This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Sex, death and selfhood

Sex, death and selfhood

4 Jun 2018

Odd couple Egon Schiele and Francesca Woodman are brought together for Life in Motion at Tate Liverpool

He was the electric acolyte of Klimt, whose works quite literally lifted the skirts of the Austrian bourgeoisie. She took haunted pictures of women in empty rooms, surreal and blurred at the edges, like dreams. Both died extremely young, and both were fascinated by the dark side of the erotic.

For the first time, the work of figurative painter Egon Schiele and American photographer of the 1970s Francesca Woodman appears side by side, at Tate Liverpool.

As Life in Motion opens its doors, we talk to curator Marie Nipper about sex, death and selfhood.

Why this exhibition? Why now?

Ten years on from our Gustav Klimt exhibition, the gallery showcases the works of his protégé on the 100th anniversary of his death. His work is shown alongside that of Francesca Woodman, whose art has gained recognition since the 1980s for its innovative and expressive nature. The exhibition investigates their incredible ability to capture and suggest movement to create dynamic, extraordinary compositions.

Can you say a little about the title, Life in Motion?

Both Schiele and Woodman created intimate works that seem to capture moments in time, often depicting their subjects in the midst of a movement. Schiele’s drawings were made using quick, expressive, yet minimal lines depicting people in unusual poses showing the strain on the body. Woodman employed a long exposure to create blurred figures in her black-and-white photographs.

Rather than solely focusing on the physicality of their models and their own bodies in their self-portraits, both artists lay bare the psychological and emotional states of their subjects. We therefore look at motion not just as the physical movement of the body, but also in terms of psychological flux.

The work of both artists exhibits a raw sexuality. To what extent has that energy come to define the show?

Besides the obvious differences of one being a man and the other being a woman, and working in very different medias, they became known for their nude and psychological portraits and self-portraits. They both had the ability to capture, whether in drawing or photography, the physical tensions of the body and show it through an intimate and unapologetic work.

Due to the small size of both the drawings and the photographs, viewers will have a close and intimate encounter with the works.

Both artists are known for their self-portraits. How do their attitudes towards self-portraiture compare?

Both investigated and expressed personal selfhood from a very young age. Schiele was admitted to the Art Academy in Vienna when he was 16 and Woodman’s work with photography started at the age of just 13. Self-portraiture was often a matter of convenience for both. Schiele could not always afford models, and Woodman stated, ‘I’m always available’.

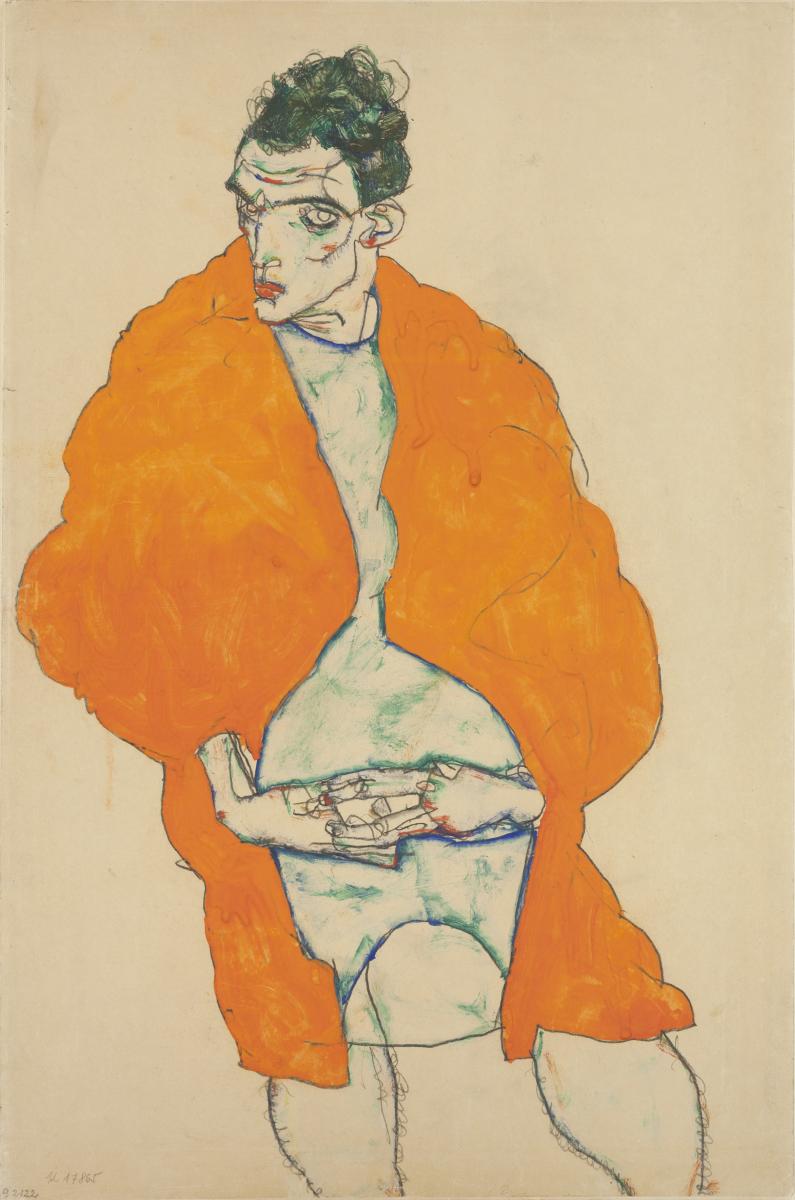

Throughout his career, Schiele would regularly return to self-portraiture, using it to explore various aspects of his identity as well as for formal experimentation. In his self-portraiture he plays with composition, sometimes cropping the figure and working with a spatial dislocation that makes the figure seem to dangle in space like a puppet on a string.

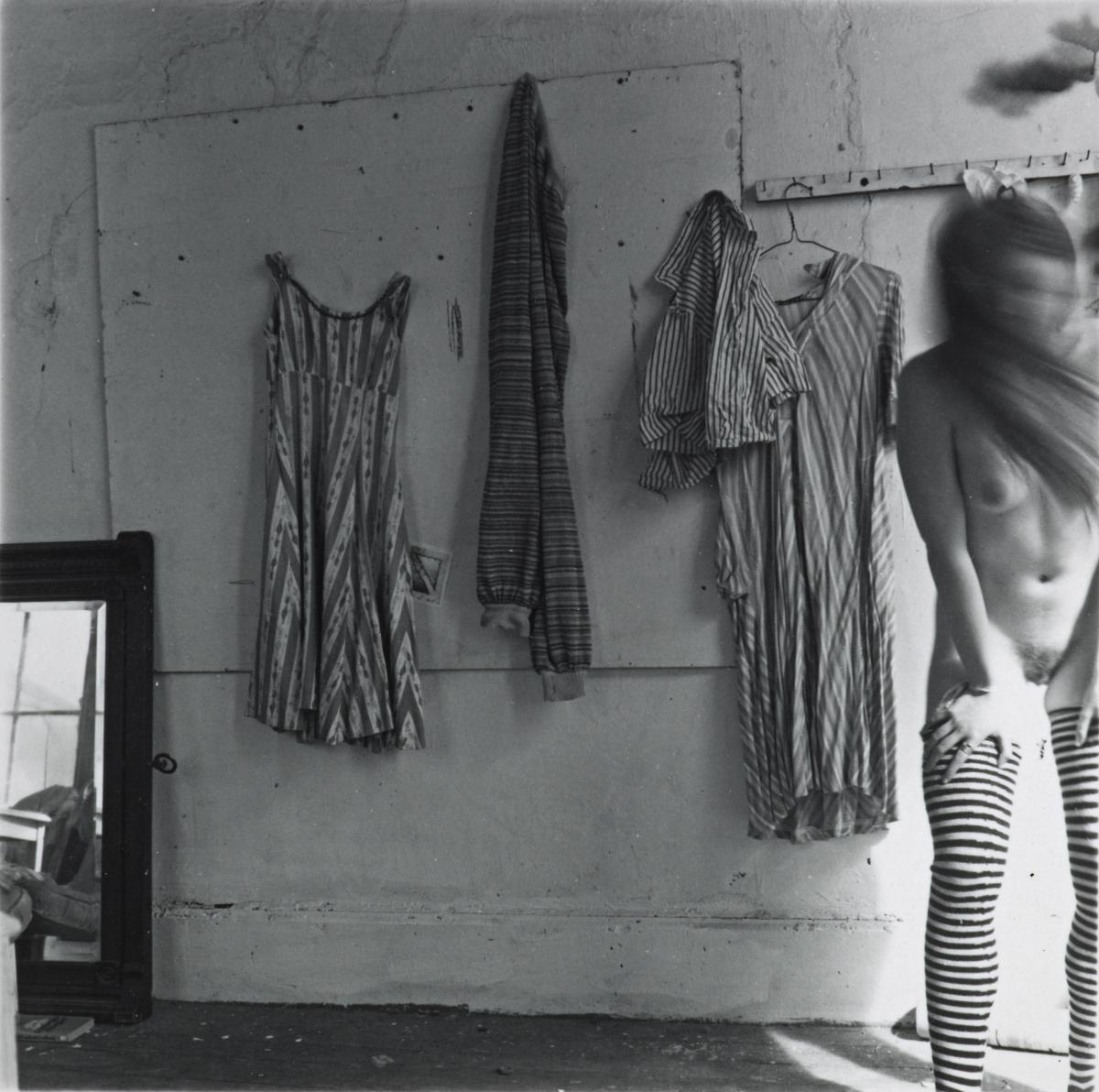

At the age of 13, Francesca Woodman took her first self-portrait. From the beginning, her body was both the subject and object in her work. Often nude except for individual body parts covered with props, sometimes wearing vintage clothing, she is typically sited in empty or sparsely furnished, dilapidated rooms, characterised by rough surfaces, shattered mirrors and old furniture. In some images, Woodman quite literally becomes one with her surroundings, with the contours of her form blurred by movement, or blending into the background, revealing the lack of distinction between figure and ground, self and world.

What is the most surprising aspect of this show?

Schiele and Woodman both created so much in such a short time, but the exhibition demonstrates that the appeal of their work goes way beyond biography and celebrates the creativity and productivity that was so expressively conveyed by both at a very young age. They found their own style and are remembered for it. I think that Woodman’s photographs help to refocus how we see the work of Schiele, highlighting how his practices and ideas have a continuing relevance to contemporary art.

What were the most important curatorial decisions for you in the making of this show?

We wanted to create an exhibition layout that gives the audience an understanding of the chronology in the artists’ work to show how style evolved over the span of their short careers. But we also want to demonstrate how both artists worked within a range of specific themes that ran through their entire practice, such as the body in motion and the self-portrait.

The works of both artists will be shown in alternating sections that are kept open for visitors to make visual connections between the works. While this is one exhibition that brings the work of these two artists together, we do not want to make it seem like their work is the same. An emphasis will be placed on their way of working and the subject matter addressed in the works, and through this, connections will become clear.

If you could take home one piece, which would it be and why?

Either Schiele’s Reclining woman with green shoes (1917) or Woodman’s Horizontale (1976). In Reclining woman… we see how Schiele, towards the end of his life, becomes increasingly naturalistic as he uses a greater economy of line, capturing his subjects in single, near perfect strokes. Throughout his career, he becomes a master of expressing the spirit of his subjects with an amazing economy of means. In his nudes, he strives for purity of forms, and with the precision of stop-action photography, Schiele – like no other artist – catches a moving body or the flicker of emotion. And because of this he ranks as one of the greatest draughtsmen of all times. I think this drawing remains as fresh and vital today as when it was made.

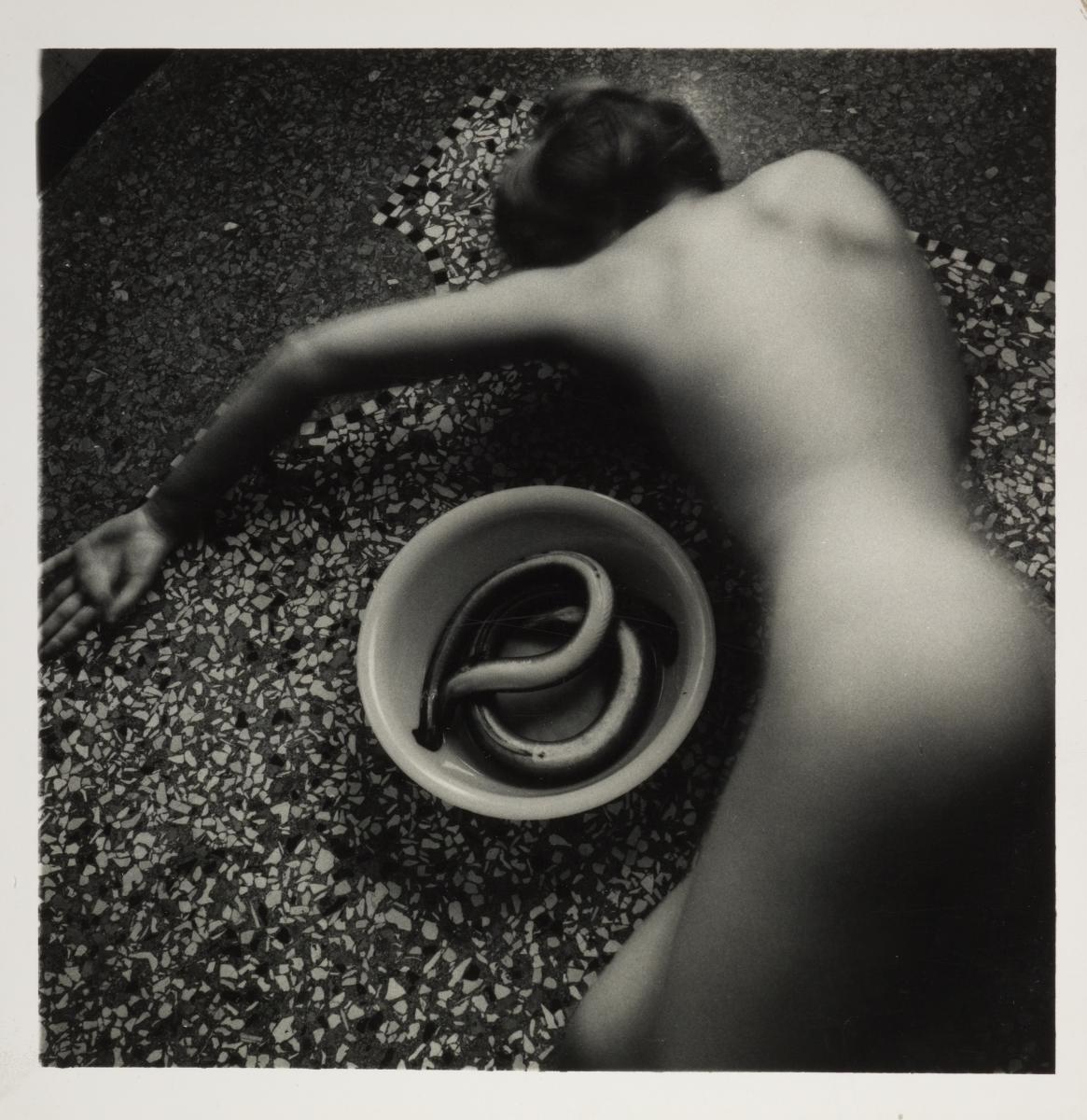

Horizontale shows a fetishist’s application of Sellotape to her own legs, which invites comparison to Surrealist photography. In Surrealist photography, however, it was typically men photographing women, whereas Woodman photographed herself. Many critics have therefore described her work as part of the feminist artistic movement of the 1970s that consciously rejected the dominating male gaze. But the truth is that Woodman probably wasn’t as interested in feminist issues as in exploring how emotions, and what she felt as an inner force, would be represented through art – in her case photography.

Would Schiele and Woodman have gotten along?

Well, that is a very hypothetical question, but I’m sure that they would have been able to have interesting conversations around the representation of the human figure in art and each other’s artistic search for capturing the body in motion.

Why should people see this show?

It is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see two iconic artists presented together and put in dialogue across time and space. They broke with tradition and tested their preferred media in different ways. Schiele pushed himself to capture the human body with both precision and speed in his drawings, and Woodman’s photography is a witness to her talent to investigate and express personal selfhood from the age of just 13.

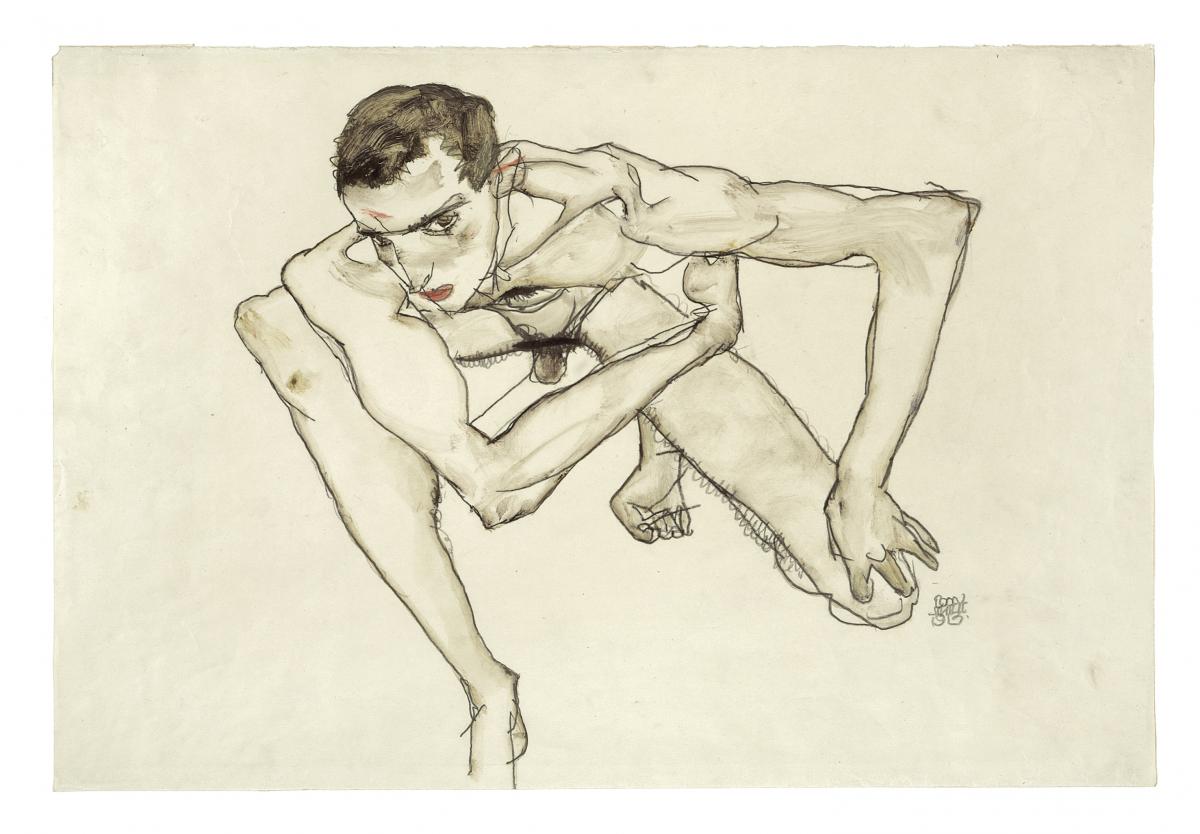

Images: Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait in Crouching Position 1913 Gouache and graphite on paper. Photo: Moderna Museet / Stockholm.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, Providence, Rhode Island 1976 © Courtesy of Charles Woodman/Estate of Francesca Woodman.

Egon Schiele, Standing Male Figure (Self-Portrait) 1914 Gouache and graphite on paper. Photograph © National Gallery in Prague 2017.

Francesca Woodman, Eel Series, Venice, Italy 1978 © Courtesy of Charles Woodman/Estate of Francesca Woodman

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition