This wonderful Cornish workshop and museum is dedicated to the legacy of studio pottery trailblazer Bernard Leach

Muse, conflict photographer and… celebrity chef: Lee Miller’s recipes

Muse, conflict photographer and… celebrity chef: Lee Miller’s recipes

25 Jun 2018

Lee Miller lived many lives.

The American artist was a fashion model; the protégé of Condé Nast. She was a muse to Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau, and an apprentice to Man Ray. She was a key Surrealist, as a new exhibition at The Hepworth Wakefield celebrates. As war correspondent for Vogue, she shot the Blitz, as well as the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau. After the liberation of these camps, she stripped and bathed in Hitler’s Munich bath. She left behind 60,000 staggeringly original photographs.

There is one feather In Miller’s cap, though, that has been wrongfully overlooked in recent years. After the trauma of the war, Miller put down her camera and reinvented herself yet again as an experimental chef. For the last 20 years of her life, Farley Farm – the East Sussex home she shared with her husband, Roland Penrose – was a Mecca for those interested in culinary artistry. Miller was a legendary hostess: everyone wanted an invitation to Farley, where she fed the likes of Picasso, Miró, Henry Moore and Max Ernst on cauliflower breasts, gold chicken and ‘Pink Heaven’.

Miller’s granddaughter, Ami Bouhassane, has lovingly compiled her grandmother’s inventions into Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends & Recipes.

As Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain opens at The Hepworth Wakefield, we sat down with Ami to discuss cooking as therapy, Hitler’s bath and goldfish for supper.

Image: Picnic, Ile St Marguerite, Cannes, France 1937 by Roland Penrose © Roland Penrose Estate, England 2018. The Penrose Collection. All rights reserved.

How did you come across the recipes in your book?

We always knew that my grandmother had written recipes; when she died she was well known as a gourmet cook and hostess with a difference. It was her photography that had been forgotten. As the Lee Miller Archives uncovered more of her photography and the world remembered her fashion, Surrealist and war photography, it forgot her as a cook.

What was your grandmother’s attitude towards cooking?

She never did anything by halves, she was completely gripped by cooking in every way possible: competitions, new and exotic ingredients, collecting recipe books (she left a collection of 2,000), trying all the new gadgets, a thirst to learn skills like butchering, making scrapbooks of ideas and recipe cuttings, creatively inventing recipes around certain foods… She enrolled herself on a six-month course in Paris in the Cordon Bleu school and also attended the one in London.

What can she teach us today about the art of entertaining?

From her art background she knew how to make a meal look exciting. But she also took a lot of care to think of the small details; things that would make the occasion really special for her guests. She would remember their food likes and dislikes, and have the lawn mown early in the week so the daisies would be out by the weekend for her visitors to enjoy. She was very skilled at keeping interesting conversation going around the table, and among her recipe cuttings in her scrapbooks are articles that could be used as talking points should the conversation dry up.

She often involved her guests in the preparation and presentation of a meal, rather than stressing over doing it all herself: they felt part of it, and it was more fun for all.

What were some of the dishes she prepared?

There was ‘Goldfish’ – a fresh-baked codfish covered in a carrot, onion and butter garnish to make it look golden. ‘Muddles Green Green Chicken’ is a happy accident of a dish that Lee invented by chance when trying to create a different dish. The green sauce is made from peas, two whole bunches of celery, fresh French parsley and leeks, and the dish was named after Muddles Green, the hamlet that Lee’s home is in.

‘Persian Carpet’ is a dessert made with sliced oranges, orange blossom water, crème de cassis and grenadine, and decorated with candied violets. Lee wrote on the bottom of the recipe: ‘I serve this on a silver platter which I pinched from Berchtesgarten – it has Hitler’s initials and an ugly eagle on it – no one notices.’

Image: Lee Miller’s food re-created © Levent Ultanur - silenzia.com / Courtesy leemiller.co.uk, England 2018

Would it have struck Lee that the kitchen was a more ‘traditional’ place for a woman than her work elsewhere as an artist, photographer and war correspondent?

I don’t think so. She would have been aware of it, but she was more into doing what she wanted to do. Above all, she cooked because it fascinated her – especially the science and invention side of things.

Do you think, having lived so many lives already, her reinvention of herself as a cook was a means of escaping the trauma of war?

Yes, but I don’t think it was conscious thing. I do believe that, post-war, she found going back to photography difficult. Maybe because after having experienced all she had, going back to shooting fashion and normal life seemed so flat, but maybe also because each time she used her camera, she was reminded of what she had seen through it. However, she was still a vibrantly creative woman – no longer able to use the camera all the time to release this, she found cooking the ideal outlet and escape.

Do you have a favourite Lee Miller photograph? What is it?

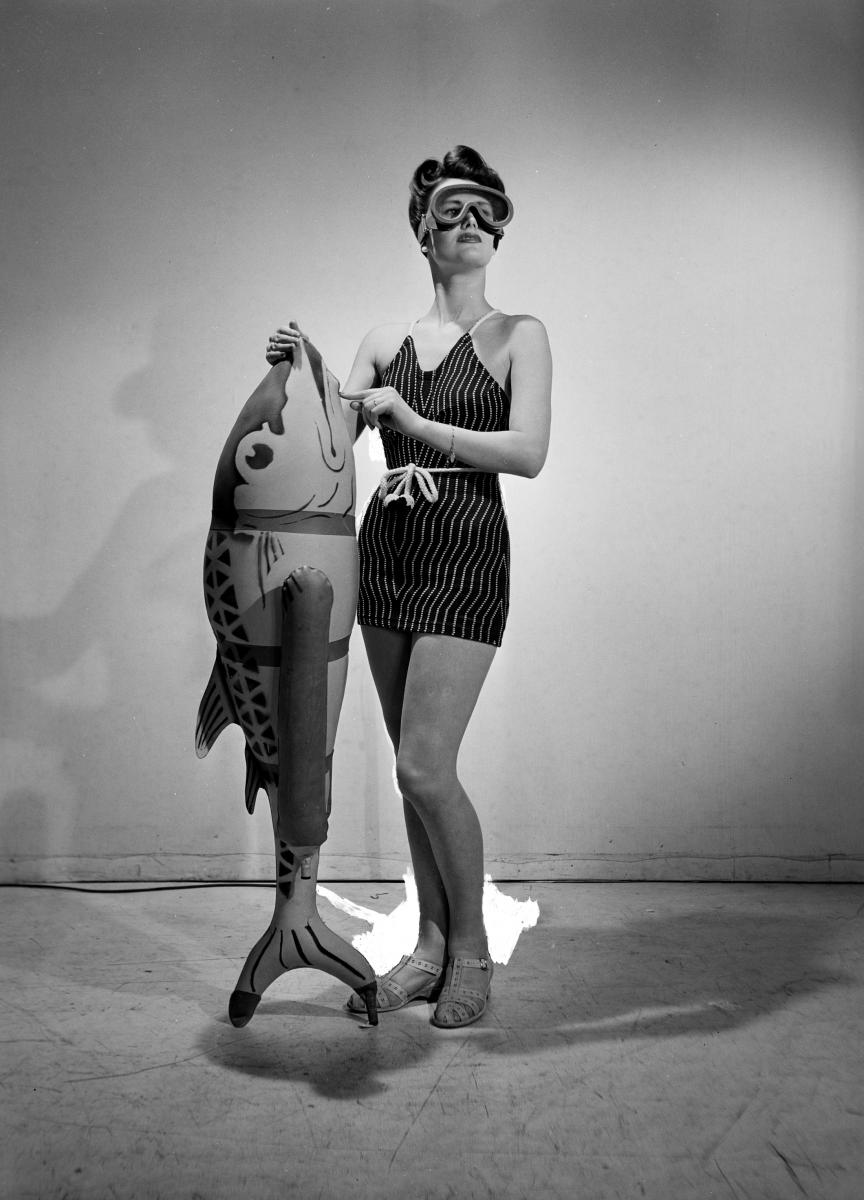

I have several, in fact the swimwear feature image that The Hepworth Wakefield has used as its poster image is one I’ve been fond of for a long time. As well as being great compositionally, I can see her playful sense of humour and personality through it. Alongside the very British fashion feel of the time that she captures, it’s also slightly surreal and nods towards our wartime stiff upper lip. Standing with perfect hair, large goggles and a giant fish is of course perfectly natural! There is a studio and technical aspect too. If you look behind the models calves you can see a white patch in the image too, that is where the stand used to keep the model still during the long exposure has been touched out of the negative.

Image: Lee Miller, Bathing Feature, Vogue studio, 1941, (c) Lee Miller Archives

What do you think compelled Lee to have her image taken in Hitler’s bath?

There is a mixture of circumstances: to start with she hadn’t had a bath for weeks.

She had also just come from witnessing the horrors of Dachau concentration camp at its liberation and found Hitler’s private space. A bathroom is a very personal space where we do things no one else might ever see. Unable to find him or fight him, she and David E Scherman, who was Jewish, chose to defile his private space by using it. Then, while doing this, they realised it was a scoop, so captured it on her camera.

She also photographed Scherman in the bath, but at a different angle, including the showerhead more centrally in the frame, in what is probably a reference to the showers used to gas prisoners in his camps.

What is a common misconception about your grandmother that you’d like to dispel?

That she died a worn-out alcoholic. People have forgotten that she was almost the equivalent of a celebrity cook when she died. They tend to ignore her as an artist and creator after childbirth, and think that she never learned to cope.

She did for a while use alcohol to try and escape the depression and trauma she experienced after the war, just as many others did that returned. But to me, her greatest personal achievement is that she found a way through. It was by no means easy, but she used her skills as a mistress of self-reinvention one last time to redirect her energy into cooking. When you have seen starved bodies, I can imagine that sharing good food with those dear to you who have also survived meant a lot more. Whether intentional or not, cooking, as she said herself in an interview, ‘is therapy’.

What do you think Lee would object to about the times we live in today? What would she be most pleased about?

I think she would strongly object to the conflict in places like Syria, and the politicians’ inability to resolve it, but above all the suffering of innocent people. She had a very strong sense of truth and justice.

She’d probably be most pleased with the advances in technology. She had quite a technical and scientific mind and totally loved new gadgets!

Lee Miller: A Life with Food, Friends & Recipes, Ami Bouhassane (Grapefrukt Forlag)

Lee Miller and Surrealism in Britain is at The Hepworth Wakefield from 22 June–7 October; hepworthwakefield.org

About the Author

The Arts Society

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Become an instant expert!

Find out more about the arts by becoming a Supporter of The Arts Society.

For just £20 a year you will receive invitations to exclusive member events and courses, special offers and concessions, our regular newsletter and our beautiful arts magazine, full of news, views, events and artist profiles.

FIND YOUR NEAREST SOCIETY

MORE FEATURES

Ever wanted to write a crime novel? As Britain’s annual crime writing festival opens, we uncover some top leads

It’s just 10 days until the Summer Olympic Games open in Paris. To mark the moment, Simon Inglis reveals how art and design play a key part in this, the world’s most spectacular multi-sport competition