This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

My life in art: Arts Society Lecturer Linda Smith

My life in art: Arts Society Lecturer Linda Smith

5 Dec 2019

Linda Smith became an Arts Society Lecturer in 2005. She is a guide and lecturer at Tate Britain and Tate Modern, with a special interest in British art since 1550 and modern art. We speak to her about the joys of giving tours, the mastery of Lucian Freud and more.

How did you become an Arts Society Lecturer?

It was all a happy accident really. A friend heard me talking at the Tate and said I should be doing it for The Arts Society. I’m very glad I did, because I’ve had a lot of fun travelling around the different Societies and meeting so many lovely people.

You are an extremely experienced gallery guide. How did you first get into this line of work and what is it about the guiding format that you find interesting?

I first started taking gallery tours in about 2001. What I like about guiding is the directness of the relationship with the audience, who are just feet away, looking you straight in the eye rather than snoring away in a dark lecture theatre. You have to keep their interest, or they’ll just walk away. Every tour is different because every group is different. I learned how to speak off the cuff, cut out jargon and home in on the things people are likely to be interested in rather than waffling on about nerdy art-historical points. It helped me develop self-confidence, fluency and the ability to respond to unexpected questions.

One of your lectures is called The sublime to the ridiculous: Hogarth, Reynolds and Gillray. What unifies these three artists?

The sublime to the ridiculousis a three-part study day about three British artists whose careers spanned the eighteenth century. Their individual stories are very different, and each lecture stands very well on its own, but by putting them together in a study day it is possible to weave in the bigger subject of the changes in art in this country during that period, and how they interacted with society and politics.

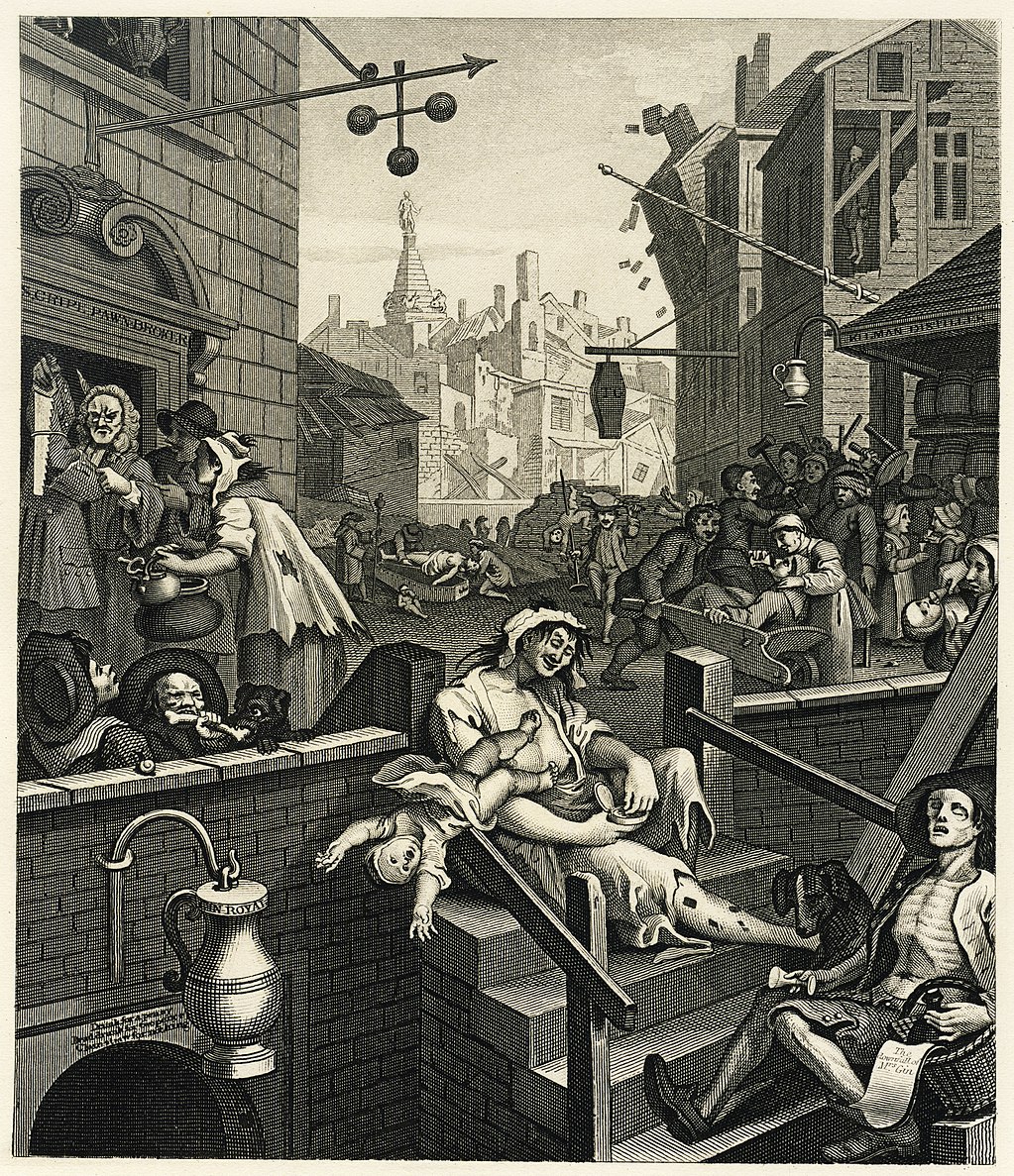

William Hogarth, Gin Lane, c1750

William Hogarth, Gin Lane, c1750

Hogarth, for example, is sometimes described as the founder of British art, because he is seen as having established a particularly ‘British’ style, and it is interesting to try and pin down what that might mean. Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, put in place a system which polished and professionalised British traditions, fusing them with European elegance and internationalism to produce something which certainly holds its own alongside European art, but which still retains a noticeable British quality.

Gillray, who was a caricaturist rather than a painter, had a very keen eye for pretentiousness and pomposity, in the art world as much as anywhere else. He brought outstanding craftmanship and draughtmanship to the long-established form of the satirical print, bringing it up to a level of scabrous brilliance which has pretty well set the standard ever since. Between them, they give us a nice snapshot of an important period in the development of British art.

Lucian Freud is the subject of a major exhibition at the Royal Academy right now, and his appeal seems stronger than ever. Considering your knowledge of British art, what do you think makes his work so compelling?

Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait), 1965 Oil on canvas, 91 x 91 cm Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

Reflection with Two Children (Self-portrait), 1965 Oil on canvas, 91 x 91 cm Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

Lucian Freud was one of several British artists who stuck with figurative art at a time when many people thought it was finished, and that abstraction was the only direction left for painting. Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and others showed that the age-old subject of the human body could still be pushed into new and intriguing territory. I think that the high esteem in which their work is held nowadays is a testament to this being one of the great strengths of British art in the postwar period.

As far as Freud is concerned, I think the appeal lies in the relentlessness of his gaze, and the way in which his sitters, even though ruthlessly exposed to us in every detail, always remain somehow distant and enigmatic. The physicality and texture of the paint fascinates people as well: in earlier works very precise, smooth and detailed, then later on sometimes fluid, applied in swooping strokes, sometimes claggy and gritty, as if laid on with a spade.

What makes a good lecture, in your opinion?

I really don’t know. You just have to smile, know your stuff and try not to be boring.

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition