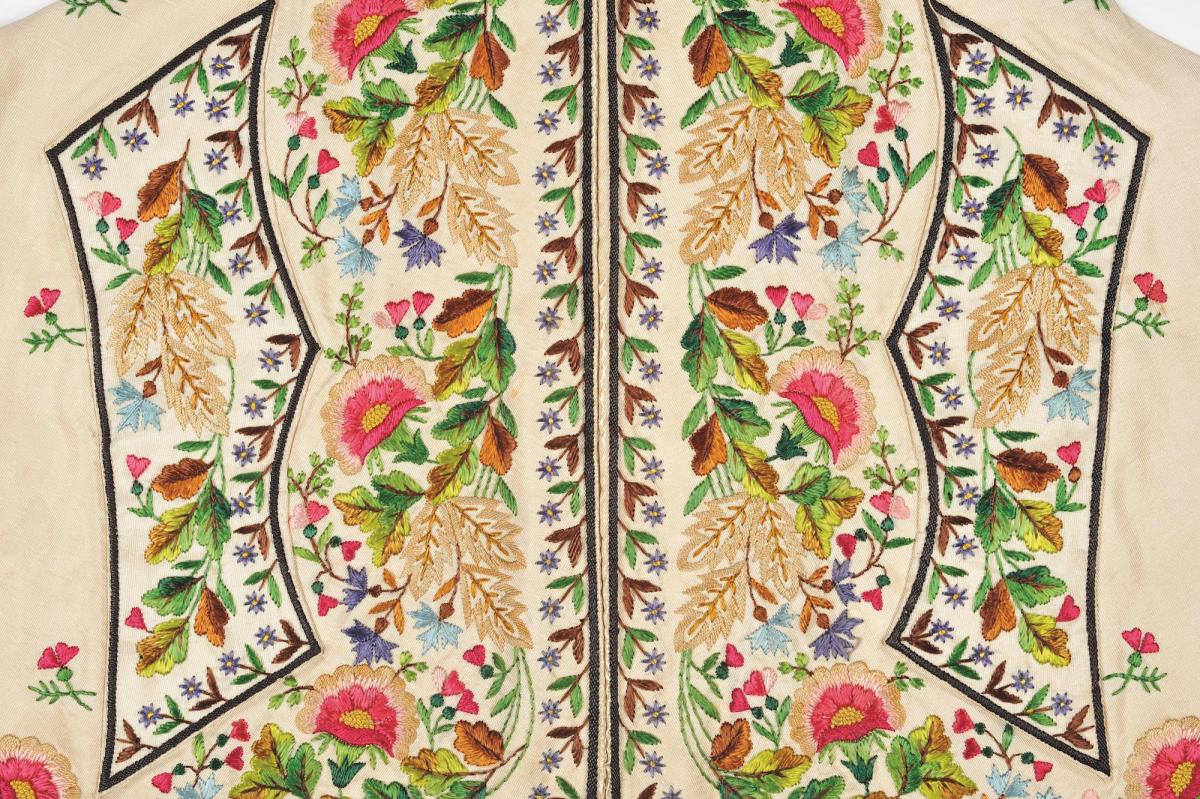

By the mid-century male and female dress was heavily embroidered; matching silk-shaded embroidery was now seen on gentlemen’s waistcoats, britches and jackets, so creating the three-piece suit – and for women, on adorned court mantuas. Continuing to slip between the professional and domestic, by the 19th century embroidery had returned to the home, with a favoured technique known as Berlin wool work. This was a durable canvaswork that needed only one type of stitch – the tent stitch.

Silk-shaded magnolias by RSN head of workroom Margaret Bartlett in the 1940s

By the 1870s serious embroiderers were concerned at the loss of embroidery skills across the UK. This led to the founding, in 1872, of the Royal School of Needlework (RSN). It had a twofold purpose of keeping the art of hand embroidery alive and of offering suitable occupation to educated women who, due to the loss of a husband or father, faced destitution. They were trained initially to create art embroidery, making pieces designed by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, Walter Crane and Gertrude Jekyll, among others. The first student, Martha Lee, was one of four daughters left unprovided for. She stayed with the RSN for nearly 20 years, before leaving to get married in New Zealand.

Embroidered detail of an 18th- century gentleman’s waistcoat

This year the RSN marks its 150th anniversary. Over 15 decades its embroiderers have worked on Queen Victoria’s funeral, all four coronations and many royal weddings. This century it has worked with fashion designers from Patrick Grant to Alexander McQueen and teaches hand embroidery to the highest technical and creative standards – the principal international prize for hand embroidery art, the Hand and Lock Prize, has been awarded to RSN graduates for four out of the last five years.

We view embroidery as an important art form today, but it has proved to be much more than that, especially during the pandemic. The medium has a particularly therapeutic element on the stitcher. Concentrating on stitch eases the mind and the body, allowing other parts to heal or relax. It is for this reason that the late Lady Anne Tree set up Fine Cell Work, introducing prisoners to stitch, and why many have taken to it in recent times, as an antidote to all that is happening externally.

SEE

150 Years of the Royal School of Needlework: Crown to Catwalk, Fashion and Textile Museum, London; 1 April–4 September; ftmlondon.org

May Morris and the Women’s Guild of Arts, an exhibition that focuses on May, daughter of William Morris and head of embroidery at Morris & Co; The William Morris Society, The Coach House, Kelmscott House, London; until 30 July; williammorrissociety.org

Platinum Jubilee: The Queen’s Coronation, Windsor Castle; 7 July–26 September; rct.uk

JOIN IN

To celebrate the RSN’s 150th anniversary, the school is offering a series of special online embroidery classes. Find out more at royal-needlework.org.uk

SPECIAL OFFER

The Creative Dimension Trust is offering Members of The Arts Society a 5% discount on its online and studio-based workshops. Experts will guide you in learning about

skills such as plaster carving and hand embroidery – the latter with Amy Burt, RSN tutor and haute couture embroiderer. All proceeds will go towards the trust’s charitable work in providing less advantaged students with workshop opportunities designed to encourage careers where fine hand skills are a prerequisite.

Just enter the code ‘ART5’ when booking at thecreativedimension.org/ adult-workshops

About the Author

Susan Kay-Williams

Susan is the chief executive of the Royal School of Needlework and curator of the 150 Years of the Royal School of Needlework: Crown to Catwalk exhibition. She is the author of An Unbroken Thread: Celebrating 150 years of the Royal School of Needlework, published this April by ACC Art Books. Among her Arts Society talks are Treasures of the Royal School of Needlework, Painting with

a needle: 18th-century embroidery for gentlemen and botanists and The stitching queens: embroidery in the Tudor period

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition