This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Ravens, warriors and Goggle Heads: the new Elisabeth Frink exhibition, in the curator’s own words

Ravens, warriors and Goggle Heads: the new Elisabeth Frink exhibition, in the curator’s own words

27 Nov 2018

This winter, the Sainsbury Centre presents a giddying exhibition of work by post-war British sculptor Elisabeth Frink. With 130 works, it’s the largest display of her art in 25 years. Frink’s work is placed alongside that of figures such as Picasso, Giacometti, Rodin and Bacon.

One of the curators of the exhibition, Calvin Winner, picks five highlights.

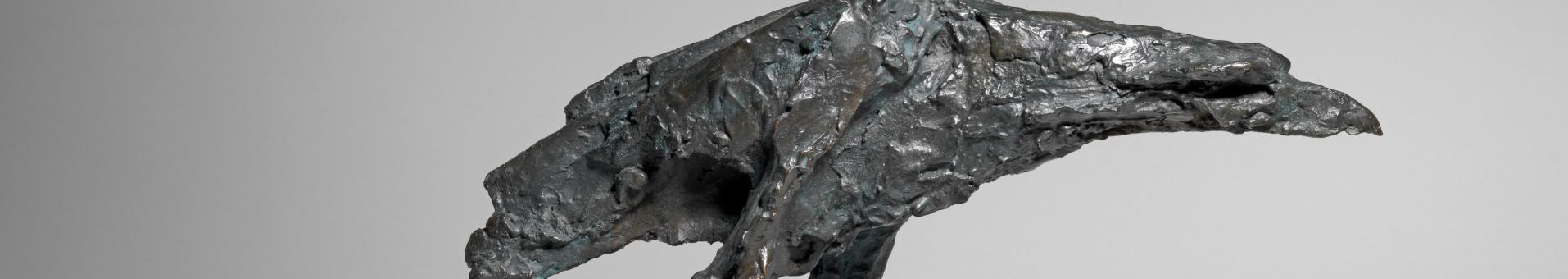

Bird, 1952

Elisabeth Frink (1930-93)

Bronze

This sculpture was made while Frink was still at Chelsea School of Art. It was included in her first show at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1952 and editions were bought by Tate, the Arts Council and the composer Benjamin Britten. Frink’s first decade was an intense response to the Cold War and ‘climate of fear’, producing a series of bird monsters full of foreboding as a metaphor for the shared sense of anxiety.

These expressionistic works developed into human-animal hybrids that mutate and metamorphose from more naturalistic forms based on corvids – ravens and crows – to forms more abstracted, expressive and militaristic. The bird metaphor allowed Frink to explore the theme in a haunting series of works with a truly gothic sensibility. These powerful bird avatars embody emotions and feelings that succinctly express the climate of fear that shadowed the post-war period.

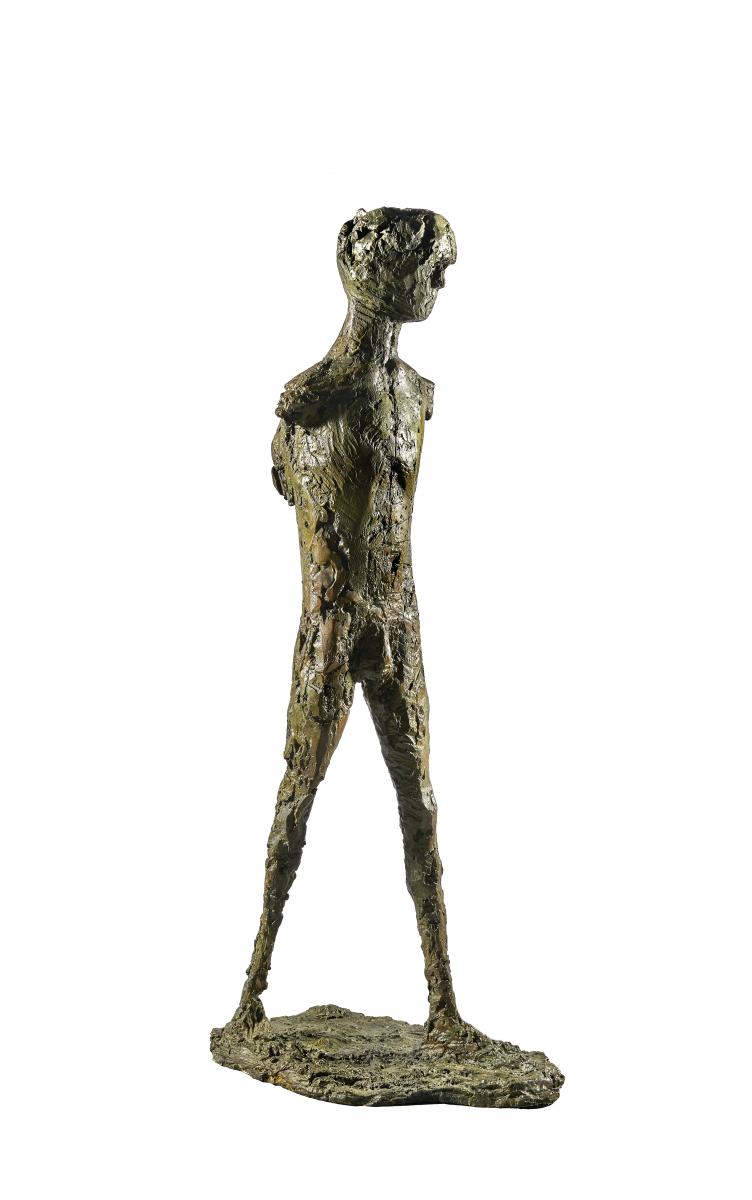

Birdman, 1959

Elisabeth Frink (1930-93)

Bronze

In the late 1950s Frink started work on a series of full-length figures such as Birdman (1959). In part, they were a continuation of the man-bird hybrids, but these works were inspired by her memories of World War II aviators returning from battle in damaged and broken aeroplanes to aerodromes near her childhood home. However, the spark was the self-styled ‘birdman’ Léo Valentin, a romantic adventurer who became an international celebrity for his heroic aeronautical feats, before tragically falling to his death in 1956. However, Frink’s sculpture is not altogether a victim, and tragedy is defeated by the heroic pose evoking that of an ascending angel. This spirit is shared in the response to Valentin by her friend, the artist César Baldaccini, which is also shown in the exhibition.

Goggle Head, 1969

Elisabeth Frink (1930-93)

Bronze

Frink’s most celebrated series is the Goggle Head sculptures, made between 1967 and 1969. Rather than portraits, they are anonymous symbols of brutality and agents of death. The goggles offered the avoidance of eye contact and a sinister edge – their eyes concealed behind polished headgear is a sign of malevolence. The undercurrent of kitsch in these grimacing faces only serves to heighten the uncomfortable spectacle. Frink indicated the image of the goggled face was impressed upon by reports in Paris Match of General Oufkir, a captain in the French army of Morocco, who allegedly arranged the ‘disappearance’ of left-wing politician Mehdi Ben Barka. More general sources of the Goggle Heads are gangland hoodlums, thugs, hired assassins or, alternatively, agents of state control or corrupt officialdom, such as formidable French police motorcyclists who caught her attention when she moved to France.

Riace IV, 1989

Elisabeth Frink (1930-93)

Bronze

The theme of the warrior was a vehicle for expressing a range of emotions, most notably the contrast of aggression and vulnerability, as well as her fascination with the male body; in particular, the contradictory forces of masculinity, power, strength and weakness that she explored in archetypal strong men, such as the Riace Warriors, made in the late 1980s – her fourth decade of work.

The Riace Warriors are all-powerful superhumans with their faces obscured to enhance the menacing effect. Frink described these threatening figures as very beautiful but also very sinister. They combine inherent raw strength with vulnerability, which we are reminded of by their nakedness. They were inspired by two 5th century BC Greek sculptures discovered in 1972 in the sea of Calabria, near Riace in Italy. Frink applied colour to their faces, possibly influenced by the knowledge that the Greek bronzes would have originally been coloured, but also by her recent encounter with Aboriginal art.

Frink Estate and Archive

Running Man, 1978

Elisabeth Frink (1930-93)

Bronze

Frink’s Running Man of 1978 is one of her most enduring creations. It is an image of humanity’s ability to strive against adversity, with stoicism and physiological strength. Vulnerable but also suggesting passive resistance, the Running Man related to her growing concern for human rights and support for Amnesty International. Whether these figures are running to or away from danger, they are symbols of hope and perseverance. The Running Man also defined her interest in masculinity. She was fascinated by the inherent physical strength and the sensual, sexual prowess of the male figure. She said: ‘I enjoy looking at the male body. This has always given me the impetus and the energy for a purely sensuous approach to sculptural form. I like to watch men walking and swimming and running and being.’

Calvin Winner is head of collections at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts

Elisabeth Frink: Humans and Other Animals is at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts until 24 February 2019

SIGN UP

For our free monthly newsletter, full of news, offers, and exhibition and book reviews: theartssociety.org/signup

DIP INTO

The Arts Society Magazine, out four times a year, which includes the latest in the arts world titles

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition